How They Made It: The Haircut Scene in ‘The Bourne Identity’

Matt Damon, Franka Potente, an awkward director, some shears, and a bottle of Jagermeister came together in 2002 to create one of the most surprisingly sexy scenes to ever appear in an action movie2020’s summer blockbuster season has been put on hold because of the pandemic, but that doesn’t mean we can’t celebrate the movies from the past that we flocked out of the sun and into air conditioning for. Welcome to The Ringer’s Return to Summer Blockbuster Season, where we’ll feature different summer classics each week.

Halfway into the filming of The Bourne Identity, Doug Liman was a nervous wreck. The director had been anxiously eyeing a pivotal romantic encounter between his movie’s two stars, Matt Damon and Franka Potente, which would cap the production’s time in Paris ahead of Christmas vacation. As the day of the scene approached, a dark cloud loomed over him. “I was like, In three days we’re shooting the sex scene, in two days we’re shooting the sex scene …” he says. “I was terrified, truly terrified. There was nothing else in the film that scared me like that.”

In reality, Liman had planned to shoot only a brief makeout session, but that was still enough to spook him. With only three movies on his résumé, he had never filmed something so passionate. Plus, the love connection between Jason Bourne and Marie Kreutz was a focal point of the screenplay. He knew he couldn’t back out. “It’s just awkward. I mean, I’m sure plenty of filmmakers are like, ‘There’s nothing awkward about it at all,’” he says. “It’s easier said than done, at least for me.”

This temporary panic had been a long time coming. When Liman first pitched Universal Pictures with his vision for adapting Robert Ludlum’s series about an amnesiac assassin, he leaned on his personal experiences living in Los Angeles with a female roommate. He wondered what might happen if a regular woman randomly met a cowboy action figure like Jason Bourne, who struggled with loads of dark, murderous baggage. “Anyone else who had the rights to this book would be telling you, ‘Imagine if you were Jason Bourne,’” he told the studio. “My take on this is, imagine if you were dating Jason Bourne.” That unique dynamic between Marie and Jason—actualized by screenwriter Tony Gilroy—was essential to the movie’s effectiveness. And the scene that Liman had feared was essential to nailing the dynamic.

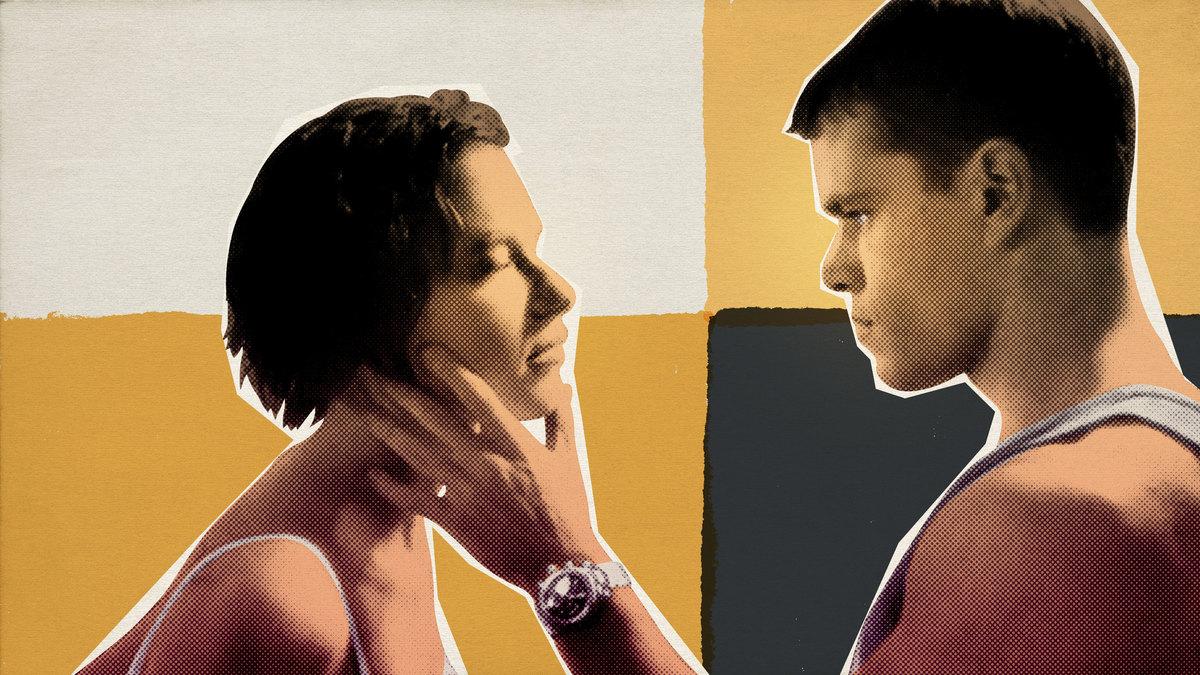

It occurs midway through the film, following a climactic car chase in which Bourne and Marie elude fleets of police in Paris. With their covers blown, the couple checks into a rundown motel, and to avoid authorities, Bourne changes Marie’s appearance, carefully dyeing and cutting her hair—a deeply intimate act that eventually evolves into actual physical intimacy. The crucial scene lasts just two and a half minutes and has zero dialogue. It’s tender, quiet, and sexy, developing both character and plot, and concludes as the camera gradually floats out the door, down the hall, and into the street.

In a larger context, the scene is the culmination of the characters’ time—and actors’ chemistry—together, elevating what could have been a generic, hypermasculine spy thriller into a deeply human, realist, and modern classic. The movie, which debuted on June 14, 2002, made more than triple its budget, earning $214 million, and laid the foundation for numerous genre-changing sequels. That scene in a rundown bathroom of a Parisian motel is a microcosm of its success. But getting there required tons of rewrites and reshoots, perceptive details, and a little liquid courage.

Despite his indie beginnings, Liman had always wanted to make “a big dumb action movie.” He’d grown up on Steven Spielberg and American blockbusters; he didn’t have a cinephilic upbringing admiring French New Wave like Quentin Tarantino. “I was not interested in high art. I was interested in mass entertainment,” he says. Swingers, and to a certain extent his 1999 follow-up, Go, were “résumé pieces,” character studies that would allow him to eventually engage in full-throttle action.

The Bourne Identity was his opportunity. The story centers on a man, Jason Bourne, with extreme memory loss, trying to uncover his previous life as a CIA operative in a clandestine and conspiratorial department. In the search for his identity, Bourne meets Marie, who is willing to help him in spite of his surprisingly violent background and lethal skills. Set primarily in France, Bourne was the perfect international playground for Liman to flex his mainstream muscles. “I realized in the first seconds of when I finally sold it that I was way more interested in character than I ever thought I had been,” Liman says.

He’d earned the rights to the film years earlier thanks to a dramatic pitch to Robert Ludlum. Inspired after reading Bourne, Liman, who had just earned his pilot’s license, took his “shitty little plane” to Ludlum’s home in Glacier National Park, surviving a dangerous flight over the Tetons that prompted Ludlum to call in the National Guard because of the filmmaker’s tardiness. The author was impressed with Liman’s house call, and allowed him to shop his material around. When Universal purchased the project, executive producer Allison Shearmur joined to guide Liman through the process of fulfilling his personal angle.

Though Liman considered casting Timothy Olyphant (after their time together on Go) to play his hero, Shearmur warned that his leading man should have more recognition. They pivoted to Brad Pitt, but when he dropped out, Damon quickly leaped at the role—coming off All the Pretty Horses and The Legend of Bagger Vance, he was eager to attach himself to a potential blockbuster that could further elevate his young career. As for Bourne’s love interest, Liman always hoped Potente would play the part. He’d been captivated by her red-haired, manic presence in Run Lola Run, and felt the German actress would be ideal for an overseas thriller. Conditioned by his independent studio upbringing, Liman wasn’t used to having carte blanche during casting, and still assumed he would have to settle for another actress. “And then my casting director is like, what about casting Franka Potente?” Liman says. “I’m like, ‘I can do that?’” Even though the initial chemistry reads between Potente and Damon didn’t jump at him, Liman remained confident he’d found the right pair. “It was obvious that she was going to be amazing in the role,” he says. (Through representatives, Damon and Potente declined to be interviewed for this article.)

The script wasn’t as obvious. Liman hired W. Blake Herron to craft a blueprint of the story, while he and Shearmur brainstormed detailed plot ideas in his New York apartment. Liman remembers one eureka moment that seems silly in hindsight. Trying to figure out the movie’s love story, he’d thought about inserting an epic car chase in the middle of the movie, “and then their adrenaline can be all revved up and they go have sex,” he exclaims. Shearmur thought it was a brilliant way to mesh the characters together. “We were like, ‘Oh my god, we’re revolutionizing filmmaking.’” Here, he takes a brief pause, and then adds: “Obviously what I just described is as clichéd and banal as it gets.”

In clear need of a polished writer, they targeted Gilroy, who was skeptical at best when approached by Liman. “Those works were never meant to be filmed,” he told The New Yorker in 2008. “They weren’t about human behavior. They were about running to airports.” Liman and Universal executives hounded him to take the job until he finally accepted; writing to Damon before filming began, Gilroy explained that Bourne’s DNA was “action with intimacy. Emotional credibility. Exotic locations treated in a completely nonglamorous way. Molecularly real people thrust into a heightened realm.”

As he parsed the new script, Liman realized Gilroy had unlocked the romantic arc of the movie, just as he’d hoped. Early on, when Marie initially pulls up to Bourne’s apartment in Paris, helping him to avoid Swiss police in exchange for $20,000, he invites her up to explore his unfamiliar home.

“You would probably just forget about me if I stayed,” she tells him.

“How could I forget about you?” Bourne replies. “You’re the only person I know.”

“That was the whole building block from that love story, when Tony came up with that line,” Liman says. Gilroy also kept the car chase that placed them together, leading to the couple’s motel tryst. But even with the dynamics set and squared away on paper, the job was only half-done. “It’s a whole other thing when you get ready to shoot it,” says Liman.

By the time Bourne and Marie reach the motel, they’re desperate. Having just survived an assassination attempt from a hired gun, and then outmaneuvering law enforcement in a nausea-inducing Mini Cooper ride, the pair sheds their belongings and prepares for a night together before going off the grid. For the first time, the movie slows down, and the actors—without speaking to each other—catch their breath. But the night they began shooting, both Liman and Damon were sweating with anxiety.

Noticing the pair’s nerves that week, Potente brought a bottle of Jägermeister to set. “She turned to Matt and me and she says, ‘You each need to do a couple of shots to just loosen the fuck up.’ It was the only time I’ve ever drunk on set,” Liman admits. “And I’m operating the camera—like, it could go south pretty quickly.”

The scene begins at the bathtub. In the book, Bourne avoids recognition by dyeing his hair blond and fastening some tortoise-shelled glasses to his face, while Marie goes without makeup and pulls her hair back. The movie’s hairdresser, Kay Georgiou, knew that wouldn’t work with the movie’s shooting schedule and Damon’s crew cut, which made using any kind of wig impractical. Marie needed to change her hair instead, especially considering her more distinctive red and yellow streaks. Though going full blond seemed like a logical choice, Shearmur rejected the idea. “I remember looking at Allie and thinking, ‘Oh thank god you said that,’” Georgiou says. “Women spend hours upon hours in a salon getting their hair dyed blond. Somebody who was previously a hit man is not going to have the knowledge of [dyeing] someone’s hair blond.” As an alternative, they decided on a believable dark brown.

Before things intensify, Bourne holds Marie’s head under the faucet, tenderly washing in the dye and then cutting her hair into a choppy bob. Potente had worn a longer wig up until that point, so Georgiou added some extensions to her shorter, natural hair for Damon to shear. “Every time he cut her hair, I would have to take her away, take out the old extensions and put in the new extensions,” Georgiou says. “They were fairly quick to turn around. … It’s not the most beautiful haircut in the world, but it shouldn’t be.” Potente later told Esquire she wasn’t exactly confident in Damon’s abilities: “He cut the extensions. But still, it’s kinda like, You know, do a good job.”

“We got a kick out of the fact that, you know, in the next scene, when her hair comes out, it looks really kind of contemporary and great,” Damon told ABC during the press run for the movie. “People have been asking if I’ll cut their hair and I’m telling them, ‘You don’t want me to go anywhere near your hair.’”

Because of the dingy nature of the bathroom, cinematographer Oliver Wood didn’t need to rig anything special for the lighting. He set up Kino Flos, portable LED-based lights, for the small interior scenes, which in this case were shot in a warehouse. “Doug didn’t want it to look conventional ever,” he says. “Bourne was a very natural movie anyway.” Wood shared camera-operating duties with Liman, and the pair often shot scenes with two cameras at the same time. Inside the cramped bathroom, they simplified things by capturing the scene once from two different angles. “I was used to getting things in one or two takes,” Liman says. “Having just the camera on my shoulder, I just stepped to the other side of the bathroom to shoot.

“That’s the thing about working with young beautiful actors,” he adds. “You can get away with gritty, real lighting.”

Once Bourne finishes styling Marie’s hair, he cleans up her locks and moves toward the sink, trying to squeeze around her body. Marie, however, blocks his path, waiting for him to acknowledge her. Bourne has been so regimented and brainwashed that it takes a few beats for him to recognize what’s happening. The scene pivots from awkward to intimate, a transition that rests solely on Damon and Potente. For Liman, the moment reflected his own lack of romantic awareness.

“If he had been James Bond and I was directing that scene, it probably would have looked the same, and people would have been like, Why is James Bond looking so reticent?” he says. “What you’re seeing is my awkwardness … they sort of look at each other in the eyes and start kissing. I don’t know what that look is because maybe I’ve never experienced it. … He’s trying to get past her. He’s trying to get out of the scene the same way [I am].” Though Potente was the driving force, Liman was keen on seeing something click in Damon’s eyes, and occasionally talked them through the shot from behind the camera. “[Bourne] was a very vulnerable human being,” Wood says. “When you see him looking into her eyes, you can tell that he’s going, ‘What’s this feeling? I’ve never felt this before.’”

Filming the scene went rather quickly. “I did two takes, one from one side of the bathroom, and one from the other side, and that’s all I had. When we got to editing it was like, ‘Holy shit, we barely got away with this,’” Liman says. But that also meant that the movie’s editor, Saar Klein, hardly needed to play around with the coverage. “I know people think the Bourne franchise is really cutty, but it was really thoughtful about when to do it,” he says. “A scene like that, the emphasis is just not to overdo it and just let the chemistry and the acting be in the forefront.” For the length of the project, Klein recalls trying to maintain a rough-edged quality to the film, and the bathroom scene exemplified that aesthetic. “We were just on the same page,” he says of Liman. “We’re coming from the same place, from an independent kind of world.”

Perhaps an extension of his prudish sensibilities, Liman doesn’t hold on the scene very long. Eventually, the camera drifts out of the bathroom, then out of the hotel, a decrescendo that cuts to an aerial shot of Paris. The next morning, Marie wakes up in bed and greets Bourne, who sits dressed ready to leave the city. “You can feel me running for the hills,” Liman jokes. “I made myself vulnerable and I’m done.”

Still, it works. The actors’ chemistry, built over the previous month of shooting, had paid off in a mesmerizing way, and the stress Liman felt is hardly recognizable in the finished product. “What strikes me is the giant gulf between the emotions I was feeling while I was shooting it and what it looks like,” he says. Georgiou, though, does have one sour taste from the experience that still lingers.

“I think that was the first time I’ve ever had Jägermeister,” she says. “And probably the last.”

Unlike the intimate brevity of that scene and its one-night production, the rest of the movie was a chaotic ordeal. As has been well documented, Universal felt Liman’s methods were costly and unorganized, a product of the filmmaker’s instinctual nature. “You learn about their personality and their decision-making process,” says Klein, who eventually developed a shorthand with his director. “It’s a little more all over the place.” In one instance, Liman realized he needed to redo a short scene in the countryside, but the studio told him it was too late. He took his camera and shot it anyway. “He didn’t care about the conventions or budgets, all he cared about was shooting the movie and getting what he wanted,” Wood says.

After more reshoots and production disputes, Universal showed a rough cut to test audiences and felt the movie needed bigger action beats for the finale. With the production well behind schedule, a different cinematographer helped shoot an ending that sees Bourne use a dead body to catch his fall from several floors up. “When he did that, it was like, ‘What’s this guy, Superman?’” Wood says. “The whole point was that he wasn’t that.” The movie’s release moved from its original slot in September 2001 to the following February, and then to June. “I never felt like I was going to lose control,” Liman says. “I was worried it wasn’t going to be good.”

Of course, Liman’s doubts turned out to be unfounded. Despite the numerous delays, The Bourne Identity earned critical acclaim and was a hit with audiences. It put Damon’s career on an ascendant trajectory and redefined the action thriller with its filmmaking choices and portrayal of a vulnerable leading man. Maybe most importantly, it made Marie more than a disposable female sidekick. “She’s up against a very compelling character and could have been arm candy, and she is not,” Liman says. Klein agrees, still impressed with the way Potente handled herself in her first American movie, and a big one at that. “I think if that relationship didn’t work, then the film would have fallen apart. It would have been just an action film,” he says.

Reflecting on one of the more stressful nights of his film career, Liman says neither he nor Damon wanted to admit their emotions to the crew or cast during that final week of shooting in Paris. Luckily, he had Potente, who helped take the reins that night, eased her costar and crew through the scene, and legitimized the movie’s point of view.

“I’m really happy with how it turned out. … It doesn’t overstay its welcome, it’s not gratuitous. It feels really raw and honest,” says Liman. “Every once in a while, I’m like, ‘I can’t believe I did that.’”

Jake Kring-Schreifels is a sports and entertainment writer based in New York. His work has also appeared in Esquire.com, GQ.com, and The New York Times.