“Everyone Is So Afraid”: COVID-19’s Impact on the American Restaurant Industry

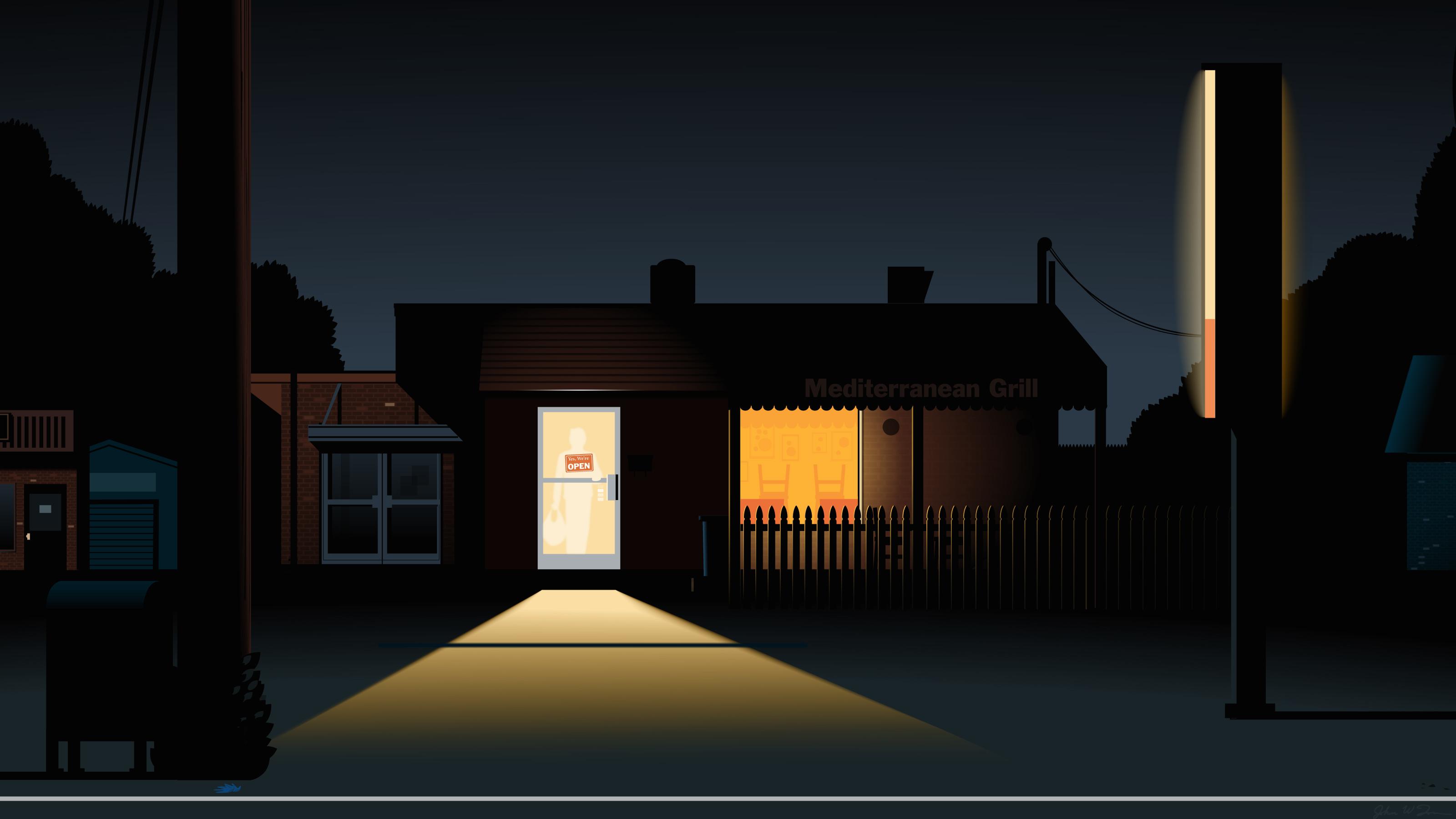

For Café Rakka in Tennessee and its fellow restaurants nationwide, the coronavirus pandemic has become a crisis unlike any in living memory. With tolls both human and financial, there’s no guidebook for how to move forward.Here’s one story from one restaurant in a nation of more than a million, at a time when all have been wracked with the same panic and weighted by the same fears. On the night of March 28, about half of the 18 employees at Café Rakka, a Syrian restaurant in Hendersonville, Tennessee, stood together in the kitchen. They wore aprons over their bodies and masks over their faces, and they gathered around their boss, the chef and owner, Riyad Alkasem.

“So,” he asked them, “what do you guys want to do?”

He’d been asking the rest of the staff that question all day. Riyad was trying to make the same decision that every owner of every restaurant, in America and many other parts of the world, has faced over the past few weeks. “Should we close?” Conventional wisdom seemed to shift daily. So did his gut. He didn’t know what was best—for himself or his business, for his employees or their families.

The coronavirus had taken hold in every corner of the country. The results, for restaurants, had been catastrophic. A few miles away in Nashville and in other corners of America, some restaurants had closed weeks earlier, in mid-March. Others had tried transitioning to takeout, only to shutter within days or weeks. Others still were pushing forward with services like Postmates and Grubhub, hoping delivery could keep them afloat. Here in Tennessee, the governor had not yet issued a stay-at-home order. Even when that order arrived on April 2, restaurants would still be allowed to serve meals to go. They would still have a decision to make.

Riyad looked around the room, gauging the mood. This restaurant was his life’s work. He’d learned to cook these meals in his grandmothers’ kitchens and in the “tribe houses” of his hometown in Raqqa, Syria. Now his grandmothers were dead, his native city destroyed by war. But his restaurant still stood, and with it a piece of his tribe’s culture, finding new life thousands of miles away in a Tennessee strip mall. But with the virus in the air, business was eroding. The restaurant was bringing in 23 percent of projected weekly revenue. “The ship was sinking slowly,” he would tell me later. “We were choking. Going underwater.”

That night, he looked around at his employees. They ranged in age from their early 20s to their 50s. A few were white, native Hendersonvillians. Others were immigrants from Jordan and Ecuador and Mexico and elsewhere. “This is my new tribe,” he likes to say about himself and his staff. Together, they’d built a restaurant consistently named the best in their mostly white and conservative suburban county. But now, he looked around the room and he saw that they were afraid. Of illness. Of unemployment. Of how the virus could destroy life in so many cruel and unpredictable ways.

“If you are open, I am here,” said Mohammad Khader, his second sous chef.

“If we sit at home,” asked prep cook Rafa Lima, “what are we gonna do?”

Riyad knew what that meant. He didn’t wonder what they’d do out of boredom. He wondered what they’d do to make the money needed to survive.

They talked it over for a while, weighing terrible options. The virus seemed like one kind of killer, unemployment and poverty like another. Congress had just passed the CARES Act a couple of days before, intended to help workers and small businesses through the crisis, but it was still unclear how much, if at all, that would help. If they shut down and aid proved limited, Riyad might be able to give the neediest employees money from his own pocket, but not much. His restaurant is small. Like most, its profit margins are razor-thin. At home, Riyad knew his wife and two sons were terrified for his safety. Riyad is only 52, but he’s dealt with heart problems over the years. His sons are both immunocompromised. His family wondered whether he should protect himself by isolating at home. Either choice, open or close, seemed to carry its own grave risks.

Finally, they reached a decision. They would stay open for delivery and curbside pickup. The next day, they’d make that decision again. Deciding their fate daily would become their new normal. On the day this story is published, Café Rakka remains operational. Tomorrow, it may well be closed. All across the country, restaurants are shutting down. Some may never reopen. And what’s at stake, for our economy and our culture and for the lives of those who own and staff them, is far greater than just a matter of a few businesses closing their doors.

“No one has ever done this before and written a guidebook saying, ‘Look, here’s how you do it,’” Riyad says.

“It’s absolutely impossible to know what to do.”

I’ve spent the past few weeks talking with Riyad almost daily. He is my friend, the subject of an upcoming book I’ve written about him and his brother and their journeys out of Syria. (He’s also the subject of a story I wrote for The Ringer about his experience with Donald Trump’s election in 2016.) For the past few years, we’ve talked for hundreds of hours late at night, in the storage room behind his kitchen. Lately, we’ve been talking by phone, and a couple of times in person, very briefly and from a distance, when I’ve driven up to get curbside takeout orders of hummus and lamb. Some days, he’s been optimistic. “I’ve been through a lot of calamities,” he said one night, remembering his journey out of Syria as a young man, and his journey back to try to save his family at the height of his country’s civil war. “Every calamity I face, it always looks dark, but there’s a bright side you have to look for. No matter what, I can never let anything stop me.” Other days, he’s sounded somber. “Our industry,” he said one afternoon, “is changed forever. Or if not forever, then for a very, very long time.”

Riyad is one restaurant owner in one pocket of the country. His current struggle, though, is shared by all. (Well, almost all. Domino’s and other pizza delivery chains are thriving.) So while following his journey through these weeks, I also reached out to chefs and workers and others connected to the industry, trying to understand all that is at risk of being lost. Some of those conversations turned to business. (“There’s a massive solvency cliff here,” says Camilla Marcus, chef and owner at West-Bourne in New York.) Others turned to labor. (“We desperately need protections for service workers on the front lines,” says Drew Herrmann, a labor lawyer in Texas.) Some of the stakes feel personal. (“My identity is wrapped up in taking care of people who work for us,” says Andrew Hoffman, owner of Comal in Berkeley, California. “It’s hard to grapple with that loss.”) And some feel cultural. (“In this restaurant,” says Riyad, “my heritage is alive.”)

No one has ever done this before and written a guidebook saying, ‘Look, here’s how you do it. It’s absolutely impossible to know what to do.Riyad Alkasem, Café Rakka

All of this adds up to a crisis unlike any in the living memory of the restaurant business, wrapped up inside a crisis unlike any in the living memory of much of the world. “If we had aliens come to the world,” said Dave Chang, the chef and founder of Momofuku, on his recent Ringer podcast, where he’s lately been interviewing chefs about the ongoing crisis, “and the only thing they wanted to do was destroy restaurants, that’s how we should imagine this.”

Since closing West-Bourne on March 15, Marcus has thrown herself into advocacy efforts. She’s a founding member of the Independent Restaurant Coalition, a group of restaurant owners that began organizing last month to advocate on their industry’s behalf. Together, they’ve been working to make sure that independently owned restaurants have the voice in Washington that they’ve long lacked. “We are collectively among the largest employers across the nation,” she says. “And we have not had a seat at the table.” Independent restaurants employ 11 million people, according to the Independent Restaurant Coalition, contributing $1 trillion to the economy and representing 4 percent of GDP.

“Everyone knows independent restaurants are important,” says Marcus, who holds both a law degree and an MBA from NYU. “Yes, we are critical to the fabric of communities—we are anchors, we are lighthouses. All of that is true. But from an economic standpoint, we’re even more powerful.” Restaurants, she says, are among the few industries that can offer anyone a ticket to the middle class. “What other industry offers zero barrier to entry, with long-term career prospects?” she asks. “Very few industries can promise a real middle class to our country. Restaurants can.”

Marcus points to a meeting about responses to the crisis held last month between President Trump and CEOs of several restaurant chains, including Domino’s and Chick-fil-A, and to the special funds earmarked for airlines and cruise companies. “Compare us to the big chains, and to the airlines and cruise companies that are being bailed out,” she says. “There’s fewer of them. But they’ve had intense lobbying power for decades. We’re playing catch-up.” She’s careful to stress that she doesn’t see herself and her colleagues as in competition with those companies. “We’re not saying it’s us or them. We’re saying us and them.”

“This restaurant,” Riyad says, “is my calling.”

Technically, he opened Café Rakka in 2007. But as with so many other restaurants in so many corners of the world, the seeds were planted decades earlier, the restaurant the culmination of a journey Riyad began when he was a boy. Growing up in Raqqa, on the banks of the Euphrates, he spent his childhood in the ’70s training for a job he never knew he’d have. He rose each morning before dawn and walked out into the streets with his father, a shop owner. Together they wandered Raqqa’s Eastern Market, a miles-long stretch of vendors selling eggplant and tomatoes, coriander and baharat. His father taught him how to eye the freshest produce and pick the most flavorful spices, how to negotiate prices with vendors and farmers by developing trust.

Raqqa’s culture was tribal, vastly different from the cosmopolitanism of Syria’s biggest cities, Aleppo and Damascus. He spent his evenings in the “tribe house,” a home shared by members of the Taha al Hamed tribe. They used the home as a communal space, and more importantly, to greet visitors with extravagant welcome. Travelers were fed and given shelter, poured coffee heated over a fire, told they could stay as long as they liked. When one of Riyad’s cousins tried to open a hotel, the tribe shunned him. So much of their culture was built on nourishing and welcoming strangers. Hospitality, they believed, should never come with a price.

His father’s mother taught him to make ghee and cheese, spent days sitting with him on the kitchen floor, smoking roll-up cigarettes while teaching him to chop and peel vegetables she would cook for their family’s feasts. His mother’s mother showed him how best to mix spices, taking the kind of herbs his father bought in the Eastern Market and showing him how in combination they could take on superpowers, infusing dishes with flavors unlike any he’d taste elsewhere.

Still, though, he never imagined he’d become a chef. Not when he went to college, where he studied law at the University of Aleppo. Not when he decided to move to the United States, hoping to become an expert in this country’s Constitution; not even when Raqqa’s most famous hummus master pulled him aside and taught him his secret recipe, intended as a going-away present for Riyad because the chef so revered Riyad’s father; not even when his grandfather told him, just before his departure, “I hear they like our food in the West. Cook them food, and teach them about Islam.”

My identity is wrapped up in taking care of people who work for us. It’s hard to grapple with that loss.Andrew Hoffman, Comal

Riyad still didn’t want to become a chef when he moved to the United States and started cooking in a Long Beach Italian deli, where he mastered kitchen Spanglish before English and where the restaurant’s Italian owner gave him a piece of advice that has made Riyad chuckle ever since: “You have to use your accent,” he said. “White people love that. It makes the food seem more authentic.”

Living in Southern California in the ’90s, Riyad fell in love with Linda Bailey, a woman from Tennessee, got married, became an American citizen, and had two sons. Along the way, he cooked extravagantly, just as his grandmothers had, but only for himself and his family and their occasional guests. He built a middle-class life managing a wine shop in Santa Barbara. It was only after moving to Tennessee in 2006, to be closer to Linda’s family, when Riyad applied to job after job after job with no success, that a friend from the local mosque suggested he open a restaurant. He would even invest the money needed to get the business off the ground.

And so, in 2007, Café Rakka was born. Riyad made the bet that he could sell Syrian food to American palates in a county that is overwhelmingly white and conservative. He cooked chicken and lamb, rice and falafel, making cheese the way his ancestors had, hummus just like the master chef of his hometown. He imported spices from Syria, mixed them just as he’d long ago been taught. He scoured Tennessee for the freshest ingredients, just as his father had done in the Eastern Market all those years ago. Though he loved the life he’d built in America, he still ached at times for Raqqa. In his restaurant, Riyad believed he’d carved out a small outpost of his own.

Business built slowly. The first time a customer arrived, he stood over her table to watch her eat, desperate to hear sounds of approval, until his wife called him back to the kitchen so the woman could dine in peace. (“It’s creepy!” Linda said.) When another early customer walked out of the restaurant without ordering after saying he wanted “American food,” Riyad wanted to chase him down and beg him to give his cooking a proper chance. Whenever diners seemed confused by his chalkboard menu—in part because he spelled hummus “hummice” and chickpeas “chick bees”—Riyad told them to have a seat so he could bring out a few samples for free. Near the lowest point of 2008’s Great Recession, he gathered staff to tell them he wasn’t sure he had enough money to cover their next paychecks. He went for a walk with Linda that night, by the lake there in Hendersonville. “You’re not a failure,” she told him. He tried to believe it was true.

He scraped by, but just barely, as drop-ins became regulars and regulars became friends. “This is how you build a business,” he says. “You take your time. You build trust.” In 2010, he caught the attention of the Food Network and got a segment on Guy Fieri’s Diners, Drive-ins and Dives. Between 2014 and 2019, readers of the Nashville Scene voted Café Rakka the best restaurant in Sumner County five times. During Syria’s civil war, when his hometown of Raqqa was overtaken and terrorized by ISIS, becoming the terrorist group’s “de facto capital,” many regulars never even noticed the connection. (Years ago, Riyad had decided to spell his restaurant “Café Rakka” because he thought using the letter K somehow seemed less “foreign” than Q.)

Riyad has had opportunities to expand. They tend to follow the same pattern. Investors approach. Talks begin, then heat up, until eventually they break down. Riyad tends to worry that if he relinquishes control, his food’s quality will suffer. He can’t bear the thought. He doesn’t serve alcohol, which drives profits for many restaurants. He doesn’t have a hip or fancy ambience. “Quality,” he says, “is everything for me.” And so he is still here, well known locally but still unknown to many diners in nearby Nashville, operating a single small restaurant, subject to the industry’s volatility and thin margins. In that sense, he’s like many others in the business.

“Our profits in this industry are, at max, an average of 5 percent,” says Jessica Koslow, chef and owner at Los Angeles restaurants Sqirl and Onda. “That doesn’t allow for a cushion.”

When the coronavirus began to spread across the United States, many restaurants closed and laid off staff in a matter of days. It can seem cruel, leaving employees jobless overnight, but most restaurants lack access to the cash reserves required to sustain periods when business disappears. Says Marcus: “That coupled with rising commodity prices and skyrocketing real estate has put all of the industry in this really precarious position. All of that has created a perfect storm for what’s triggering this crisis today.”

Six weeks ago, many restaurant owners knew that COVID-19 would disrupt their business, but not how severely. Hoffman remembers business starting to dip in late February. San Francisco declared a state of emergency on February 26, making it one of the first cities to do so. Across the Bay Bridge in Berkeley, Hoffman says diners were already staying home. As days passed, business ground to a halt. “The conversations were changing so fast,” he remembers. “At first, we were just reacting to the dip in business, adjusting some of our prior expectations. Then the conversation turned to, ‘Where can we staff leaner? Should we adjust our hours?’” They made tweaks to the menu but quickly realized they didn’t matter. People weren’t avoiding the food. They were hiding from the virus. By the night of Saturday, March 14, the staff at Comal had resigned themselves to the inevitable. “That night, all of a sudden it felt clear,” Hoffman says. “We have to shut it all down.”

They did so the next day, leaving their staff of 125 employees without work. “It’s like a big team,” says Hoffman. “And the team just got benched.”

As the weeks passed in Tennessee, the staff at Café Rakka kept working. Araceli Picano, the sous chef, told me she prefers it that way. For her, the fear of unemployment overshadows the fear of the virus. “I’m very worried,” she says. “It’s very hard right now.” Even as business cratered, Riyad avoided laying off employees. Anyone who wanted to be taken off the schedule could isolate at home. But anyone who wanted work could still get shifts. Still, hours were cut. Job descriptions changed. Dishwashers became prep cooks. Servers turned into delivery drivers. “We can’t have as many people in the kitchen as we used to,” Picano told me during the lull in one of her shifts. “It’s too dangerous. You have to share your time.” But giving up time means giving up pay.

Yes, we are critical to the fabric of communities—we are anchors, we are lighthouses. All of that is true. But from an economic standpoint, we’re even more powerful.Camilla Marcus, West-Bourne

Araceli is the breadwinner of her family, and she saves enough money to support her aging parents back home in Mexico City. Rafa Lima, the prep cook, grew up in Ecuador but has made a home in kitchens across the United States. His paycheck covers his mortgage and supports his wife, who can’t work due to health conditions. He has worked at Café Rakka for 11 years, longer than any other employee, and Riyad calls him “the backbone” of the kitchen. “I love my job,” Lima says, “even though right now, everything is sad.” Mohammad Khader works as the second sous chef, behind Araceli. A native of Jordan, he’d been working at a bakery in Nashville before deciding to move to Hendersonville and join Café Rakka. He likes the collaborative atmosphere, the fact that he feels like he’s always learning. Every night, he and Riyad, both devout Muslims, go to a back room to roll out their mats together and pray. Lately, though, his wife has been worrying every time he leaves the house. She obsessively tracks the number of confirmed cases in their county, begging him to be careful. “It’s really hard,” Khader says. “I can’t stay in the house. If I do, I can’t pay my rent, my bills. I told Chef Riyad, ‘As long as you are here, I am here. I am with you.’”

Figures from Madonna to Andrew Cuomo have referred to the pandemic as an “equalizer.” It has killed poor and wealthy, has infected professional athletes, has sent one of the most powerful men in the world, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, to the ICU. It is most disruptive, though, to members of the poor and the working class. White-collar professionals work on laptops from home offices and chat with colleagues on Zoom. For many in restaurants and other so-called “essential” fields, staying at home means going without pay, while earning a living means risking health and safety.

All of this has weighed on Koslow, the chef at Sqirl and Onda. More than two weeks into California’s “shelter-in-place” order, she kept both restaurants open, offering only takeout and delivery. At Sqirl, she says, “We actually stayed really busy. People trusted us in their homes just like they trusted us in the restaurant.” From a business perspective, she says, “it was sustainable.” As time progressed, though, she encountered another problem. “The hard part was the true fear on the part of staff and employees,” she says. Some chose to self-isolate as soon as the virus emerged as a clear threat. Others, she says, “were trying really hard to stay on, but even for them, the fear eventually takes its toll.” Staff worried whether other employees had ridden to work on public transit, thereby exposing themselves to higher risk of contracting the virus. Postmates drivers sometimes stood too close to employees or arrived to pick up orders without wearing masks or gloves. “Those little things would spiral,” she says. “Mentally, it was just too much.” Since closing, she has converted Sqirl into a relief center for hospitality workers, partnering with the Lee Initiative to give out 300 meals a day and keep a few staff members employed.

The American economy has never endured a crisis so immediate and acute. Nearly 10 million people applied for unemployment insurance in the past two weeks, the most since those statistics have been counted—by a factor of more than 10. The unemployment rate is likely already in the teens, and could hit the Great Depression’s peak of 25 percent. And with so much of that damage concentrated in one industry, it’s still difficult to sift through the wreckage.

In this restaurant, my heritage is alive.Riyad

Drew Herrmann, a labor attorney at Herrmann Law in Fort Worth, often represents restaurant workers in lawsuits against their employers. Lately, his firm has been fielding calls from workers who no longer have jobs. “We don’t typically deal with unemployment claims,” he says, “but of course when clients are calling we’re willing to help. People need to know what’s available to them.” Many restaurant workers, though, don’t have access to unemployment insurance. The benefit covers American citizens and holders of work visas, but not undocumented immigrants, who fill kitchens across the country. “There is no reason for them to be excluded,” says Robin Engle of OneAmerica, a Seattle-based organization dedicated to immigrant and refugee advocacy. “Our economy depends on people who are undocumented. Our food system especially, from the folks out there in fields to the folks working in kitchens. Our economy could not survive without them, and they pay taxes to the federal government every year. But in a moment like this, the safety net that’s available to everyone else is unavailable to them.”

All of Riyad’s staff are in the country legally, he says. But even for authorized immigrants, navigating the bureaucracy of a foreign state can feel overwhelming. “A lot of these people are afraid of the government,” he says. “They don’t want to ask for help. They’re afraid that if something bad happens, they’re going to end up on some kind of list.” Though Riyad sees his staff as a tribe, it’s hard not to notice the divisions. “Some of the kids up front are either living with parents or have parents who can support them if they need to,” he says. “In the kitchen, they are the parents. The kids in their families are trying to get support from them.”

The night Riyad and his employees gathered in the kitchen, debating whether to stay open, none could think of better options than continuing to work for as long as they could. “For a few of them,” he says, “it felt like they see this as a battlefield. Like there’s glory in being the ones who are still here, still working, making food for everyone else who is sitting at home.” Riyad tried to talk them out of that mind-set. “Now for me?” he says. “I have to think like that. It’s my business, my legacy, my heritage. But they need to be thinking about what’s best for themselves and their families.”

The night they gathered, Congress had just passed the CARES Act, a $2 trillion stimulus package meant to help stabilize the economy amid the COVID crisis. Neither Riyad nor his employees had yet had time to study the bill. Some didn’t even know it existed. None knew how much it would help. In the days since, that picture has become clearer. The bill expands unemployment insurance, adding $600 per week and extending the benefit up to 39 weeks. (Previously, some states capped it at 26 weeks, others at 13.)

I love my job, even though right now everything is sad.Rafa Lima, Café Rakka

Perhaps more critically for restaurants, the bill includes the Paycheck Protection Program, which can be used by small businesses to cover payroll and rent for a period of eight weeks. For businesses who don’t lay off employees—or who make sure to hire them back by June 30—the loan for that eight-week period is eligible to become a grant. It is, essentially, free money. For Riyad, the bill relieves some of the pressure he’s felt to do everything he can to keep paying employees, even as revenue cratered. “If I know they can still get paid through this loan,” he says, “then maybe we can finally take a breath.” He could imagine closing temporarily, continuing to pay his employees while they isolate at home. “Maybe we can hunker down and weather this.”

The Paycheck Protection Program loans can represent one step toward helping restaurants survive. “It’s certainly a positive step,” says Marco Costales, a Los Angeles–based attorney who represents restaurants and bars. “The federal government absolutely had to do something.” So far, though, the program’s rollout has been halting and disorganized, the loans slow to arrive. For many business owners, it’s unclear whether they would be better off using the loans to pay employees, or laying off employees to allow them to seek the expanded unemployment insurance. “A lot of businesses know their revenue isn’t going back to February levels by the beginning of May, so they might be better off using other provisions of the CARES Act, like the expanded unemployment benefits,” Betsey Stevenson, a University of Michigan economist, told The New York Times.

For many in the industry, it’s clear the CARES Act’s provisions aren’t enough. “Our real concern,” says Tom Colicchio, the founder of Crafted Hospitality and head judge on Top Chef, speaking on a conference call with reporters last week, “is that just two months of payroll doesn’t get us to when our doors are open.” Many anticipate that the crisis’s impacts will linger far longer than two months. Even when shelter-in-place orders are lifted, many Americans won’t want to return to crowded restaurants and bars. “If you’re at a restaurant, and someone starts coughing at the table next to you, what are you gonna do?” says Riyad. “I know what I would do. I would leave.”

On April 6, the IRC wrote a letter to Congress, asking it to expand the PPP program and to launch a “Restaurant Stabilization Fund,” among other requests. The case made by many restaurant owners is simple: The CARES Act took steps to provide short-term relief for employees. Now, though, restaurants need more support for the businesses themselves to survive, and for those employees to have jobs they can return to when restaurants reopen. “We’re not looking for a bailout,” says Colicchio. “Our industry was forced to shut down. We’re just looking to get back to work, when we can get back to work.”

While Riyad has gone to work every day of the past few weeks wondering whether he should close, some restaurant owners made the choice to shut down almost immediately after the crisis hit. Camilla Marcus closed West-Bourne on March 15. She believes the government should have forced other restaurants to do the same. “Our DNA is to take care of people,” she says. “During disasters we jump in and feed people and make sure they’re calm and nourished. What was hard was realizing that the scale had been tipped. Us staying open was making the problem worse.”

At first glance the case appears straightforward: People need to remain far apart from other people. Bringing them together—even just to pick up takeout or delivery orders—could further spread the disease. For the employees, the risk is even greater; few kitchens are equipped to keep workers 6 feet apart. When talking with Riyad, I mentioned the decisiveness of Marcus and so many other chefs who closed right away. He seemed almost envious. He also connected his experience as an immigrant to his desire to remain open as long as he could. “We can’t help it,” he said of himself and other immigrant restaurant owners he knows. “We’ve survived so many crises and calamities in life, and this is one of them. We feel like we can’t stop. We have to keep going to survive.”

The hard part was the true fear on the part of staff and employees.Jessica Koslow, Sqirl and Onda

I point out that keeping going could also mean death. “Yeah,” he said. “It feels a little like death either way.”

I tried to describe for Marcus what Riyad was going through. He owns a smaller restaurant in a sparsely populated county in a state that waited until April 2 to issue a “stay-at-home” order. And though he follows the news closely, he exists outside the Extremely Online cultural bubbles that have developed new codes of ethics seemingly overnight, shaming anyone who happened to venture within 6 feet of anyone else. He wants to be safe, but he doesn’t want to lay off his staff, and he’s pained by the prospect of losing the restaurant that has been his life’s work. “It’s absolutely brutal to be in that position,” she said. “How do you tell your team they can’t work when some of them want to work even though it’s not safe? That’s why I think we’ve needed leadership from the government on this. It’s so hard to ask every single restaurant owner to decide whether to risk their employees or not. It’s an impossible challenge and brutally unfair.”

Back in 2013, Riyad’s hometown spiraled into chaos. Syria’s civil war had been raging for two years. Raqqa had fallen from the Assad regime into the hands of the rebels. Riyad went to work every day at Café Rakka, and he went home every night to his wife and his sons, but his mind and heart were elsewhere, thousands of miles away on the banks of the Euphrates, where his mother and brother and sister were still in the home of his childhood, trying to survive the war.

He couldn’t stand it. He had to go see them, to try to convince them to flee Raqqa before it was too late. He told Linda. “Go,” she responded. She was afraid, but she knew her husband had to make the journey. He needed to travel toward the danger, so that he could help the rest of his family reach safety.

Riyad has found himself thinking about that trip lately. “It felt then a little bit like it feels here, right now,” he says. Obviously, the differences are vast. Syria’s danger felt visceral and urgent, death arriving day and night, delivered by regime bombs. War’s destruction was total. But still, he says, in the earliest days after Raqqa fell, “There was something about being afraid to go outside. There, you walked the streets and you could see the fear on everyone’s faces. They were just trying to get where they were going as fast as they could. It feels like that now. Everyone is so afraid.”

It’s so hard to ask every single restaurant owner to decide whether to risk their employees or not. It’s an impossible challenge and brutally unfair.Marcus

Linda told him to go into a war zone in 2013, but a big part of her wants him to stay at home now. Over the weekend, Riyad shortened Café Rakka’s hours, announcing they’d open only Wednesday through Saturday, from 2-8 p.m. He’s still considering closing altogether, at least for a while, if he ensures his employees can get by with funds from the CARES Act. “Psychologically,” he says, “I think everyone needs a break.”

Maybe it’s necessary. But it’s no less painful. “When I am in that restaurant,” he says, “and I hear the music of the plates and the forks and the spoons, that is the most beautiful symphony of my life.” It calms him, he says, fills him with pride in himself and his culture, in the father and the grandmothers who long ago passed away. Now, though, “that sound might be gone for a long while,” he says.

He’s making plans for the future. During this crisis, he’s enabled online ordering, something the restaurant never had before. He’s begun selling family meal trays, and has started moving toward other ways to get his food into people’s homes. He’s also begun serving something he calls “Elixir Tea.” It’s an ancient recipe, made from wildflowers that grow near the Euphrates, and for centuries, members of his tribe have drunk a version of the tea whenever they felt sick, believing it boosts their immune systems. For years, Riyad has had the flowers shipped from Raqqa to Tennessee, and he’s often made a version of it, which he calls “Sick Tea” and gives to family and friends. He doesn’t claim it as a cure, only as something he and his ancestors have turned to for centuries in times of sickness. Even during the war, he has found a way to get bags of the wildflower shipped from Raqqa to Aleppo to Turkey and on to Tennessee. He’s made more than 500 gallons of the tea since the arrival of COVID-19.

And for as long as the restaurant remains open, he’ll keep the tea on hand. But he doesn’t sell it. He follows the tradition of Raqqa’s tribe houses, where strangers were welcomed with no conditions. For anyone who shows up at his doorstep and asks, he gives the tea away for free.