Social Distancing Diaries: Men’s Olympic Swimming Is the Internet’s Most Rewatchable Epic

Readily available across the web, high-level swimming videos are the perfect distraction in this strange time. And there’s no better place to start than the rise of Ian Thorpe and Michael Phelps.The sports and pop culture calendars have paused. The safest thing that you can do right now is stay inside. And millions of people are looking for creative ways to pass the time. The Ringer is here to help. We’re starting a series called the Social Distancing Diaries, with our staff’s ideas for finding comfort, joy, community, or distraction while doing your part to flatten the curve. In the coming weeks, we’ll be diving into what we’re passionate about and want others to discover—from bidets to buried treasure and everything in between.

In this time of social distancing, many of us are lucky enough to have no patriotic duty other than to stay at home and not spread disease. But with no sports, no access to bars and restaurants and movie theaters, and limited interactions with other humans, millions of people are already incredibly bored. In an effort to liven up the abyss we’re all staring into, every Tom, Dick, and Harry who talks about pop culture on the internet has published some list of recommended streaming media to help pass the time. (Not least among such outlets is The Ringer, home to “The Streaming Canon,” a list of dozens of films and TV shows and where to find them.)

But the best, most rewatchable epic serialized drama out there is not Game of Thrones or The Expanse or The Lord of the Rings. It’s Olympic swimming.

High-level swimming is a great rewatchable sport for two reasons. First, the sheer number of events and competitions lends itself to YouTube rabbit holes that run miles and miles deep. Second, while individual athletes might be familiar after repeated TV exposure during the Olympics, the actual results often blur together. For example: Everyone remembers Ryan Lochte, but nobody remembers how he did in the 200-meter freestyle at the 2010 Pan Pacific Championship, which makes that race as dramatic now as it was 10 years ago.

Videos of past Olympics—and World, European, and Pan Pacific championships—are all out there on the internet, from sources that range from NBC Sports to sketchy YouTube channels with Russian titles and glitchy audio feeds. You can jump from meet to meet or event to event at random, or scoop out a potpourri of highlights for Katie Ledecky or Adam Peaty or Park Tae-hwan. But the best way to consume international swimming is by picking up a narrative thread that ties athletes and countries together for years.

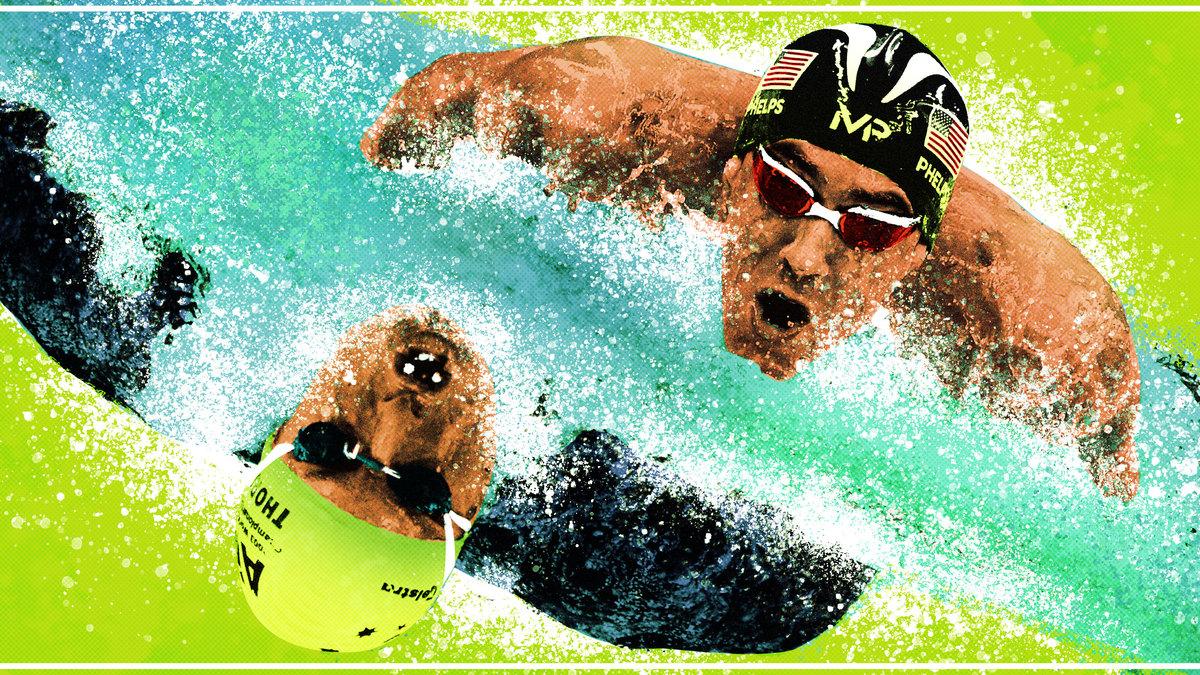

The most glamorous among these is the passing of the torch between the two most famous male swimmers of the 21st century: Ian Thorpe and Michael Phelps. What follows is a selection of six races across three Olympic games that track Thorpe’s unique career and illustrate how he blazed the trail for Phelps to become an international swimming superstar.

Episode 1: Men’s 4x100 freestyle relay, Sydney, September 16, 2000

The men’s freestyle relays represent the fastest, flashiest form of Olympic swimming, and leading up to the 2000 Olympics, the United States had long been the dominant force in these events. The U.S. was undefeated all time in the men’s 4x100 and had won eight of the previous 10 gold medals in the 4x200. Australia had beaten the United States in a men’s Olympic freestyle relay just twice, most recently in 1956.

But like in 1956, when the Olympics were held in Melbourne, Australia had home-field advantage before a raucous Sydney crowd. And most importantly, the Aussie roster boasted two up-and-coming superstars: 23-year-old sprinter and butterflyer Michael Klim, who’d won seven medals at the 1998 World Championships in Perth, and 17-year-old Ian Thorpe. At the 1999 Pan Pacs, Thorpe won gold in four freestyle events, including the 4x100 relay, the first time the United States had ever lost that event at that meet.

Thorpe’s competitive credentials alone would have made him a celebrity in swimming-obsessed Australia, but it didn’t hurt that he looked like he could have been a member of the globally popular Backstreet Boys. He was also the poster boy for the growing importance of technology in the sport. Reducing drag is of paramount importance in swimming now, but up to and including the 1996 Olympics, most male competitors took the pool in briefs. Many didn’t bother to shave their heads or wear swim caps.

By 2000, though, specialized hydrodynamic swimsuits had become the norm, ranging from full-length pants to overalls-style suits to Thorpe’s black Adidas bodystocking, which ran down to his wrists and ankles. Thorpe’s swimwear was not only effective—increasing his buoyancy and the ease with which he moved through the water—it also made him the most recognizable man in the pool.

Four years earlier, that distinction would have gone to American superstar Gary Hall Jr., a 6-foot-6 second-generation Olympian who won four medals in Atlanta and wore a silk boxer’s robe to the pool deck. If Thorpe was the Backstreet Boys, Hall was Green Day; he’d been suspended by FINA after a positive test for marijuana in 1998, back when that was still scandalous. And as the superstar anchor of the seven-time defending Olympic champions in the 4x100 freestyle, Hall said Team USA would “smash [the Australians] like guitars.”

That would go down as the most famous line of trash talk in swimming history, and an example of hubris straight out of Homer.

On the night of the Olympic final, Klim swam the leadoff leg of his life. His time of 48.18 seconds broke Russian legend Alexander Popov’s six-year-old individual 100-meter world record and put seven-tenths of a second into American leadoff man Anthony Ervin. But while Australia had more star power with Thorpe and Klim, the Americans had more depth. Neil Walker and Jason Lezak narrowed Australia’s lead to a matter of inches in the middle two legs and left the race up to Hall to finish.

Even though some of Thorpe’s biggest international triumphs came in sprint-length relays, he was a middle-distance freestyler first and foremost. Hall, by contrast, was one of the best sprinters of his generation. The quicker American streaked out to a lead of nearly a meter by the turn, but in the final 40 meters of the race, Thorpe was able to maintain his pace and gradually reel Hall in. Hall swam a fractionally quicker leg than Thorpe on time, but the Australian—a teenager racing for the third time that day—out-touched him by less than a quarter of a second.

Thorpe leaped out of the pool to celebrate with his teammates while Klim turned to the stands and, recalling Hall’s comments before the race, treated the home crowd to some air guitar.

Episode 2: Men’s 200-meter freestyle, Sydney, September 18, 2000

Shortly before his dramatic anchor leg in the 4x100 freestyle relay, Thorpe had won his first individual event, the 400-meter freestyle. He finished in a world-record time of 3:40.59, almost three seconds ahead of second-place finisher Massimiliano Rosolino of Italy and six and a half seconds ahead of bronze medalist Klete Keller of the U.S.

That shockingly dominant debut, followed by the historic win in the relay, made it seem like Thorpe would cakewalk to gold in each of his first four Olympic races. Thorpe went into the games as the overwhelming favorite in the men’s 200-meter freestyle, having recorded the four fastest times in history. None of the medalists from Atlanta had returned four years later. Klim, the reigning world champion, skipped the event, and none of the Americans from the 100-meter relay final stretched out to challenge Thorpe in the longer distance. His major competitors were the swimmers who’d finished alongside Klim on the podium at the World Championships: Rosolino and 22-year-old Dutchman Pieter van den Hoogenband.

As a teenaged Olympic debutant in Atlanta, van den Hoogenband had finished off the podium in all six events he contested, and he won only one individual medal—a bronze—at the world long-course championships in 1998. It wasn’t until he set a new world record in the 200-meter freestyle semifinals in Sydney that he emerged as a real threat to Thorpe. Like Hall and Klim, van den Hoogenband was primarily a sprinter, which meant that his top-end speed was greater than Thorpe’s. Thorpe would have to beat him by staying close and coming home strong, as he had against Hall in the relay and in a world-record victory over Klim in the 200 at the Australian Olympic trials.

It took several seconds for the excited Australian crowd to quiet down enough for the race to start, but when it did, Thorpe, van den Hoogenband, and American Josh Davis quickly distanced themselves from the other five swimmers. Davis held pace for 100 meters before falling off, after which it seemed like Thorpe—who’d matched the faster Dutchman stroke-for-stroke to that point—was well positioned to shift into a higher gear. Thorpe made the final turn with a slight lead, but in the final leg, it was van den Hoogenband who found an extra turn of speed to win by half a second.

This was Thorpe’s first defeat in Olympic competition and an introduction to superstardom for van den Hoogenband, who’d go on to absolutely torch Hall and two-time defending champion Popov in the 100-meter final and take bronze in the 50 meters. By all accounts, Thorpe and van den Hoogenband were friendly rivals—in contrast to Thorpe’s chilly relationship with Phelps—but this was a momentous occasion: the first time the Thorpedo met an adversary he could not overcome.

Episode 3: Men’s 4x200 freestyle relay, Sydney, September 19, 2000

This is the least dramatic race in the series, but nothing illustrates Thorpe’s dominance better. In contrast to the 4x100, in which Klim led off and Thorpe anchored, Australia led off with its two fastest swimmers in the hopes that they could wrap up the gold medal in the first half of the race and coast to victory.

That’s exactly what happened. Thorpe swam the fastest leadoff leg by three and a half seconds. Klim followed up with a second leg that extended the lead by a tenth of a second and put two or three seconds into the rest of the field. By the time Klim was done, Australia was so far ahead of the field that the TV camera was having a hard time keeping the top-three teams in the same shot. The Australians, mostly thanks to Thorpe, won by more than five seconds and smashed their own world record in the process. Thorpe went on to win a fifth medal by swimming in the heats of the 4x100 medley relay, before Klim anchored the team to silver in the final. Though the upset loss to van den Hoogenband kept Thorpe from his anticipated 200-400 double, the 17-year-old left his home Olympics as the most decorated athlete at the games.

Episode 4: Men’s 200-meter freestyle, Athens, August 16, 2004

At the 2001 World Aquatics Championships, Thorpe avenged his Olympic loss to van den Hoogenband. He earned gold medals in the 400 and 800 meters and led Australia to a sweep of the men’s relays. Meanwhile, Phelps, who at age 15 had finished fifth in his only event in Sydney, won his first world championship in the 200-meter butterfly. The following summer, Thorpe won the 100-, 200-, and 400-meter freestyle at the Pan Pacs and faced Phelps head-to-head in major international competition for the first time as he anchored the 4x200-meter freestyle and 4x100-meter medley relays. Australia won the former by nearly three seconds, while the U.S. set a world record to take gold in the latter.

At the 2003 World Championships, Phelps won six medals, including a head-to-head individual matchup over Thorpe in the 200-meter individual medley. That prompted Speedo, Phelps’s sponsor, to offer the American a $1 million prize if he beat Mark Spitz’s record of seven gold medals at the 2004 Olympics.

By 2004, the 29-year-old Hall was no longer one of the premier 100-meter sprinters in the world, and injuries had all but ended Klim’s career. But Phelps’s emergence as a global superstar gave men’s swimming new life in the international sports media. Here was a brash young American with the potential to put in world-class performances in an unprecedented variety of events, and to dethrone Thorpe as the biggest star in the sport. Most importantly, in contrast to the affable van den Hoogenband, both Phelps and Thorpe were the kind of competitors who not only wanted to win at all costs, they wanted to beat their opponents.

Phelps was famous for using specific opponents as motivation. When Ian Crocker beat Phelps in the 100-meter butterfly at the 2003 World Championships, Phelps put a poster of Crocker up on his bedroom wall as a reminder. Thorpe did his best to squash the budding rivalry, but Phelps was determined to get a shot at the world’s best swimmer. After Phelps qualified to swim nine events at the U.S. Olympic trials in 2004, he scratched the 200-meter backstroke to focus on the 200-meter freestyle, specifically so he’d have a chance to race head-to-head with Thorpe. Thorpe, meanwhile, said Phelps’s goal of tying or besting Spitz was “unattainable.”

The leadup to the Athens Games was uncomfortable for Thorpe. He’d parted with his longtime coach in 2003 and was later disqualified from the 400-meter freestyle at the Australian Olympic trials when he fell off the blocks before the gun; it was only after massive public pressure that the second-place finisher, Craig Stevens, pulled out of the race to allow Thorpe the chance to swim.

And swim he did. Thorpe defended his 400-meter gold by beating countryman Grant Hackett and Keller, the top American, on the first day of swimming competition. Phelps won gold in the 400-meter individual medley the same day, and the following night, the two faced each other for the first time in Olympic competition in the final of the 4x100 freestyle relay.

Both came away disappointed when Roland Schoeman of South Africa—the surprise top qualifier—leaped off the blocks and gave his team a lead of more than a second. Klim came out of the pool fourth, while the American leadoff man, Crocker, was dead last at the end of his stint. Neither team was able to make up that ground. South Africa led wire-to-wire, and the U.S. finished a humiliating third after van den Hoogenband chased down Lezak in the final leg. By race’s end, Australia had dropped all the way to sixth. Phelps’s dream of eight gold medals was dead on arrival, and Thorpe’s Australia, who had dominated the Americans in international competition, was a total afterthought.

The day after the crushing relay loss, Phelps and Thorpe returned to the pool for a race with more star power than any individual swimming event in Olympic history. Six of the eight competitors in this race were Olympic medalists, including van den Hoogenband, Hackett, Keller, and Italian Emiliano Brembilla.

Thorpe had reclaimed the world record from van den Hoogenband in 2001, but the Dutchman once again entered the final as the top seed in the race. Thorpe and Phelps beat van den Hoogenband off the blocks, but the Dutchman quickly passed both to hold the lead at 50, 100, and 150 meters. Phelps dropped to third early on and stayed there, but Thorpe was able to remain close behind the leader. While van den Hoogenband was able to stay out in front in Sydney, he tired down the stretch this time and Thorpe passed him on the final turn to avenge his loss in Sydney.

Phelps had taken his first real shot at Thorpe and lost not only the race, but his chance of beating Spitz’s record at the 2004 Olympics. He and Thorpe would meet only once more in Olympic competition: the following night’s 4x200 relay.

Episode 5: Men’s 4x200 freestyle relay, Athens, August 17, 2004

In 1997, the 14-year-old Thorpe made his debut at a major international swim meet, the Pan Pacific Championships in Japan. There, he and an Australian team that included Klim and Hackett finished second to the United States in the 4x200 freestyle relay. That was the last time an Australian team with Thorpe lost this race at either the Olympics, Pan Pacs, or long-course World Championships—a winning streak of seven years.

Even with Klim and Hackett on the 2004 team, Australia’s hopes of retaining the gold medal rested primarily with Thorpe. In four previous individual Olympic matchups, Thorpe had absolutely torched Keller, the American anchor swimmer, each and every time. And four years earlier, Keller had nearly coughed up the silver medal in this event when Rosolino and van den Hoogenband chased him down on the final leg. If Thorpe went into the water even within a few seconds of Keller, the Australians could all but count on taking home the gold medal.

So the first three American swimmers knew they had to hand Keller a big lead, and they did. On the first leg, Phelps beat Hackett to the wall by more than a second. A 20-year-old Ryan Lochte, swimming the first event of his Olympic career, out-touched Klim by another tenth of a second, and by the time Peter Vanderkaay came home for the final handoff, Keller had a head start of about 1.5 seconds on Thorpe.

That lead vanished almost immediately. With Thorpe’s long, smooth strokes and his 6-foot-5 frame seemingly elongated by his black suit, he looked like a shark chasing Keller through the water. After about 35 meters, Thorpe’s head was at Keller’s shoulder. It looked like a matter of time before Thorpe would make the decisive pass and disappear for good.

But somehow, that pass never came. For more than three lengths of the pool, Keller kept the greatest 200-meter freestyler ever in his hip pocket, even though he couldn’t see Thorpe over the decisive final few meters. Every time Thorpe grabbed another handful of water, it looked like he’d finally squirt past Keller, but each stroke ended with the two in almost exactly the same position they’d started. Keller stayed in front of Thorpe at every turn, and touched the wall 0.13 seconds ahead of the defending champion.

After the 2004 Olympics, the 21-year-old Thorpe withdrew from high-level competition—the 4x200-meter relay in Athens would be the last time he and Phelps ever shared the pool. Though he attempted to come back several times, Thorpe never returned to a major international meet, and retired in 2006. In the years after his career ended, Thorpe struggled with depression and alcohol misuse, which he revealed in a 2012 memoir, before coming out as gay in a 2014 television interview.

Thorpe’s five Olympic gold medals are the most ever for an Australian athlete, and his nine overall medals are tied for the Australian national record with fellow swimmer Leisel Jones. While his total medal haul is dwarfed by the likes of Phelps and Lochte, Thorpe competed in far fewer events and had a much shorter career—only 10 total events, in which he finished off the podium just once.

Phelps, by this point, was well on his way to becoming the most decorated Olympian ever. He entered eight events in Athens and apart from his losses in the 4x100 freestyle relay and 200-meter freestyle, took home gold every time. With four years of additional training, and Thorpe and van den Hoogenband out of the way, he’d have a clear path to an eight-event gold-medal sweep in Beijing.

Episode 6: Men’s 4x100 freestyle relay, Beijing, August 11, 2008

After Thorpe’s exit from international competition, Phelps dabbled in new events at the 2005 World Championships and 2006 Pan Pacs. It wasn’t until the 2007 World Championships that Phelps returned to his Athens program at a major international meet. There he won seven gold medals, breaking Thorpe’s record of six golds at the 2001 edition, and would almost certainly have won an eighth if his medley relay teammates had not false-started in a preliminary heat.

Even so, Thorpe, who by this point had been retired for years, doubted that Phelps could reach his goal. “I don’t think he can’t do it,” Thorpe told Reuters on the eve of the Olympics. “I just don’t think he will. Look at the competition.”

The competition didn’t seem to bother Phelps in his first event, the 400-meter individual medley, in which he cruised to victory by more than two seconds. But the second event was the men’s 4x100 freestyle relay, which the United States had not won at the Olympics since 1996. They faced a strong Australian team led by Eamon Sullivan, and a favored French squad led by individual world record holder Alain Bernard. In the preliminaries the night before the final, the Americans won one heat in world-record time, but beat Australia by only 0.18 seconds. In the second heat, the French set a new European record, while Amaury Leveaux broke the Olympic record in the individual 100 meters and Frédérick Bousquet swam a 46.6-second anchor leg, going about an eighth of a second faster than van den Hoogenband’s face-ripping relay split in the final four years earlier.

“The Americans? We’re going to smash them,” said Bernard, who’d apparently never heard of Gary Hall Jr. “That’s what we came here for.”

The 2008 final is to this day the fastest relay race in Olympic swimming history. The South African team, which had dominated this event four years earlier, brought back the same four swimmers, turned in a quicker time than they had in Athens, and managed to finish only seventh. This race represents the peak of the technological swimsuit revolution for which Thorpe had been an early standard-bearer. You’ll notice that in 2004, Phelps swam this relay in a suit that stretched from his waist to his ankles, while four years later he and his three American teammates were outfitted in shoulder-to-ankle bib-overalls-style suits covered in black patches. These suits, named Speedo LZR Racers, were made out of polyurethane and were extremely hydrodynamic—so much so that they, and all non-textile suits, were banned from the sport in 2010.

But in addition to this historically fast crop of racers wearing historically quick equipment, the pressure surrounding the race made it one of the most exciting, tense events in Olympic history, maybe all of sporting history.

Sullivan took the Australian team out hard early, turning in a 47.24-second leadoff leg to set a new individual world record by almost a quarter of a second. Phelps, who did not swim the 100-meter freestyle as a regular part of his competitive program, came home second at 47.51, to set a new American record, and in the 12 years since only three American men have gone faster. Phelps handed Garrett Weber-Gale a 0.4-second lead over France, and Weber-Gale chased down Australian Andrew Lauterstein on the second leg to grab the lead for the United States.

It’s worth mentioning here that one of the things that makes this race so special, at least in American sports history, is the call by Dan Hicks and Rowdy Gaines of NBC. Other races on this list have been boosted by great commentary—Australian broadcaster Dennis Cometti’s account of the 2000 4x100 free relay is a personal favorite of mine—but on the 2008 relay, Hicks and Gaines delivered what is, in my estimation, the greatest TV commentary performance in all of sports history.

As much as the American viewing public was enamored of Phelps in 2008, the technical particulars of swimming eluded most sports fans. Hicks and Gaines managed to cram in a ton of information in an easily digestible form, all while roping viewers in by evoking an intensity to match the occasion. If the broadcasters—Gaines in particular—acted like this race would determine the fate of humanity, who were we to argue?

On the third leg, American Cullen Jones matched his time from the previous night’s heats, but unfortunately for the United States, so did Bousquet, who’d been about a second faster. Bousquet passed Jones just 20 meters into the third leg and pulled away from there to establish a lead of more than half a second for Bernard, the fastest swimmer in the race.

Lezak, 32 years old at the time of the race, had raced on the only two U.S. men’s teams that failed to win the 4x100 freestyle at the Olympics and had never won an individual world or Olympic medal of any color. Four years earlier, van den Hoogenband had run him down in the closing stages of this race to deny the U.S. a silver medal behind South Africa. And while Lezak, an experienced relay swimmer, got a much better jump off the blocks than Bernard, the Frenchman quickly reestablished his half-second lead by the turn.

With about 25 meters left in the race, Lezak had inched up on Bernard and cut what had been a body length’s lead in half with a powerful kick off the final turn. It was just after Hicks voiced his resignation that the U.S. would be consigned to a silver medal that the NBC play-by-play man ramped his voice up into a shout: “Lezak is closing a little bit on Bernard! Can the veteran chase him down and pull off a shocker here?”

And over the last 15 meters, he did just that. Jones, standing by himself at the pool ladder after climbing out of the water, took a peek at the scoreboard and leaped up into the air. Phelps and Weber-Gale screamed. Gaines shouted himself into a hoarse soprano, marveling that Lezak “blew away” the fastest relay leg in history by more than half a second.

This race preserved Phelps’s path to eight gold medals in one Olympics and pushed him past Thorpe with 10 career medals, eight of them gold. The rest of the story—the greatest career in the history of swimming or the Olympics—is well-known by now.

After Phelps wrapped up his eighth gold medal—in the 4x100-meter medley relay, anchored once again by Lezak—Thorpe met his former rival in Beijing to offer his congratulations.

“Never in my life have I been so happy to have been proved wrong,” Thorpe told reporters. “I enjoyed every moment of it.”