In ALCS Game 3, Astros starter Gerrit Cole looked as close to beatable as he has for four months. Cole walked five batters, tying a career high, and allowed nine base runners, tied for second most in any start this season (and his most since late June). Cole didn’t actually lose; in fact, he didn’t allow a run, and the Astros won the 16th consecutive game he’s started. But because the Yankees made him work, he threw 112 pitches before exiting after seven innings.

A year ago, a pitch count that high would have made us do a double-take. This October, it’s seemed almost routine. In 2018, no postseason starter threw more than the 108 pitches Walker Buehler tossed in World Series Game 3. In 2019, we’ve already seen eight postseason starts that lasted 109 pitches or more, including Cole’s 118 in ALDS Game 2. Those lofty pitch counts are one manifestation of this month’s most surprising development: After several years of ceding ground to relievers, starters are back in the postseason saddle, at least temporarily.

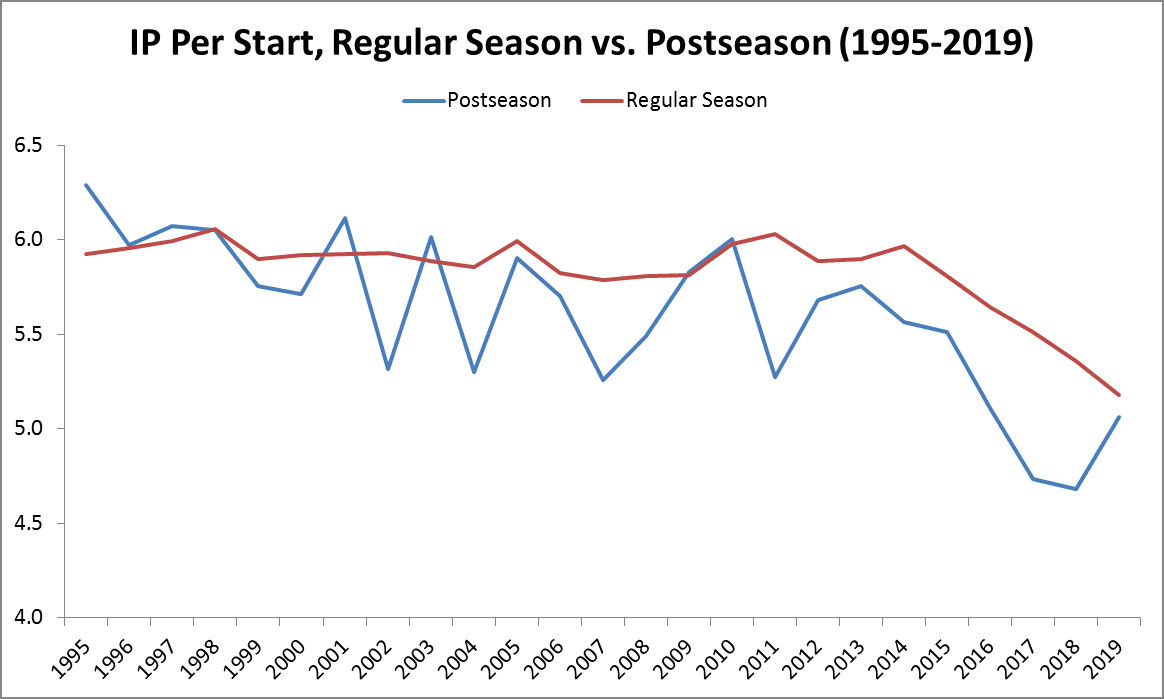

Until this October, the average length of a postseason start had fallen for five consecutive years, reflecting teams’ growing awareness of the times-through-the-order penalty, which saps starters’ effectiveness as they face the same hitters multiple times in a game. Pitch counts have come down over the past two decades mostly in an effort to preserve pitchers’ arms, but the times-through-the-order effect, a more recent focus for teams, is primarily a product of familiarity, not fatigue. In the past few years, a growing awareness of the importance of the penalty has caused teams to pull starters sooner, particularly in the postseason, when the more forgiving schedule allows managers to use their best relievers in a greater percentage of games.

The 2016 season seemed to represent a turning point in this process. The flexible bullpen model that the Indians devised during that summer carried over into October and made bullpens the biggest story of a month when the length of an average start fell sharply to 5.1 innings, a new low in the wild-card era. The next two seasons extended the trend, as teams stockpiled bullpen pitchers in record numbers at the trade deadline and deployed them to record degrees in the playoffs. The starter’s October obsolescence seemed inevitable. As The Atlantic pronounced in October 2017, “Bullpen-heavy postseason series will not soon go away. … For more than a century, starting pitchers have dominated baseball’s postseason. Now it’s the relievers’ turn.”

Last year, starters threw only 3 2/3 more playoff innings than relievers, leaving bullpen pitchers at the doorstep of postseason supremacy. This year seemed certain to be the one when they crossed the threshold and compiled the bulk of playoff innings. In the wild-card games, relievers combined to throw 19 of 35 innings, which got October off to a bullpen-centric start. But starters soon struck back and started lasting longer.

With 27 postseason games played and between six and 11 remaining, the average length of a postseason start has rebounded to about where it was in 2016: slightly above the five-inning mark. This year’s postseason starts have lasted almost as long, on average, as this year’s regular-season starts (which also grew shorter for the fifth consecutive year). Not since 2010 has the gap between regular-season and postseason start length been so small.

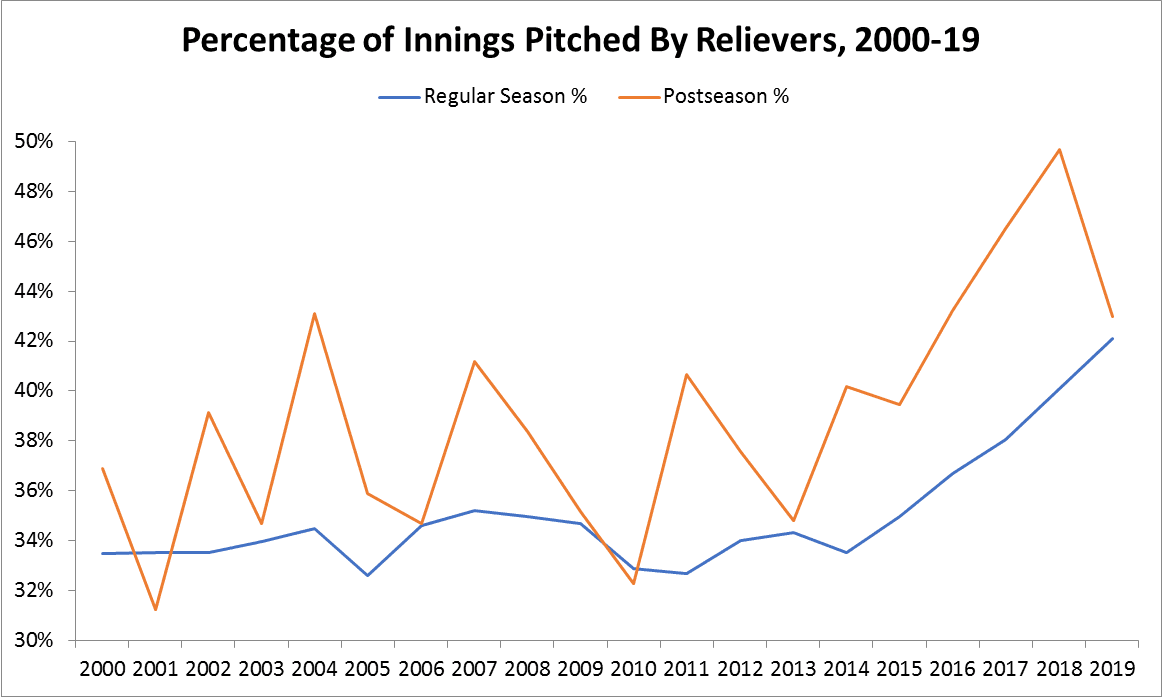

Thanks to that reversal, starters have already surpassed last October’s number of batters faced the third or fourth time through the order. The more managers stick with their starters, the fewer innings remain for relievers to absorb. The graph below shows the percentage of regular-season and postseason innings thrown by bullpens in every year going back to 2000. Each of the past three postseasons featured a higher percentage of innings pitched by relievers than any previous season in the sample. But this year, for the first time since 2015, relievers’ playoff workloads have lightened, even though they continued to increase during the regular season.

Relievers’ regular-season responsibilities have soared in the past several years, but their postseason usage rates have climbed even more quickly. The gap between the percentage of overall innings they threw in the regular season and postseason was widening by the year until 2019, when it’s all but disappeared.

2015: 12.8 percent

2016: 17.8 percent

2017: 22.2 percent

2018: 24.0 percent

2019: 2.1 percent

Despite the developments over the past few Octobers, the greater urgency of postseason play, and the off-day-filled schedule that permits quicker hooks, playoff pitcher usage this year has looked almost indistinguishable from the regular season. So why have starters’ leashes suddenly loosened?

Part of this apparent change of heart is actually attributable to the tendencies of the teams that composed the playoff field. The Nationals and Astros, two of the three remaining playoff clubs, ranked second and fourth in the majors in the percentage of regular-season innings pitched by starters. The Dodgers, Twins, and Braves placed in the top 10 too, with the A’s and Cardinals also ranking in the top half of the majors. Of this year’s playoff teams, only the Rays, Yankees, and Brewers were notably bullpen-reliant. The Rays and Yankees, as advertised, have featured more playoff innings from relievers than starters, but they’re only two teams. If the Brewers had held on to beat the Nationals in the wild-card game, one of the game’s most bullpen-oriented teams—whose starters averaged 3 1/3 innings last October—would have knocked off the most starter-centric team, and that alone could have shifted the numbers enough that we wouldn’t be talking about this.

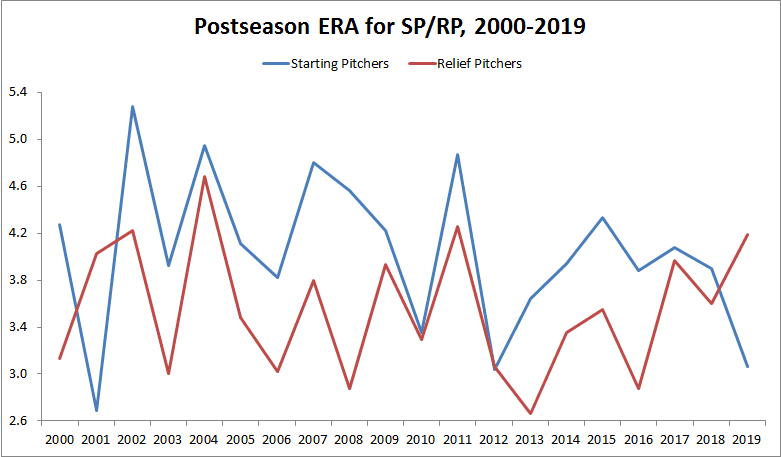

Although Mike Shildt’s slow hooks may have made things more difficult for a Cardinals team that was struggling to score, it’s hard to argue that trusting starters has hurt teams on the whole this month. Thus far, postseason starters have recorded a collective 3.06 ERA, compared to 4.19 for relievers. That sort of split is unusual.

This is only the third time in the past 20 postseasons in which starters have outpitched relievers on an inning-per-inning basis. The last time was in 2012, when starters and relievers were separated by only 0.02 runs per nine innings. The only previous postseason in the sample when starters outpitched relievers was 2001, when Randy Johnson and Curt Schilling combined for 88 1/3 innings of 1.32 ERA ball in Arizona’s rotation.

To some extent, that split mirrors an oddity from this regular season, in which relievers barely outperformed starters in ERA (4.46 vs. 4.54) and posted identical 4.51 FIPs. The shrinking starter-reliever gap was the subject of several articles, which advanced a host of possible explanations: the dilution of reliever talent as bullpens pitched more innings; the reduced demands on starters as fewer of them pitched deep into games; the spread of openers; more blowouts and lopsided matchups leading to more mop-up innings in the pen. Whatever combination of factors yielded those similar stats, the upshot is that fewer teams boasted bullpens whose performance far outstripped their rotations’. In 2017, six of the 10 playoff teams allowed a bullpen OPS that was more than 5 percent lower than their overall OPS allowed. In 2019, only the Cardinals did. As a result, fewer teams may have been tempted to ride their relievers hard when the playoffs arrived.

The last likely cause of this postseason starter resurgence is October’s other big surprise: the dejuiced ball. A few of this year’s playoff teams are powered by great rotations whose aces are excellent even in their third trips through the order, but the deadened ball that appeared this postseason has made those standout starters look even better. Consider Cole’s last outing. If the warning-track fly Didi Gregorius drove in the fifth inning on Tuesday—which Astros manager A.J. Hinch expected to leave the park—had in fact flown over the fence for a three-run homer that put Houston behind, Cole may have been pulled after 89 pitches instead of 112. There’s no reason to think starters would benefit more than relievers from the dejuicing on a per-inning basis, but they might be left in longer.

There’s no telling how the ball will behave next October, and a different collection of playoff teams may bring bullpens back into vogue. The times-through-the-order effect isn’t going away, so it’s safer to bet on this being a blip than the beginning of a lasting turnaround. However fleeting it may be, though, this October has turned back the bullpenning clock, granting a stay of execution to the workhorse starter. Historically, the starting pitcher has been baseball’s protagonist, the lone constant fans can follow throughout a game. It’s nice to have him back, for as long as this respite lasts. Old-school duels are dying out, but the battle for October innings isn’t over yet.