Across 16 seasons in the majors, Larry Bowa was a five-time All-Star, two-time Gold Glove winner, and World Series champion for the 1980 Phillies. He’s enshrined on Philadelphia’s Wall of Fame. He ranks among the most prolific defensive shortstops ever. He also hit just 15 home runs in his career; no other player in MLB history with so many plate appearances has fewer than 28.

Now a senior adviser to the Phillies’ general manager, Bowa laughs about how that career total compares with modern shortstops’ power. “They do that in a month!” he exclaims.

He’s exaggerating a bit, but the sentiment is just right. Players at the shortstop position hit 571 home runs last season, the most in history, after they’d set the record in 2017, and in 2016 before that. Those tallies are just one piece of evidence of a broad change to the position’s profile: Shortstops across the league are sluggers now, or, at the very least, they’re no longer the offensive black holes they resembled in years past.

“I think when my dad played,” says touted Toronto shortstop prospect Bo Bichette, son of ’90s outfielder Dante, “it was more like, you need to be able to field, and if you can’t hit we’ll live with it. Nowadays, you gotta be able to hit, and if you can’t field, you know, we’ll figure it out.”

The league has seen cycles of increased shortstop offense before, from the post–World War II era of Vern Stephens and Lou Boudreau to the late-’90s run of Alex Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, and others. But never have shortstops collectively hit so well or for so much power as they have over the past few seasons.

This dramatic shift reflects a number of trends that define baseball in 2019 and impart changes to the sport’s aesthetics, strategy, and player pool. The most extreme effects, though, come at shortstop, where the infield position long glamorized for its defense is in the middle of an offensive makeover.

Besides specialized roles like the designated hitter and relief pitcher, shortstop was the last baseball position invented. The early ball was soft and so light that it couldn’t be thrown even 200 feet, so in 1849 or 1850, Daniel “Doc” Adams, an early president of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, added a player whose job was to relay throws from the outfield. The idea “was not so much to add a fourth infielder as to add a fourth outfielder,” says John Thorn, MLB’s official historian—making the position the equivalent of the short fielder, or rover, in softball.

As the young sport evolved, Adams helped invent a more tightly wound ball that could travel farther in the air, and, even as shortstops drifted closer to the plate, early pioneers like Dickey Pearce and George Wright furthered the position’s defensive reputation. The latter—a Hall of Famer who played in the nascent National League in the 1870s and ’80s—“had a fantastic throwing arm,” Thorn says, “and was the marvel of all of his peers because he was making plays at shortstop that no one had ever seen before.”

Wright produced baseball’s first Web Gems, then, and besides the odd, offensively oriented exception of a Honus Wagner here and an Ernie Banks there, players at the position for the next century-plus fit that mold. For much of baseball history, teams maintained regimented position characteristics, and the shortstop’s role was clear: They were small and could handle grounders, and they reserved the practice of hitting for their teammates at more offensive positions.

Nowadays, you gotta be able to hit, and if you can’t field, you know, we’ll figure it out.Bo Bichette, Toronto Blue Jays shortstop prospect

Bowa, who retired with more than 2,000 career hits but just a 71 OPS+—meaning he hit 29 percent worse than the average for his era—says his favorite player growing up was Luis Aparicio, the slick-fielding shortstop for the White Sox, Orioles, and Red Sox who reached the Hall of Fame despite a career 82 OPS+. That performance makes Aparicio the worst-hitting non-pitcher in Cooperstown, tied with fellow shortstop Rabbit Maranville—not that those shortstops or their clubs minded. “It was ‘make sure you make all the plays, and whatever you hit is icing on the cake.’ We had guys at the corners who hit home runs,” Bowa says. “That’s the last thing on my mind, is my bat.”

Today’s game, by comparison, is coated in icing, via the sweet swings of Francisco Lindor, Carlos Correa, and more. Across a host of hitting statistics, shortstops have been at or near historic highs in the past three years. These numbers reflect shortstop performance relative to the overall league environment, too, so it’s not just that shortstops in recent seasons hit for immense power because of the overall power spike; they’re going above and beyond by improving more than players at other positions.

This chart shows the relative yearly rank of shortstop performance since 1925 (which is as far back as Baseball-Reference has batting data split by position). So for instance, shortstops as a group enjoyed their best-ever RBI season relative to the league in 2018, their second-best RBI season in 2016, and their third-best RBI season in 2017.

Yearly Shortstop Rank, 1925–2018

Other power-adjacent numbers approach historical highs as well, showing that managers have accounted for this trend. Shortstops collected their second-highest-ever percentage of intentional walks in 2018, for instance, and they took 15 percent of their plate appearances in the no. 3 or 4 spots in the lineup—their highest such share since 1949, and their third-highest ever.

Their overall value has followed suit. Players who featured at shortstop in at least a quarter of their games combined for more than 90 wins above replacement last season, according to FanGraphs’ version of WAR; before 2016, they’d never even reached 80 as a group. And that performance came with the Dodgers’ Corey Seager, the third-place finisher for 2016’s NL MVP award, missing most of the season due to elbow surgery, and Astros star Correa hitting like an average player instead of an MVP candidate while dealing with injuries of his own.

The rise in offensive production from shortstop extends well beyond stars like Seager and Correa. The middle and bottom tiers of shortstops have in fact improved by more, relative to past eras, than the top rung, lifting the entire position’s numbers in turn.

The top third of shortstops with at least 400 plate appearances averaged a 121 OPS+ over the past three years—an impressive number, but one that’s been exceeded in five previous three-year stretches since 1925. Yet the middle third of shortstops averaged a 97 OPS+ from 2016–18, the highest ever for that group. And the bottom third of shortstops averaged a 77 OPS+ in that span, also the highest such mark. (To better reflect meaningful change at the position and avoid overreacting to one-off flukes, this graph shows the average of each rolling three-year period.)

Nearly half of everyday shortstops over the past three seasons have produced at an average offensive clip or better; throughout most of baseball history, that rate was closer to a quarter or a third, or even lower than that. Two decades ago, for every Rodriguez and Jeter and Nomar Garciaparra, there was a Neifi Pérez or Rey Ordóñez or Gary Disarcina muddying the position’s overall statistics. Now, Lindor and friends are producing elite numbers without much more than Alcides Escobar weighing them down.

An obvious question follows: What factors account for this across-the-board boost? The first answer is that the offensive shift stems from a defensive shift—literally.

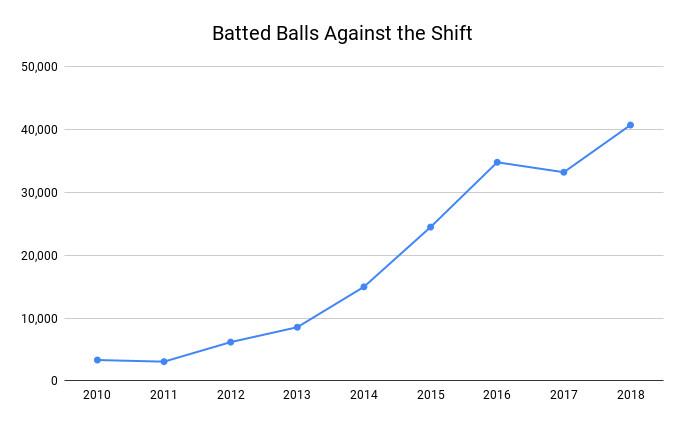

The infield shift continues to expand in popularity—after a brief plateau in 2017, its usage rose again by a large margin in 2018—and distort traditional fielder evaluations. In the past decade, shortstops have seen the number of plays they make in the position’s traditional zone drop by nearly 25 percent, while at the same time they’ve seen the number of plays they make outside that zone more than double.

Among the numerous effects this strategic trend has wrought is an increased difficulty in quantifying defensive ability, which has in turn yielded a new equilibrium as teams consider how much emphasis to place on offense versus defense. “It’s almost like the Moneyball era of defensive philosophy, where it’s like, ‘Well, fuck, we can’t measure it all that well,’” says Eric Longenhagen, FanGraphs’ lead prospect analyst. “So I think teams are a little bit more willing to punt on it.”

The measurement issue isn’t the lone culprit, though. Because of the ongoing increase in strikeouts, the numbers of both ground balls and batted balls more broadly have fallen by nearly 10 percent leaguewide in the past decade, according to tracking data from Baseball Prospectus. The decrease means that shortstops face fewer defensive chances, players who can hit home runs become even more important because they don’t require stringing together hits to score, and defensive miscues that allow an opposing runner to reach base become relatively less harmful for the same reason. “The way pitching is dominating games,” Bowa says, “the basic philosophy is, ‘Hey, if we make an error, there’s going to be 12 guys that strike out tonight, so don’t worry about it.’”

The modern game can help those now playing the position amid these strategic changes. The rise in both the shift, specifically, and analytics and defensive positioning based on data, broadly, has seemingly eased shortstop defense—at least from incredibly hard to just mostly hard.

Whereas before, shortstops might use a rough heuristic to determine their position in advance of a given at-bat—say, by shading a step or two to the hitter’s pull side—batted-ball data has made hitter-specific defensive alignments more precise. Philadelphia’s Scott Kingery, who played shortstop last season for the first time as a professional, says his club’s analytical advice simplified his learning curve. “A lot of teams are using the card where you have a specific spot where you want to stand,” he says. “You’re looking at your card and you’re like, ‘All right, I’ve got to take 10 steps this way or three steps that way.’”

To play a proper shortstop is to possess a wide range of component skills: fluid range, quick reactions, soft hands, strong arm, and so on. Superior positioning, though, helps alleviate the need for top-tier range and reaction speed, narrowing the traits necessary to succeed. Correa can’t spring into the deep hole like Ozzie Smith, but if he’s already positioned there because of Houston’s calculations, he can calmly collect a ball hit in that direction and use his rocket arm to complete the out.

So flexible is modern defensive philosophy that some players with no meaningful experience are moving to shortstop at the MLB level, in a reverse of the traditional slide down the defensive spectrum. The Cardinals’ Paul DeJong played second, third, catcher, and right field but not shortstop in his final college season at Illinois State, and he played almost exclusively as a third baseman—where he was listed upon being drafted—through his first two minor league seasons. Then he began playing short full time at Triple-A, and, through two seasons in the majors, he has not only impressed with the bat (44 career homers and a 112 OPS+) but graded as an astonishingly good defender as well. To date, he’s the only “third baseman” picked in the 2015 draft who’s debuted in the majors.

A number of other young players are either joining DeJong in this experimental effort or starting on a potential path to do so. Kingery hadn’t played more than a handful of games at shortstop since graduating high school in 2012 before slotting there 119 times for the Phillies last year; until top Reds prospect Nick Senzel suffered setbacks due to injury, he dabbled at the new position last year as Cincinnati sought a way to fit his bat in the lineup; and Longenhagen says he knows that the Rays have evaluated 2018 rookie infielder Joey Wendle, who played less than 1 percent of his career minor league innings at short, as “not just a viable defensive shortstop but potentially a very good one.”

This kind of thinking has permeated roster construction in more places than just the starting shortstop spot. Teams seek—and create—super-flexible, superutility players to field at positions they haven’t previously mastered, all to comply with contemporary roster configurations. “It’s just sort of survival of the most hitter-ish,” Longenhagen says, as clubs contort defensive alignments to stack as many potent bats as possible in their lineups.

It’s just sort of survival of the most hitter-ish.Eric Longenhagen, FanGraphs lead prospect analyst

These creative tries don’t carry a perfect success rate. Playing out of position as a rookie, Kingery managed only a 61 OPS+ last year, the worst mark for any shortstop with at least 400 plate appearances, and the Phillies upgraded by trading for All-Star shortstop Jean Segura this winter. But one setback is unlikely to slow the rate of experimentation and of teams’ blurring further defensive boundaries in the pursuit of maximum offense.

It’s unclear at this point, based on publicly available statistics, what kind of impact this jamming of untraditional pegs into an archetypal hole has on defense overall. Disentangling individual defensive performance in the infield from all the contextual changes brought on by modern tactics is a chore. Against unshifted defenses, at least, batting average on grounders and short liners into the typical shortstop area hasn’t budged over the past decade, according to data provided by Baseball Info Solutions.

Moreover, many teams that have grown more liberal with shortstop defense are those considered to possess analytical savvy. Clubs like the Rays and Cardinals have embraced heterodox shortstop tactics by considering moving unfamiliar players to the position, while the Astros and Dodgers have allowed larger shortstops with better arms than range factors to remain there instead of moving them to another infield spot. Those actions are clues, if nothing else, that smart teams think the push for more offense makes analytical sense.

Other factors have contributed to the broader trend toward shortstop power, either by themselves or in response to added defensive flexibility. For one, with the need for range diluted, shortstops can tend toward the taller and heavier side, and thus be better-suited to swing for the fences.

Bowa’s stint at short is instructive here too. He didn’t admire Luis Aparicio just for his dexterity in the field. Bowa’s childhood hero stood just 5-foot-9 and weighed 160 pounds and—along with others Bowa says he watched and learned from, like Pee Wee Reese (5-foot-10, 160 pounds) and Phil Rizzuto (5-foot-6, 150)—served as a reminder that smaller players could find a lineup spot. Bowa himself was listed at 5-foot-10 and 155 pounds in his playing days. Former Yankees utilityman Ronald Torreyes (151 pounds) is the only MLB player who weighed less in 2018.

But as Bowa neared the end of his career, a resounding development arrived and catalyzed a new kind of shortstop. On July 1, 1982, Baltimore started 6-foot-4 Cal Ripken Jr., making the young Oriole the largest everyday shortstop in league history—and the Iron Man Ripken didn’t leave the position for a single day for 14 years, winning two MVPs, a World Series, and copious other honors in that span.

Though Ripken copycats didn’t appear overnight, his unimpeachable success allowed for the possibility in the future. “The idea of A-Rod playing shortstop—people said, ‘Well, if Ripken can do it, A-Rod can do it,’” Thorn says. Ripken was the best-hitting shortstop of the ’80s. The 6-foot-3 Rodriguez was the best-hitting shortstop of the ’90s and 2000s. And the best-hitting shortstops of the 2010s are Seager (6-foot-4), Correa (6-foot-4), and Troy Tulowitzki (6-foot-3).

“Maybe my success opened up the mind-set of consideration,” Ripken told Sports on Earth in 2017. “I think that’s what you’re seeing right now. There used to be harder stereotypes about guys who have some size playing on the corners. That’s changed.” Before the mid-’90s, just two players who measured at least 6 feet and 200 pounds—Ripken and a roughly average shortstop in the ’60s named Andre Rodgers—had played half their games at shortstop in a season when they qualified for the batting title. In 2016 alone, half the league’s starting shortstops, a full 15 players, fit those criteria.

MLB players as a whole are growing larger, but the average shortstop height and weight is increasing at a faster rate than the rest of the population. “I believe it’s the evolution of the species,” Thorn says. “We’re bigger, we’re taller, we’re stronger, we’re faster.” The open-mindedness that allows for larger shortstops has permitted some to stay at the position longer as their body grows (e.g. Asdrúbal Cabrera, Jhonny Peralta) and permitted bigger, younger players to remain at the position as they ascend minor league levels. Numerous sources for this story mentioned Correa and Seager, the only 6-foot-4 men besides Ripken to make a career out of playing shortstop, as examples of players who would have automatically moved to an infield corner in previous eras.

The new de facto bounds might continue to nudge upward. A shortstop in the Pirates system, Oneil Cruz, stands 6-foot-7 and, according to an early FanGraphs report, “was literally too big to get his glove down to the ground in time to field some hot shots hit toward him.” He’d make Ripken look small—yet in the site’s top-100 writeup this winter, Cruz placed 62nd among all prospects, with the comment, “Shortstops this big don’t exist, but there’s some sentiment in the industry that Cruz will be able to stay there, especially as we enter the era of the lead-footed shortstop.”

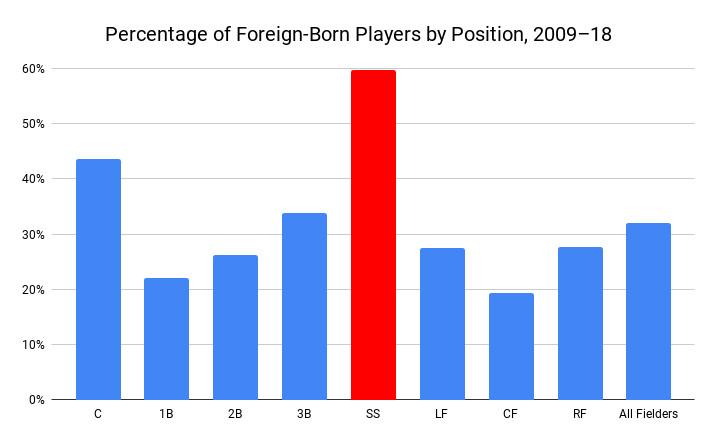

Yet another possible reason for the increase in shortstop offense concerns the influx of international players, who now constitute more than a third of all MLB regulars. Foreign-born players are not evenly distributed across the defensive spectrum, however; they’re disproportionately clumped at shortstop. More than half of shortstops with 400-plus plate appearances in recent seasons were born outside the U.S.; among other on-field positions, only catcher touches even 40 percent.

“Throughout Latin America,” says Ben Badler, who covers the international scene for Baseball America, “if a kid is right-handed growing up, he’s probably going to want to be playing shortstop.”

This isn’t a new development, necessarily, and not all foreign-born shortstops are successful at the plate. (Pérez and Ordóñez, for instance, were some of the hitters dragging down the positional average from Rodriguez’s high two decades ago.) But because the international baseball population is widening and the best foreign players seek a starting shortstop role, then it follows that the overall talent pool from which teams select their shortstops would widen in turn.

This development ties with the defensive adjustments, too, because if international players have a head start on their domestic counterparts in learning how to play shortstop, teams will leave them at the position as long as possible, or until they prove definitively that they can’t stick there full time. “There are a lot of examples you can find of guys who, when they were teenagers, when they signed or were drafted, were expected to move off the position, who just ended up surprising people,” Badler says, noting Cruz as an example.

Because of sabermetrics, I probably wouldn’t have had a chance to play.Larry Bowa, former Philadelphia Phillies shortstop

While offensive and defensive skill aren’t always tied together, at least in younger players they tend to be more united. And because shortstop is a premium—and financially lucrative—position, the most talented teenagers are incentivized to learn that role, while contextual factors allow them to collect many more repetitions and instruction at an early age than their U.S.-based counterparts. Young baseball players in countries like the Dominican Republic typically work with trainers rather than organized teams, which allows more freedom for them to practice what’s best for their future rather than what’s best for a youth team’s chances at victory. “You don’t really have second basemen in the Dominican Republic,” Badler says. “Just everybody plays shortstop. They all work out as shortstops. They work out for clubs at that position.”

With relatively good weather year-round, Badler adds, “You could work at it 12 months a year and you can always have some coach going out there to hit you a billion fungoes almost every day. As an outfielder, you can have someone hit you fly balls, but you can’t really work at it the same that a shortstop can go out there and work on his footwork and his hands and develop defensively that way.” Indeed, the premium outfield spot—center field—is the position with the lowest concentration of foreign-born players; basically all the most athletic baseball players from the region drift toward shortstop instead of center field, whereas the divide is more balanced in the U.S.

In FanGraphs’ current prospect rankings, 12 of the 17 shortstops in the top tiers were signed as international free agents rather than taken in the draft. And 11 of the 17 are at least 6 feet tall, with four standing 6-foot-3 or higher. These trend should continue for at least the medium term.

Whether the broader trend toward shortstop offense will continue is a bit more complicated. That prediction has come before, only to yield less fruitful results than anticipated. The shortstops of the late ’90s were supposed to redefine the position, yet they represented more of an outlier than the start of a revolution, the result of a particularly talented cohort rather than structural changes. As that group aged, the cycle of shortstop offense swung so low as to inspire a 2012 Associated Press piece headlined “The Day of the Big Hitting Shortstop Is on the Wane.”

In retrospect, that assessment proved premature, but it hinted at the notion that these matters ebb and flow, due to both league context and the available talent. It’s probably no coincidence that 2016, the year that started this new wave of shortstop offense, was the first full season for each of Lindor, Seager, Correa, Trevor Story, and sometimes-shortstop Javier Báez.

But again, at least for the foreseeable future, the available talent looks tantalizing and more widespread than ever before. Overall, the current crop of shortstops skews quite young. Among the dozen shortstops with the most projected plate appearances this season, per PECOTA, Elvis Andrus is the oldest at 30. Among the top two dozen, the oldest is Brandon Crawford at 32.

And beyond the known offensive forces, plenty of even younger shortstops are on their way to potential stardom. The Royals’ Adalberto Mondesi enters his age-23 season with plenty of hype after lighting up box scores in last season’s second half. San Diego’s Fernando Tatis Jr. should debut this season as the sport’s no. 2 prospect. Toronto’s Bichette, Minnesota’s Royce Lewis, and Colorado’s Brendan Rodgers—all top-15 prospects per Baseball America—should all reach the majors this summer or next. Nearly twice as many shortstops place on BA’s top-100 prospect lists now as just a decade ago, reflecting how prospect gurus understand the shifting positional landscape. Relative to prospects at other positions, young players who can ably handle themselves at short are even more important than they always have been.

Is there a limit to the caliber of athlete who can viably stick at shortstop? Sure—Miguel Sanó played there in the Dominican Republic, for instance, and nobody expected a player with his physical profile to remain at the position for long. But teams are stretching those boundaries further and further, and short of obvious cases like Sanó, public evaluators don’t know where that push will stop.

“At some point, we don’t just want the Seth Beers of the world playing shortstop, right?” Longenhagen says, referring to the powerful yet immobile Astros prospect likely destined for a DH role. “There has to be some amount of viability there, but I don’t know when that is yet. The upper bounds of my palette have already been tested, and there are definitely players who I have to force myself to consider the possibility that they can stay at short even though my gut reaction is to say no.”

Veteran infielder Cliff Pennington, now with Oakland, acknowledges that “you can maybe take a guy who doesn’t have the range” and place him at short—but that flexibility extends only so far. “You look at Lindor and Correa,” he says, “and they still go and get it pretty good, so it’s not like we’re putting guys that shouldn’t play there just because they can hit. I think the guys can do both.”

Of course, Lindor would have been a star in previous eras, too, and every team would play a Lindor at short if it had one, but shortstops who transform entire team defenses by themselves, whack 30 homers, and never stop smiling aren’t exactly commonplace. It’s when a team is forced to consider the trade-off between offense and defense that the new worldview yields different transactional demands. And in such situations, Bowa says, “the priority now is to get a guy playing short who can hit 25 to 30 home runs and he’s an average shortstop [defensively].”

Not everyone falls on this side of the divide. New Toronto manager Charlie Montoyo admits his thinking in this regard might be “old-school” but says, “I’d rather have a shortstop that can pick it and make every play. Routine play? Make it. And if you can hit, that’s great.” To wit, the Blue Jays signed just such a shortstop, Freddy Galvis, this winter, to bide time until Bichette is ready to take over.

While Galvis found a job, other glove-first shortstops like José Iglesias, Adeiny Hechavarria, and Alcides Escobar had to settle for minor league deals this winter. Bowa himself notes that if he were a young shortstop trying to start a career in 2019, “Because of sabermetrics, I probably wouldn’t have had a chance to play.”

Not without growing half a foot or boosting that home run rate, anyway. Whereas earlier this decade, the big-hitting shortstop was on the wane, now it’s the good-glove shortstop who might disappear. The sluggers are taking over, and nothing seems liable to stand in their way.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of Sports-Reference for data assistance and Katie Baker and Michael Baumann for additional reporting.