At times, the National League Championship Series looked a little like the bazaar scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark. There was Craig Counsell, brandishing his bullpen and flipping his pitchers from side to side. And there was Dave Roberts, in Game 5 and again in Game 7, calling on the conventional Clayton Kershaw and Kenley Jansen to blow the Brewers away.

But as much as the NLCS seemed like a matchup between a perennial powerhouse and an outgunned opponent who couldn’t compensate with creative techniques, the Indy analogy does a disservice to both sides. For one thing, it gives short shrift to the Brewers, who mounted much more of a fight than Indy’s opponent: Milwaukee pushed the series to a seventh game and actually outhit and outscored L.A. overall. But it also undersells the Dodgers, who in addition to boasting the NL’s second-highest payroll and highest hitting and pitching WAR this season also benefited from fancy tactics of their own.

We saw an example of what the Dodgers do differently in the fifth inning of Game 7, when Chris Taylor made a lead-preserving leap to rob Christian Yelich of what would have been a game-tying extra-base hit.

The 28-year-old Taylor started Game 7 at second base and moved to left midway through the third inning after soon-to-be-second-sacker Kike Hernández pinch hit for starting left fielder Joc Pederson against lefty reliever Josh Hader. In the celebratory seconds after Game 7, FS1’s Ken Rosenthal asked Taylor about the difficulty of switching positions midgame. “We’re so used to it now,” said Taylor, who played multiple positions in five of seven NLCS games, including three positions twice. “I don’t remember the last time I played a game at one position the whole game. We’ve changed so much that it just becomes second nature.”

The last time Taylor played one position all game was NLDS Game 3 (or September 22, if Game 3 doesn’t count because Pederson pinch hit for Taylor in the top of the ninth). That wasn’t really that long ago, but October is a hectic time, particularly if you’re roving around the field from game to game and inning to inning. Taylor is one of four Dodgers who started more than 40 games (and appeared in more than 50 games) at positions other than their primary one during the regular season, a product of what writer Joe Sheehan has dubbed the “Team Pretzel” approach. No NL team in 2018 used more players at nonpitching positions than the Dodgers’ 28, and no NL team had fewer players total at least 520 plate appearances than the Dodgers’ two. No team in the majors amassed more cumulative appearances at defensive positions than the Dodgers’ 2,335, and no team finished with fewer complete games played at defensive positions than the Dodgers’ 910. The Dodgers also generated the most or second-most games in the majors at catcher, first base, second base, left field, and center field, and they ranked in the top 30 percent of teams at every other position: fourth at pitcher, fifth at third base, sixth in right field, and tied for ninth at shortstop. Finally, no team in the majors announced more pinch-hitters than L.A.’s 362, which translates to a rate of roughly 2.2 per game.

Few teams in history have made for more diverse scorecards than these Dodgers. In 2016, The Ringer’s Rany Jazayerli formulated a metric called “Flex Score” to capture a team’s tendency to play defenders at multiple positions. Flex Score, as Rany defined it, is the cumulative count of games started by players at a position apart from their primary one, excluding DH and lumping together the three outfield spots. Taylor, for instance, made a plurality of his starts this season at shortstop, which by that definition was his primary position. But he also started 50 games in the outfield and five games at second base, giving him a Flex Score of 55. When he conceived that stat, Rany was writing about the Cubs, whose combined Flex Score of 173 that year—identical, as it turns out, to the 2018 Cubs’ total—ranks in the 98th percentile among all teams since 1908, when Retrosheet’s data on games started begins. But the 2018 Dodgers dwarf every Cubs club, tying for the fifth-highest Flex Score on record, 230. Positional fluidity can be a hallmark of a bad team, too, and no 90-win team or playoff team has ever recorded a Flex Score that high. By that definition, then, these Dodgers are the most flexible good team on record.

In a sense, though, that method underrates the current Dodgers’ versatility. What distinguishes this team isn’t just a tendency to start players at different positions from game to game; it’s also the frequency with which they rotate players within games—or, as manager Dave Roberts has borrowed a hockey term to describe it, make a “line change”—yielding both diverse scorecards and messy scorecards. If we redefine Flex Score to count not just games started at nonprimary positions, but games played at nonprimary positions (excluding pitcher), then the 2018 Dodgers vault to the top of the list of almost 3,000 major league teams going back to 1871. The NL side of this World Series will feature the most prolific group of position changers ever. (The complete list of teams and Flex Scores is here; the 2017, 2018, and 2016 Cubs rank 12th, 16th, and 23rd, respectively.)

Highest Team Flex Scores, 1871-2018

The Dodgers didn’t entirely plan this, of course. Opening Day shortstop Corey Seager played shortstop exclusively from 2016 to 2018, but after he suffered a season-ending injury in late April of this season, Taylor and Hernández split time at short until Manny Machado arrived in July. Similarly, Justin Turner’s absence until mid-May with a wrist fracture forced Logan Forsythe and Max Muncy to fill in for several weeks at the hot corner. And when a groin strain sent Turner back to the DL in late July, Machado saw some time at third, with Taylor and Hernández adding to their tallies at shortstop.

While those injuries helped L.A. finish first in flexibility, though, the Dodgers are designed to feature many moving parts. (Last year’s club tied for 34th in Flex Score on the all-time list.) Muncy and Hernández—the latter of whom spent time at every defensive position except catcher this season—were multiposition players before the Dodgers acquired them, although their bats have blossomed this season, which has made them even more useful as subs when they aren’t in the starting lineup. Bellinger, a Dodgers draftee, played first base and all three outfield positions throughout much of his minor league career, which groomed him for a flexible role. Taylor had never played outfield in either the minors or the majors before the Dodgers stuck him in center and left last season, creating a super-utility player where only a run-of-the-mill utility player previously existed.

As Taylor suggested after Game 7, the Dodgers fielders’ frequent rotations don’t seem to come at any cost to their performance. In 2013, Baseball Prospectus writer Russell Carleton studied several seasons of defensive data and found no evidence that defense degrades after players switch positions midgame. (Of course, that doesn’t mean that any player could change positions without suffering ill effects; it’s just that the players whom teams do trust to do that constitute a selective group with a very particular set of skills.) And although the samples are small, there’s no indication that the Dodgers defense, specifically, has suffered after switches this season. According to Sports Info Solutions, the range and positioning of the Dodgers defense was worth 40 defensive runs saved on the season, which was distributed fairly evenly over the course of their games: plus-9 in the first three innings, plus-16 in the middle three innings, and plus-15 from innings 7 to 9. And accounting for the difficulty of the positions they played, the four most frequent position switchers—Bellinger, Hernández, Taylor, and Muncy—rated even better after switching positions in games (a weighted average of 0.84 defensive runs saved per 1,000 innings) than they did as starters (a weighted average of 0.61 defensive runs saved per 1,000 innings).

The Dodgers’ depth and versatility positions them perfectly for the AL-brand baseball they’re about to play in games 1 and 2 (and 6 and 7, if necessary). While some NL teams have to stretch to find a desirable DH, the Dodgers have a surplus of capable candidates, including Matt Kemp against lefties and Muncy versus righties. And as the Red Sox summon new pitchers to pursue platoon advantages, the Dodgers can counter, up to a point, without leaving vacancies in the field.

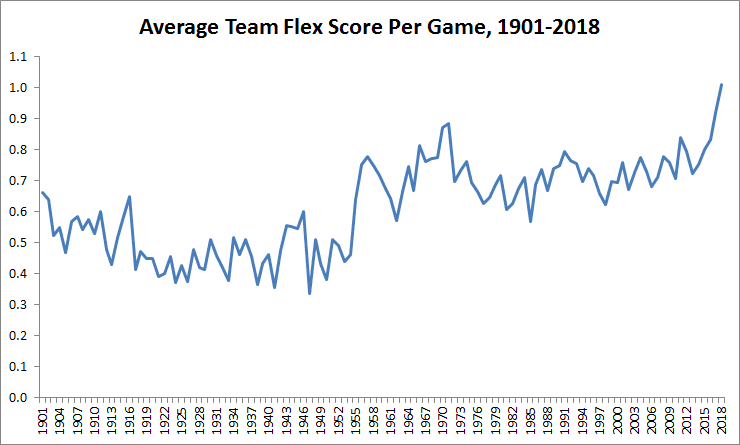

It’s a testament to Roberts that the Dodgers have embraced a style of play that requires individual players to sacrifice some playing time as well as the luxury of predictable positioning from day to day. And that buy-in—coupled with the astute acquisitions and subsequent coaching that gave Roberts rich raw material to work with—have yielded not only a major league–leading offense, but the type of roster construction that most managers covet today. The graph below shows the average team Flex Score per game in each season since the advent of the American League in 1901.

It wasn’t uncommon for teams to carry super-utility types in the decade or two preceding the DH. The highest single-season Flex Scores of all time belong to César Tovar, who posted totals of 115 and 130, respectively, for the 1967 and 1968 Twins. Tovar’s versatility was so prized (and unprecedented) that he received MVP votes for five consecutive seasons from 1967 to 1971, and he hit well over that span, particularly for a player who could, and did, play every defensive position. But in the post-Tovar era, the super-utility player languished, notwithstanding the odd Bill Almon, José Oquendo, or Tony Phillips. In recent years, though, baseball has welcomed “a new, potent generation of super-utility players,” as Rob Neyer notes in his new book, Power Ball. That’s partly because Joe Maddon and his super-utility toy in Tampa Bay and Chicago, Ben Zobrist, have helped open teams’ eyes to the value of versatility—not just among good-glove, no-hit players, but among all-around stars such as Zobrist, Kris Bryant, and Bellinger. “Maddon obviously wasn’t the only manager who saw the value in a super-utility player,” Neyer writes. “But he might have been the first since [Tony] La Russa to make a real habit of them.”

Although Zobrist’s ascendance as a sabermetric cause célèbre helped establish a new beauty ideal for batters, it likely isn’t an accident that he and his ilk have arisen right now. In an era of rampant bullpenning, positional flexibility is more and more advantageous to teams, who still have the same number of roster spots to distribute. As pitching staffs have swallowed more than half of the openings on the average active roster, nonpitchers have had to demonstrate versatility to justify their jobs. Thus, as pitchers’ roles have grown more specialized by the season, position players have increasingly carried more gloves. At a time when eight-man pens are predominant and nine-man pens aren’t unheard of, Neyer writes, “A manager’s second-favorite security blanket might be the super-utility player. … If you’ve got a player who’s at least semicompetent at two or three infield positions and can handle the outfield chores without embarrassing himself … well, you’ve just made the manager’s job quite a lot easier.”

As bullpens have expanded, two other trends have made Dodgers-style flexibility feasible. Aggressive defensive shifting and optimized positioning have helped managers ameliorate the flaws of their defenders, even as rising strikeout rates—which Dodgers pitchers have helped drive this season by leading the NL—have led to fewer balls in play, decreasing the cost of surrendering range. As a result, modern major leaguers no longer need to be naturals to play particular positions. (Hence the recent rash of writing about “positionless baseball.”) Put all of these trends together, and it’s no surprise to see that the average team Flex Score reached an all-time high in 2018, topping the previous record set in … 2017. The Dodgers are the embodiment of a period of unparalleled positional fluidity.

This series represents a matchup between two teams that are much more evenly matched than one would conclude from their 16-win gap in regular-season records and the polar-opposite routes they took to reach this point, both within their divisions—one a walkover, one a fight to a tiebreaker—and in the postseason so far. By run differential, the regular-season Red Sox and Dodgers finished second and third behind Houston, and the Dodgers, bolstered by Turner and Machado, led all teams by Pythagorean record in the season’s second half. By BaseRuns record, the Dodgers (who underperformed by nine wins) actually outpaced the Red Sox (who overperformed by the same margin). And by projected strength of their October rosters, there’s little daylight between the two. The Dodgers are more dangerous than they look. And that’s partly because they rarely look the same for long.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of Baseball-Reference, Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus, and Alex Vigderman of Sports Info Solutions for research assistance.