With a historically dull division-series round behind it, October baseball has belatedly gotten good. Like a sport described by Stefon, the championship series round has had everything. There’s an Astros heel who’s trolling opposing pitchers and delivering cocky quotes and a Dodgers heel who’s getting fined for tripping, failing to hustle (but still hustling sometimes), and being called a “motherfucker” by a likely MVP. There’s a youthful-looking manager bringing back a century-old deception. There are two teetering closers who’ve made nearly every outing unbearable and riveting. There are incredible catches, Puig GIFs, and both one of the worst and one of the best postseason starts of Clayton Kershaw’s career. A mysterious man named Kyle did something suspicious with signs, and paranoid teams are pioneering new ways to signal for a pitch. And the game’s most recognizable umpire went from body-blocking an errant throw to ruling fan interference on what would have been a Houston homer, putting himself in the running for Red Sox series MVP.

All of which makes it easier not to notice that October baseball is, in many ways, the worst brand of baseball we watch all year. The playoffs take every regular-season on-field trend that makes fans fear for the game’s future and ask, “Hey, why don’t we do more of that?” For fans who are already tightly tethered to the sport, playoff baseball is the best because the stakes are so much higher than they can be during the regular season, when each game constitutes a tiny fraction of a lengthy serialized story. But at the one time of year when a largely regional sport draws national attention, baseball keeps putting its most unsightly self in front of potential new fans. Let’s count the ways in which playoff baseball looks like a distorted, dystopian vision of the baseball we watch for most of the year—and a warning of where the game is going unless the league intervenes.

Game Length

ALCS Game 4 was a phenomenal fight between baseball’s best two teams full of lost leads, web gems, and close calls. It was also four hours and 33 minutes long, which made it the second-longest nine-inning game in playoff history—the longest, naturally, was played last year—and tied for the fourth-longest nine-inning game ever, regular season included. The average playoff game this season has taken 3:45 to complete, a new record even by October’s bloated standards.

Part of the problem, as always, is longer commercials. This postseason, the time between innings—or, more precisely, the time between the last pitch of one inning and the first pitch of the next—has been about 40 seconds longer than it was during the regular season.

Contrary to common belief, the length of ads is not the primary driver of inflated game times. There are at most 17 between-inning breaks during a regulation-length game, and at roughly 40 extra seconds per break, the total time increase from commercials comes to a little more than 11 minutes. Yet the time gap between 2018’s regular-season and postseason games has grown to more than 40 minutes, even though the difference in time between innings hasn’t increased. Rampant capitalism accounts for only a little more than a quarter of the extra time baseball fans spend stuck to their couches at this time of year, which means that much of the gap must stem from an even more insidious development: an ever-slowing pace of play.

Game Pace

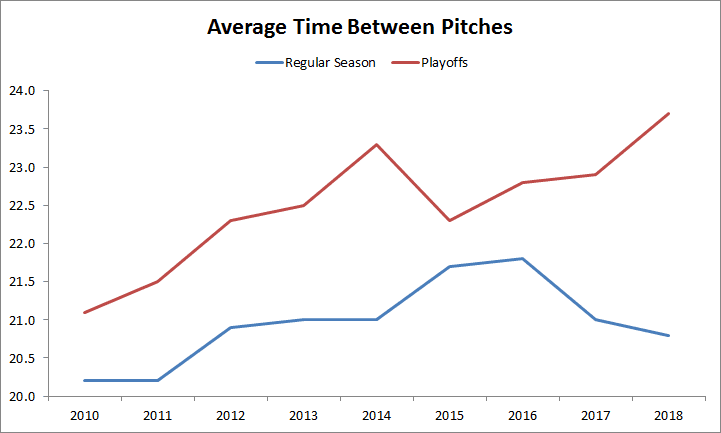

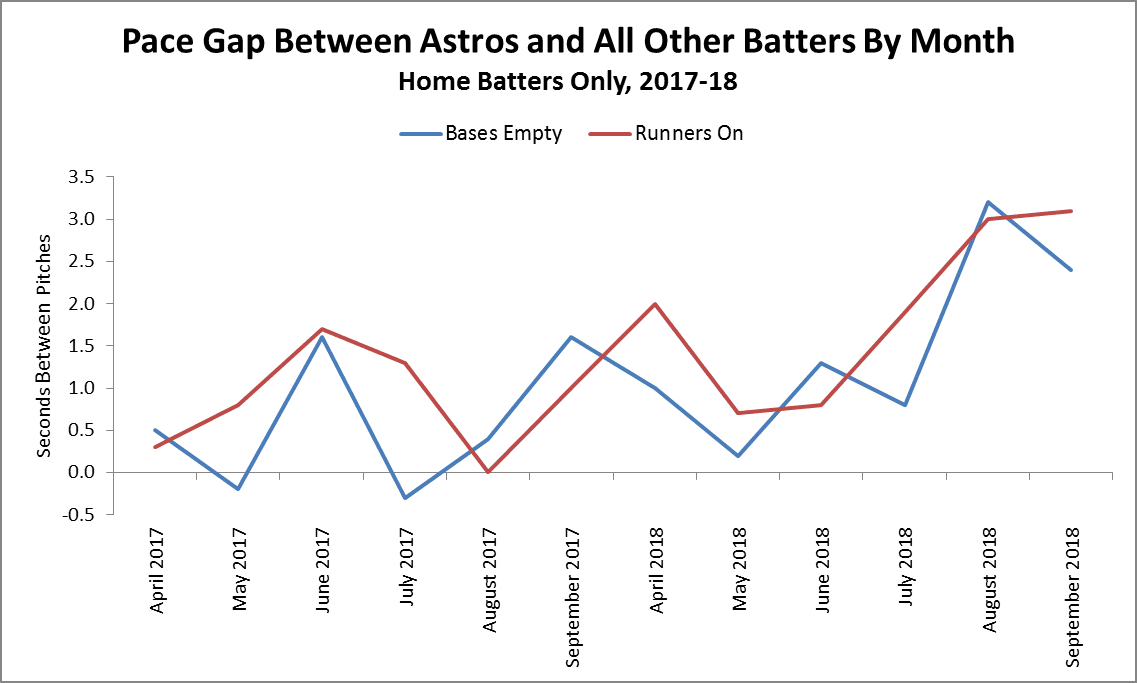

Yes, notorious slowpoke pitcher Pedro Báez has pitched in these playoffs, and two of the only three regular relievers slower than Báez this season (Brad Hand and Joe Kelly) have appeared in this postseason too. But the leaguewide slowdown isn’t confined to a few pitchers. According to data from Pitch Info—which filters out long delays attributable to injuries, replay reviews, mound conferences, or benches clearing because someone is mad at Manny Machado—the typical time between pitches this postseason has climbed to 23.8 seconds, eclipsing any previous postseason or regular season.

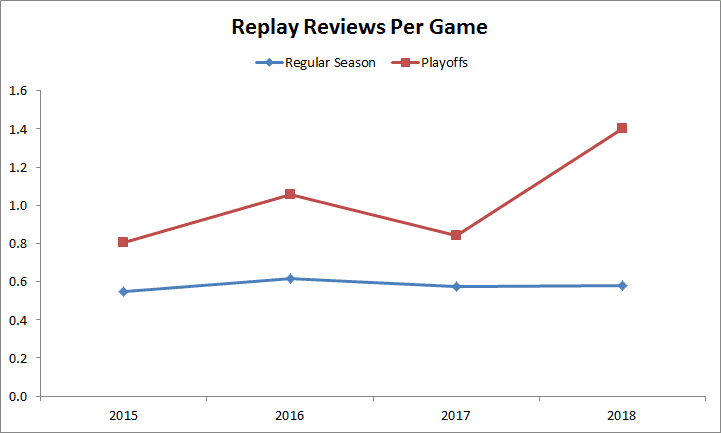

Those extra seconds between each of the hundreds of pitches per game—partly a product of the heightened importance of each pitch, but probably also a by-product of growing concerns about sign-stealing—lead to a lot of dead air. And while we don’t have data on non-pitching-change mound visits this postseason, we know that they have tended to tick up in October, rising from 4.2 and 4.3 per game during the 2016 and 2017 regular seasons, respectively, to 6.5 and 6.7 during those postseasons. While visits are theoretically limited today, substitutions (which offer a free opportunity to meet) are frequent enough in October that player congregations haven’t seemed to slow down. And neither has the rate of replay reviews, another time-waster that’s always more prevalent in October but has ticked up significantly this postseason even relative to previous years (insert Angel Hernandez joke here).

Bullpenning and Pitching Changes

Even without counting openers as the relievers they really are, bullpens have pitched more than half (50.3 percent) of playoff innings this season, a dramatic increase from their record 40.1 percent during the regular season and then-record 46.5 percent last postseason. That rapid evolution, led by the rotation-challenged Brewers’ 64.8 percent (!) preference for the pen, has caused a bit of a bullpenning backlash based on the disappearance of starters, who used to play a central role in the narrative of each game. But there’s another reason to be miffed about bullpenning: It brings many more pitching changes.

This year’s playoff teams have combined to average almost nine pitching changes per game, with the reliever parade sometimes starting in the first inning. Granted, some of those changes occur during breaks between innings when we’re already captives to the TV. But many others add additional unwanted interruptions to the plod of play.

Stuff

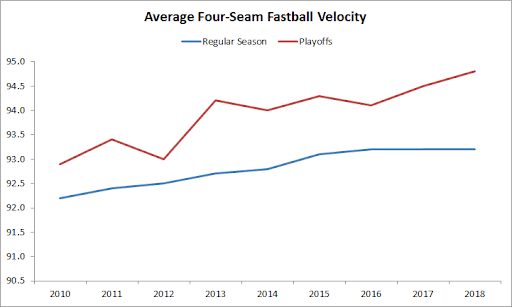

Another consequence of the October rise of relievers is a corresponding increase in fastball velocity. This postseason, pitchers are averaging 94.8 mph when they throw four-seam fastballs, another all-time high.

As a group, relievers throw harder than starters, and because relievers are throwing a higher proportion of playoff innings, starters, in turn, can feel free to air it out, knowing that they won’t need to go deep into games. And because pitchers understand the importance of each playoff pitch, they’re more likely to throw as hard as they can on every delivery than they would when the season isn’t always on the line. The playoffs also admit more hard throwers to begin with, because playoff teams tend to be good teams, and good teams tend to employ good pitchers, and good pitchers tend to throw hard.

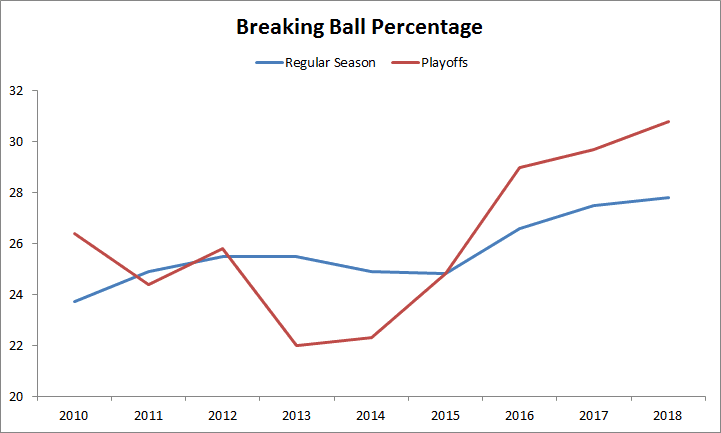

Even though fastballs have never been more blistering, playoff pitchers are throwing more breaking balls, another amplification of a regular-season trend: This is the first year on record in which whiff-happy pitchers collectively threw more sliders than sinkers. Not only have postseason pitchers gone to their breaking balls more often than ever this month, but they’ve also thrown more breakers than ever relative to the regular-season standard.

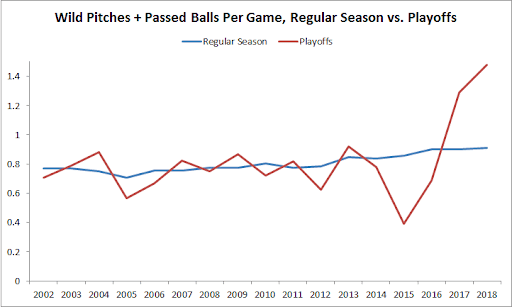

Combine faster fastballs, more breaking balls, more pitchers per game, and increasingly complex systems for relaying signs, and you have a recipe for more balls bouncing to the backstop, whether because catchers are getting crossed up or because they just can’t get their gloves on the ball. Pitchers threw more wild pitches per game during the 2018 regular season than in any season since the 19th century, and as FanGraphs’ Craig Edwards observed, the rate of passed balls and wild pitches per postseason game has skyrocketed since 2016. The normally reliable Yasmani Grandal has looked like a butcher behind the plate in the NLCS, but he isn’t the only catcher having a hard time blocking balls.

True Outcomes

If playoff pitchers are becoming more difficult to catch, it stands to reason that they would also be harder to hit. And they are: Hitters have struck out in 23.8 percent of their postseason plate appearances, up from 22.3 percent during the regular season. If we lump together the three true outcomes (strikeouts, walks, and homers), as well as hit by pitches—another non-ball-in-play occurrence that has reached a record post-19th-century high—we find that only once since 2010 has the postseason produced more balls in play per plate appearance than the rest of the season.

Similarly, only once since 2010 have playoff hitters outhit regular-season hitters, as good pitching, good defense, and cold weather combine to suppress scoring despite the presence of more dangerous hitters on the whole.

To recap: Playoff baseball is significantly longer and slower-paced than regular-season baseball, with more mind-numbing delays, fewer balls in play, and less scoring. Add in later start times, and the playoffs are actively contributing to the perception that baseball is a boring slog that only an old could enjoy.

None of these threats will go away without intervention. Most of the developments documented above have been building for decades, but both the league and the still-powerful players association have long hesitated to tinker with the working of the sport. In October, teams collectively take existing trends to extremes, both because playoff clubs often embody the latest and greatest ways to be good at the game and because the postseason schedule permits much more aggressive strategies than the six-month marathon that precedes it. To a greater degree than the other major sports, baseball morphs into a fundamentally different game during its most important period. But it’s not so different that we should ignore what it’s trying to tell us about what baseball’s future will look like if these trends are left unchecked. It was seen in some quarters as a sign of the impending apocalypse that this regular season featured more strikeouts than hits for the first time, but that’s been the norm in October since 2015. The rest of the season just took some time to catch up.

That the playoffs remain so compelling is a testament to the suspense of short series and the connection that fans forge with their teams over many months. But MLB can’t count on every viewer having binged the whole season before October begins. If the league wants its product to do more than attract true believers, the playoffs have to be friendlier to channel-flippers for whom four-hour games are a few innings too far.

Thanks to Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus and Craig Edwards of FanGraphs for research assistance. All stats updated through Wednesday’s games.