The Bittersweet Saga of an Aspiring Esport’s Huge Ambition and Brief Life

Juxtaposed with the mainstream success of the Overwatch League, the troubled development, belated arrival, and untimely end of video game ‘Gigantic’ show how hard it is to make a good game or a viable esport—and, having made one, how hard it is to convince people to play u003cemu003ethat u003c/emu003eone instead of something elseOn Friday, July 27, a near-capacity crowd of 11,000 packed the Barclays Center in Brooklyn for the first day of the Overwatch League Grand Finals. The two-day event, which pitted the eventually victorious London Spitfire against the Philadelphia Fusion, concluded the inaugural season of the pioneering, international league formed by Blizzard Entertainment, the revered video game developer that released Overwatch—a six-on-six, objective-based, first-person shooter—in 2016. From the floor, where the Philly fans’ thundersticks crashed, the esports display was an audiovisual spectacle akin to the concerts that often fill the same space: Bright lights and loud commentary banished shadows and silence, and massive video screens loomed over the crowd, magnifying the young competitors who sat on the stage, almost hidden behind their computers. The OWL’s big finish showcased the fledgling league’s vision of a game that could cross over into mainstream culture: DJ Khaled performed, Jon Bon Jovi and multiple Brooklyn Nets attended, and Spitfire supporter (and former OWL endorser) Serena Williams watched from afar, along with more than 860,000 other people worldwide who streamed the action online or tuned in to ESPN, which made the OWL’s Grand Finals the first live competitive gaming event ever to air on the network in prime time.

Just as the Overwatch League was enjoying its moment of triumph, an analogous game that once had hoped to be a breakthrough success was saying goodbye. On a much quieter corner of Twitch, devoted fans, accomplished players, and longtime streamers assembled to send off Gigantic, an online shooter that had lost its war with Overwatch and every other competitor in an increasingly crowded multiplayer market. Gigantic was announced before Overwatch, but by the time it was ready for a full release, Overwatch was already almost 14 months old. In January, Gigantic’s publisher, Perfect World Entertainment, which had already laid off most of its developer Motiga’s staff the previous November, announced that the game was about to be over: Its servers would be going offline for good on July 31, giving it six months before doomsday. Gigantic’s official Twitch channel went dark soon after that January notice, but it flickered back into being on the 27th for one last celebration of life, days before the plug would be pulled. “We won’t be able to play the game come Tuesday, but everybody in the community is still going to be here,” quavery-voiced community manager Jared Browar, who officially interfaced with the fans first for Motiga and later for Perfect World, said in the last seconds of the stream. The video has only 1,200 viewers to date.

Gigantic was, in some ways, a success. At the most basic level, it came out, which is never guaranteed in game development and at times looked like a long shot in Gigantic’s case. In a market crowded with copycats, it developed a unique art style and a pioneering approach to gameplay. And it was well received both by reviewers and by many of the people who played it, some of whom became dedicated fans and advocates.

It’s a tragic story of missed opportunities.Joseph Pikop, Gigantic’s lead character artist

Even so, it failed to find a big enough audience to ensure its survival, and a little more than a year after its release on Steam, Windows 10, and Xbox One in July 2017, it’s now completely unplayable, wiped away so thoroughly that even the announcement of its impending demise is accessible only via an archived page. Juxtaposed with the mainstream success of the Overwatch League, Gigantic’s troubled development, belated arrival, and untimely end make for a bittersweet saga about how hard it is to make a good game or a viable esport—and, having made one, how hard it is to convince people to play that one instead of something else. Gigantic’s lead character artist, Joseph Pikop, was one of Motiga’s first recruits, long before the layoffs, and like many who made the game, he wonders whether it might have had a happier ending given different decisions and better luck. “It’s a tragic story,” he says, “of missed opportunities.”

The company that created Gigantic didn’t start its life aspiring to make a multiplayer shooter for PC and consoles. Initially, Motiga’s mission was all about mobile. Company cofounders Chris Chung and Rick Lambright were industry veterans who wanted to start their own studio. Chung, who became Motiga’s CEO and served in that role throughout Gigantic’s laborious birth, had been a business manager at ArenaNet when that company shipped its hit massively multiplayer online (MMO) game, Guild Wars. Following a promotion, he joined another MMO developer as its chief strategy officer, but he lasted for less than a year in that role before leaving to strike out on his own in the summer of 2010. “After having run a large publishing organization, I missed the days when there were a small group of people creating something new,” he says via email. The Bellevue, Washington–based Motiga was a way to bring back those days.

When Apple launched the iPad in April 2010, Chung saw its potential as a gaming platform. Although plenty of companies were making games for iOS, he thought there was an opportunity to create a set of technologies that would allow developers to quickly and easily make multiplayer games that could communicate in real time on all major mobile platforms. Hence Motiga (Mobile Online Touch Interface Games) and its mobile server technology, which it called MICE (Motiga Infinite Context Engine). Motiga wanted a new game to showcase its tech, so it settled on a tower defense title called The LeftOvers, which was inspired by Lord of the Flies.

Motiga, which was still small, outsourced the game’s development to an external company, Tinfoil Fez. But the outside company’s personnel “weren’t necessarily passionate,” Chung says, and even he saw mobile gaming more as a business opportunity than a personal passion. “I remember coming home from work and playing online games on my PC,” he says. The LeftOvers wasn’t successful, so in late 2011, Chung decided that Motiga would pivot to developing an online game for PC. At that point, he hired some ArenaNet veterans who had an idea for an MMO-style game that would feature staples of that genre, such as dungeon raids and player vs. player (PvP) combat. Successful raids against computer opponents would yield loot and gear that would empower players to take on more challenging human adversaries in the PvP areas. In many MMOs, excelling at raiding and PvP requires cooperation and intimidating time commitments, but Motiga aimed to change that. “The idea was to make the experiences more casual and accessible while maintaining the fun,” Chung says.

The concept for that game, which was code-named “Raid,” would undergo a number of changes on the road to release as Gigantic, the project to which Motiga devoted all its time and resources for the remainder of the studio’s existence. Although Motiga secured funding from a number of angel investors, Chung says he soon realized that “the scope of what we needed to create was going to require a lot more capital than I imagined. So we shelved the raid aspect of the game and decided to focus first on creating a PvP experience.”

At first, the PvP part of the game was a five-on-five affair in which there was one neutral monster, or “Guardian”—along the lines of the original raid bosses—that had to be defeated in order to take over enemy territory. There were no “heroes,” or characters with distinct personalities and predetermined powers or appearances—only stock models that the player could customize. Chung soon decided to switch to the hero-based model that had worked so well for MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena) games like League of Legends and Dota.

But in early 2013, development ran into trouble: As Chung recalls, “the game was just not fun and didn’t have a clear vision.” He decided to bring on a lead designer to shepherd the game to completion, and he chose James Phinney, a former Blizzard and ArenaNet designer who had previously served as the lead designer of real-time-strategy classic StarCraft, as well as Guild Wars. “[James] quickly brought significant changes to the design that everyone in the studio believed was the right direction,” Chung says. Vinod Rams, who joined Motiga early on as a senior concept artist, says, “That’s when the game truly became Gigantic. Two giant Guardians, 5v5 crazy combat, control points, and summonable creatures.” Players could kill opponents, capture control points, and protect them with summoned beasts to power up their Guardian, then attack the opposing squad’s Guardian as their own Guardian exposed its counterpart’s weak point.

Rams and his artist colleagues were just as responsible for forging Gigantic’s identity as game designers like Phinney. Asked what set the game apart from other online titles, Chung credits its art style. “It had a unique look that stood out in the marketplace,” he says. Like Chung, many of Gigantic’s artists were eager to work without the strictures of larger studios and more regimented hierarchies. Rather than appoint an art director and defer to authority, the team worked democratically, referring when necessary to a cocreated 30-plus-page PowerPoint file that laid out the department’s principles and helped resolve disputes.

Some of the artists had worked on the realistic-looking Guild Wars, while Rams was coming from contributing to the gritty Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor. Gigantic gave the team an opportunity to design something brighter and more stylized. Rams recalls, “There’s been so many other times where I get told to make … whatever I’m drawing, usually a character or a creature, less cartoony. And then Gigantic, I remember my first week at Motiga, I put in a bunch of sketches and they all looked at them, and some of the guys there … were just like, ‘It’s cool, but I want it to be way more stylized.’” That was what Rams wanted to hear.

The art team drew on a broad range of influences, including Saturday-morning cartoons, ’80s pop stars, mangas and graphic novels, Studio Ghibli animation, and the Valve shooter Team Fortress 2. The result, Rams adds, is that Gigantic’s heroes have a look that’s all their own. “They are extreme, and there’s a sense of humor to them, and the shapes are really interesting, and they’re not what you’d want to call lazy character design, where it’s just like, stock hot guy or stock hot girl with cool gun, make her blue, and she’s done.”

Motiga’s determination to not model Gigantic’s art style on that of any other IP extended to the company’s gameplay-design decisions, both for better and for worse. “We were really trying to create something fresh and different,” says former Motiga lead designer Carter McBee. As part of that process, the designers consciously avoided labeling the game as belonging to any one genre. Whereas some developers borrow familiar mechanics (which can’t be copyrighted) from other games and put their own spin on a proven formula, the Gigantic crew tried to start fresh with a mode that was unique to their game. “We were evaluating potential features and gameplay changes against Gigantic’s gameplay rather than against other games on the market,” McBee says.

There weren’t really any games you could point to and say, ‘Gigantic is just like that game!’ which was intentional, but ended up being both a blessing and a curse when it came to marketing and the onboarding of new players.Carter McBee, former Motiga lead designer

That philosophy sometimes worked to Gigantic’s advantage: In an industry prone to copycatism, Motiga’s game was, in theory, capable of staking out its own corner rather than drafting in the wake of another breakthrough title. The downside lay in the lack of a simple pitch to potential players and investors—this game you know meets that game you know, or this game plus a single, intriguing addition. “It blurred the lines of multiple different genres,” McBee says. “There weren’t really any games you could point to and say, ‘Gigantic is just like that game!’ which was intentional, but ended up being both a blessing and a curse when it came to marketing and the onboarding of new players.”

Pikop was one of the Motigans who would talk to the press about Gigantic or show the game to crowds at conventions, so he regularly ran into the problem of convincing people to try it before they lost interest or a competing title caught their eye. “I think it’s really easy to be reductive, when it comes to, ‘What is the game? Tell me what the game is,’” he says. When he encountered confusion, he often found that the best tactic was to get people to play while he walked them through it. Although he acknowledges that the inability to boil the game down to a blurb or a sound bite was a problem Motiga never fully solved, he says he wouldn’t have done things any differently. “I know other people would’ve said, ‘Oh, let’s just make it a shooter. … Let’s just make it an objective-based team-play game,’” he says. “I was never interested in doing that. I was always interested in coming up with the thing that [would make people say], ‘Oh, it’s Gigantic. This is special.’”

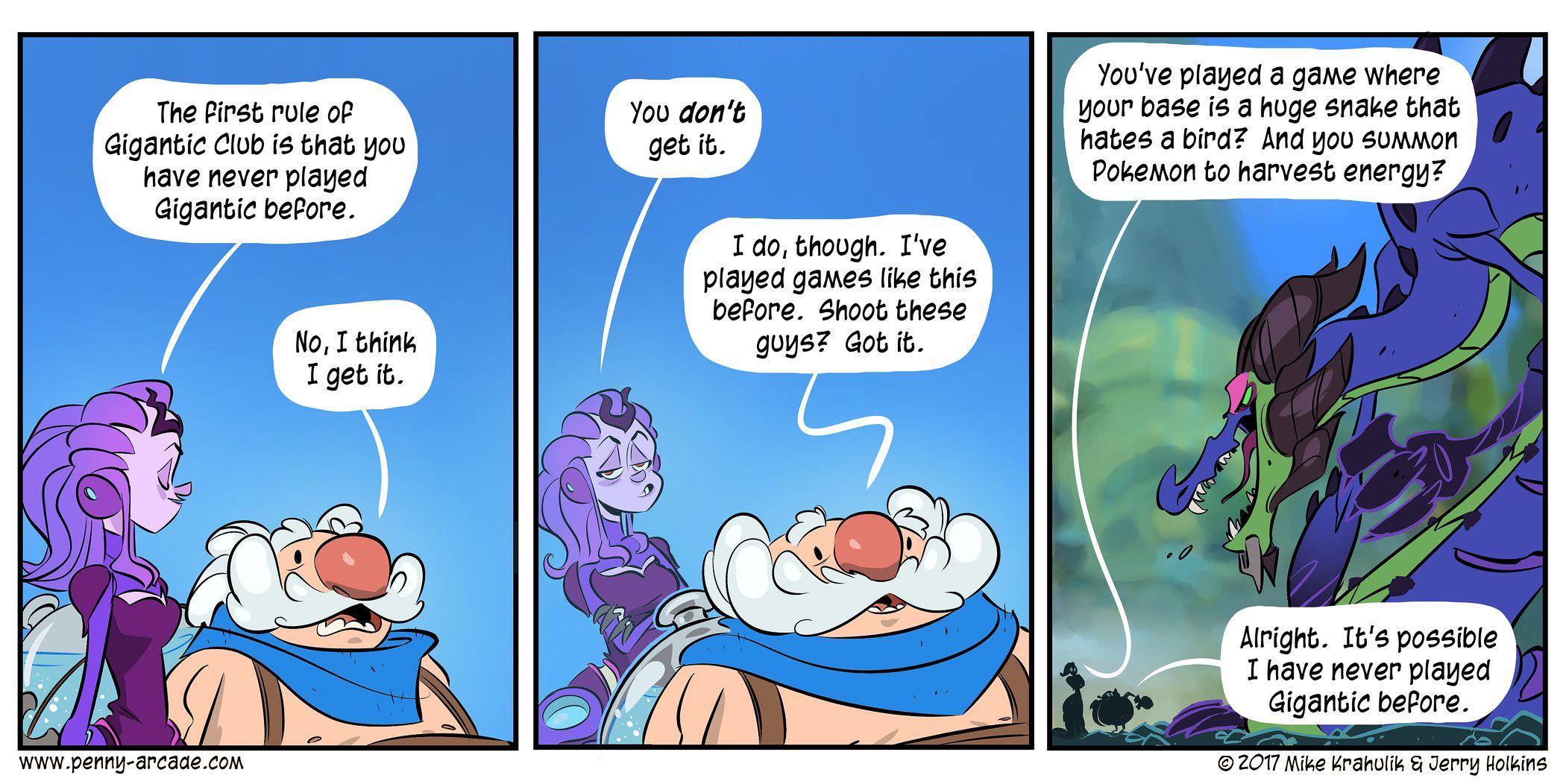

Although Rams also prized the game’s unique potpourri of playstyles, he regrets the “clarity issues”—from user-interface issues to particle effects with the potential to be visually distracting—that prevented people from experiencing Gigantic at its best. “Showing the game to brand-new people that just aren’t into these kinds of games, it was overwhelming,” he says, adding, “Even hardcore gamers, it still took them time to really figure out what was happening. It wasn’t as intuitive as we hoped.” The popular geek-culture webcomic Penny Arcade captured that daring but daunting structure in a February 2017 comic. “I know that [Gigantic] totally looks like something we already have a mental construct for, one hundred percent,” observed Penny Arcade writer Jerry Holkins, “but it’s not actually that.”

Had Gigantic hit the market when Motiga wanted it to, the audience might have had time to adjust to its quirks. The initial response to the game’s unveiling in July 2014 was glowing; both Polygon and Kotaku called it “gorgeous,” and Kotaku exclaimed the following March that it “still looks pretty damn good.” Chung says the original plan was for the game to enter open beta by early 2015 and come out later that year, but that didn’t happen; that December, 16 Motigans were laid off, and the open beta was ultimately delayed until September 2016, for which McBee blames “so many roadblocks it’s hard to identify the biggest. The most consistent theme for us was that we were constantly against the ropes when it comes to funding.” At an independent studio, raising money can be challenging, especially given the scope and scale of a game like Gigantic, which had aspirations as an esport. “We were a smaller studio but not tiny, and it starts to get expensive when you have no revenue coming in,” McBee says. “So every few months it seemed like we were shopping the game around for more money.”

In 2015, Chung found a short-term fix for the funding problem that in retrospect stands out as his biggest regret among many. He made a deal with Microsoft that required Motiga to make the game exclusive to PC and Xbox One via a revamped version of the Windows Store that was then in development for Windows 10. The contract kept the studio’s doors open, but it also brought its work to a standstill, as the developers had to scrap the front-end user interface they’d put in place and start from scratch with something more console-friendly. “Large parts of the team had to put previously scheduled work on hold for nearly a year in order to meet our contractual obligations,” McBee says. “It felt like we were constantly behind where we needed to be, but at the same time we had no choice but to keep moving forward.” Because of the exclusivity agreement, Motiga also had to hold off on any betas or early-access programs that might have given the developers valuable feedback about their game.

You’re like, ‘Oh, awesome. Great. And you’re going to give us a lot of money to help us.’ But when you get there, they’re still building the apartment, and you’re expected to live in it.Vinod Rams, former Motiga senior concept artist

With the Windows Store a work in progress, Motiga had to feel its way forward over unsteady ground. Rams likens the episode to “a rich developer coming to you and saying, ‘We want you to live in the most state-of-the-art, cool apartment.’ And you’re like, ‘Oh, awesome. Great. And you’re going to give us a lot of money to help us.’ But when you get there, they’re still building the apartment, and you’re expected to live in it.”

The studio’s size swelled to a peak of a little more than 100 employees in August 2015, about 80 of whom were working directly on the game. Even so, the studio’s new obligations slowed the pace of Gigantic’s development so severely that despite having been bolstered by Microsoft’s cash, Motiga ran out of runway the following February. “February 9 was the darkest single day in my career,” Chung says. “That was the day when I had to let everyone in the company know they’d been let go.”

That day, Chung distributed reduction-in-force papers to every employee. The newly laid-off employees went back to their desks, but instead of packing their things, they kept working. The next day, almost everyone returned, so committed to the project that they were willing to work for free while Chung searched for a new funding source. “We did this day after day even though the future was 100 percent uncertain,” Chung says. Every morning, he would hold a meeting and update everyone on his ongoing attempts to secure funding, after which Phinney would go over development priorities. “Sometimes, a tech artist named Pat would bring out his ukulele and sing a rendition of an impromptu song about the situation,” Chung adds.

After putting the reduction in force into effect, Chung contacted recruiters and gave them the names of every Motiga employee affected. Many of them received offers from other companies, but all but a few who were feeling the financial strain hung on in the hope that Motiga and Gigantic could get back on track. “It was like, ‘Why would we go somewhere? There’s no way,’” Pikop says. “Like, if this might happen, we’re gonna see it through.”

The sight of the developers’ dedication helped convince Perfect World, a North American publisher primarily of free-to-play PC games and one of several would-be saviors that Chung was courting, to come to Motiga’s aid, providing enough capital to make up the missed pay and pave the road to release. “We only lost a handful of folks during the whole ordeal, which lasted for about a month,” Chung says. “I won’t be able to call it the happiest of times, but it was definitely the most rewarding time in my career.”

Motiga had been pulled back from the brink, but the delays had dug a hole for the studio that went beyond a temporary failure to make payroll, and the lost time was a handicap from which the company couldn’t recover. “In early 2015 we were the hot new thing, but by the time the game was available on the platform that we wanted to be on [Steam], the landscape had changed significantly,” Chung says.

It’s not that a Gigantic clone came along in the interim; even when Gigantic came out, its mix of MOBA elements, third-person shooting, and tactical, team-based gameplay still set it apart. Gigantic was a third-person, 5v5 game with Guardians; Overwatch is a first-person 6v6 game with no Guardians. But Gigantic and Overwatch—along with Hi-Rez Studios’ more recently released shooter Paladins—are hero- and team-based, brightly colored shooters with stylized looks (albeit more idealized and aspirational, in Overwatch’s case), and all of them are designed to be less intimidating than a full-fledged MOBA like League or Dota. “[Gigantic and Overwatch] really probably shouldn’t have been compared,” Pikop says. Nonetheless, he acknowledges that Overwatch was “an automatic point of comparison from everybody we talked to.” Motiga was in no position to wage or win a head-to-head fight for gamers’ mindshare with a behemoth developer/publisher that had a long-established brand. “Blizzard is a well-oiled machine, and we’re this small indie studio,” Rams says.

In retrospect, some Motiga alumni regret striving for perfection instead of releasing an unfinished-but-fun product that might have made it more quickly to a soon-to-be-saturated niche. “We were focused on quality and polish, when in hindsight just getting the game in the hands of as many people as soon as we possibly could would have put us in a much better spot to continue working on the game and starting to build a community while we got some revenue coming in,” McBee says. Motiga was worried about “burning” through potential players by releasing a substandard version of the game and failing to make a strong first impression, but by the time the superior product arrived, many of those players were effectively off-limits.

With little momentum in a marketplace that had largely forgotten about or given up on the game, Motiga’s pride in shipping its opus was counterbalanced by the knowledge that the long-delayed title faced an uphill climb. Chung says that about 2 million gamers played Gigantic on Xbox One/Windows 10, with roughly the same number playing it on Steam; McBee says the game peaked at about 15,000 to 20,000 contemporaneous players across all platforms, which would have been enough if Motiga could have kept them. But Chung reports that “the game did not retain the players at a rate that satisfied us and the publisher,” and he says he regrets not spending more money on user acquisition, which he says is vital for a free-to-play title that makes money through selling downloadable content like cosmetic upgrades and new character skins.

The battle-tested Motigans who made it to the Perfect World bailout could tell that the publisher’s leash wasn’t long. Rams recalls being in meetings in which a tantalizing future for Gigantic was discussed—“animation, web presence, web comics, all this stuff that all these companies do nowadays”—but none of those prospects materialized, which Rams and McBee say led to doubts about the enthusiasm that the publisher had expressed for the game. In May 2017, shortly before Gigantic came out, Phinney left Motiga; although most Motigans (and Phinney himself) are hesitant to talk about why, some suggest that his departure stemmed from problems with Perfect World. Between Phinney’s exit, earlier layoffs, and Gigantic’s shaky financial footing, the remaining Motigans weren’t taken by surprise when the last layoffs (which coincided with the closure of another Perfect World developer, Runic Games) came in November. “We were transparent with our numbers, and everyone at Motiga knew that the game wasn’t making money at the time,” McBee says, continuing, “So while no one was happy about it, I’d say most people understood why it was happening.”

After years of development, it’s difficult for a designer to experience a game as a first-time player would. And when a game doesn’t get the engagement that it needs to survive, its makers have to wonder whether they’ve lost their ability to evaluate their creation objectively. “Games find a way if they’re good enough, and maybe it’s the truth that Gigantic wasn’t good enough to be sticky,” Pikop says. But, he adds after further consideration, “I wouldn’t say that I think that.”

It would be one thing if Gigantic had produced a collective shrug among the people who played it. But while its audience wasn’t large enough to make its math work, it did have its diehards. Motiga interacted more closely with its community than most developers, running a program called “Core” that gave selected players early access to patches and new features in exchange for feedback that in turn improved the product. Browar, who became Gigantic’s community manager for Motiga and stayed on at Perfect World after the layoffs to go down with the (air)ship, first came to Motiga’s attention through his participation in that program. “The Gigantic community has some of the most dedicated and enthusiastic players I’ve ever had the pleasure of interacting with,” Browar says. “The community really rallied around the game and offered their own time to help educate new players, run tournaments, host events, and make memes.” McBee says Motiga saw some interest in Gigantic as an esport from fans and some event organizers but didn’t have the resources to help fan those flames.

Some members of the community, distraught that the game went away, have even banded together to develop a spiritual successor to Gigantic, which they’re calling Project: Stamina, a working title intended to remind them that game development is an endurance test. Project: Stamina’s producer, who goes by “Mr. Fancypants,” leads an all-volunteer team of 10 core developers, supported by 15 to 20 testers, all of whom are motivated by their desire to keep playing a Gigantic-esque game. “Denial is the first stage of grief, right?” Mr. Fancypants says. “Like, ‘No, Gigantic can’t end. If we can’t stop them from closing Gigantic, we’ll make a game that’s just as good as Gigantic.’”

Mr. Fancypants got into Gigantic last July and soon replaced Dota with Gigantic as his game of choice, partly because he found the community uncommonly friendly and inclusive; partly because Gigantic games typically lasted a manageable 15 to 20 minutes, compared to Dota’s 45 minutes to an hour; and partly because the game seemed so original. “You have all of these games that sort of use similar character silhouettes and similar color palettes and similar settings and similar gameplay goals, and then Gigantic was just doing none of that,” he says. “And I was like, ‘Wow.’”

The Project: Stamina team’s goal, Mr. Fancypants says, is to make “a game that anybody who has played Gigantic can pick up and say, ‘Oh, this is familiar.’” But the team also wants to put its own stamp on the genre rather than slavishly replicate Motiga’s. “We want to preserve the spirit of Gigantic; we don’t want to be derivative,” Mr. Fancypants says. The game is in the alpha stage, and Mr. Fancypants is mindful of holding future players’ hands by building in tutorials and standard game types in addition to modes inspired by Gigantic’s Guardian clashes. “We anticipate that more familiar game modes will help reduce the steep learning curve that new Gigantic players, myself included, struggled with,” he says.

The Motigans seem pleased by the community’s creative tribute. “I think Gigantic’s biggest legacy will be how we inspired other artists, designers, and studios to make their own cool thing,” Rams says. He, Pikop, and McBee all say that they’ve seen and heard evidence of the industry’s respect for the work the Motiga team did, which has made it easy for most former Motigans to find work on other games, each of which will owe some small debt to lessons learned during Gigantic’s gestation. “When I go to other studios and I see their inspiration board, there’s a lot of Gigantic art on there,” Pikop says, continuing, “There’s a clear impact that that [Motiga] team had on game art in general, I think. A lot of people really got to see something a little bit different. And so I think … that’ll stand the test of time.”

Whatever else they work on, the Motigans will carry with them the sense of satisfaction they derived from making Gigantic. “I’ve worked on cool stuff, but that was the game where I feel like that had a little bit of me, it had a little bit of everybody around me in it,” Pikop says. “Often that’s not the case when you make games.” Chung, who feels the same connection to what his company created, tried a few ways to save Gigantic before the shutdown, but now that it’s gone, he seems to have accepted its fate. “There is a sense of sadness but also of closure,” he says.

In the modern video game industry, where competition is cutthroat and some moneymakers that seem like institutions have very brief histories, making original games is so risky and expensive that publishers have gravitated toward “games as a service,” a model in which games are supposed to keep paying dividends long after their release dates, via subscription costs, downloadable content, or microtransactions. But when online-only games are gone, as Gigantic is, they leave even less of a trace than the single-player titles that people can pull off the shelves and replay at any point. Rams tries not to think that way. “The creativity will never go away,” he says. “You can’t delete that. Even if the game isn’t playable anymore, the art still lives.” And not just in art that the Motiga team has already created, but in the art it will create by virtue of the skills it honed while working on Gigantic. “When I look at my artwork pre-Motiga and now, it’s like this was a crash course in really good character design, collaboration, understanding how to communicate with art,” Rams says. “I wouldn’t be able to say that if I was just … making the next franchise game for whatever IP.”

Had fortune favored Gigantic, its story could have had a dramatically different denouement. “Could Gigantic have succeeded?” asks Michael Futter, the author of The GameDev Business Handbook. “Probably. It was a good game with a unique twist.” But circumstances are conspiring against many indie developers. “I’ve been around the video game industry long enough to know that making games isn’t easy, but my time at Motiga really reinforced just how difficult it is to make a great game that’s also commercially successful,” McBee says. More than 7,600 games were released on Steam last year alone (to say nothing of console exclusives and games on other software platforms), and the louder the din of competing titles, the more games get drowned out. For every hit like Cuphead that becomes a best seller, there are countless indie efforts that never come out or, like Gigantic, don’t turn a profit. “We only hear about the indie games that happen to find their footing,” Rams says.

Futter agrees with Rams’s assessment. “Even budget-conscious developers with great ideas and solid games are having a hard time right now,” he says, adding, “It’s not enough to make a great game anymore. You need the right PR message, the right people visibly playing your game, and you need to release at the right time.” Timing is particularly important in booming genres, any of which could be a bubble that’s about to pop due to a subsequent craze. “Even Overwatch is being surpassed by Fortnite as we speak,” Rams says. “So there’s always something coming over the hill.” The recent trend toward battle royale games may have helped snuff out Paragon, a MOBA made by the same developer responsible for the Fortnite phenomenon, Epic Games.

Going through the crucible of development made the Motigans close, and many of them have stayed in touch or even found ways to work together again in the months since the studio’s passing. On the evening of the 31st, hours after the last rounds of Gigantic were played and the servers shut down, about 30 Motiga veterans gathered at a Seattle brewery to reminisce. “Most people are happy at their new gigs, but a lot of us miss the rough-around-the-edges, scrappy way Motiga had to operate,” Rams says. Although some employers that have hired former Motigans have told them that they wanted to inject their own projects with a dose of “Gigantic style,” that originality isn’t always easy to foster in a new environment.

Gigantic’s wake incited some venting about Microsoft and Perfect World, and some melancholy, but most of the Motigans were in good spirits and feeling philosophical. “It was both one of the best experiences and one of the toughest experiences,” Pikop says of his time at Motiga. “Five years of craziness.” Having gone through that grinder, he’s emerged with a new understanding of what constitutes success. “Making games is less about what you make and more about who you make it with,” he says. “Whatever I do going forward, I will try my best to do the same thing: Try and make something unique, try and make something that people will remember, and try and work with people that want to do the same. … It’s so much more fun to say, ‘Let’s make something special and something new.’ Not easy, but fun.”