Good Game Well Played: The Story of the Staying Power of ‘StarCraft’

Twenty years after Blizzard’s baby redefined a genre and spawned the esports movement, it remains a timeless proof of concept for what online competition can be

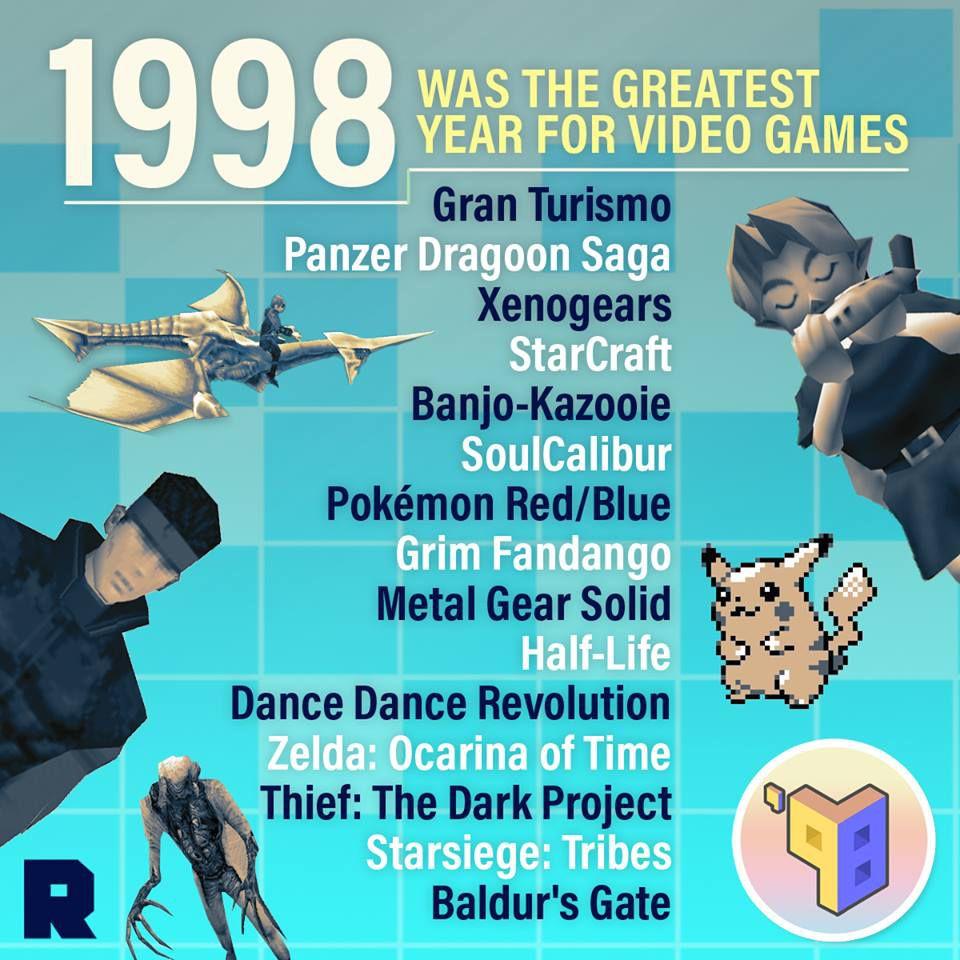

Art may largely be a matter of taste, but one conclusion is close to inarguable: 1998 was the best year ever for video games, producing an unparalleled lineup of revolutionary releases that left indelible legacies and spawned series and subcultures that persist today. Throughout the year, The Ringer’s gaming enthusiasts will be paying tribute to the legendary titles turning 20 in 2018 by replaying them for the umpteenth time or playing them for the first time, talking to the people who made them, and analyzing both what made them great and how they made later games greater. Our series continues today with StarCraft, the seminal real-time strategy game by Blizzard Entertainment that reinvented the RTS genre, set the stage for global esports, and established a franchise that remains central to today’s competitive-gaming scene.

On Saturday, StarCraft will turn 20, and we’ll marvel at the mileage on an almost ageless game. Three days later, professional StarCraft competitors will take the stage in a standing-room-only studio in South Korea, selecting their species and pitting Protoss against Terran and Terran against Zerg—not because it’s the game’s 20th anniversary, but because it’s Tuesday. They played the previous Tuesday, too, with thousands of fans streaming on AfreecaTV, the Korean video-streaming service that sponsors the Afreeca StarCraft League.

The aesthetics of a live-streamed StarCraft match in 2018—packed seats, bright blue lighting, walls festooned with branded banners, enthusiastic commentators, and, of course, cameras trained on headset-adorned dealers of digital death—are recognizable to spectators of any esport. But the existence of a shared visual language of esports stems from StarCraft as much as any other game——as, for that matter, does the existence of esports at all. And StarCraft, somehow, is still being played, at a time when some of its contemporaries are all but unobtainable.

Two decades after the day when StarCraft players first flooded onto Blizzard’s online gaming platform, Battle.net, in force, the game remains one of the finest examples of the real-time-strategy style that made the bones of Blizzard, its renowned developer. It launched a fictional universe, spawned a successful sequel, and inspired Blizzard to take on even more ambitious follow-up projects. Even more importantly, it provided a genre-redefining proof of concept for what online competition could be, fueling the growth of an industry and subculture that have entered the mainstream today. “Back in the day, folks in the U.S. and Europe looked to South Korea’s Starcraft scene for inspiration,” says T.L. Taylor, a comparative media studies professor at MIT who has written a number of ethnographic books about online gaming. “It provided a playing field for incredibly talented players to show us what true virtuosity in digital gaming could look like. StarCraft was also a title a lot of folks currently working in the industry cut their teeth on. Its importance can’t be overstated.”

Neither can the difficulty of the crunch time that created it.

Orcs in Space

On one bleary day among many during the development of StarCraft, Blizzard VP of research and development Patrick Wyatt, who ranked third in the company’s hierarchy, walked into the office of StarCraft lead designer James Phinney. “I came to ask him for some design clarification on something, and he’s like, ‘Hang on a second,’” Wyatt says. “He leans over, and he vomits in a trash can because he’s been working so hard. And then he’s like, ‘OK, what was your question?’ So yeah, it was pretty physically taxing.”

StarCraft may be one of gaming’s best examples of “order out of chaos.” It’s fairly rare for any reminiscing designer to say that a seminal project went off without a hitch; in game development, delays and midstream reconceptions are standard—occupational hazards of the inexact art of creating collections of code that feel fun. Even so, most development cycles pale in comparison to the torturous process that yielded StarCraft, which Wyatt remembers as “the hardest, most grueling period” of his career. “The lessons that I learned from StarCraft were a whole bunch of anti-patterns,” says Wyatt, who’s now the senior principal engineer at Amazon Game Studios. “Like, ‘I will never do it again this way.’ We just made so many mistakes. I mean, it was a labor of love, but it was also a Sisyphean task, and we shot ourselves in the foot so many times.”

We just made so many mistakes. I mean, it was a labor of love, but it was also a Sisyphean task, and we shot ourselves in the foot so many times.Patrick Wyatt, Blizzard VP of research and development

When work on StarCraft began in 1995, Blizzard appeared well-positioned to produce another hit. The company, which was founded in 1991, had released Warcraft: Orcs & Humans in 1994 and was preparing to ship its sequel, Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness, in December ’95. Both games were innovative, critically acclaimed, and financially successful examples of the ascendant real-time-strategy genre in which players harvest resources, develop technology and infrastructure, and build mobile units to attack an opponent on a large, partially obscured map with all of the action playing out uninterrupted rather than in a turn-based, stop-and-start format.

The world of Warcraft (hey, sounds like a good name for a game) was medieval-looking and fantasy-themed, and after churning out two titles in that series, the company’s creatives were ready for a change. “The artists at Blizzard at the time were expressing a desire to work on something other than fantasy, because they had been drawing Warcraft characters for a few years and they kind of wanted to do something new,” says Mike Morhaime, Blizzard’s cofounder, president, and CEO. “It was pretty natural for us to think about something set in the science-fiction universe.” A new game in the same vein as Warcraft, but more sci-fi flavored: Perhaps it could be set in space … which has stars … StarCraft! Boom.

Although StarCraft would make its biggest mark as a multiplayer game, its single-player campaign also pushed past the previous standard for RTS titles. Its computer-generated cutscenes tested the limits of 1998 system specs, and strategically placed pieces of audiovisual flair—portraits decorating the ready rooms as the player prepared to launch missions, voiced dialogue in the midst of the action—deepened the user’s sense of immersion. Those subtle touches “built a much stronger relationship with the characters that were in this game than we were able to pull off in Warcraft II,” says Blizzard production director Chris Sigaty, who served as the quality-assurance lead on StarCraft and later went on to produce its long-awaited 2010 sequel, StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty. In making StarCraft, Blizzard learned that a little in-game lore goes a long way, a lesson that has since served it well even in online-only games such as Overwatch, whose heroes have histories that make the multiplayer slaughter seem less mindless and unmotivated.

StarCraft’s smart storytelling, paired with its rich premise and setting—a 25th-century fight for hegemony between the exiled-from-Earth Terrans; the insectoid, gene-splicing Zerg; and the psionic, high-tech Protoss, all playing out in the distant Koprulu Sector of the Milky Way galaxy—represented one major way in which the game improved upon Blizzard’s earlier efforts. The second way would set it apart not just from Warcraft, but from any RTS game that had gone before.

Although Warcraft included multiple species—humans and orcs, as the subtitle said—the differences between them were mostly cosmetic, with at most minor departures in stats and abilities. They offered some variety in appearance, but very little from a strategic standpoint. “We had thought that the only way to balance [the gameplay] was to keep it as closely mirrored as possible,” Morhaime says.

We could just tell we had something big on our hands.Wyatt

The emergence of Magic: The Gathering, a popular collectible card game that debuted in 1993, gave Blizzard the confidence to take one giant leap for RTS-kind. Magic cards came in five different colors, each of which featured specific strengths and weaknesses. Those attributes meshed in an intricately designed system of checks and balances that prevented any one class from becoming too powerful. In designing StarCraft, Blizzard borrowed that idea. “For every ability and every unit power that there would be, there would have to be a counter,” Morhaime says. “So if you knew what your opponent was coming at you with, there would be a ... strategy that would be able to counter it, and we thought we’d be able to balance the game that way,” Morhaime says.

That concept formed the basis of the tactical depth that’s sustained StarCraft long after most multiplayer games fall out of favor. It also contributed to long delays. Initially, the company planned to make StarCraft in one year, but the game’s revolutionary nature, coupled with the demands of Diablo, a hack-and-slash action RPG that Blizzard was developing simultaneously (and would eventually release on the last day of 1996), made that target unrealistic. The company then set its sights on 1997, but that too proved untenable; although Morhaime says he “desperately” wanted to avoid additional delays, the work continued into 1998. “It was incredibly difficult,” Morhaime says. “This really consumed the company. The team really crunched for about eight months on the game.”

“Crunch” is the industry term for the round-the-clock, all-hands-on-deck mad dash for the finish line that sometimes precedes the release of a game—often with harmful effects, as Phinney found out. “There were multiple nights where I slept on the ground in the office and woke back up and got at my desk, so 80-plus hour weeks were very common,” Sigaty says. A combination of youthful energy, professional fervor and, possibly, Stockholm syndrome kept the team’s morale from fading. “I didn’t think of it as a bad quality of life, honestly,” Sigaty says. “It was just being dedicated to what we were trying to get done.” Wyatt remembers that the team maintained slightly irrational expectations of its own productivity throughout the extended development, which acted as a bulwark against disappointment as each provisional deadline blew by. “The bulk of it was just optimism that we could get it done, and that we were just a few weeks away,” Wyatt says, laughing. “Or, you know, maybe several months away, sort of forever.”

The problem wasn’t just the need to craft a compelling campaign populated by fully fleshed-out characters and species—a process overseen by Phinney (when he was keeping his food down) and his colleague Chris Metzen—coupled with the complexity of the tripartite playability, which Sigaty says sometimes “almost felt like an unsolvable problem.” It was also that in one way, the team hadn’t been ambitious enough. The first StarCraft design that the public saw, Sigaty says, was “a quickly turned-around version that we put out there, built on top of Warcraft II.” Blizzard brought that alpha version of the game to the industry’s annual hypefest, E3, in May 1996, where it underwhelmed gamers who were expecting to see something more than a reskinning of the same old design. “It was pretty panned,” Sigaty says. Wyatt sums up the public’s derisive review: “purple orcs in space.”

After returning from E3, the team reluctantly concluded that StarCraft required a reboot. “It was pretty grim,” Wyatt says. “We just couldn’t conceive that we could continue development as it was going. There was just no chance that we were going to capture people’s interest.”

One of the nails in the StarCraft alpha’s coffin was a competing RTS that had stolen the spotlight at E3, Ion Storm’s Dominion: Storm Over Gift 3. The footage Dominion debuted at the trade show teased clever mechanics that the Blizzard team hadn’t dreamed of, as well as an isometric perspective that produced a 3-D effect, making the top-down, 2-D look of Warcraft and Blizzard’s first pass at StarCraft seem stale. “It was just so ridiculously better than our game in the way that it looked, we just were depressed,” Wyatt says. “And so when we got back, it’s like, ‘OK, we’re changing the game. We’re changing everything about the game.’”

Later, Wyatt says, Blizzard hired one of Ion Storm’s cinematics artists, who told the team that the Dominion footage shown at E3 hadn’t been playable, as the company had claimed; it was just a pre-rendered video created specifically for E3. Both Blizzard and the public had fallen for the ruse. When the game was finally released, a few months after StarCraft, Computer Gaming World named Dominion the runner-up for its “Coaster of the Year” award, writing, “Ion Storm’s initial release sailed like a lead balloon, complete with overhyped and ineffectual AI, 1995-era graphics, and a backstory so bad that it had us wondering why we even briefly stopped playing StarCraft for this.” Dominion’s main contribution to the annals of gaming, it turned out, was indirectly inciting a facelift for StarCraft. “They tricked us into making the game that they were going to make,” Wyatt says.

Sigaty remembers Blizzard’s response to that setback at E3, which defined a new direction for StarCraft, as a pivotal moment for the company as a whole, one that would shape its design philosophy in future sequels to its existing franchises as well as in future successful spin-offs and originals such as World of Warcraft, Hearthstone, and Overwatch. “We could’ve reacted offended, shut it down, decided not to go forward because the reaction was poor, but instead we reacted exactly the opposite and the engine was rewritten in a very short period of time,” Sigaty says. “The reaction was to level up … how [grandly] we thought of this game now. It was gonna be even more grand. And that reaction became this commit-to-quality ideal that we have today.” In a matter of months, StarCraft went isometric also.

The new perspective erected obstacles of its own; suddenly, AI units that had been designed to move on a 2-D plane had to be taught how to navigate a different type of topography. “The path-finding was so wretched,” says Wyatt, who describes his role as a “rescue programmer” who roved from one aspect of the game to another, ferreting out and fixing issues along the way. “You had to really baby your units in order to get them across the map and attack and things like that. Bugs galore. … Lots of units just wouldn’t work properly.”

Some particularly bad bugs caused crashes or desynchronization between the game-states on each player’s screen, rendering StarCraft unplayable. “We were just really beating our heads against it,” Sigaty says. In a way, though, the existence of those show-stopping bugs worked in the game’s favor; because the game couldn’t ship until they were addressed, anyone who wasn’t working on eradicating them had more time to tighten and polish other areas.

Blizzard’s disorganized testing process, Sigaty says, was a “black box” in which new builds lacked documentation explaining what had changed since the previous one, forcing the QA team to guess which elements were bugs and which were there by design. “We really didn’t get it locked down until really, really late,” Morhaime says. Yet bug fix by bug fix, the team turned the tide and crunched toward completion, throwing programmers at each problem in a Zerg Rush of overtime hours. Like a lot of games in development, StarCraft seemed troubled until suddenly, one day, it didn’t. “It was probably only a few months before we launched that the game really came into its own, and it’s like, ‘OK, now everything is starting to work,’” Wyatt says. Any fear the team felt during its months stuck in stoppage time melted away. “We knew by the end that we had something we were all very proud of,” Sigaty says. All that remained was for StarCraft to correct the public’s poor first impression.

Going to Battle(.net)

Morhaime says his first inkling that StarCraft was going to be big—really big—came on April 1, 1998, the day after StarCraft came out. When he went into work, he found the office full of people playing the game, including the programmers and QA testers who’d just spent sleepless months finishing it. In theory, they should have been sick of StarCraft. But there they were. “For them to come into the office on their own time just to play the game, I thought that was the best sign that you could possibly see about a game,” Morhaime says.

The next positive sign: Tons of other people were playing it, too, with legions logging onto Battle.net, which had launched alongside Diablo. “Because we had Battle.net, we could watch as people got online, and … the concurrency just shot up and people started playing lots of games,” Wyatt says. “And we could just tell we had something big on our hands.”

As vast masses of players began taking the game for test drives under less controlled conditions than the ones in which the team had prodded it prerelease, the team shifted its focus to putting out patches to squash bugs or counter problems with balance. The availability of Battle.net data and players’ increasing tendency to report problems on forums made it easier to identify areas of need than had been the case with Warcraft a few years before, although the number of people playing subjected the servers to greater strain. “The popularity of StarCraft did surprise us, and we definitely had to invest in our Battle.net infrastructure and in being able to support a growing number of concurrent players,” Morhaime says.

As is always the case with online games that millions of people play, the top-tier players’ skill soon surpassed that of the designers. Sigaty remembers the unnerving experiencing of seeing StarCraft players get so good that they played in ways his QA crew had never anticipated. “Watching their use of hotkeys and just how many actions per minute they were going through, I would get totally petrified that, ‘Oh my god, we never tested a game like this at all. This thing’s gonna crash or they’re gonna turn up a bug that we didn’t find,’” he says. The game proved surprisingly resilient, and Blizzard kept the balance tweaks and content coming, releasing acclaimed expansion pack Brood War just eight months after StarCraft’s arrival.

It was right around then that StarCraft began to graduate from a hit stateside to a global phenomenon. “By the time we were making Brood War, we were starting to see some really crazy things come back,” Sigaty says. “It was a [domestic] commercial success, which was awesome, but the success in Korea was where things really started to shock us.”

‘What the heck?’ Our VP of this little company is meeting with the vice president of a country.Chris Sigaty, Blizzard production director

Blizzard hadn’t anticipated that StarCraft would catch on in South Korea; they hadn’t localized it, so Koreans could only play it in English, and Wyatt says that the company hadn’t expected to sell more than a few thousand copies in the country. Sigaty remembers that shortly before or after the release of Brood War, Blizzard vice president Paul Sams flew to Jeju Island and met with South Korea’s vice president. “[It] was like, ‘What the heck?’ Our VP of this little company is meeting with the vice president of a country,” he says. Sams brought back a binder filled with photos of a stage show that his hosts had put on, in which cosplaying performers had dressed up as StarCraft creatures like zealots and hydralisks with detachable talons. “I was looking at this going, ‘Oh my gosh, what is going on?’”

Morhaime, who says that “Korea really wasn’t on our radar at all before StarCraft,” made a trip to South Korea himself years later, when the game had sold its two millionth copy (in a country of fewer than 50 million people). He attended an esports-style event at a large auditorium, with a vocal capacity crowd and throngs of people who couldn’t get in milling around outside. “I had never seen anything like that,” he says.

The explosion of StarCraft in South Korea stemmed from a confluence of sociocultural factors, none of which was Blizzard’s doing but all of which were to Blizzard’s benefit. In his 2010 book, Korea’s Online Gaming Empire, Dal Yong Jin, a professor in the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University, explains that in 1995, the South Korean government enacted efforts to install high-speed internet on a massive scale, a movement that accelerated when a 1997 financial crisis led to large-scale unemployment and forced the South Korean economy to shift from heavy and chemical industries to “a more IT-oriented structure based on telecommunications and computers.” Some of the workers who had been laid off started PC bangs, 24-hour internet-café-like establishments that weren’t expensive to operate. In 1997, there were only 100 PC bangs in South Korea; by the next year, there were 3,000, and that total had increased nearly eightfold by 2001.

Many Koreans’ first exposure to broadband came in PC bangs, where young and out-of-work locals would gather to socialize, trade stocks, and play games online. The combination of cheap, high-speed internet access, friends, and free time made each PC bang a potential focus of infection for StarCraft. The game’s original Korean distributor, LG Electronics subsidiary LG Soft, was hit hard by the recession and downsized severely, which created an opening for a former LG Soft executive named Young-man Kim to form his own company, HanbitSoft, and take control of the license. Wisely, the first thing that Hanbitsoft did was distribute free copies of StarCraft at the multiplying PC bangs, which soon made it many players’ go-to game. “When you got into an argument with a kid at school, instead of ‘Hey, meet me after school in the playground and we’ll settle this,’ it [was] like, ‘Meet me in the game room and we’re going to settle this over a game of StarCraft,’” Morhaime says.

StarCraft sold 120,000 copies in South Korea in 1998, more than one million in 1999, and 2.5 million over the next four years, as a virtuous circle took hold: The spread of broadband propelled StarCraft sales, and StarCraft sales propelled the spread of broadband. Before long, South Korea had developed an affinity for online gaming that no other country or culture could rival, and leading StarCraft players, Jin tells me, were greeted with “the kind of fan frenzy that anywhere else would be reserved for rock stars or movie legends.” The aftereffects of South Korea’s StarCraft-fueled status as an early adopter of esports are still apparent today; earlier this year, South Korean natives composed roughly 40 percent of players on opening-day rosters in the Overwatch League’s inaugural season. Blizzard’s first “really big breakout global title,” as Morhaime describes it, paved the way for those that have followed.

Blizzard didn’t create the conditions for StarCraft to catch on; as Wyatt says, “it wasn’t by planning, it was by happenstance.” Blizzard did, however, create a highly communicable game: There’s a reason why it wasn’t Dominion that repeated the rewards of fantastic timing. In addition to designing a deep and satisfying strategy game with decades’ worth of replay value, Blizzard also streamlined the process of online play. Prior to StarCraft, online matchmaking was a painful process. In Warcraft II, Wyatt says, “You’d create a game, and then you would join, and you’d all sort of argue over what the parameters of the game should be, which led to a lot of people dropping out … and then you’d have to go and get more players together again.” In StarCraft, the creator would simply pick preset parameters, and players could join if those parameters appealed to them.

More important, Battle.net’s price couldn’t be beaten: It was free. Once a player purchased StarCraft, he or she could keep playing online indefinitely without any additional charges. Before Blizzard launched Battle.net, online gaming services such as Total Entertainment Network (TEN) had begun to charge subscription fees, but StarCraft undercut them, much to their dismay. TEN ceased operations in October 1999. “Starcraft revolutionized the way that people thought about online game networks, and it basically crushed the possibility to charge hourly fees for games,” Wyatt says, adding, “In some ways, I think that eventually led to the whole free-to-play genre.” Because Battle.net had no barrier to entry, Starcraft drew a giant pool of players, making finding games easy—which, in turn, made the prospect of playing even more appealing. The virtuous circle had struck again.

Last year, Blizzard made StarCraft and Brood War downloadable for free. Months later, both games got remastered, giving them even longer leases on life. Their indirect influence is incalculable, and their list of direct descendants will grow. Sigaty, who says the pressure of succeeding StarCraft was “always looming” in his mind as he produced its sequel, won’t commit to making StarCraft III, but he will confirm that the franchise has a future beyond Remastered matches—which are still sometimes fixed, a testament to the stakes attached to their outcomes even in 2018. “We definitely will revisit this world again,” he says, adding that he sees StarCraft as critical to the “core of Blizzard’s DNA.”

StarCraft’s breakout was both a fluke and the product of a painstaking plan. “Even though we knew we had a good player-vs.-player game on our hands, the level and the stature it got to was beyond all our wildest expectations,” Sigaty says. It was the work of an experienced real-time-strategy designer staying within its wheelhouse—“we had a lot of bites at the apple, and we learned how to do it,” says Wyatt, who created RTS staples like the “click and drag”—and the experimental result of trying things for the first time. And although the game was intended to exceed the typical title’s shelf life, it went well beyond what Blizzard believed the limit to be. “I don’t think any of us really appreciated … how impossible it would be for anybody to master it,” Morhaime says.

Blizzard’s cofounder claims, uncontroversially, that StarCraft “laid the foundation for modern esports,” adding that the game’s success in South Korea made him dream of a world like the one we’re approaching, where online competition could permeate pop culture at large. But before StarCraft, Morhaime says, “[that] really wasn’t something that we thought about at all.” Maybe that’s the hallmark of the most monumental games: They make us eager for a future that we formerly couldn’t conceive.