Last Tuesday night, Astros starter Justin Verlander stupefied the Yankees. Verlander’s outing—eight innings, 14 strikeouts, no walks, three hits—was definitely the best of his short tenure with the Astros, and one of the best of his long and probably Hall of Fame–bound career. It was Verlander’s third-ever 14-strikeout game, but the first in which he hadn’t walked a batter. All in all, it marked his seventh career start with a game score of 90 or better.

That same night, Yankees starter Jordan Montgomery got hurt after just one inning, but the New York bullpen kept pace with Verlander, as they delivered the game to the ninth inning the way they’d found it: scoreless. It was only against Ken Giles, the Astros’ nastiest and sometimes best reliever, that New York was able to get a rally going. A single by Aaron Judge, a double by Didi Gregorius, and a strikeout by Giancarlo Stanton brought Gary Sánchez to the plate.

In Minute Maid Park, right-handed hitters like Sánchez can practically reach out and touch the Crawford Boxes, which make Houston’s ballpark look like more of a hitter’s park than it is. The out-of-town scoreboard on the left-field wall is like the continental shelf; once you get past it, it gets real deep, real fast. The marker on the center-field wall where Tal’s Hill used to be says “409,” but it might as well read “4,009.” In order to hit a pitch out to dead center, you have to annihilate the baseball.

Sánchez saw one pitch from Giles, an 88 mph slider that didn’t slide all that much. He annihilated the baseball.

One batter later, Giles walked off the mound in a cartoonish fit of rage that would’ve been hilarious if it weren’t also a little concerning. The Yankees won 4-0, thanks mostly to Sánchez’s bat.

Seven months prior, Verlander had thrown another gem against the Yankees in Minute Maid Park: 13 strikeouts, one walk, five hits, and a single earned run in Game 2 of the ALCS. That time, he went nine innings and threw 124 pitches. Once again, Sánchez figured in the ending.

With José Altuve on first base, representing the winning run, Carlos Correa doubled off Aroldis Chapman to right center. Altuve’s one of the fastest runners on the team, and Astros third base coach Gary Pettis wakes up every morning windmilling imaginary runners home, so naturally he sent Altuve.

Judge made a great play to cut off the ball, and Gregorius’s relay throw home was a little short but still on line. Between the moment the ball reached Sánchez and the moment Altuve touched the plate, you could have said “Oh shit, he’s out” out loud with time to spare. But Sánchez couldn’t handle the short hop cleanly, and while Altuve was skimming across the plate, Sánchez was feeling around for the ball like he was looking for his glasses on a nightstand.

“Gary Sanchez blows game” read the headline on NJ.com, and the first four paragraphs of Randy Miller’s gamer confirm it: “Altuve started the winning rally with a one out single to left, Correa followed with a line double to right that won the game … thanks to Sanchez’ mistake.”

There’s no guarantee that the Yankees would have won that game if Sánchez had made that play, but if they had, they would’ve gone back to New York with the series tied. And considering how comprehensively the Yankees routed Houston in those three games, they likely would’ve won the series and the pennant.

Therein lies the duality of Gary Sánchez, who among players with 500 or more PA since 2016 is 14th out of 321 in wRC+ and seventh in isolated power. But he also exists in the public imagination as a catcher who sometimes has trouble catching. He can change the game with his bat, but the worry is that he can also change it with his glove.

The road from the Dominican Republic to the big leagues is a long one, even after a player signs with a club. A 21-year-old college draftee can make the majors in a year, but a 16-year-old Dominican prospect faces a much more complicated journey. Turning any 16-year-old into a professional is a massive developmental project, and the younger the player, the more physical development he has in front of him. In addition to cultivating their own game, Latin American players typically have to learn a new language, adjust to a new culture, and live apart from families they might end up seeing only rarely once they make the Show.

Every additional hurdle makes it significantly harder for a given prospect to make the majors, or for scouts, analysts, and fans to project what kind of player he might become. For that reason, the annual feeding frenzy over Latin American teenagers produces a list of names that gets filed away for years and mostly forgotten by fans. These players usually don’t make any top-prospect lists right away—even the ones who command seven-figure bonuses.

Sánchez is one of the few exceptions. His $3 million signing bonus was, at the time he signed with the Yankees, the second-richest ever given to a Dominican 16-year-old. He was one of two jewels of a class that also included Miguel Sanó, who beat Sánchez’s bonus three months later. Sanó was the subject of a documentary film, Pelotero, that included details of his failed courtship by the Pittsburgh Pirates, whose international scouting director tried to leverage rumors that Sanó was older than he claimed to be into a lower signing bonus. Sánchez caught some of the reflected attention from that film, but he also had a special skill set.

Kevin Goldstein, then of Baseball Prospectus, put it succinctly in his top-11 prospects list for the 2011 Yankees: “While he’s still a long ways away, Sanchez at least has the potential to be the rare catcher who hits in the middle of a lineup.”

Goldstein’s initial read on Sánchez was spot on, even from several years out: from “the ball just makes a different sound coming off his bat, and scouts have little problem projecting him to hit for both average and power throughout his development,” to the assertion that while he has a plus arm, “His defense still needs considerable work, in particular his receiving skills.”

I’ve said it many times before: I’m not perfect and I’m not going to be perfect.New York Yankees catcher Gary Sánchez

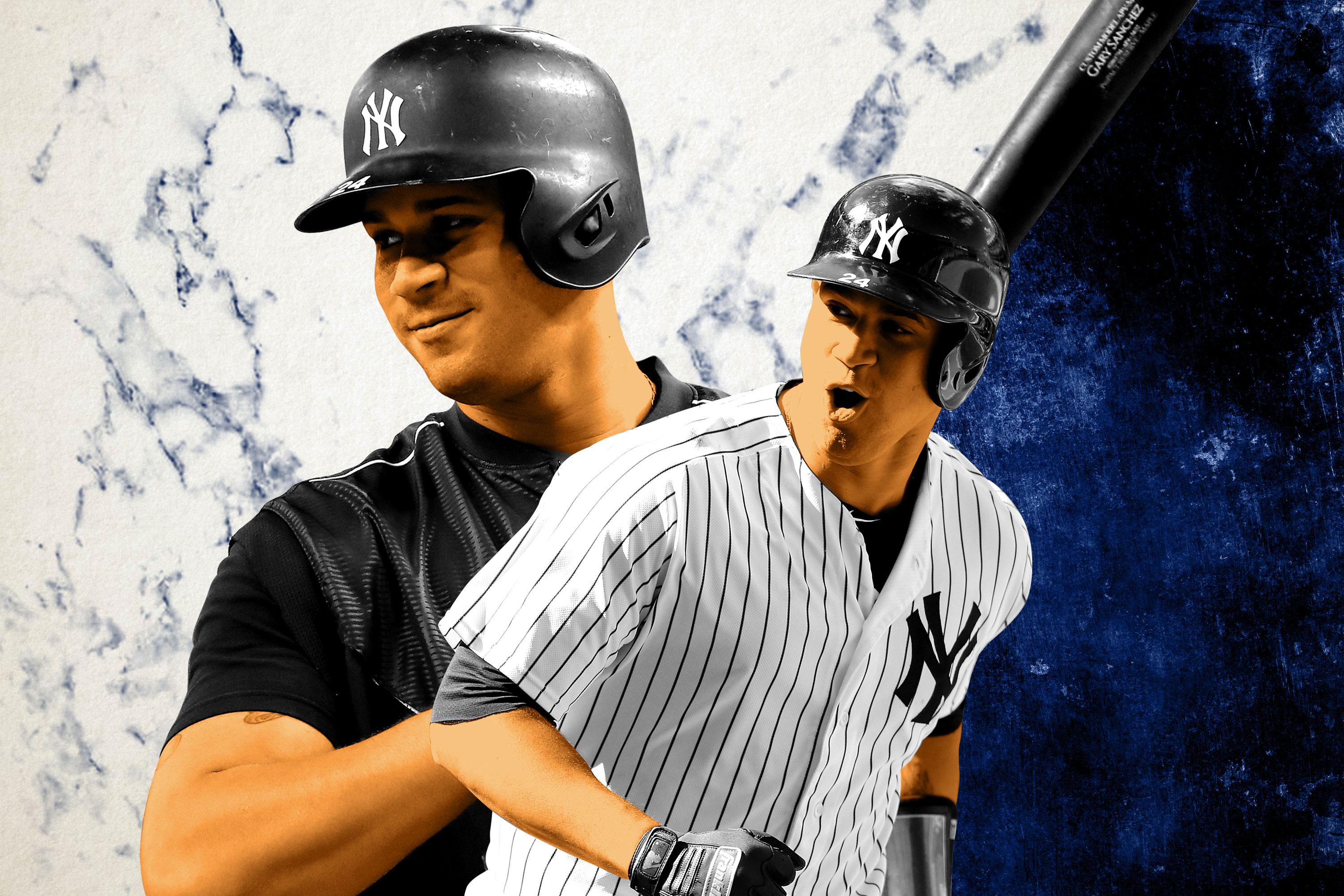

Sánchez, who’d just turned 18 when he made his first BP Top 101 in 2011, was just 195 pounds. But since then, he’s matured into a frankly gigantic 25-year-old, with wide shoulders and hips that would set him apart in any clubhouse that didn’t also include Judge, Stanton, Dellin Betances, and CC Sabathia. Sánchez is the kind of person who makes the earth wince when he walks, and that strength translates into outrageous power. The line about the ball sounding different off Sánchez’s bat is a cliché, but it’s true. With Sánchez, it’s less of a crack than a boom.

Tempting as it is to dismiss the flaws in Sánchez’s game as nit-picking by a hysterical New York media and a spoiled Yankees fan base, he is bad at blocking pitches, and he knows it.

“I’ve said it many times before: I’m not perfect and I’m not going to be perfect,” Sánchez told me through an interpreter. “Mistakes are going to happen, but at the end of the day, you have to do the best you can to help your team.”

In 2017, Sánchez tied for the league lead in passed balls, with 16. And with him behind the plate, Yankees pitchers threw 53 wild pitches, second-most of any catcher in baseball. This year he’s once again tied for the league lead in passed balls (six) and second in wild pitches (20). It’s too early in the season to draw conclusions from Baseball Prospectus’s more sophisticated blocking runs stat in 2018, but last season, Sánchez was 71st in blocking runs out of 73 catchers with at least 1,000 chances.

In one anecdote that’s so extreme it’s hilarious, Sonny Gray has thrown 26 2/3 innings with Austin Romine behind the plate, compared with just 6 1/3 over two starts with Sánchez. With Romine behind the plate, Gray hasn’t thrown a single wild pitch, but with Sánchez behind the plate he’s thrown five. A New York Daily News article on Gray’s productive partnership with Romine includes polite assurances from the two, and manager Aaron Boone, that everything’s fine between Gray and Sánchez.

Whatever the catcher’s teammates and coaches are saying, this feels like a big deal. Last season, Sánchez allowed 69 combined passed balls and wild pitches, while the likes of Buster Posey, Austin Hedges, and Yadier Molina—baseball’s best all-around defensive catchers—were all in the mid-30s. Plus, the one misplayed short hop in the playoffs had a huge impact on the Yankees’ season. But in aggregate, how big a hole is Sánchez’s blocking putting the Yankees in? According to BP, last year it was 2.6 runs, a little more than a quarter of a win.

So let’s go back to the other half of the Sánchez equation—what is the value of a catcher with a middle-of-the-order bat?

Catcher is so different from other defensive positions, and so much more demanding, that measuring offensive output at that position has always been a little tricky. It’s so demanding that outstanding defensive catchers can become All-Star–level players without much offensive output at all.

“Catching is a physical position, but at the same time I’m used to it,” Sánchez said. “To me, the biggest challenge is being consistent on both sides of the ball. That’s hard to do, and that’s what I want to do all the time. If I’m able to be consistent defensively and offensively, that’s when I feel my best. But that’s not easy.”

Sánchez has a tricky body type for catching. While Posey and Hedges have lithe hockey-goalie bodies, Sánchez has a wider base, like an offensive tackle in miniature. Lugging that body around can be exhausting while wearing the tools of ignorance and squatting 150 times a night in the summer heat. On the opposite end of the positional spectrum, some players find it hard to lock in as a DH because they’re just sitting around between at-bats rather than playing the field. Sánchez doesn’t experience either effect, or he experiences them both equally, because his career splits by position are almost identical: .273/.345/.558 as a catcher, .266/.339/.552 as a DH. Consistent, in other words.

But the defensive spectrum adjustment from catcher to DH is 30 runs—three wins, in other words, so Sánchez is much more valuable to the Yankees behind the plate. (Three wins above replacement is an entire 2017 Joey Gallo, give or take.) And as a catcher, Sánchez is one of the best hitters in the game. Since 2016, Sánchez’s rookie year, 36 players have recorded 500 or more big league PA, while playing at least 70 percent of their games at catcher. Buster Posey is second in OPS+, at 122, and the mid-120s is a reasonable offensive ceiling for a catcher. Johnny Bench, Yogi Berra, and Roy Campanella are three of the best catchers of the 20th century, all Hall of Famers, with eight MVP awards among them. Bench’s career OPS+ is 126, Berra’s is 125, and Campanella’s is 123.

Sánchez’s career OPS+ is 132. He’s one of three catchers with 500 or more career PA and a career OPS+ of 130 or better. The all-time leader, Mike Piazza, is in the Hall of Fame, and Posey, who’s in second place, will join Piazza in Cooperstown five years after he retires.

In 2016, Sánchez hit 20 home runs in just 53 games, building a credible Rookie of the Year case (he finished second to Detroit’s Michael Fulmer) on a third of a season’s work. Sánchez’s 2016 season was only the second time a catcher had posted an ISO of .350 or higher in a season of 200 plate appearances or more. Sánchez hit his 60th career home run in his 201st career game—the only player to get to 60 in fewer games is Judge, who’s superseded Sánchez as the Yankees’ big-ticket slugger.

Or rather, Judge is one of the players who’s superseded Sánchez. After the Stanton trade and breakouts for Judge in 2017 and Gregorius in 2018, Sánchez might be as far down as fourth on the Yankees slugger pecking order.

“We all have a role here,” Sánchez said. “For me, it’s about doing my job. It doesn’t matter what kind of attention I’m getting.”

Sánchez doesn’t have to be the guy—he doesn’t even have to be the player he was as a rookie. There are 14 players in the Hall of Fame who played at least half their games at catcher. The median career OPS+ among that group is 126, and the median Hall of Fame catcher is worth about 4.8 bWAR per 650 plate appearances. Through the equivalent of a little less than two full seasons, Sánchez is averaging 5.4 bWAR per 650 plate appearances. Sánchez doesn’t have to improve at all to be a Hall of Fame catcher; he just needs to be exactly what he is now for another five or six seasons, then experience a normal decline in his 30s. Even for a player as hyped as Sánchez, and even on a team where expectations are as high as they are on the Yankees, the Hall of Fame was never the standard, but that’s the track Sánchez is on.

Sánchez was among the worst blockers in baseball last year, but that plus throwing arm was rated ninth out of 73 catchers with 1,000 chances or more, almost exactly erasing the deficit caused by his blocking. And his receiving skills have improved, to the point where he was 4.6 framing runs above average in 2017, 21st out of 73 catchers with 1,000 chances or more. All told, Sánchez was an average-to-slightly above-average defensive catcher in 2017, not the butcher he’s purported to be.

It’s not that the criticism of Sánchez’s blocking is invalid, or that it doesn’t cost the Yankees big when he screws up in big moments. It’s that Sánchez’s blocking isn’t as important as it’s made out to be; the criticism might be so loud only because it’s the only weakness in his game. Sánchez might lose the Yankees an occasional game with his glove, but for every time that happens, he’ll win many more with his bat.