Last Tuesday, Astros right fielder Josh Reddick returned from a brief stay on the seven-day disabled list and immediately made clear that the time he’d missed with a mild concussion hadn’t impaired or altered his game. In his first start back, he singled and doubled with the bases empty, then struck out swinging with runners on first and second. In his next game, he doubled, tripled, and homered with the bases empty, but struck out with a runner on second. And in the game after that, he singled and doubled with the bases empty but grounded into a double play with a runner on first.

The pattern was pretty clear. Bases-empty Reddick looked like this:

While bases-occupied Reddick looked like this:

In those three games combined, Reddick went 7-for 10 with nobody on and 0-for-3 with a runner (or runners) on ahead of him.

Reddick is, on the whole, having a career year at the plate: He’s hitting .305/.358/.498, good for a 128 wRC+ (28 percent better than the league-average line). But that snippet of performance last week was Reddick’s season writ small. With the bases empty, Reddick has a 152 wRC+ (.319/.377/.565). With men on base, his wRC+ falls to 94 (.284/.330/.400). And with runners in scoring position, it sinks still further, to 76 (.268/.292/.393).

Maybe you’d rather see splits by leverage, a measure of how crucial and pressure-packed a situation in a given game is. In low-leverage spots this season, Reddick has a 149 wRC+. In medium-leverage spots, that falls to 106, and in high-leverage moments, it plummets to 58.

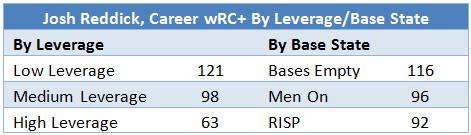

Over half a season, splits like these signify next to nothing. Reddick has made only 265 plate appearances this year, and when we start splicing that already-small sample, the sub-samples become too tiny to analyze. But those three games weren’t just Reddick’s season writ small; they were also a microcosm of his career. Here are Reddick’s career wRC+ splits by leverage and base state, over a nine-year stay in the majors encompassing close to 3,200 plate appearances.

Hitters typically perform slightly worse than usual in high-leverage spots, when pitchers may bear down or managers may bring in better arms. They typically perform slightly better than usual with men on and with runners in scoring position, when pitchers may be struggling and when fielders may have to play closer to bases, leaving wide swaths of space unguarded. To this point, though, Reddick has been dramatically worse than usual in high-leverage situations, and significantly worse when the bases weren’t empty. He has, to express the situation more simply, been incredibly unclutch.

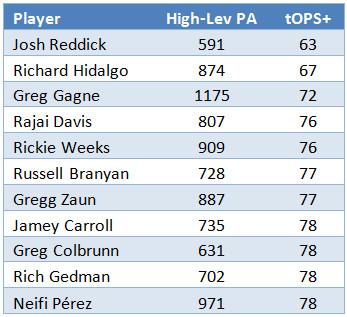

Among hitters with as many high-leverage plate appearances as Reddick has had, no one in Baseball-Reference’s records has ever struggled as much in those PAs relative to his overall offensive line. (In the table below, tOPS+ represents the player’s OPS in high-leverage situations relative to his overall OPS.)

Jeff Sullivan first drew attention to Reddick’s lack of clutchness in March 2016. Since then, three things have happened: First, Reddick has continued to be unclutch over an additional 181 games. Second, Reddick went from being on a bad team to being on good teams. And third, Reddick started to make much more money. The first development makes the latter two even more remarkable.

Let’s start with that continued unclutchness. FanGraphs also has a stat for this — intuitively enough, called “Clutch” — that weighs a player’s performance in high-leverage spots against his overall performance. According to Clutch, the consistency and magnitude of Reddick’s shortcomings in high-pressure spots set him apart from any other player.

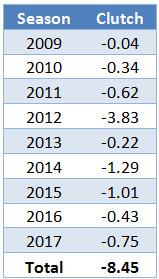

Earlier this week, members of the Angels argued that because of his clutchness, Albert Pujols has been more valuable to the team than his sub-replacement-level WAR this season would indicate. They’re right; Pujols leads the majors in Clutch this year, and he has a positive career Clutch score. But before this year, he had a negative career Clutch score, with eight negative Clutch scores and eight positive Clutch scores in his 16 previous seasons. That lack of a pattern is pretty typical; for most players, clutch performance varies unpredictably from year to year. For Reddick, it doesn’t: The 30-year-old has produced negative Clutch scores in every one of his MLB seasons so far, accumulating the worst career Clutch of any active player.

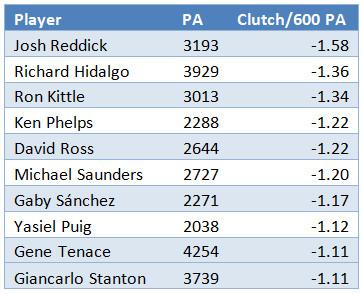

A streak of unclutch seasons is highly unusual over a career that’s lasted as long as Reddick’s has, but it isn’t unprecedented. Eight non-pitchers have had longer streaks, led by Sammy Sosa — owner of the all-time-lowest Clutch score — at 15 consecutive seasons. Reddick hasn’t played long enough to challenge that record, but he’s made the most of his time. His unclutch résumé includes the second-worst single-season Clutch score in FanGraphs’ records, which extend to 1974. That disaster came in 2012, when Reddick hit .296/.349/.550 (146 wRC+) in low-leverage opportunities and .192/.288/.346 (52 wRC+) in high-leverage spots. On the career level, no player with at least 2,000 career plate appearances comes close to matching Reddick’s negative Clutch on a rate basis.

It isn’t easy to pinpoint the root of Reddick’s high-leverage performance problem. The GIF below compares Reddick’s career plate-discipline stats in high- and low-leverage spots (through Tuesday) to the league’s over the same span.

It doesn’t appear that Reddick’s plate discipline has broken down in high-leverage situations. His swing rate in high-leverage spots has increased slightly more than the rest of the league’s, but only on pitches inside the strike zone; his chase rate has actually decreased when the pressure is on. His strikeout-to-walk ratios have been almost identical. The differences seem to have come in how hard he’s hit the ball, and how often it’s flown over the fence. Reddick’s career hard-hit rate in low-leverage situations is more than five percentage points higher than the corresponding rate in high-leverage situations, and his low-leverage home run–per–fly ball rate is almost twice as high. Both of those differences are much larger than the league-average splits.

If we factor in the context of when he has and hasn’t come through, Reddick’s unclutchness significantly alters our perception of his value. As I’ve mentioned, Sosa was, by the numbers, extremely unclutch. So were Mike Schmidt, Jim Thome, Alex Rodriguez, Gary Carter, and Barry Bonds. All of those players, though, were Hall of Fame– or near–Hall of Fame–caliber performers, and none rivaled Reddick’s unclutchness on a game-by-game basis. Even after taking their modest (relative to Reddick) unclutchness into account, they were still superstars.

Reddick isn’t nearly the player those elites were. His career WAR is 17.5, which translates to 3.3 WAR per 600 plate appearances — not star-level production, but solidly above average. Penalize him for his lack of clutchness by using a substitute for WAR that takes timing into account, though, and his career WAR would fall by more than a quarter, lopping off approximately one win per 600 plate appearances and making Reddick look roughly average. Consider also that Reddick’s defensive stats have declined in recent years, and that because he’s had trouble staying healthy and is sometimes platooned, he’s batted 600 times in a season only once. Really, then, the non-clutch-based expectation for the current Reddick is that he’s roughly an average player. In the worst case, which treats his lack of clutchness as a permanent part of his game, he’s worse than that.

So what is Reddick really worth? We can’t say with certainty, but MLB teams seem to have made their stance clear. At last year’s trade deadline, the Dodgers acquired Reddick (along with pitcher Rich Hill) in a trade with the A’s. In 43 career postseason plate appearances prior to last year, Reddick had hit .211/.302/.395, but the Dodgers wanted him despite being bound for the playoffs. (He went 8-for-26 for Los Angeles in the first two rounds of the playoffs, bringing his career playoff line to .250/.314/.359 — significantly worse than his regular-season line, but not extraordinarily so, in light of October’s increased competition.) And in November, the Astros — another presumptive playoff team — signed Reddick for four years and $52 million — as Sullivan wrote then, “the going rate for a roughly average player.”

If there were such a thing as an unclutch player, his stats would look like Reddick’s. Yet two contending teams have given up prospects or payroll to employ him, thereby tacitly supporting the position that Reddick isn’t forever unclutch. In fact, one Astros source told me that Reddick’s history of historic clutchness didn’t even come up in the team’s discussions about whether to sign him.

There are a few reasons teams may have overlooked Reddick’s high-leverage failings, intentionally or otherwise. For one thing, while leverage may accurately capture how important and high-pressure a situation seems to be in the moment, it doesn’t always perfectly reflect value to a team in retrospect. On May 29, for instance, Reddick drew a walk to lead off the top of the eighth inning with the Astros behind by six runs. In the moment, it looked like a low-leverage plate appearance. But the Astros went on to score 11 runs in that inning, taking the lead and holding on for the win. With hindsight, Reddick’s walk was crucial.

It’s also possible that teams haven’t put much stock in Reddick’s splits — or even noticed them — because ignoring those splits is smart in almost every case. Just to make the majors requires excelling against stiff competition under intense scrutiny in front of large crowds, which means that most players prone to falling apart under pressure never get the call. Every big leaguer has passed that test, which suggests that the variation in clutchness at the sport’s pinnacle must be relatively small. Buying into a player’s record of clutchness or unclutchness, then, would likely lead to more mistakes than successes. Reddick’s stats may suggest he’s an outlier, but he certainly doesn’t seem overwhelmed by big moments; in May, Astros manager A.J. Hinch called him “fearless.”

More important, perhaps, is the fact that clutchness and unclutchness take so long to detect. Although research suggests that those attributes exist, it also suggests that the differences are small enough, and the stats noisy enough, that clutchness shouldn’t enter into teams’ decision-making because it can’t be counted on to continue. To borrow (and slightly tweak) another idea from Sullivan, I assembled a list of players since 1974 who made at least 2,000 plate appearances through their age-29 season, as Reddick had when Houston signed him. Then I narrowed the list to players from that group who also went on to make at least 1,000 plate appearances after age 29.

The least-clutch 25 players remaining in the through-29 sample averaged minus-0.92 Clutch/600 PA over that span. After age 29, those same 25 players averaged minus-0.27 Clutch/600 PA — still unclutch, but not by nearly as much. In most cases of early-career unclutchness, teams would be much better off assuming average clutch performance going forward than they would assuming that a player’s previous unclutchness would be sustained. That’s encouraging news for Reddick, as much as his high-leverage struggles have stood out.

In the near future, wearable technology may take the guesswork out of the discussion of clutch; this year, MLB approved Whoop biometric monitoring devices for in-game use, which would, in theory, allow teams to analyze a player’s heart rate in high- and low-leverage scenarios and identify abnormal fluctuations on a physiological level. We don’t know what Whoop would say about Reddick, but based on his seasonal slash line, the Astros have probably been pleased with their decision to spend. In the time it took me to write this article on Wednesday, Reddick drove in three runs on three hits, two of which came with runners in scoring position. In the past decade, Reddick has been baseball’s least-clutch player. In the past day, he’s Houston’s RBI leader.

Thanks to Jonah Pemstein and Neil Weinberg of FanGraphs for research assistance.