Even before it began, World Series Game 2 was expected to be about Cubs starter Jake Arrieta’s ability to put pitches where he wanted to. “If he’s throwing his fastball where he wants early in this game tonight, he’ll pitch deeply into the game,” said his manager, Joe Maddon. A few hours later, in the first inning, Fox announcer John Smoltz warned the world of wildness ahead: “Because his mechanics are so unorthodox,” Smoltz said, shortly before Arrieta (who later said he was “overly amped up”) threw six consecutive balls, “the mechanics can leave him for periods of time.”

Later in the game, Arrieta’s command was still a subject of discussion, but the comments came with increasingly positive spin. By the fifth, play-by-play man Joe Buck announced that Arrieta had “been just wild enough that these Indians hitters have not been able to settle in on anything.” Between the two broadcast comments, Arrieta went four-plus innings without allowing a hit, which is one way to make an intermittent lack of command look like a virtue.

Arrieta’s no-hit bid continued for 5 1/3 innings, until a Jason Kipnis double broke it up. One out later, Kipnis scored on a wild pitch that went to the backstop, perhaps the only instance in which Arrieta missing a spot actually came back to bite the Cubs. Command is tough to evaluate in a rigorous way, because it requires us to interpret not only location, but intention. But both stats and scouts have offered solutions. Sportvision’s COMMANDf/x system, for instance, uses the same cameras and computers responsible for real-time pitch-tracking to detect the catcher’s glove — admittedly, an imperfect proxy for the intended target, since catchers don’t always hold their gloves where they want the pitch — at the moment the pitch is released. The distance between the target and the pitch’s eventual location is one way to quantify command.

Each of the blue dots on the COMMANDf/x graph below represents a start; the red lines mark seasonal averages. According to Sportvision’s data, Arrieta’s pitches did miss slightly more, on average, in 2016 than they had in the previous two seasons. (A graph of command on sliders only — the pitch that seemed to suffer the most from his mechanical slump — looks almost indistinguishable from the image of all pitches combined.)

On the other hand, they also missed by more in 2015, when Arrieta was almost unbeatable, than they did in 2014, when he was merely very good. Maybe that’s because he threw harder in 2015 than he had before, which may have made his pitches more difficult to command. What we can say, based on the info we have, is that Arrieta’s command didn’t always dictate how well he pitched. In analyzing the numbers, I made no attempt to control for ballpark or opponent, but on a start-to-start basis, there was no real relationship between Arrieta’s game score and his average miss distance, as measured by Sportvision.

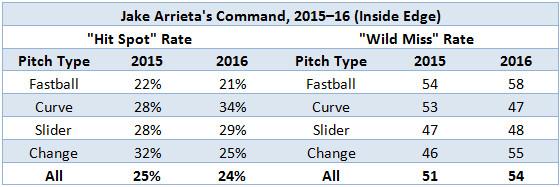

Command data from Inside Edge, collected via video scouts, tells a similar story: Arrieta may have had a greater tendency to miss badly this season, but his overall miss rates look like a push.

Talk of command continued even after the Cubs sealed their 5–1 win on Wednesday, because Arrieta’s sterling results — two hits, three walks, and six strikeouts in 5 2/3 frames — resolved the uncertainty for only one night. Sometimes Arrieta is wild and it works; sometimes he’s wild and it doesn’t. Sometimes we see him flip from spotty to pinpoint in the same start, as he did during Game 2, when he found his range after many early misses, but never looked Kluberesque. And even in the second half of the season, when Arrieta stopped seeming automatic, he was unquestionably better than Cleveland’s Game 2 starter, Trevor Bauer. Last October, a previously unbeatable Arrieta ended his season with two beatable starts; this October, a more beatable Arrieta’s (probably) penultimate start was, in effect, almost flawless. In Game 2, the unpredictable pitcher went the Cubs’ way.

“I think he carries his backpack around with his drones and does his thing,” Andrew Miller said about Bauer before the game. In theory, Bauer’s “thing” should have made him an unfavorable matchup for the Cubs. The Cubs succeed on offense, in part, by swinging selectively; during the regular season, only six teams swung less often, and only three teams swung less often at pitches outside the strike zone (despite the best efforts of Javier Báez). It follows that the Cubs should punish pitchers who live outside the strike zone (and rely on teams to chase), and struggle somewhat against guys who pound the plate (and potentially pick up called strikes against the Cubs’ patient bats).

Although Bauer will walk batters, it’s not because he can’t find the strike zone. Bauer’s rate of pitches inside the zone ranked among the top 17 qualified starters this season — depending on the data source, either immediately behind or well ahead of the Indians’ noted nonwalker, Josh Tomlin. Bauer issues walks under normal conditions not because he’s wild, but because when he does go outside the zone, he has trouble tempting hitters to chase. The Cubs don’t chase anyway, so their selectivity doesn’t really rob Bauer of a strength.

That’s the theory, anyway. It sounds great, except that the stats don’t support it. I looked up all the pitchers who faced the Cubs during the regular season, and I compared their weighted on-base average allowed (a stat on the OBP scale that encompasses the sum of a hitter’s performance) against all teams to their wOBA allowed against the Cubs, with both figures weighted by batters faced. The numbers are below.

Both strike zone finders and strike zone missers were worse against the Cubs, because the Cubs are good. But strike zone finders such as Bauer, who are better to begin with, suffer more against the Cubs, relative to their typical performance. The moral of the story is that nothing works consistently against the Cubs (and also that it’s easy to waste time in Excel trying to twist baseball stats into neat narratives).

Whether Bauer’s typical approach predisposed him to be worse against the Cubs was probably outweighed by Wednesday’s unique conditions. This wasn’t the typical Bauer, but a Bauer pitching with a sutured fifth finger, in temperatures that slowed Terry Francona’s flow and made some players opt for time-honored fall fashion choices.

Whether due to the finger, the weather (which Arrieta, well, weathered), or some butterfly effect circumstance beyond our ken, Bauer’s curveball lacked its usual spin, which could only have compounded the separate problem that the Cubs may have known the curve was coming. It took Bauer 87 pitches to get through 3 2/3 innings, and while he allowed only two runs, that advantage teed up the Cubs for an endgame like those the Indians have enjoyed for most of this month, while exposing the Indians’ bullpen’s underbelly. Arrieta-Montgomery-Chapman isn’t as intimidating a sequence as Kluber-Allen-Miller, but it was close enough to work equally well for one game.

On a night when observers studied Doppler radar maps as intently as they had pored over pitch plots in the previous game, the Cubs made no concessions to expediency. Instead, they clung to their key to the game.

They drew eight walks and made the Indians throw 196 pitches (32 to Anthony Rizzo alone), stretching the game time to an almost-disastrous 4:04. Even with slowpoke pitcher Pedro Báez nowhere near a mound, a combined 20 strikeouts and five mid-inning pitching changes made what should have been a showcase into something of a slog. Kyle Schwarber’s best efforts notwithstanding, no one who wasn’t already a baseball fan would have become one due to this game.

Cleveland right fielder Lonnie Chisenhall played a part in two of the Cubs’ first three runs. In the first inning, he threw to the second-base bag instead of the cutoff man on a Rizzo double, allowing Kris Bryant to run home; in the fifth, he misplayed a Ben Zobrist double into an RBI triple. (If the former play had happened against the Royals last year, we’d be in for a few articles — and podcasts — about how their advance-scouting acumen had tipped them off to where he would throw.) Schwarber, who returned in Game 1 from a knee injury suffered in April, delivered the other early runs. The stereotypically slugger-ish Schwarber, whose presence in the series was so unexpected that we would have felt cheated out of a storybook ending if he wasn’t also its star, continued to make skipping the season seem insignificant. He drove in two runs on singles (one of which came on 3–0) and later added a walk, after warming his already hot bat before an extremely unsafe-looking space heater.

The off-day story will be whether Schwarber, who hasn’t been medically cleared to play defense, can take a turn in Wrigley’s left field (tied with Progressive Field’s for fourth-smallest in baseball) in Game 3, giving the Cubs a big offensive boost against the right-handed Tomlin relative to their righty outfield options or the still-slumping Jason Heyward. A few days ago, the Cubs seemed insane for wanting to have him hit. If they think he can field, I won’t tell them they’re wrong.

In their pregame press conferences, Francona and Maddon made baseball strategy sound simple. Asked to explain his postseason success, Francona said, “I think what it is is I’ve been fortunate to be around some really good players. In baseball, you can’t make your team better than they are.” Maddon echoed his sentiments: “There’s nothing you can do about [your opponent’s plan]. You get your guys ready to play, you present your best lineup, and you go.”

Both managers were probably underselling their skills. Through the first two games, though, their decisions haven’t defined the series. Each has made debatable moves: benching Heyward; starting Jorge Soler because of Bauer’s reverse splits; using Miller and Allen as much as the Indians did in Game 1. We just haven’t had to debate them, because the best players on two of baseball’s best teams — Kluber, Miller, Francisco Lindor; Arrieta, Rizzo, Schwarber — have made nitpicking unnecessary. Maybe it’s better this way.

Thanks to TruMedia, Rob Arthur of FiveThirtyEight, Kenny Kendrena of Inside Edge, and Graham Goldbeck of Sportvision for research assistance.