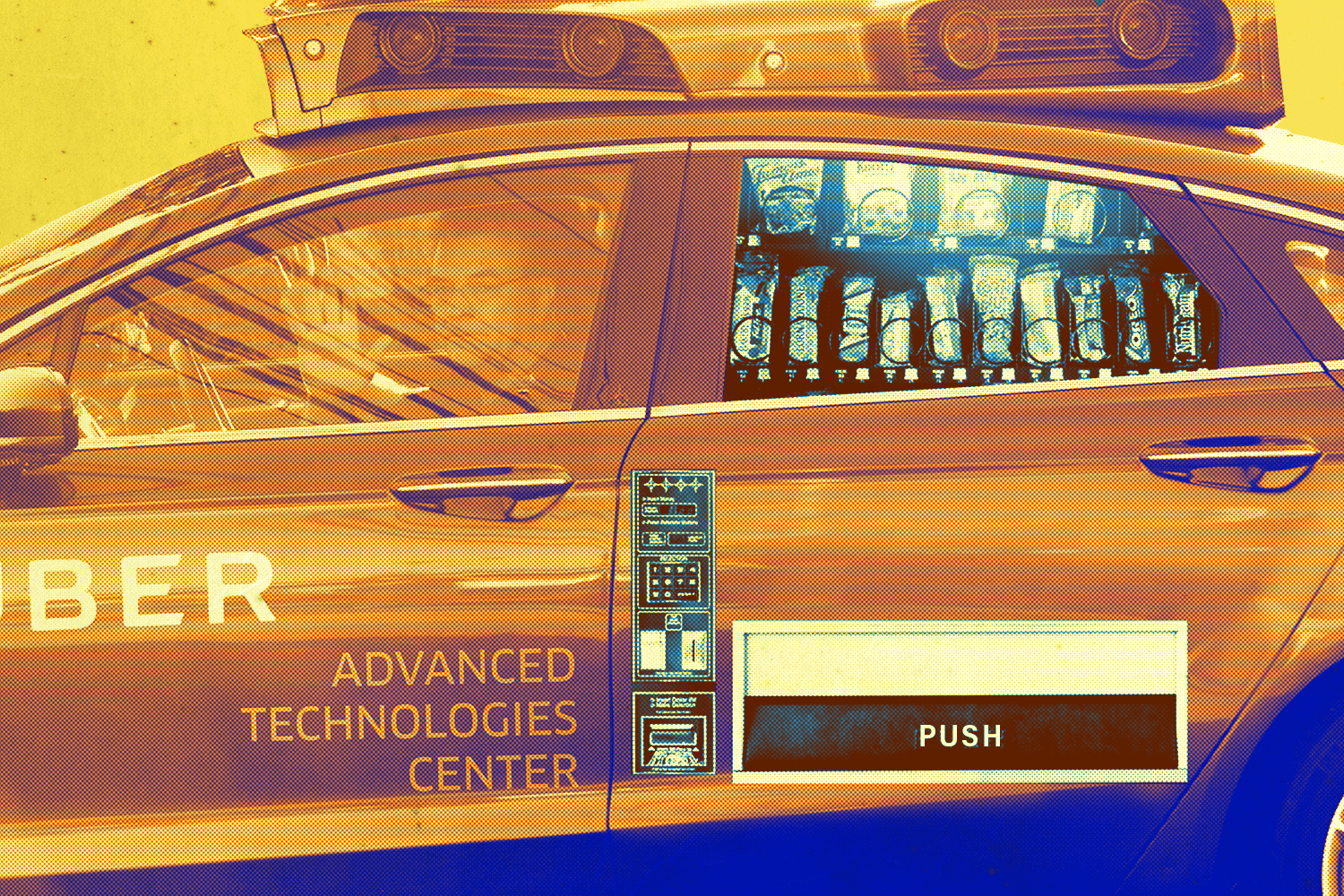

The gig economy continues to grow in crafty, concerning ways. Earlier this week, a startup called Cargo raised $5.5 million in a seed round to transform the cars of Uber and Lyft contractors into roving convenience stores. The company hands out portable vending machines to rideshare drivers, who use them to sell candy bars and chips. These snack vessels are also used to give out free promotional products for marketing purposes. Drivers get a 25 percent commission for each paid order plus a $1 base commission fee. All of it sounds pretty practical! But it also underlines an interesting trend: what feels like the never-ending chain of side hustles atop side hustles.

There are already indications that startups have glommed onto our homes, offices, and social media accounts to squeeze as much money out of every willing individual possible. Hell, Dave Eggers wrote a pretty accurate, if crude, technophobic novel about all this in 2013! So it’s worth asking: Is there a limit? — Alyssa Bereznak

How many side hustles can we stack on top of one another until the whole thing topples down?

Molly McHugh: Right off the bat, this idea bums me out because I feel like that’s the end of free water in Ubers/Lyfts, and having that available is just a blatantly good idea. I really hate the notion of being asked whether I want water and then being charged $1.

Kate Knibbs: When it comes to exploiting workers, I’m pretty confident in various tech companies’ abilities to stuff as many different gigs into the world as they possibly can. That said, if I can order a Lyft and get a slice of pizza handed to me for a few extra bucks … I’m gonna eat the pizza.

Bereznak: How many more will make it into an Uber, do you think? Will it get to the point where they’re trying to sell us timeshares and knife sets?

Michael Baumann: In other words, will deregulation of the cab industry make Uber look like a deregulated airline? What would you call Skymall for an Uber?

McHugh: It’s gonna be called UberMall.

Victor Luckerson: The long game is definitely to monetize Uber-Lyft in all sorts of ways, especially once they have driverless fleets. Ultimately it will be the companies themselves implementing and profiting from the “side hustles.” Sorry, Cargo.

McHugh: Yeah, I think that’s the long-term result here; companies like Cargo will pop up but Lyft and Uber will start their own versions and shut down the competition. Hi, Uber Eats.

Luckerson: Airbnb is already doing this by letting hosts also market “experiences” like cooking meals or taking visitors to live shows.

Bereznak: That concerns me, though. There’s already been so much discussion about how much control these major companies have over their contractors that it seems wrong to me that they would have dibs over these spaces that they don’t even technically own, clean, or maintain.

Baumann: I thought that was the point of the gig economy — reaping the profits of traditional business, but getting workers to provide the raw material.

Bereznak: I mean, yes, but I am not happy about it!!

Baumann: Soon we’re gonna be signing up for shifts at textile factories but we’re gonna have to raise our own sheep during off hours.

McHugh: Right. It’s going to contribute to a potentially really disenfranchised/depressed workforce. No upward mobility.

Baumann: The disenfranchisement element is most troubling to me, because you’re going to — well, I guess we already have this — have people who don’t make enough from their 40-hour-per-week day jobs (which get stretched into 45 or 50 hours per week) to maintain things like a house or a car, which are supposed to be safe personal spaces and the signifiers of a middle-class American life. So they spend what’s supposed to be their leisure time, time spent fulfilling what Marx called their species-being, renting out those same safe personal spaces to make ends meet.

And I don’t see a way around that as long as the American economic system privileges the welfare of “business,” whatever that means, over the welfare of the individual. It’s only gotten worse since 2008. Oh wait, this is supposed to be a tech chat.

Bereznak: Baumann gets a gold star for making the first Marx reference in this roundtable.

Baumann: Knibbs came out strong. I had to beat her to the punch.

Knibbs: Comrades!

Lawmakers are obviously way behind in regulating this stuff. I know this is really a question about the future of the world in some way, but do you expect that there will ever be a breaking point that pushes forward some significant legislation in this area?

McHugh: I sort of think there will be some empathy breakdown, like when we realized maybe we SHOULDN’T have children working in industrial factories? Something dramatic will happen or begin to manifest and there will be more regulations on contractors.

Baumann: Well — and I’m not being snarky, I’m really asking here — in which sectors of American life has the government regulated away avenues to immense wealth for the few at the peril of the many? Recently.

McHugh: Right, it’s a bleak outlook. I guess I think that even if more regulations existed, we’ve already seen that companies like Uber will ignore them.

Luckerson: Regulation is much more likely on a local level. London banned Uber for general bad corporate practice in the fall, and cities around the country are trying to curb Airbnb.

Baumann: But for almost everyone who cares about worker exploitation in theory, there’s a huge information gap. I recently had a conversation with two friends who are smart, well-read, white-collar liberals who use Uber all the time and they’d never heard the term “gig economy.” (And after my 10-minute tirade about the alienation of labor, I bet they wish they never had, but still.)

Bereznak: On the customer level, I also envision that the experience of riding in an Uber car may become so cannibalized by other advertisers and side hustles that it’ll be akin to walking down the Vegas Strip. And these companies will then offer a version of their service free of ads, sort of like Hulu.

McHugh: Oh god. A tiny Vegas housed inside an Uber car? That’s my nightmare. I’m imagining a street performer in the front seat as well.

Bereznak: Did not mean to trigger you, Molly. I know a few of us here are still recovering from CES.

Baumann: I take it back — the way to get people to revolt against this stuff is to put street performers in the front seat of every Uber car.

Knibbs: An Uber driver tried to sell me a CD of his music once. It was a dark moment, I think for both of us.

McHugh: An Uber driver tried to sell me coffee that makes you skinny. He made it himself. It was in these little packets. He also said The Ringer should hire him to write! It was a long ride.

Bereznak: Readers, if you want a full repository of these experiences, please check out the story I wrote on Uber side hustles last year. This actually brings me to my next question, which is:

What is the most absurd byproduct of the gig economy that you’ve encountered in real life?

Luckerson: Definitely staying alone in multiple two-story party houses in Nashville for a story about Airbnb. Those houses are not actually part of the “gig economy,” but they use the altruism inherent in gig-economy marketing and platforms to advance their business.

McHugh: I ordered an on-demand pawdicure for my dog. There’s an app that will send someone to your house who will trim your dog’s nails for you. I felt like a true piece of shit for doing this and paying for it, but it was way easier than doing it myself or taking the time to take him in. Just so it’s clear, THEY call it a pawdicure, not me.

Bereznak: A noble confession, Molly. I, too, have often felt like a piece of shit for ordering gig-powered services to my home out of laziness.

Knibbs: One time my Airbnb host locked me out and fell asleep, so I had to get a hotel. Then she shut her account down so I couldn’t leave a bad review.

Luckerson: The ultimate hustle.

Knibbs: I couldn’t really be mad.

Bereznak: A few months ago I was at a tech company’s extravagant party, and they had a Glamsquad station where someone would give you a manicure. My manicurist spent the whole time telling me about how she and her peers were struggling to organize against the company to demand for better treatment and pay. I left very depressed.

McHugh: Yeah, the at-home beauty market seems like it’s a bummer.

Do you think some of this bleeds into our social media accounts and the idea of normal people becoming “influencers”? This Outline story about how Twitter parties are the new Tupperware parties comes to mind. How do you envision this area might evolve?

Knibbs: Dear lord. I’ve never heard of “Twitter parties” until now, but it sounds extremely dorky. One of the things that bums me out the most about the rise of “influencers” is the idea that you turn your public self into a brand.

Bereznak: Right, and that combined with however many gigs you’ve collected sort of brings to mind the idea of a frantic one-man band who also sells merch and paints your nails.

Knibbs: I feel like it discourages people from changing their minds or experimenting, because they feel pressured to stay “on brand.” Also, it sounds like an absolutely exhausting lifestyle!!

Baumann: Or the antidote to crippling loneliness.

McHugh: Whoa, twist from Baumann!

Knibbs: Baumann … are you secretly an Insta-influencer?

Baumann: No, in order to do that I’d have to be paid. But hey, inquire within if you want to attach spon-con to my feed of baking projects and pictures of my cat.

Bereznak: Baumann is secretly in the pocket of Big Cowboy Boot. Exhibit A, from our “Best Things We Bought This Year” post.

Baumann: Have you bought boots for yourself, Alyssa?

Bereznak: Yes.

Baumann: And yet you mock.

Bereznak: Lol.

Baumann: The good news is soon you’ll be able to rent my boots for $4 an hour on Travis Kalanick’s new app: Bootz.

Bereznak: Where do I sign up?