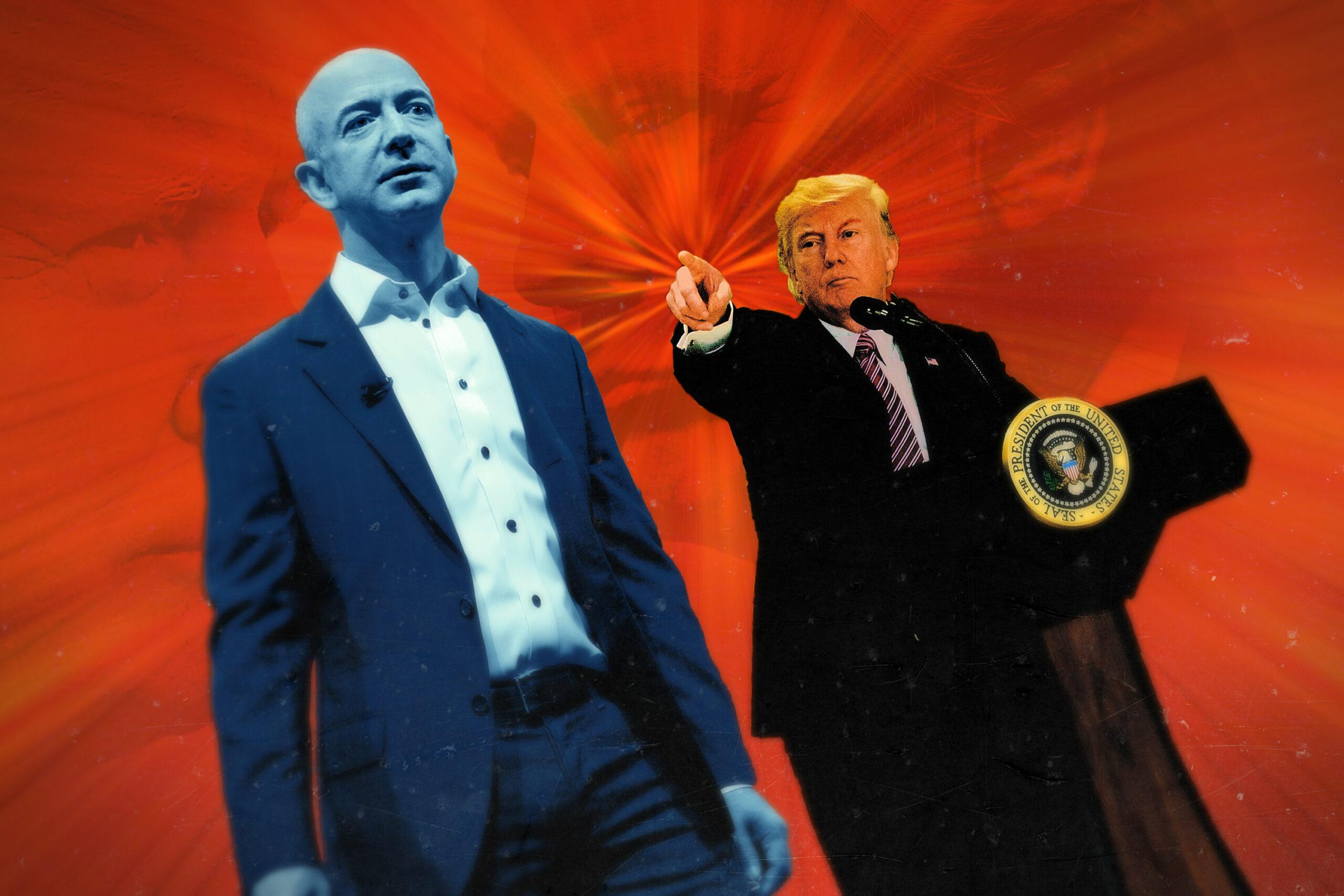

When an extremely muscular Jeff Bezos strutted out of a tech conference in Sun Valley, Idaho, and onto our Twitter timelines in July, the internet had a lot of questions. Why was bookish little Bezos suddenly so swole? My theory: He’s preparing for his inevitable showdown with his powerful political adversary, Donald Trump.

Last week, the president sent out an angry tweet about Amazon, complaining that the company is hurting “tax paying retailers” around the country. It’s hardly the first time Trump has singled out Amazon in particular among the major tech giants, and it probably won’t be the last. But in the seven months since his inauguration—and especially since his handling of the tragedy in Charlottesville—Trump’s relationship with corporate executives has soured. It’s no longer clear that Twitter will be an effective bully pulpit to compel Amazon or any other company to do the president’s bidding, if it ever was at all.

The Trump-Bezos schism seemingly began on December 7, 2015, when Trump tweeted that The Washington Post, purchased by Bezos in 2013, loses money and “gives owner @JeffBezos power to screw public on low taxation of @Amazon” (the Post claims to be profitable). Bezos took the dis as a badge of honor and joked that he would save a seat for Trump on one his space startup’s rockets. The internet laughed, and much light-hearted content was aggregated. It was a simpler time.

A year later, Bezos found himself schlepping to Trump Tower to kiss the ring of the president-elect in the first of a series of meetings between Trump and tech’s most powerful executives. While Bezos called that first meeting “very productive,” the look on his face at his June reunion with the president was the distant, glassy-eyed stare of someone who’s made a huge mistake. Now that Bezos has transformed into a muscle-bound, sunglasses-wearing renegade who plays by his own rules, his relationship with Trump could become even more strained.

Trump’s complaints against Amazon are mostly old-hat criticisms that won’t sway many people’s opinions of the company. The president grouses that Amazon doesn’t charge sales tax on its products, giving it an unfair advantage over brick-and-mortar stores, when in reality the e-tailer does now charge a sales tax in every state where one is on the books (third-party vendors on Amazon can still forego the tax). Trump calls The Washington Post a lobbying tool to help Amazon not pay taxes, but this criticism is almost certainly driven by the Post’s dogged critical coverage of the White House. He calls Amazon a job killer, but he also took credit for its announcement earlier this year that it would add 100,000 additional full-time employees. The ways in which Amazon is restructuring labor and commerce deserve careful scrutiny, but they don’t fall into a “Amazon bad–Trump good” binary. “Trump is not the first person to complain about Amazon,” says Brayden King, a professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. “Because Bezos is such a visible figure, it’s easy to point at him as the source of some of Trump’s problems.”

The one Trump accusation that could potentially threaten Amazon’s future is the claim that the retailing behemoth is a monopoly. During his presidential campaign Trump said Amazon has a “huge antitrust problem because … Amazon is controlling so much of what they are doing.” As the tech sector’s most powerful companies vacuum up more market share and influence, worry about antitrust litigation is on the rise (especially in Europe). An antitrust reckoning seems inevitable, especially for a company whose mission statement includes, “[building] a place where people can come to find and discover anything they might want to buy online.”

A straightforward argument that Amazon is putting mom-and-pop stores out of business due to low prices or the lack of sales tax, as Trump rails against in his tweets, would likely go nowhere in an antitrust case. “My guess is that there is no specific product that Amazon sells … in which it has a monopoly as currently defined in antitrust law,” says Harry First, a law professor at New York University. “That requires roughly 60, 65, 70 percent of a market.”

First says that while the power of Amazon might fit Trump’s idea of a monopoly—a very large, powerful company—a firm needs to engage in activity that could potentially harm consumers in order to be threatened by antitrust litigation. Though it generated $80 billion in sales last year in North America, Amazon has largely managed to avoid antitrust scrutiny because its core strategies—offering competitive pricing and a cheap bundle of services via Amazon Prime—appear to help consumers rather than hurt them. Even in markets where Amazon dominates, such as e-books, its consumer-friendly pricing makes it an unlikely antitrust target. In fact, it was Apple that ran afoul of antitrust laws by conspiring with book publishers to raise e-book prices above the rates Amazon had standardized.

But the view that anticompetitive behavior is largely driven by price is slowly changing. When evaluating Amazon as its own ecosystem—one in which Amazon can dictate prices via its product listings, control distribution via its fulfillment centers, and even manage a firm’s ability to exist online via its cloud computing services—the company is powerful on a scale rarely before imagined. Lina M. Khan, a legal fellow at the New America think tank, likened Amazon to a 19th-century railroad company in a New York Times op-ed. “By integrating across business lines, Amazon now competes with the companies that rely on its platform,” she wrote. “This decision to not only host and transport goods but to also directly make and sell them gives rise to a conflict of interest, positioning Amazon to give preferential treatment to itself.”

Of course, all of these nuances are unlikely to be of use to Trump, who tends to use simple, declarative public shaming and praise to try to influence business executives. Twitter has been his blunt instrument to telegraph his policy inclinations, but his methods have left a lot of confusion about how seriously to take his threats, and how much influence he intends to wield over the Department of Justice, which traditionally manages antitrust investigations independently. “A big question to which we do not know the answer yet is whether this president’s transparent approach, whether that will affect antitrust enforcement,” First says. “That’s something I think people in the antitrust community are quite worried about.”

Trump’s ability to influence the decisions of corporations through lightly informed bluster appears to be waning, though. In the wake of the violent white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, after Trump repeatedly equated the actions of racist hate groups with those of the counterprotesters who opposed them, the CEOs of PepsiCo, General Motors, Intel, and a variety of other blue-chip brands abandoned a pair of presidential advisory councils. CEOs finally seem less concerned with whether an angry Trump tweet will temporarily sink their company’s stock price and more worried about how their alliance with the president will affect their long-term perception among customers and employees. “Trump seems to have lost the business community before he lost the Republican Party,” King says. “He really has put himself in a position where he has few strong supporters. This is not the time for any leader in the business world or politics to draw closer to Trump.”

The president could still do a lot to dictate the future prospects of major companies, but more so through the people he appoints than through his own actions. Makan Delrahim, Trump’s appointee to lead the DOJ’s Antitrust Division, is awaiting approval from the Senate. As a longtime Washington player who served in George W. Bush’s Justice Department, he’s likely to sail through the nomination process. And while it’s not clear how Delrahim evaluates the complex and changing ways that America’s most powerful companies consolidate power, he’ll play a much larger role in deciding Amazon’s fate than Trump’s Twitter feed.