Rosalie Fish Wants to Be the Face of Change

She runs to spread awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous women, an epidemic that remains in the shadows despite ravaging communitiesBefore every race, Rosalie Fish stares at her reflection in the mirror. She pauses a few minutes and thinks of Indigenous women. Women who have gone missing, who have been murdered. Those whose names she knows, those whose names she’ll never know.

Aunts, cousins, neighbors, classmates. Women who had families, who had ambitions. Who had children, friends, dreams, desires.

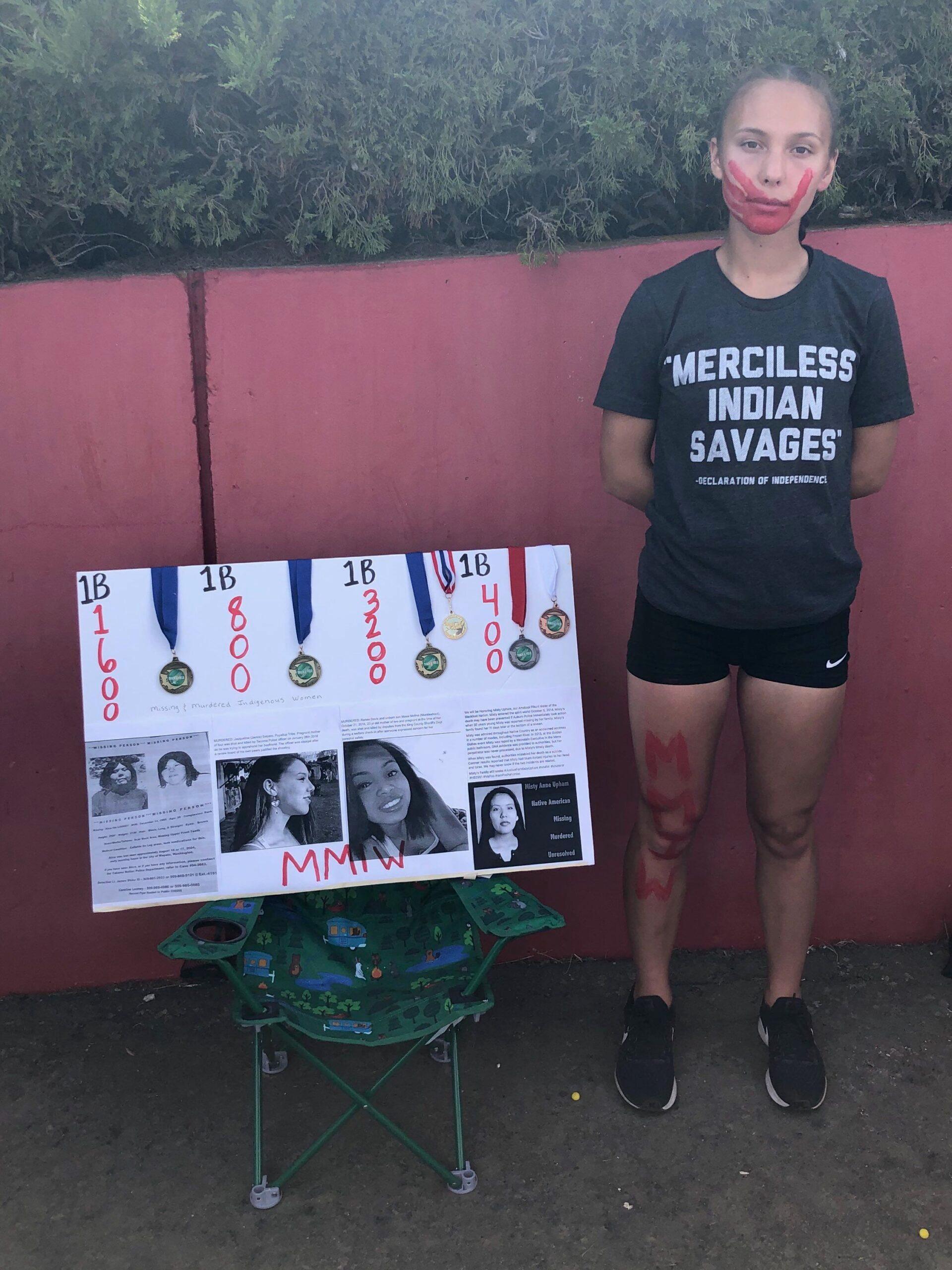

She paints a giant red hand across her mouth, stretching across her cheeks. Red is the color that spirits, that ancestors, can see, according to some Native traditions. The hand over her mouth is meant to represent and honor the Indigenous women who have been silenced through violence—sexual violence, physical violence, psychological violence—an epidemic that receives little national attention.

“I had always known I was a target,” Fish says.

When she closes her eyes, she can see the women’s faces. Sometimes Fish, a member of the Cowlitz Tribe and a descendent of the Muckleshoot Tribe, thinks of her aunt Alice Ida Looney. Looney disappeared when Fish was 2 years old, and was found deceased 15 months later. Fish also thinks of Renee Davis, a Native woman close to her family who was six months pregnant with her unborn son, Massi Molina, at the time she was killed. Her mind drifts to Misty Upham, the Native Hollywood actress who disappeared and was later found dead when Fish was around 12.

Fish started running to cope. To clear her mind. When she steps outside her home, past the pines and the large cedar in her front yard, to go running throughout the Muckleshoot Reservation, where she lives, in Auburn, Washington, she can briefly distract herself from the fear that pierces her: that as an Indigenous woman, she, too, could disappear.

She signed a letter of intent to compete for the University of Washington’s women’s track-and-field team as a transfer in January. She had led Iowa Central Community College to the National Junior College Athletic Association cross country title in 2019, and finished fifth overall at the National Half Marathon Championships in 2020.

“Resilience and self-belief are the two biggest predictors of success at this level, which bodes well for Rosalie,” says Maurica Powell, Washington’s director of track & field and cross country, who coaches Fish.

Fish is accustomed to being one of the only Native runners in her sport. Hearing racist comments as she runs, as she shines.

She runs to raise awareness for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) and Girls movement. Indigenous women on some reservations are murdered at a rate of more than 10 times the national average of other ethnicities, according to Department of Justice data from 2008. In the United States, murder is the third-leading cause of death among Native women.

More than four out of five Indigenous women have experienced violence. The perpetrators of this violence are often never held accountable.

In an analysis of the nation’s urban centers, the Urban Indian Health Institute division of the Seattle Indian Health Board reports that Washington state has the second most cases of missing Indigenous women. Seattle, which is about 30 minutes north of Rosalie’s home in Auburn, ranked first among cities nationwide.

That’s why Fish often asks friends to text her to let her know they’ve made it home safely when they go out at night. She leaves her phone’s ringer on the highest volume when she sleeps, just in case. And when she leaves her home to go run around the reservation, she sometimes leaves behind notes for her family that read:

“If I end up missing, I did not run away. And if something happens to me, and I lose my life, I did not take it.”

Fish draws inspiration from runner Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel, of the Kul Wicasa Oyaté/Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, who paints her own face as a prominent leader of MMIW. When Fish first saw Daniel, who ran the Boston Marathon wearing the red hand print, she was left in awe. Both women hope to bring awareness to the crisis of violence against Indigenous women, which is often undercovered by mainstream outlets.

“Our relatives go missing three times—in life, in the media, and in the data,” Daniel says. “And readers must also realize how prevalent this violence is, the jurisdictional loopholes that make it difficult to prosecute, the institutionalized racism that exists within law enforcement, the misrepresentation of Native peoples in the media, in school curriculums and stereotypes that all contribute to the normalization of racism we experience and erasure of Native peoples from almost every conversation we have today.

Our relatives go missing three times—in life, in the media, and in the data.Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel

“When I wear the red handprint, it is sacred to me,” Daniel continues. “It is not a fashion statement nor a political statement. It symbolizes the violence silencing our relatives’ voices.”

The first time Fish painted the handprint on her own face, as a senior at Muckleshoot Tribal School in 2019, she was terrified. Terrified at the negative reactions she knew she’d receive from spectators, opponents, officials. Sure enough, some said she should be disqualified from competition for deviating from uniform code. Others shouted from the stands:

“Hey, what’s on your face!”

“Look at her war paint!”

“That’s so stupid. Just run!”

But Fish can’t just run. Not when she’s experienced walking into her school’s girls’ bathroom and seeing “DIRTY INDIAN SAVAGES” written on the stalls. Not when she’s been rejected from some invitational meets despite boasting top qualifying times. Not when she lives in a world that often looks the other way when women who look like her disappear.

The first time Fish, whose friends and family call her Rosy, realized she was “different,” as she puts it, was in elementary school. She watched as members of her tribe performed traditional Coast Salish canoe family dances and songs on stage at a school event in Auburn. She walked up to join them, instinctively drawn to the beat.

Her shoulders, her waist, her feet, all knew what to do. Her head tilted back and forth, her smile drawn wide. Lost in song, she felt safe. Powerful.

She grew up hearing stories of how resilient her ancestors were. How she is a descendent of a vibrant people who persevered and danced, who sang and survived. She learned about her great-grandfather, George Cross Jr., and another family member, Henry KingGeorge, who were jailed for fighting discriminatory hunting and fishing laws. She felt proud when she heard those stories.

When she got off stage, though, her face flushed with embarrassment as her white classmates began to mock her. She regretted performing the dance and began to feel self-conscious. Ashamed. “For a really long time, I didn’t really want to embrace the fact that I was Indigenous,” she says.

Classmates continued to mock her as she got older. Attending a predominantly white high school, Auburn Riverside, for the first half of her freshman year, she often faced microaggressions and racist comments. She was sexually harassed, she says, as other students grabbed, pinched, and catcalled her. She felt violated, and blamed herself.

She felt isolated, not just in terms of her Indigenous identity, but in other aspects of her identity as well. “I had begun to realize that I was queer,” says Fish, who uses she/her pronouns.

Things at home weren’t much easier. At times, Fish’s stepfather would come home drunk, yelling. Fish suffered severe depression by age 14. She felt as if she would never belong at school, internalizing years of messaging that girls who looked like her had no place. She’d look at herself in the mirror, fixate on every part of her body, and think: There is nothing to love about me.

She ran occasionally, but didn’t yet consider herself a runner. Every day she felt more alone. Nobody wants to hear what I have to say.

She was prescribed antidepressants, but began excessively using them. She felt as if she didn’t have any value, as if she didn’t deserve to take up space. She felt hopeless, and tired. So tired.

Then she attempted to take her own life.

Fish hadn’t anticipated surviving. She was brought to the local hospital’s emergency room.

Autumn McCloud, her mother, fearfully waited outside her room. McCloud, a member of the Yakama Nation and descendent of the Muckleshoot Tribe, tried to reconcile the past, the present. Her daughter’s suffering, her own suffering. Old memories flooded McCloud: how scared she was of her own father, who heavily drank, so much that she and her siblings would hide in the laundry room, waiting until his rage subsided.

She thought about how she tried so hard to give Fish a better life, having gotten pregnant with her at 18. “I tried to make things better,” McCloud says of her family’s relations. “I tried to be the peacekeeper.” And there she and her daughter were, all these years later, trying to understand how patterns repeated themselves. Patterns McCloud now realizes stem in part from the boarding schools that previous Native generations, including her own family, were forced into.

Thousands of Indigenous children in the U.S. and Canada were sent to these boarding schools in the 19th and 20th centuries to erase their traditions, languages, and cultures. Abuse of all kinds was rampant in the schools. Large numbers of children did not return, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; more than 4,100 were confirmed to have died at the schools. The commission, established in 2008, called the practice cultural genocide. In May, the remains of 215 children’s bodies were found buried at a former Canadian school.

Fish says her great-great-grandparents suffered physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the boarding schools—trauma that would become braided into the fabric of her family for decades to come. “We are lucky to even be in existence,” McCloud says.

After everything her family has endured, McCloud worried they could lose Rosy, too, after she attempted to harm herself. “I didn’t feel safe bringing her home,” McCloud says.

So they stayed at the hospital longer. An elder on the reservation, a man who performed spiritual work, came by to visit Fish. He was a friend of McCloud’s grandfather—Fish’s great-grandfather—and wanted to see if he could help nurture her spirit.

“Rosy,” the elder said, “losing you is one of our biggest fears.”

She looked up at him, taking in the word our.

“I don’t know if we can handle another child in the graveyard,” he said.

Something in her felt seen. Accounted for. “He opened my eyes,” Fish says, “to seeing myself not as an individual who was alone, but someone who was part of a community.”

Once Fish returned home, she saw the way her mother, her siblings, her extended family, her community, banded together for her. They told her that she was worth living for. Worth loving.

She felt the kindness, the warmth, of her aunts and of her grandmother, in the smallest of moments, like draping a coat over her when they sensed she might be cold. “When I saw my community and my family doing everything they could to make sure I was all right,” Fish says, “it was so overwhelming I almost had no choice but to feel love for myself.

At that time when I didn’t really feel like I had the strength or confidence to live for myself, I was able to find a way to live for others.Rosalie Fish

“At that time when I didn’t really feel like I had the strength or confidence to live for myself, I was able to find a way to live for others.”

She started running every day, thinking it could help calm her down. Center her. It had been a hobby, not a refuge. But now, it was slowly becoming so much more to her. It made her feel safe. Seen. It brought her joy, peace. A sense of belonging. So she’d run. Run through the reservation, past the cedars, the neighbors waving as she whirled by. She became obsessed with the feeling of the wind hitting her face as she picked up speed.

She was a natural distance runner, able to run for miles and miles at a time. First two, then three, then more. She didn’t seem to tire. As she built up even more stamina, more strength, she wanted to keep running, pushing past her limits.

Running gave her purpose. It became a coping mechanism as she began to focus on her mental health. Talk to a counselor. Slowly, she started to appreciate her body; the miraculous way bones and joints and muscles and organs worked together to propel one foot in front of the other, mile after mile.

To run was to look at the past, to look at everything trying to hold her down, and say: I am still here. We are still here.

Fish wanted a fresh start, so she transferred to Muckleshoot Tribal School. Though she was learning alongside other Native students, she competed in league meets against the biggest schools in the area. She was almost always the only Native runner.

Fish’s coach, Mike Williams, would try to enter her into competitive invitational meets, but would often be denied. “Well, I’ve never heard of Muckleshoot Tribal School,” Williams remembers hearing from officials. Williams is not Native, but he’s been a part of the Puyallup tribal community for 15 years.

One official asked whether Fish even owned a uniform, as if she couldn’t possibly have one because she lives on a reservation. Other times, officials suggested she run in the junior varsity division, despite her varsity qualifying times. “It was really frustrating,” Williams says.

Fish grew even more determined, running seven days a week. “That was the only way I could prove to the people who had prejudice toward Native Americans that we were perfectly capable of competing,” she says.

Fans continued to hurl racist comments at her, especially when she started painting the red handprint on her face before races. She’d find other slurs and hateful messages on bathroom stalls at different meets.

Sometimes Fish’s confidence would falter. Do I really deserve to be here? Williams would remind her: “You belong. I know you can win. Show them you can win!”

You belong here. You deserve to be here, she’d repeat to herself. Again and again.

She began to shine, winning numerous Washington state titles at the 1B level, including the 800 meter, 1,600 meter, and 3,200 meter as a senior in 2019.

She felt pride when she would beat girls from much bigger schools, hearing, “Rosalie Fish, Muckleshoot, in first place!” every time she came around the drag. “Everybody was like, who is this?” Williams says.

Winning state meant a great deal to her, because she won the sportsmanship medal there, too. She dedicated the 3,200-meter race to the memory of Renee Davis.

Fish cherished how women in her community rallied behind her. And slowly she began to come out of her shell. Trust people. Once, before a race, a staffer at her school named Jenel Hunter came up to her, and saw that Fish hadn’t put her hair up for the meet. Hunter smiled. “Don’t you have a race coming up?”

“Yeah,” Fish said.

“You should have your hair braided. I’ll do it.”

It was freeing, feeling loved.

But fear was never too far behind, always chasing her no matter how fast she ran. She and a high school friend went to the mall one afternoon and spotted an unhoused woman asking for a few dollars. Fish only had a credit card on her. “Sorry,” Fish said, “I don’t have anything.”

She took about three steps in the other direction, and a familiar anxiety seized her. What if she’s in danger? What if she needs a bus ticket? What’s going to happen to her? Fish sprinted back to her car, rummaging through her things to find any kind of money. By the time she had gotten back, the woman was gone.

Fish looked grief-stricken. Her friend tried to console her: “Rosy, this is impacting who you are. This is impacting the way you think, the way you act.”

In some ways, Fish knows it always will. She cannot separate herself from that woman. From Indigenous women. She doesn’t want to. They are her. She is them. And all she wanted for them, for herself, was to feel safe.

So she kept running. Kept trying to raise awareness of violence against Native women. But despite her success on the track, Fish flew under the radar in terms of college recruiting. She had her best marks as a senior, when college scouts had largely already picked out their scholarship athletes.

Williams reached out to Iowa Central Community College, a nationally respected program. Within five minutes of receiving Williams’s email, Iowa Central coach Dee Brown responded. He was interested. And he’d soon learn she was the perfect fit: “She’s so motivated,” Brown says. “So focused, so hard working. She doesn’t want to let any one person, or any one team, outdo her. She’s eager and hungry to be the best she can be.”

Fish continued to race with the red handprint on her face as she helped the Tritons win the national title in 2019 and take second at the National Half Marathon Championships in 2020. She began to share her story with local Native kids and beyond, realizing that running gave her a platform. And, after watching Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel use her own platform, Fish felt she needed to do more to use hers as more and more Indigenous women turned up missing. And she hoped that if she shared the depths of her own struggles, it would make other Native girls and women feel less alone as they grappled with their own.

The first time she spoke to an assembly of schoolchildren, she was shaking. It was difficult, remembering how isolated, how worthless, she felt as a 14-year-old before attempting to take her own life.

She was vulnerable, cracking herself open for so many to see. But then she thought about how she wished someone back then had told her: “You are valuable. You deserve to take up space.” So she continued to speak.

“It’s comforting to know that she tells her struggles,” says Cedar McCloud, her sister, “so when people of similar identities go through hardships, it’s not as isolating.”

When Fish saw a little girl with long black braids in the audience that day, she felt something new: hope. Hope for the next generation.

“It was hypothesized that it would take eight generations in order to heal the trauma that was left from boarding schools,” Fish says. “I’m the fifth generation. And my great-grandchildren could live a life of no trauma from the boarding schools if I continue to work, and I survive, and I make it, and I try to break these cycles.”

That was part of the appeal of signing with the University of Washington, in a state with 29 federally recognized tribes. Her entire family was so proud. Less than 1 percent of all NCAA athletes are Indigenous. “I cried,” says her mom, Autumn, who herself is a graduate of UW Tacoma.

Fish’s great-grandfather, George Cross Jr., would have been proud too. He was a big Huskies fan. He’d often call UW “the best school in the world.”

Cross was the eldest Muckleshoot male tribal member when he died in March at 84 years old. He used to take Fish and McCloud’s grandmother, Rosalie Cross, whom Fish is named after, to the nearby White River.

When Fish was 6 years old, she would sit snuggled between them in their pickup truck. They’d eat sandwiches and watch the river glimmer as it caught the light. She heard stories of how sacred rivers are to her community, how it sustained them with food and water over generations.

For a moment, reflecting on these experiences, she feels peace. But then the anxiety returns. The women flood into her brain again. The women who still have not been accounted for.

Women like Alyssa McLemore, from the Aleut tribe, who has been missing from Kent, Washington. She’d be 33 years old now.

Women like Kaylee Mae Nelson-Jerry, who is Fish’s cousin. Nelson-Jerry grew up in Muckleshoot. She has been missing from Auburn since July 2019. She is 22 years old.

Lately, Fish and her mother have been talking more about the past and the future. What has been swept under the rug. Fish reminds her mother that she, too, deserves to heal.

As they recently reflected on difficult moments in Fish’s childhood, and discussed how scared Fish and her siblings felt at times, McCloud started to cry.

“Mom,” Fish said, “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

“No, no, it’s OK,” McCloud said. “I’d rather we talk about it.”

Fish leaned over and snuggled into her mom’s shoulder for a side hug. McCloud was surprised. Physical affection is still somewhat new for her. Hugs between the two of them have always been a little awkward, McCloud says, because she hadn’t grown up with physical affection, either. “It’s not because I don’t love you,” McCloud once told her daughter. “It’s that I don’t always know how to.”

On this afternoon, though, some thread between them had been untangled. They embraced a beat longer than either were used to. As they held each other, something in Fish shifted.

You belong here. You deserve to be here.