Time Is a Flat Ferris Wheel: The Enduring Legacy of ‘RollerCoaster Tycoon’

In 1999, ‘RollerCoaster Tycoon’ hit shelves and turned millions of kids into virtual theme park designers. Twenty years later, it not only evokes nostalgia among those who played—it holds up as a symbol of creativity and the power of online community to change lives for the better.At first, Chris Sawyer hated roller coasters. As a child growing up in Scotland, he rode them with a mix of curiosity and dread, screaming to get off every time he barreled through another stomach-flipping plunge. This is a common trait among people who ultimately become obsessed with theme parks. They learn not only to conquer their fear, but to take control of the machines that once terrified them.

Sawyer has long been fascinated by coasters and the precisely constructed worlds in which they reside. For kids, theme parks are proof that life can be as thrilling as their wildest fantasies. For adults, they’re a fleeting reminder of that carefree mind-set. As Sawyer got older, he gained an increased appreciation of roller coasters, and came to enjoy them more as he understood their complexities. Eventually he decided to build his own fantasy world—not with wood or with steel, but with computer code.

RollerCoaster Tycoon, released 20 years ago this past Sunday, became the greatest theme park of all for a generation of kids who found it easier to visit the Scholastic Book Fair than Walt Disney World. Like any truly great park, the game seemed to exist outside the normal boundaries of time. Its merry-go-rounds and swinging ships evoked the humble county fairs that had dotted the American landscape for decades, while its most epic attractions were based on modern designs by the elite roller-coaster manufacturers of Europe. The colorful 2D sprites were a step behind the graphically advanced titles of the era, but they’ve aged better than almost anything else released in 1999. RCT was more tethered to the real world than most games—managing marketing budgets and cleaning up vomit were billed as entertainment—but that only helped it create a more orderly, governable version of reality where it was easy to lose yourself for hours.

Despite its nostalgic leanings, RCT also portended the future. It was many players’ introduction to the simulation genre, which now touches games as varied as Red Dead Redemption 2 and the interior decorating mobile app Design Home. For others it was a gateway to an archipelago of online communities filled with theme park fanatics, physicists moonlighting as roller-coaster designers, and artists excited to work with an interactive canvas. For a few, it was a creative spark that would change their lives.

Because RollerCoaster Tycoon can be played in an infinite number of ways, it impacted each person who picked it up differently. But for many of the game’s most devoted fans, the internet helped to craft a shared experience: venturing online to download new rides, appraise others’ parks, and even develop gameplay mechanics Sawyer himself hadn’t implemented. RCT was more than just a virtual sandbox—it was a communal toy box that anyone with an internet connection could rummage through for inspiration. “It’s something to do with the free-form nature of the game,” Sawyer says in an email. “Players become very attached to their own parks and their creations, so they feel like it’s their game rather than my game.”

Sawyer did not set out to change anyone’s life. He only wanted to make a follow-up to his first hit game, Transport Tycoon. The 1994 title tasked players with building a logistics company to transport goods by land, sea, and air. After its modest success, Sawyer began work on a sequel that would feature multilevel bridges, curved roads, and other complex structures. He quickly realized these designs could be applied to roller coasters just as easily as transit systems.

As he was rethinking his sequel, Sawyer was also indulging his theme park obsession. He bought books about the history of roller coasters—White Knuckle Ride, The Roller Coaster Lover’s Companion, The Incredible Scream Machine—and began imagining how the contraptions could be reconstructed in video-game form. He joined the Roller Coaster of Club of Great Britain, through which he traveled to parks around the world. One trip took him on a tour of 14 theme parks in the American Midwest, stretching from Michigan to Ohio. He took notes on three factors of the thrill rides that would be baked into RollerCoaster Tycoon’s core mechanics: excitement, intensity, and nausea.

It all seemed like quite a big risk at the time. Transport Tycoon 2 was seen as a guaranteed hit whereas a game focused on roller coasters was seen as a niche product.Chris Sawyer, RollerCoaster Tycoon creator

By 1997 he had fully committed to the theme park idea. He spent about two years coding the entire project himself in x86 assembly, an early programming language that was used to create many video games in the 1980s. X86 assembly is what’s known as a low-level language, meaning that it’s not far removed from the basic binary inputs that guide the actions of computer processors. Writing a complex, quasi-3D game like RollerCoaster Tycoon in that language was a Herculean effort, especially for a title that lacked an established market. “It all seemed like quite a big risk at the time,” Sawyer says. “Transport Tycoon 2 was seen as a guaranteed hit whereas a game focused on roller coasters was seen as a niche product.”

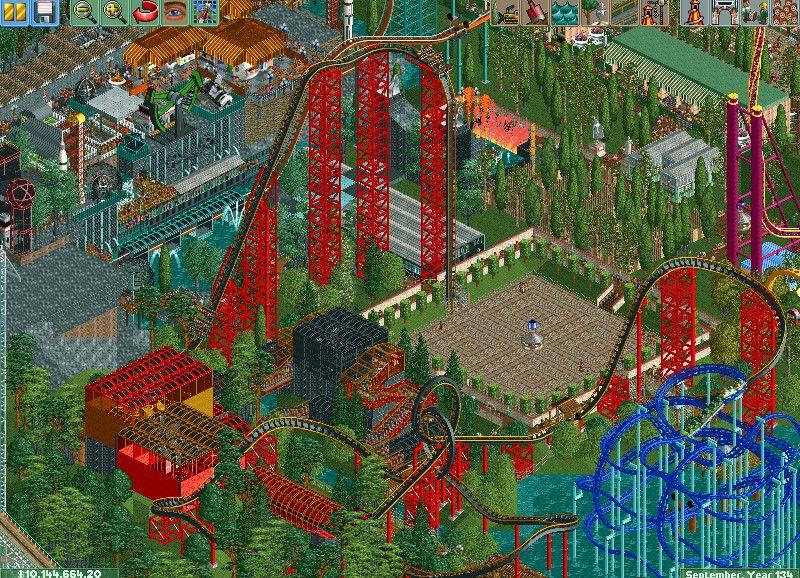

RollerCoaster Tycoon, though, was an immediate success. It became the bestselling PC title of 1999, and by 2002 had sold 6 million copies. The game included the financial management aspects of SimCity, the true godfather of the simulation genre, and forecasted the do-it-yourself design sandboxes found in modern titles such as Minecraft. RCT managed to be at once simple and exceedingly complex, turning experimentation into its own reward. While it featured 21 preset business scenarios that challenged players to improve parks under development, it was the wide variety of prefabbed attractions, the free-form terrain editor, and the physics system undergirding the custom roller-coaster builder that opened up limitless possibilities for creativity.

This creativity forged connections, as the game blossomed into an internet phenomenon from nearly the moment it was released. “I remember right at the beginning, when the original game was launched in 1999, being surprised at how quickly players were becoming passionate about the game and sharing their experiences and wish lists online,” Sawyer said. Twenty years later, fans still talk about their experiences playing RCT and later installments RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 (which Sawyer also designed) and RollerCoaster Tycoon 3 (on which Sawyer served as a consultant) with a certain amount of reverence. These titles are not merely relics of tech nostalgia. They’re the foundation of communities in which users have plugged away at their parks for decades, shaping online worlds as complex as the digital ones that can be built with Sawyer’s tool set.

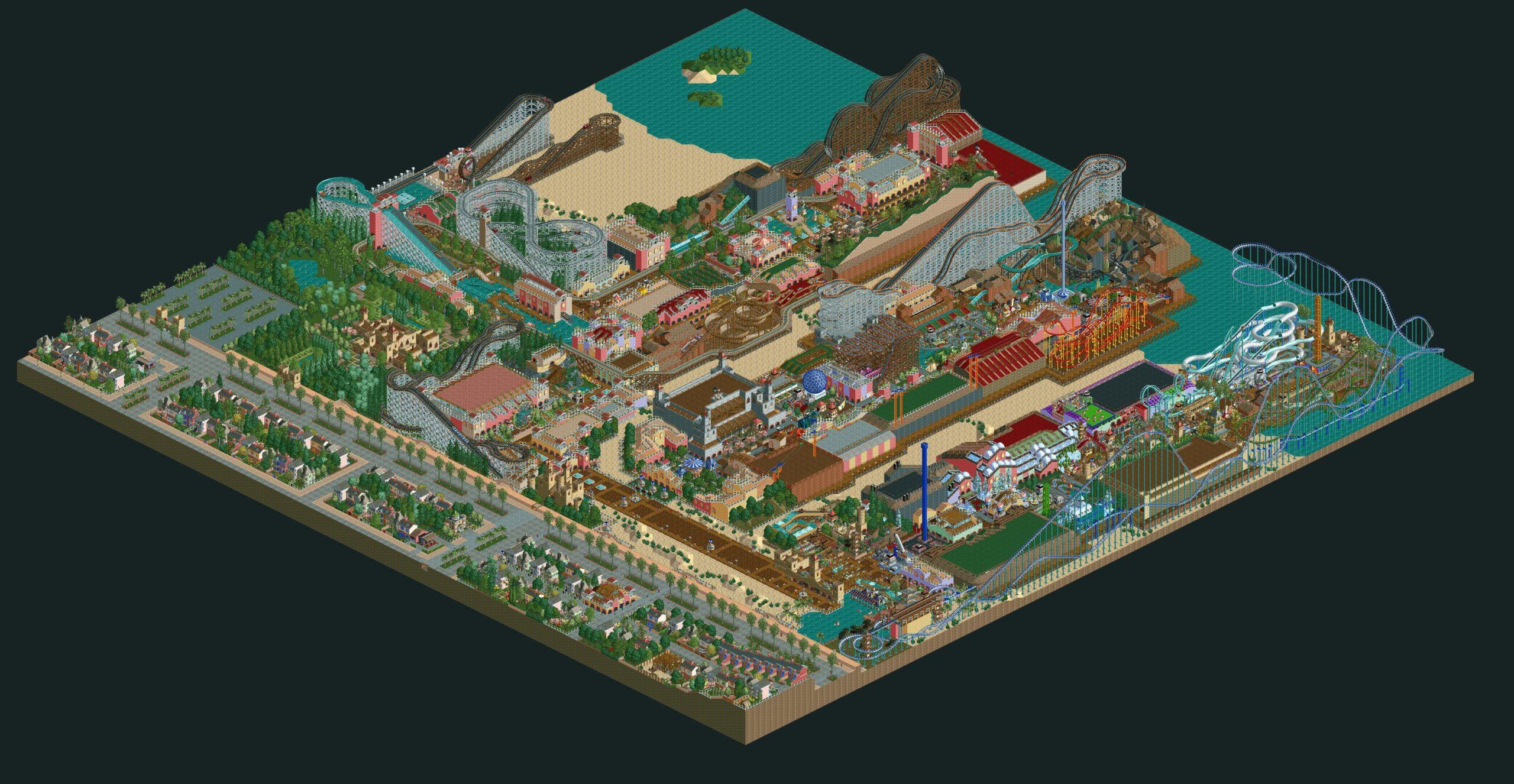

Alexander Krikes’s Bell Gardens on ‘RollerCoaster Tycoon 3’

RollerCoaster Tycoon came along just as millions of people were gaining home internet access for the first time. It arrived as fan sites and message boards dedicated to all sorts of niche hobbies—like obsessing over a specific video game or traveling the world to visit amusement parks—were turning the web into a highly personalized experience. And RCT was itself a highly personalized game. Some players specialized in designing gravity-defying coasters. Others laid out elaborate parks. A few used the tools to create worlds that were not even theme parks, like cityscapes or alien warships. Though the game didn’t include a multiplayer mode, the fact that it was a PC franchise meant trading coaster designs and park layouts was as natural as exchanging emails.

“Finding that there were all these other people who loved this game as much as I did was fantastic,” Bob Morrow, a 62-year-old retired video store manager who lives in Brazil, said in a forum message. “I discovered all sorts of tricks that even I could use to build a better park. Sharing screenshots was just like taking an advanced course in school ... and it was free!”

For an online community, they’re very nontoxic. They’re very supportive, just because that’s what you need to get better at the game.Silvain Hamar de la Brethonière, on the RCT community

Morrow was a staff member on several of the RollerCoaster Tycoon fan sites that sprouted up in the early 2000s. At one point he was fielding invites to join new ones nearly every week. Many of these, such as RCT Station and the official Atari forums, are either no longer active or have disappeared into the digital ether. Morrow continues to frequent the message board Shyguy’s World, one of the few sites of the era that has survived the internet’s shift to social media. “For me it has a lot to do with age and experience,” he said. “I prefer the focus that message boards give a topic, [whereas] I find social media can bounce all over the place.”

Another longtime hub is New Element Designs, which has gained a reputation as the ivory tower of RCT fanatics since it launched in 2002. Players post exceedingly elaborate maps that are reviewed by other elite park planners. (A recent take on a snow-themed park called Fossegrimen: “A lovely little design. We don’t get many winter themes, so this was a pleasant surprise … the archy is detailed and vibey but maybe a bit too colorful for me.”) Those who score high enough marks are deemed NE, Elite, or Legendary Parkmakers. Often the maps are based on real theme parks: a recreation of Cedar Point’s famed Raptor coaster in Ohio, an adaptation of Knott’s Berry Farm in California, a theoretical Six Flags Santa Fe based on the design principles of the company’s actual attractions. “There’s definitely recreations of almost every major park in America on there somewhere,” says Dave Callen, an offshore geophysicist in the U.K. and longtime New Element member.

On New Element and sites like the RollerCoaster Tycoon subreddit, almost all modern park design is happening in RollerCoaster Tycoon 2. That’s thanks largely to the efforts of hundreds of fans who have contributed to OpenRCT2, an open-source version of the game that is more playable on modern machines and includes new features like multiplayer. Though the project began in 2014 as a one-man endeavor by a 21-year-old software developer named Ted John, it’s been improved by more than 250 contributors in the years since it launched.

These various communities now tend to overlap. Some of the same people judging parks on New Element offer tips to newcomers on the RCT subreddit. Fans often hop between multiple Discord chat rooms to discuss the game and work on collaborative projects. Many of the longtime series fans I talked to had frequented Shyguy’s World. People tend to know of and respect one another’s creations. While many online communities have devolved into dens of verbal abuse and trolling over the years, the RCT groups remain largely positive. “For an online community, they’re very nontoxic,” says Silvain Hamar de la Brethonière, a Dutch fan who goes by Silvarret on his popular YouTube account. “They’re very supportive, just because that’s what you need to get better at the game.”

It still kind of is my obsession. I got to live my dream on a smaller scale.Derek Rochelle

What unites these fans is an intense focus on perfecting their digital creations. Parks can take months or years to build. For most designers, there’s no recognition beyond a Parkmaker badge on the New Element website or an upvote on Reddit. While the past decade has seen corporations and individuals try to monetize seemingly everything online, from Facebook mining its users’ data to Instagram influencers turning daily banality into endorsement deals, most RCT fans continue to play by the rules of the old internet. They create parks because it’s fun, because they’ve found a community of friends who also enjoy it, and because it fulfills a fantasy that’s almost impossible to achieve in the real world.

“I always drew pictures of amusement parks, because I wanted to design them when I grew up,” says Derek Rochelle, a 49-year-old high school art teacher who used to be an engineer at a NASA contractor and has been a regular presence on Shyguy’s World for more than a decade. Rochelle had visions of working at Disney when he was a kid. Playing RCT and its 2016 spiritual successor, Planet Coaster, have allowed him to turn a childhood passion into an adult hobby. “It still kind of is my obsession,” he says. “I got to live my dream on a smaller scale.”

Alexander Krikes, a recent graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design, poured thousands of hours into RollerCoaster Tycoon games as a kid. He built hundreds of parks in the franchise’s first three installments, scribbling notes about his ideas in class so that he’d remember what he wanted to build when he got home. He gained an encyclopedic knowledge of the manufacturing styles of real roller-coaster manufacturers—Bollinger & Mabillard, Intamin, Mack Rides—and then applied them to his custom-designed theme parks. A favorite of his, called Bell Gardens in RollerCoaster Tycoon 3, took a year and a half to make.

Krikes is now an operations associate at Legoland California Resort. He hopes to one day become a master planner or creative director for a major theme park. He cites the lessons that he learned playing RCT and sharing his work on Shyguy’s World as the motivation to pursue his profession. “Sticking with a project for that amount of time, even as a hobby, definitely gives you a bit of patience. You could consider people in the forum similar to all the managers that are sort of hovering over you, watching the work you’re doing on a project,” he says. “It definitely influenced the way that I work on projects today.”

Among the millions of people who picked up the RollerCoaster Tycoon games over the past 20 years, a select few now design rides that millions more visit in real-world theme parks. Young engineers in the amusement park industry say that RCT is a common reference point for people in their generation. Eric Kaminsky, a 28-year-old engineer for Universal, is working on an upcoming $6.5 billion theme park in China. As a member of the Beijing park’s creative team, he is helping to design one of the attractions for the facility. “RollerCoaster Tycoon has totally influenced how I think about which way we should be turning or going up or down and how fast we should be taking these hills,” he says.

I graduated from just designing a ride to being concerned about what the layout of the whole park looked like, what the diverse portfolio of attractions looked like. That’s what RollerCoaster Tycoon did.Dionté Henderson

Because the ways people play the game are so varied, RCT imparted many different lessons upon future park designers. Dionté Henderson first played the original RollerCoaster Tycoon at a friend’s house after school in the sixth grade, designing outlandish rides as his buddy managed the queues. Later, he became even more immersed in the franchise when he finally had his own computer to play RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 on. He spent three years working on a single park he called Great Falls, aiming for realism over absurdity. He redesigned cartoony food stalls to look more realistic. He fretted over foot traffic patterns and walkway congestion. He designed coasters with banked turns that could pass muster in a real theme park. “I graduated from just designing a ride to being concerned about what the layout of the whole park looked like, what the diverse portfolio of attractions looked like,” he says. “That’s what RollerCoaster Tycoon did.”

All of these hard-core RCT fans spent at least some of their childhoods on message boards and fan sites, trading tips with other enthusiasts and learning techniques from more advanced players. Henderson is now an engineer at Universal Creative, and was deeply involved in the design and implementation of a recently opened water park called Volcano Bay at Universal Orlando Resort. When I ask him what makes a good theme park ride, he demurs. “You have to explore your context,” he says. “One lone thing doesn’t make a great attraction. You can’t just say, ‘Oh, I’m gonna go for a thrill ride,’ because what if that’s not what the park really needed? What if the park needed something was more geared toward the family? You really have to understand that.”

This seems like an evasive answer at first, but it gets at the very essence of RollerCoaster Tycoon’s legacy. The game is technically a business sim loaded with preset goals for making money or setting attendance records, but it’s not about winning. It’s about building an ecosystem in which each attraction thrives off the strength of its surrounding environment. That’s the world we all want to live in, both online and off.

A video game created a fantasy so vivid that young engineers now acknowledge it as a core influence on the dream worlds they’re building for the rest of us. And though this franchise just turned 20 years old, it’s still attracting new diehards. The hard-core fans who continue to populate RCT forums, subreddits, and Discords say that the recently released mobile versions of the classic games have brought a surge of young new players into their communities. It seems gamers will always be curious to explore a universe that stretches from their own digital parks to the communal gathering places on the internet and out into the physical playgrounds where people young and old venture to lose themselves.

The circularity of the franchise’s influence amuses Henderson. “My life is now a real-life RollerCoaster Tycoon,” he says. “This very much became an escape, and then it became my reality.”