The documents that prove that Josephine Bolling McCall’s father was lynched are displayed in her living room like courtroom exhibits. There’s the front-page 1947 Montgomery Advertiser article reporting that Elmore Bolling, a 39-year-old Negro of “excellent reputation,” was shot seven times outside his own store—six times in the front with a pistol, once in the back with a shotgun. There’s Bolling’s death certificate, confirming the veracity of his passing, if not the circumstances. There’s a Chicago Defender article asserting that Bolling was targeted because he was “too successful to be a Negro.” And a letter from Montgomery NAACP chapter member William G. Porter to NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund attorney Thurgood Marshall noting that the killing of a black man via gunshot by what he speculated to be a pair of white assailants represented “a new type of lynching.”

Josephine was 5 years old when the killing took place, leaving her and her six older siblings fatherless in Lowndes County, Alabama. “My memory is of my father deceased in a ditch with his eyes open,” she says.

It wasn’t until decades later that she began piecing together the specific details of Elmore Bolling’s death. She interviewed 51 people, trawled through newspaper clippings, and traced her own family history back to antebellum Virginia. She talked to family members who had never spoken at length about the murder and was rebuffed by other people who still feared reprisal. She wrote a 349-page book bluntly titled The Penalty for Success: My Father Was Lynched in Lowndes County, Alabama. She spent 10 years of her life building an argument about America’s history of racialized violence that still reads as radical: This happened.

On April 23, Bolling McCall and her husband, Charlie, visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a new memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, dedicated to victims of lynching, slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and mass incarceration. The project was developed by the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery-based nonprofit that provides legal representation to prisoners, many on death row. Financed by private dollars fundraised by EJI and built on a hill that overlooks the local skyline, the memorial at once feels like a natural addition to a deeply historic city and a wildly ambitious outlier. Montgomery is a place torn between two opposing legacies—the city seal features the slogan “Cradle of the Confederacy” encircled by the phrase “Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement.” But the new memorial, as well as an accompanying downtown museum, attempts to fill in the gaps between these famous racial paroxysms, weaving a narrative so vast and devastating that most Americans choose to ignore it.

The centerpiece of this effort is a sprawling wood-and-metal open-air structure featuring 800 6-foot columns, each one representing a county where a lynching took place in the United States between 1877 and 1950. EJI took on a mass-scale version of Bolling McCall’s quest for truth, crisscrossing the South over the course of six years to compile a comprehensive list of these public murders. The organization issued a report in 2015 documenting 3,959 lynchings across the region. Additional research in more states has increased the figure to about 4,400.

Each of these victims’ names is etched onto one of the 800 columns, which surround the viewer at eye level upon entering the memorial. None of the columns are telling exactly the same story—made of corten steel, an alloy that changes hue when exposed to air, they’ve each morphed to a different shade of brown over time. As you wind your way through the memorial, the floor slopes downward and the eerie symbolism of a cluster of human-sized columns suspended by metal poles becomes more apparent. Eventually, the columns stretch too far in the air to clearly read the names, so the viewer can only assess them in aggregate. The terror of lynching becomes mass spectacle, as it was when it was happening across the South less than a century ago. The structure evokes the haunting photo of a mutilated black body hanging over a crowd of white onlookers, but turned upside down. “The whole point of lynching was to raise up this violence,” EJI executive director Bryan Stevenson says. “And you can’t appreciate the scale of that terror unless you’re walking with these monuments [hanging] over you. … You feel shadowed. You feel haunted. And I think we should feel haunted by this.”

Elmore Bolling’s name is here, the last in a list of 16 lynching victims from Lowndes County. His story, and his daughter’s work uncovering it, is part of the mounting ledger of evidence of a great crime committed by individuals, by communities, and by American society. “What [the Equal Justice Initiative has] done now is put names and faces on lynched people,” Bolling McCall says. “The thing that’s so important to me is that I can put a face on my dad and talk about him. There are so many victims who were not able to do that.”

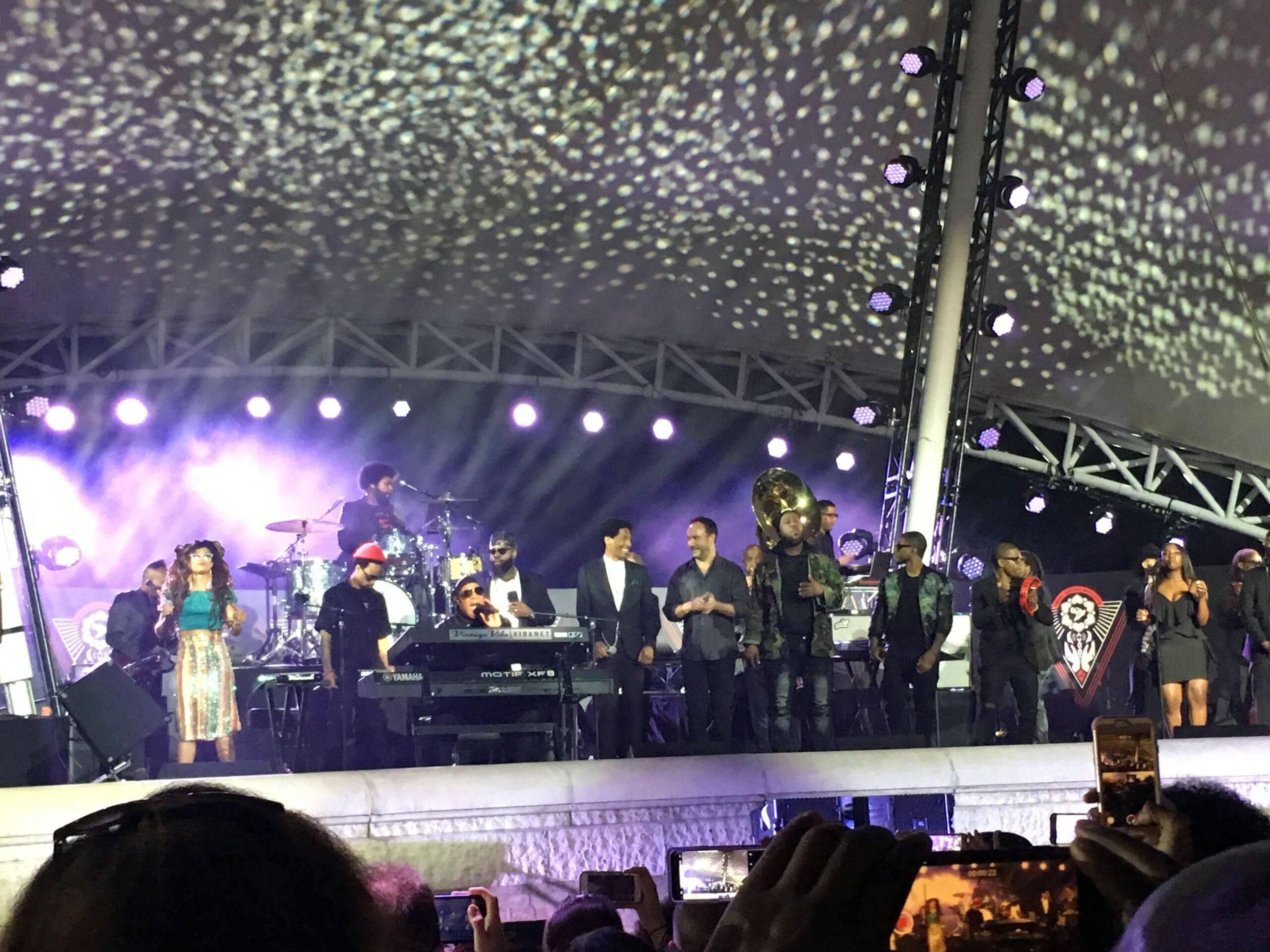

It’s strange to witness your conservative hometown hosting, in the words of Stevenson, “amazing conversations from the most woke people in America.” The debut of the lynching memorial was accompanied by a two-day justice summit filled with panels by academics and activists, an opening ceremony anchored by John Lewis and Patti LaBelle, and a celebratory concert at the local amphitheater showcasing A-list rap, R&B, and gospel stars (also: Dave Matthews). The capital of the state that gave Donald Trump one of his largest margins of victory in the 2016 election is now home to a museum and memorial that film director Ava DuVernay said were “drenched in blackness.”

The pageantry brought to mind 1965’s Selma-to-Montgomery march. Civil rights activists twice failed to complete the trek, most famously on Bloody Sunday, when state and local police viciously attacked 600 marchers on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. But Bloody Sunday became a cultural flash point illustrating the urgent necessity of the civil rights movement. By the time Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, and other leaders made a third, successful sojourn, they were accompanied by thousands of marchers and a cadre of celebrities, including James Baldwin, Joan Baez, and Tony Bennett. Nina Simone performed “Mississippi Goddam” at a star-studded concert on the outskirts of Montgomery to commemorate the occasion.

For people with ties to Montgomery, the connection between that moment and this one resonates deeply. “At 5 years old, my father was one of those kids waving to the marchers as they went by,” said DuVernay, who has multiple siblings who live in the city. “This feels like home to me, this place.”

“It was a city shaped by slavery. We had one of the highest lynching rates in the region. Then of course the centrality of the civil rights era. And now Alabama has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country. … I don’t think there’s a community that can claim more appropriateness for telling this history than this one.” —Bryan Stevenson, Equal Justice Initiative president

Montgomery’s strengthening status as the epicenter of the United States’ racial reckoning makes sense when you peel back the layers of the city’s history. That it was the first capital of the Confederacy and the home of the pivotal black bus boycott is well known. But fewer people are aware that Montgomery was a thriving slave market because of its proximity to the Alabama River, or that the city’s population was two-thirds enslaved people in 1860, or that the global investment bank Lehman Brothers began in Montgomery by profiting from the slave trade. “It was a city shaped by slavery,” Stevenson says. “We had one of the highest lynching rates in the region. Then of course the centrality of the civil rights era. And now Alabama has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country. … I don’t think there’s a community that can claim more appropriateness for telling this history than this one.”

Stevenson said this on Confederate Memorial Day, a state holiday that included a ceremony for Confederate soldiers on the grounds of the capitol. Just days before the lynching memorial opened, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey released a campaign ad defending the state’s 2017 law that prevents the quick removal of Confederate statues. The Equal Justice Initiative efforts are not only an attempt to uncover truth—they’re a counterargument to a whitewashed Southern narrative that remains resonant.

“When lynchings happened, there was a silence that fell and there was a compact [among whites] that you didn’t talk about it,” Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal and Educational Defense Fund, said during one panel. “[They were] gaslighting the black community into believing something that happened in their community didn’t happen. … It allowed white people to own truth.”

On Friday morning, the second day the lynching memorial was open to the public, visitors snapped photos of dozens of placards below the hanging columns explaining why black people were lynched. James Neely complained when a white store owner refused to serve him. David Hunter left the farm where he worked without permission. Warren Powell stood accused of “frightening” a white girl. Later I watched young visitors huddle around these images on their phones, sharing the revelations they’d unearthed with anyone nearby.

Out in a plaza beyond the suspended monuments, a second set of identical columns is organized in alphabetical order by state. The idea is that each county where a lynching occurred will eventually claim its column and put it on display as a local acknowledgment of a dark past. For now, though, the columns serve as a way for visitors to bring digital evidence back to their communities about what they learned in Montgomery.

We live our day-to-day lives, and a lot of us don’t focus on our history.Shantayia Williams

“The pictures I focused on were counties that I’ve lived in or counties that I have friends in … to see how many names and how much blood is in the soil of a city that I love,” says Shantayia Williams, a 33-year-old resident of Atlanta. “We live our day-to-day lives, and a lot of us don’t focus on our history.”

“Just being able to share that with them and take that home to them,” Williams says, “that’s what was significant.”

I met a 36-year-old pastor named Bam Stanton who was scribbling drawings of flowers and handing them out to people as they passed. He’d flown down from Chicago with a couple of friends after learning about the memorial two months ago. As he stood in a grassy square in the center of the names of the lynched, he recited Langston Hughes’s poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

“This is a holy place,” Stanton said. “It’s holier than any sanctuary I’ve ever been in. This is just a whole ’nother level of embracing this pain.”

On Friday night, EJI hosted a concert to cap the week’s festivities. It was a musical bounty beyond my small-town comprehension. Common rapped “Glory” with Tasha Cobbs and the Alabama State University choir. Kirk Franklin led a gospel rendition of “Lean on Me” while wearing a Black Panther jacket, then used his pulpit to encourage everyone in the audience to hug three strangers. Usher, backed by the Roots, improbably turned “OMG” into a church revival (Questlove wore a shirt that said “Kanye Doesn’t Care About Black People” in the Life of Pablo font).

Then Stevie Wonder came out, a surprise guest introduced personally by Stevenson. After a crew member ushered him onto the stage, he stood over his piano alone for at least a minute. The audience cheered to break the tension. “I come to you tonight with a deep pain in my heart, with a great love in my soul for all of you,” he said finally. “I have and I will for the rest of my life give to God by giving to you the gift that he’s given to me. My song, my love, my hope that we will come together as a united people not only in this country, but in the world, before it’s too late.”

He opened with “Love’s in Need of Love Today,” then entered into a fire-spewing rendition of “Higher Ground” with Questlove bathed in the red glow of the stage lights behind him. As the applause subsided, he stood up and walked from his piano over to a nearby harpejji. The tension was back. He sat and pulled the microphone toward his lips. “This song was not planned,” he said.

He started playing a melody I didn’t recognize at first, though it had a familiar ache. On the two jumbo monitors that flanked the stage, the artist’s weathered brown fingers plucked pain from the strings of his tiny instrument. Stevie started singing and for once, no one had their phone out. It was “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.”

In the lynching memorial, there’s a spot where you can gaze upon the final corridor. The cascade of brown bodies, reborn in oxidized steel, seem to stretch endlessly toward some higher plane. To their right, the burst of sunlight casts their casings in an ethereal glow. To their left, a black wall glistens under the current of a waterfall. “Thousands of African Americans are unknown victims of racial terror lynchings, whose deaths cannot be documented, many whose names will never be known,” the wall reads. “They are all honored here.”

Stevie conjured this image in my mind as he turned those names hanging in Montgomery into something more awful, more beautiful, more immediate than I had allowed myself to realize for many years. He sang, for a long time, about the everlasting hope of salvation. “I want you to think and feel the pain,” he said as his hands first settled over the harpejji strings. “We have to remember that pain.”