The past is a foreign country. It will take a long time to explain Eli Manning to those who weren’t there. Manning beat a juggernaut Patriots team in the Super Bowl twice. He was a first overall pick. He has made $252 million in his career, more than any other NFL player in history, and $4 million more than his brother, Peyton. He was a television darling regularly placed in front of prime-time audiences. If this is the end for Manning, he has had a good football life. He has also, it needs to be pointed out, looked overwhelmed for large portions of games. He has a 116-116 career record. He has never made an All-Pro team. His style of play looked outdated for almost his entire career. Two years ago, the Giants benched him for Geno Smith, a move that got the coach fired and somehow resulted in Manning accumulating more juice. His production has been, at best, average for significant stretches of his career. His ability to endure the past 15 years in New York is so remarkable that Robert Caro should be rushing to East Rutherford to write about Manning’s soft power. In 20 years, when a young person asks you about Manning, the best way to explain him is to say that he beat Tom Brady twice. It will be easily understood because at that point Brady will have just won another Super Bowl.

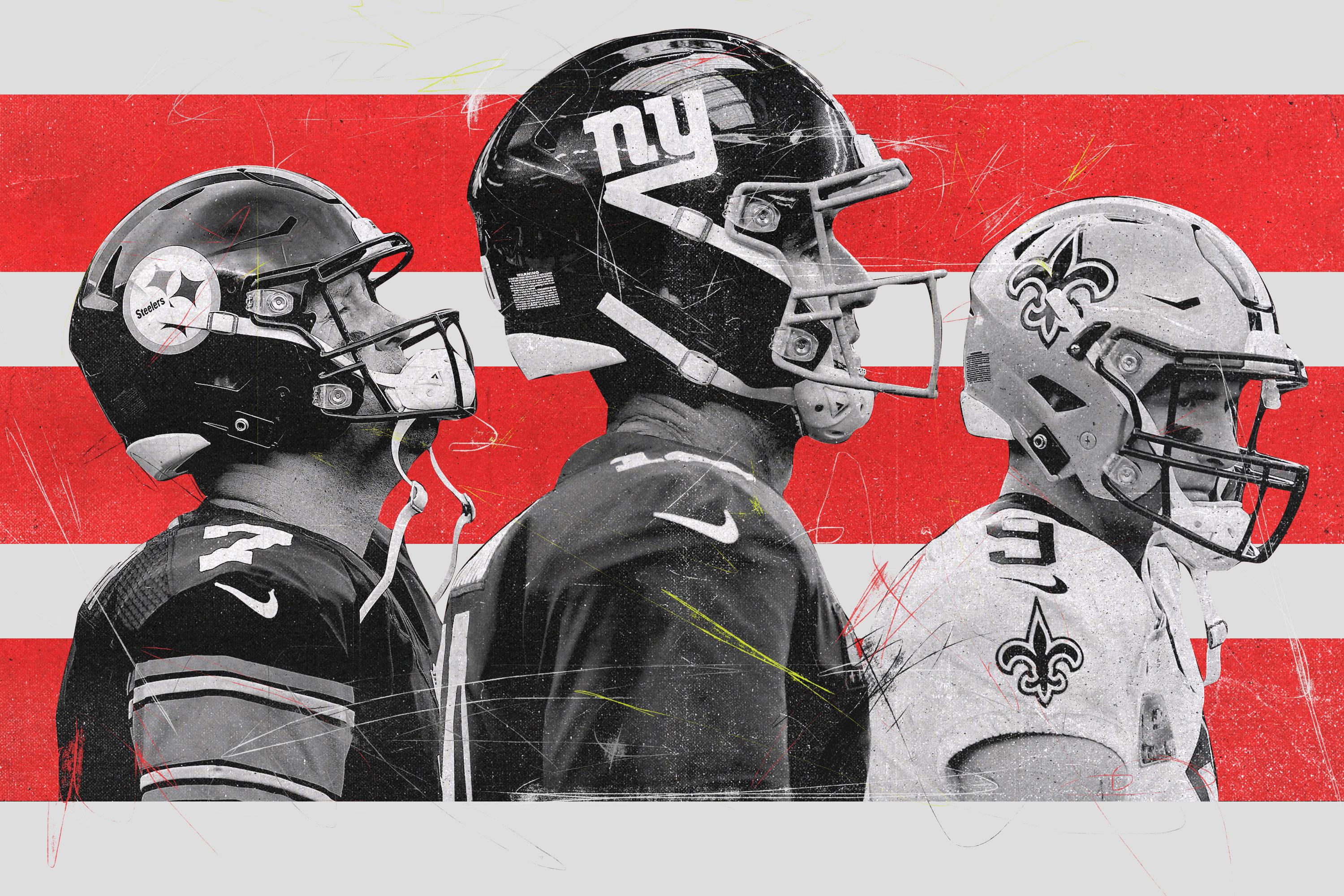

The Giants benched Manning on Tuesday for rookie Daniel Jones. It is hard to say anything is the end for Manning, but this feels like it. Pair this with Ben Roethlisberger’s season-ending elbow injury, and it feels like the famed 2004 quarterback draft class, which includes Manning, Roethlisberger, and Philip Rivers, is nearing the end of its reign. Drew Brees, drafted three years earlier, is out six weeks with a hand injury. Manning, Roethlisberger, and Brees are three of the top five earners in the history of the sport—a testament to their longevity, success, and fame—and none will play this weekend. This feels like the end of something.

Now is not a time for obituaries: We’ve seen Manning return from a benching, Roethlisberger could be ready to roll by this time next year, and Brees might lead the Saints roaring back when he returns at midseason. But unlike any other time in the NFL, a generation of younger quarterbacks is pushing an older generation out of relevance. When you watch Patrick Mahomes, Baker Mayfield, and Lamar Jackson, especially in comparison with Manning and Roethlisberger, it is hard not to see what has happened to the sport.

I’ve dubbed this the era of the Forever Quarterback—each week, a new record is set by an older, elite quarterback. The problem, of course, is that when you have a group of signal-callers playing at unprecedented ages, you never know when it’s going to end. There is no group of quarterbacks like the one drafted in the early 2000s, and thus there is no guide for how teams should deal with them as they get older. The Steelers just signed Roethlisberger to a new deal that will pay him $45 million in cash this year, which is more than anyone in U.S. sports and $5 million more than Warriors guard Stephen Curry will make next season.

The Steelers have moved on in the short term by trading a first-round pick for Dolphins safety Minkah Fitzpatrick, signaling at least some faith in backup Mason Rudolph to salvage this season. The Saints made Teddy Bridgewater the highest-paid backup in the league in March, partly in case Brees got hurt, but also so that Bridgewater could potentially be Brees’s heir apparent—a sound plan, it appears. The Giants planned ahead by taking Jones in the first round of this year’s draft, but the team stressed that it wanted to follow the “Kansas City” model in which Mahomes spent his rookie season playing behind Alex Smith before taking over the starting job in his second season. Giants owner John Mara said he hoped Jones “never sees the field” because it would mean Manning was having a good year. Reader, Manning did not have a good year. And so this is how it ends, not with a bang, but with Daniel Jones.

The Forever Quarterbacks have been a historically productive group. The enduring success of this generation made sense: They were a talented crop who came in several years before the league’s collective bargaining agreement in 2011 changed practice rules by limiting teams to 14 padded practices during the regular season and eliminating two-a-days in training camp. These changes benefited them on two fronts: First, the quarterbacks who entered the league after the CBA received far fewer valuable NFL practice hours. Second, the new rules helped preserve the bodies of the quarterbacks already in the league. They spent seven or so years getting as many reps as they could and then, once they had it down, the league changed the rules so that they wouldn’t have to go through grueling practices anymore. The ladder was pulled up as soon as they perfected their craft.

Other rule changes also favored players like Manning, Roethlisberger, and Brees, including stricter protections for quarterbacks and rules that limited defenses. Roethlisberger led the NFL with 5,129 passing yards last year, which is 500 more than any team in the league in 2004, the year he was drafted. Football in 2019 is a different sport than the one these quarterbacks played when they entered the league because, in the midst of all of these rule changes, the sport changed again. The league shifted toward more spread concepts, stolen from college. There was a very real scheme war in the NFL—old, headstrong coaches resisting change vs. younger, innovative coaches—and young quarterbacks like Mahomes and Mayfield helped win that war for the youth movement. In a strange way, the tension between old-school tactics and new ideas helped the older generation of quarterbacks. NFL coaches essentially failed many years’ worth of quarterbacks by not figuring out how to build on the schemes they learned in college. Had they been successful, perhaps the Forever Generation would have aged out more quickly. This is not to say older quarterbacks cannot be productive in this era—Brees and Brady, among many others, have been awesome—it’s just to say they did not grow up playing in the aggressively modern schemes you see in the NFL today, and despite having innovative coaches, they are no longer on the cutting edge of the sport. Manning and Roethlisberger changed along with the sport—anyone who existed in the passing boom era had to—but the sport changed on them one too many times for them to keep up.

I’ve talked to people in the Eagles organization about the decision to trade up in the 2016 draft to select Carson Wentz and how, internally, they looked at these Forever Quarterbacks as a model: Yes, it’s a lot to trade up for a franchise quarterback, but once you have one, you can enjoy him for well over a decade without having to worry about it again. A franchise quarterback is a long-term problem-solver. Despite some of the lows teams have experienced with their franchise quarterbacks, they have had more highs than, say, a team like the Jets, who have spent 15 years in the quarterback wilderness.

There will still be old quarterbacks. Rivers is still going. Brady will play forever. Brees will be back. Aaron Rodgers looks like he’s about to lead another contender. But Manning and Roethlisberger might be on their way out. Fifteen years is a long time to thrive in the sport. It makes you think about who will be around 15 years from now: Mahomes, surely, Mayfield and Jackson, presumably. And Tom Brady.