The Starting 11: What Super Bowl LIII Can Teach Us About the Future of Defense

There was no one cheat code that Bill Belichick and Wade Phillips used to slow down the Rams and Patriots offenses Sunday. But both staffs found success by valuing similar principles—and provided a preview of how teams could look to stop the NFL’s next wave of high-flying offenses.

Welcome to the Starting 11. This NFL season, we’ll be collecting the biggest story lines, highlighting the standout players, and featuring the most jaw-dropping feats of the week. Let’s dive in.

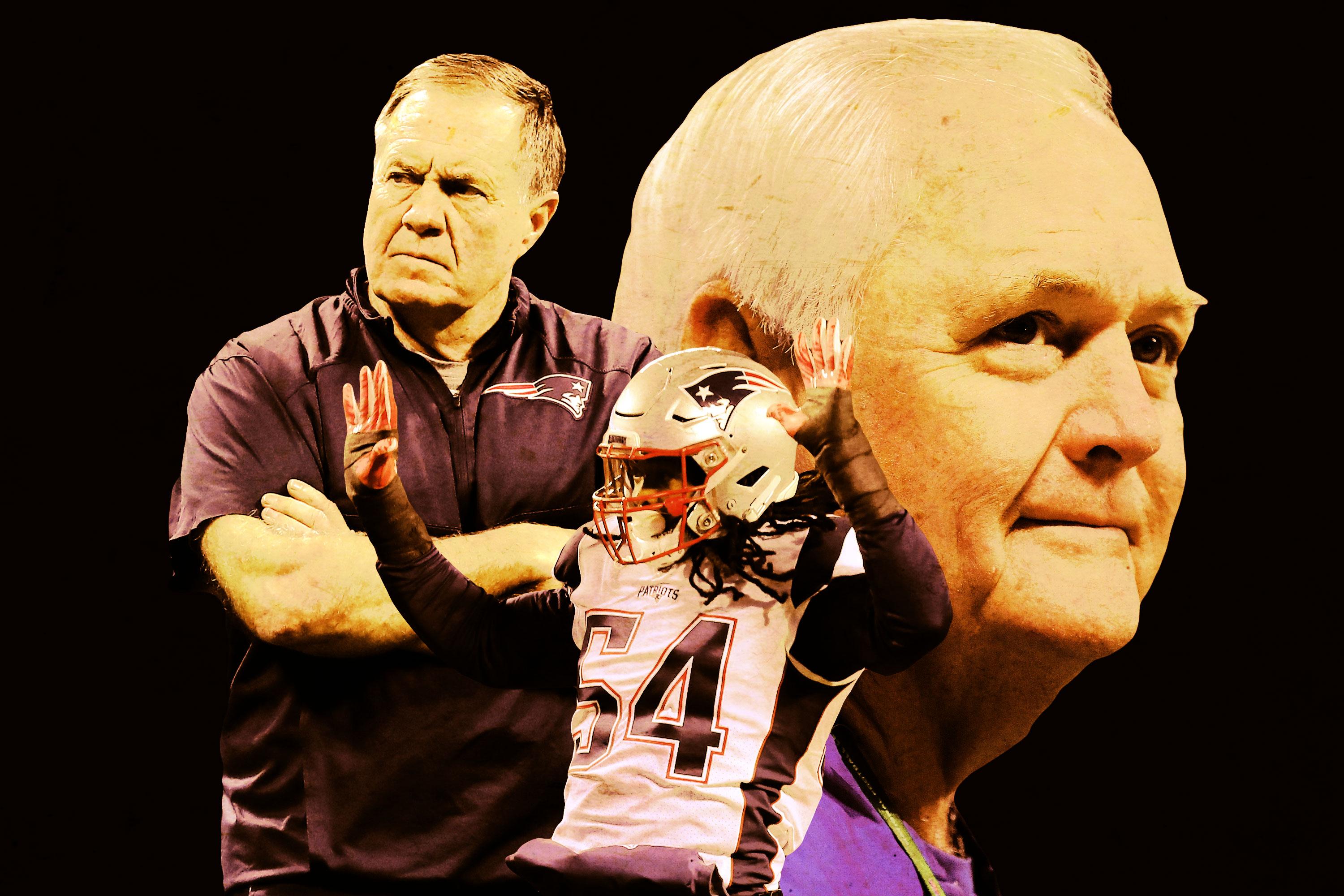

1. The power of youth was a common theme in the NFL this season. On Sunday, Jared Goff, 24, became the fourth-youngest quarterback to start a Super Bowl. Sean McVay, 33, was the youngest coach in the game’s history. The previous night, Patrick Mahomes II, 23, was named MVP, making him the second-youngest player to win. All that was new ruled the league in 2018, which made it even more fascinating to watch two guys eligible for Medicare pants these tykes on the sport’s biggest stage. Bill Belichick is 66. When McVay was born in January 1986, Belichick had just finished his first season as the Giants defensive coordinator. His sorcery on Bill Parcells’s staff—most notably during the Giants’ 1987 and 1991 Super bowl victories—started the Belichick mystique. Three decades and six titles later, his dismantling of the Rams offense in Super Bowl LIII rivals any achievement that came before it. Not to be outdone, 71-year-old Rams defensive coordinator Wade Phillips also brought his fastball Sunday. L.A. held the Patriots offense—which was led by 42-year-old coordinator Josh McDaniels—to just 13 points, and Phillips turned in his best game-planning performance of the season.

As defensive coordinators try to devise ways to slow down Goff, Mahomes, and the other offenses that have led the NFL’s points bonanza, they’ll likely study what Phillips and the pairing of Belichick and Patriots defensive coordinator Brian Flores used in the Super Bowl (and in the Pats’ case, the AFC championship game against Kansas City). They’ll find that there is no single schematic cheat code to unlock what those staffs did. In this era of offensive explosion, the biggest key to defensive success is being malleable enough to shape a defense for any given opponent—and aggressive enough to not allow efficiency machines like the Chiefs, Rams, and Patriots to ever get comfortable.

Phillips’s defenses have historically relied on a lot of man coverage, and, while the Rams used more zone schemes late in the season, they deployed a mixture Sunday that was designed to slow Tom Brady and the Patriots. The Rams used false indicators before the snap to confuse Brady, and, early in the game, he was having trouble distinguishing between man and zone looks. On Brady’s first-quarter interception to Rams cornerback Nickell Robey-Coleman, the signal-caller initially determined that L.A. was in man coverage—only for Robey-Coleman to fall off a receiver running down the seam and drift into the right flat to pick off a pass intended for Chris Hogan. The Patriots eventually found ways to gather information before the snap—they motioned running backs and brought receivers across the formation—but New England still managed only 13 points all game. That’s a testament to Phillips and his ability to disrupt a guy who’s seen everything.

The problem is that while Phillips’s unit flustered Brady, Belichick and Flores decimated McVay and his QB. Against the Chiefs in the AFC championship game, New England showed that it wasn’t content to sit back and let Kansas City play its version of the game. The Pats sent an array of different stunts at the Chiefs, and they continued that trend in the Super Bowl. Their pass-rush plan incorporated more pressure packages than the team typically uses. The Patriots increased their use of zone coverage and took a more extreme approach at the line of scrimmage on run downs.

Teams and coaches can learn some specific strategies from these Super Bowl game plans, but the biggest takeaway from what the Rams and Patriots accomplished Sunday is that flexibility and adaptability continue to matter most.

2. Let’s dig into some of the tactics the Pats used versus L.A., starting with their plan against the run. As the Rams built the most productive rushing offense in football, one of their biggest strengths this season was how smoothly their offensive linemen got to second-level defenders. No team did a better job scheming ways to quickly and consistently get its linemen onto linebackers. To combat that, New England removed its second level of defenders. In traditional rushing situations, the Patriots countered with a six-man defensive line. They played with four down linemen (which consisted of a rotation featuring seven different players who saw at least 10 snaps), with safety-linebacker hybrid Patrick Chung playing on one end of the line of scrimmage and Kyle Van Noy on the other. By crowding the line and occupying each of the Rams’ offensive linemen, the Pats created plenty of traffic and opportunities for their guys to win one-on-one matchups.

Most defenses combat the Rams’ brutally efficient ground game by sending their linebackers screaming after Todd Gurley on the back’s first movement. But because McVay loves to use play-action, that approach can leave defenses vulnerable. Rather than have inside linebacker Dont’a Hightower head downhill at the first sign of run action, Belichick and Flores instructed Hightower to react to the run in a more controlled way; he stuck to the middle of the field, which slowed play and allowed him to maintain his coverage responsibilities on play-action throws. That hesitation was possible only because the Patriots had devoted so many bodies to their defensive front.

3. Along with having Hightower stay put more often than usual, the Patriots used a collection of zone defenses that occupied the middle of the field and forced Goff to make pinpoint throws. New England used man coverage on a higher percentage of its defensive snaps than any team in football this season, but that didn’t matter Sunday. For Belichick, each game might as well happen in a different dimension. The Patriots played a variety of zone concepts throughout the game, and many featured a “buzz” defender—a safety who comes into the box and roams the middle of the defense. Belichick and Flores also upped the difficulty by starting that lurking defender from various spots. Sometimes, that would be Chung walking up from a deep safety on the back end. Other times, safety Devin McCourty would start near the line of scrimmage and bail at the snap, like he did on a tipped throw from Goff midway through the first quarter that might have been intercepted if it hadn’t been knocked down. The Patriots did an excellent job disguising their coverages and forcing Goff to process most of his information after the ball was snapped. That led to slow release times and confusion, and New England used that hesitation to its advantage with a bevy of line stunts and games up front.

4. Without a stable of dominant traditional pass rushers, the Pats manufacture pressure through their scheme, and they pulled that off beautifully during this season’s playoffs. On the Rams’ first obvious passing down of the game—a third-and-8 from their own 29-yard line—McVay’s offense lined up in shotgun with three receivers to the right and tight end Gerald Everett as the lone receiver wide to the left. New England responded with a four-man front that featured Hightower as a stand-up defensive end and Adrian Clayborn aligned as a 3-technique tackle, both to the right side. With fellow defensive tackle Malcom Brown aligned head-up on the center, the Rams should have anticipated some type of game between Clayborn and Brown, but they didn’t. The pair executed a quick twist stunt that got Clayborn loose as a free rusher, and, as Goff released a throw to receiver Josh Reynolds, he was hammered by the 280-pound lineman. It was the first shot Goff took Sunday, but it was far from the last. New England hit the Rams quarterback 12 times, and, like Clayborn’s lick, many of them were flush.

5. The second half of the Pats’ pass-rush plan was to regularly send five or six defenders on obvious passing downs. New England’s blitz-happy ways led to a pair of massive moments. One of those came from Duron Harmon, the reserve safety forced into a larger role when Chung left the game in the second half with a broken arm. In the moment, Ringer colleague Kevin Clark and I joked that Harmon would almost certainly become one of the largely unknown heroes for another Patriots championship team, and, sure enough, that happened late in the fourth quarter. One play after helping break up a would-be Rams touchdown to Brandin Cooks, Harmon lined up in the box. At the snap, he blitzed as part of a Cover Zero pressure designed to force a quick—and bad—decision by Goff. With Harmon bearing down, Goff floated a pass to Cooks that was easily intercepted by Stephon Gilmore. Just like that, the game was ostensibly over.

The other massive moment came courtesy of Hightower, who continues to show up at the most crucial moments. On a third-and-7 late in the third quarter, the Rams lined up in a shotgun formation with Hightower as a stand-up linebacker situated on the outside shoulder of guard Austin Blythe. With fellow linebacker Kyle Van Noy also threatening as a blitzer, the Patriots had five rushers against the Rams’ five offensive linemen, which ensured single blocks for each one of their defenders. At the snap, Hightower hit a quick inside move against Blythe, broke into the backfield, and pulled down Goff for a 9-yard loss. The sack came one drive after a third-down pressure from Hightower forced Goff into an incompletion from his own 6-yard line. On that play, Hightower was lined up as a defensive end on the left side, and there was nothing complicated about his path into the backfield. He simply beat Rob Havenstein—one of the league’s top tackles—with excellent hand usage on a power move.

The do-it-all linebacker missed last year’s Super Bowl with a pectoral injury, and his performance against the Rams was a reminder of just how vital he is to the Pats’ defensive versatility. There just aren’t many players who can adeptly fill both an off-ball linebacker role in running situations and that of pass rusher on throwing downs. The key to New England’s plan on defense is how many different ways it can use certain players, and Hightower epitomizes that philosophy. The Patriots’ ability to unearth playoff performances like this—surprising ones from their lesser-known players and consistently excellent ones from their key contributors—is the reason they’re in this position every year. And it’s the reason, no matter how much the roster turns over, they’ll be here until Belichick decides he’s done.

6. As Hightower and others have long showed, no player is too big for a certain task or a role in the Patriots system. That attitude also extends to New England’s offensive approach. The Patriots don’t care how they move the ball. It doesn’t have to be via some genius new route combination or gorgeous shot play down the field. If short throws to the flat are open—which they often were Sunday—Brady is willing to take them every time. If New England has to run the ball 30 times in a game because it’s the best approach, McDaniels will make the call. And if he has to call the same play three times in a row, he will. That’s precisely what happened on the most important drive of the Patriots’ season.

Starting with a first-and-10 play from their own 49-yard line with 8:50 remaining in the fourth quarter, McDaniels dialed up a pass concept called “Hoss Y Juke” on three consecutive snaps. The play involves a seam route by the tight end (in this case, Rob Gronkowski), combined with a route in the middle of the field by the team’s quickest receiver. Against split deep safety looks like the ones the Rams were using, the middle linebacker is responsible for the slot receiver. And as New England saw on a 13-yard completion to Julian Edelman on first down, linebackers don’t have much hope against Edelman in the open field. Two plays later, with Cory Littleton zeroed in on Edelman going in motion, the linebacker was late to Gronkowski running down the seam, and the resulting 29-yard completion set up the Patriots’ game-winning touchdown.

Beyond showing McDaniels’s focus as a play-caller, calling that particular play three straight times is notable because it’s a tried-and-true staple of New England’s Erhardt-Perkins offensive system. Over the years, several different players have cycled in and out of the role of a quick receiver who can take advantage of linebackers in space: At times, it was Wes Welker; others, it was Aaron Hernandez. The physical profile of players at that position has changed, but the concept has remained the same. That’s a testament to how adaptable the Patriots’ system is—and how they create constant mismatches for their players. Edelman was given every opportunity to roast various defenders with routes in space on Sunday, and taking advantage of those chances is the reason he was the Super Bowl MVP.

But the most remarkable part of this entire three-play stretch might be which New England skill players are on the field and where they line up. Most teams wouldn’t ever consider using an empty backfield with a fullback on the field. The Patriots did it three plays in a row. On top of that, the only alignment that remains the same on all three plays is that Edelman is always the no. 3 receiver (lined up farthest inside to the three-receiver side). And even that element gets tweaked when Edelman motions to that spot on the middle play. This team goes to ridiculous lengths to dress up the same concept in different ways.

7. Brady’s clutch throw to Gronkowski is the play we’ll be seeing for years, but I may have liked the first completion to Gronk on that drive even more. It’s a quintessential Patriots design. On first-and-10 with 9:49 remaining in the game, the Pats lined up with two backs in an I formation, two receivers split to the left, and Gronkowski as the in-line tight end to the right. New England loves to use play-action out of heavy formations in running situations, and it works like a charm here. At the snap, fullback James Develin and running back Sony Michel give a hard play fake, which sucks safety John Johnson into the box and leaves the defense’s back left side empty. After feigning a block, Gronk sweeps his arms through to get a clean release, and Brady drops a gorgeous touch throw over the top for an 18-yard gain. It’s the type of play we’ve seen from those two hundreds of times, but when it’s run that well, it never gets old.

8. Given the Rams’ lack of offensive success on Sunday, Gurley’s limited work as a runner makes some sense. But I still don’t understand how a back with his receiving skills gets two targets in the Super Bowl. Following the game, McVay was adamant that Gurley was completely healthy and that his usage was a product McVay’s own failure to find ways to work him into the plan. “I was not pleased at all with my feel for the flow of the game, and kind of making some adjustments as the game unfolded and giving ourselves a chance to have some success and put some points on the board,” McVay said. “Todd is healthy, and we just didn’t really get a chance to get anybody going today offensively, and that starts with me.”

Given that the Pats blitzed on half of the Rams’ dropbacks, it would seem to follow that at least a screen pass or two to Gurley would have gotten him loose in the open field. But by my count, one of the most efficient screen teams in the league didn’t throw one the entire game. The lack of initial penetration from the Patriots’ front and the horizontal movement in their stunts may have made McVay wary about throwing any screens, but when I asked him about Gurley’s lack of work in the passing attack after the game, his answer didn’t provide much insight: “When you do decide to activate some throws, what are the ones that give us the best chance to have success while not putting us in a position where you are getting those pick-stunts and different things like that, if you still want to keep that regularity? The film is always a good chance to go back and look at it, and I know there are a handful of decisions that I am going to want back for sure.” If Gurley really was healthy in the playoffs (and he certainly looked it in the Rams’ divisional-round win over Dallas), then his deployment over the past two games remains one of the biggest mysteries of the season.

9. For the most part, the broader legacies associated with the Patriots dynasty were already established before these playoffs even started. But what Dante Scarnecchia accomplished with the team’s offensive line during this three-game run is proof that he may be the most accomplished position coach the league has ever seen. After throwing shutouts against the Chargers and Chiefs, the New England offensive line finally allowed a sack against the Rams. But outside of that play, the pass protection was virtually flawless. The Pats blanked Aaron Donald and Ndamukong Suh, who combined for two QB hits the entire game. Two.

Scarnecchia has helped mold right guard Shaq Mason, whom many teams worried about as a pass blocker coming out of college, into a player worth a five-year, $45 million extension. Right tackle Marcus Cannon also rode his time with Scarnecchia to a sizable extension in 2016 (five years, $32.4 million). Mason and Cannon were drafted in the fourth and fifth rounds, respectively, and no member of the offensive line was taken before the 78th overall pick. Center David Andrews, who was excellent in the run game on Sunday, was an undrafted free agent. Left tackle Trent Brown was acquired via an offseason trade with the 49ers. A Patriots staffer told me last week that when the Patriots traded for Brown, they didn’t even know he could play left tackle. After sliding him into the starting lineup following an injury to first-round pick Isaiah Wynn, the Pats haven’t had to think about the position again. Scarnecchia is unparalleled in his field, and this season might have been the 70-year-old master’s best work yet.

10. This week’s line-play moment that made me hit rewind: When the Patriots need to hunker down and run to put games away, their line is happy to take over. As former NFL offensive lineman Geoff Schwartz pointed out during the game, double-teams don’t get more beautiful than this.

11. This week in NFL players, they’re absolutely nothing like us: Congrats, Jason McCourty. You’ll never have to buy a beer in New England again.