The way LeCharles Bentley sees it, the deteriorating quality of offensive line play in the NFL is an epidemic just like any other. Bentley, a former center for the Saints and Browns who now runs his own linemen training facility in Arizona, has watched the level of proficiency at the position group plummet in the past few years, and the search to pinpoint the crisis’s equivalent of patient zero pick up in earnest. “The natural tendency is to identify one potential culprit,” Bentley says. “But there’s always multiple factors that caused it to spread. It’s the same thing we’re seeing right now. Many are trying to look through a keyhole and see an entire hallway.”

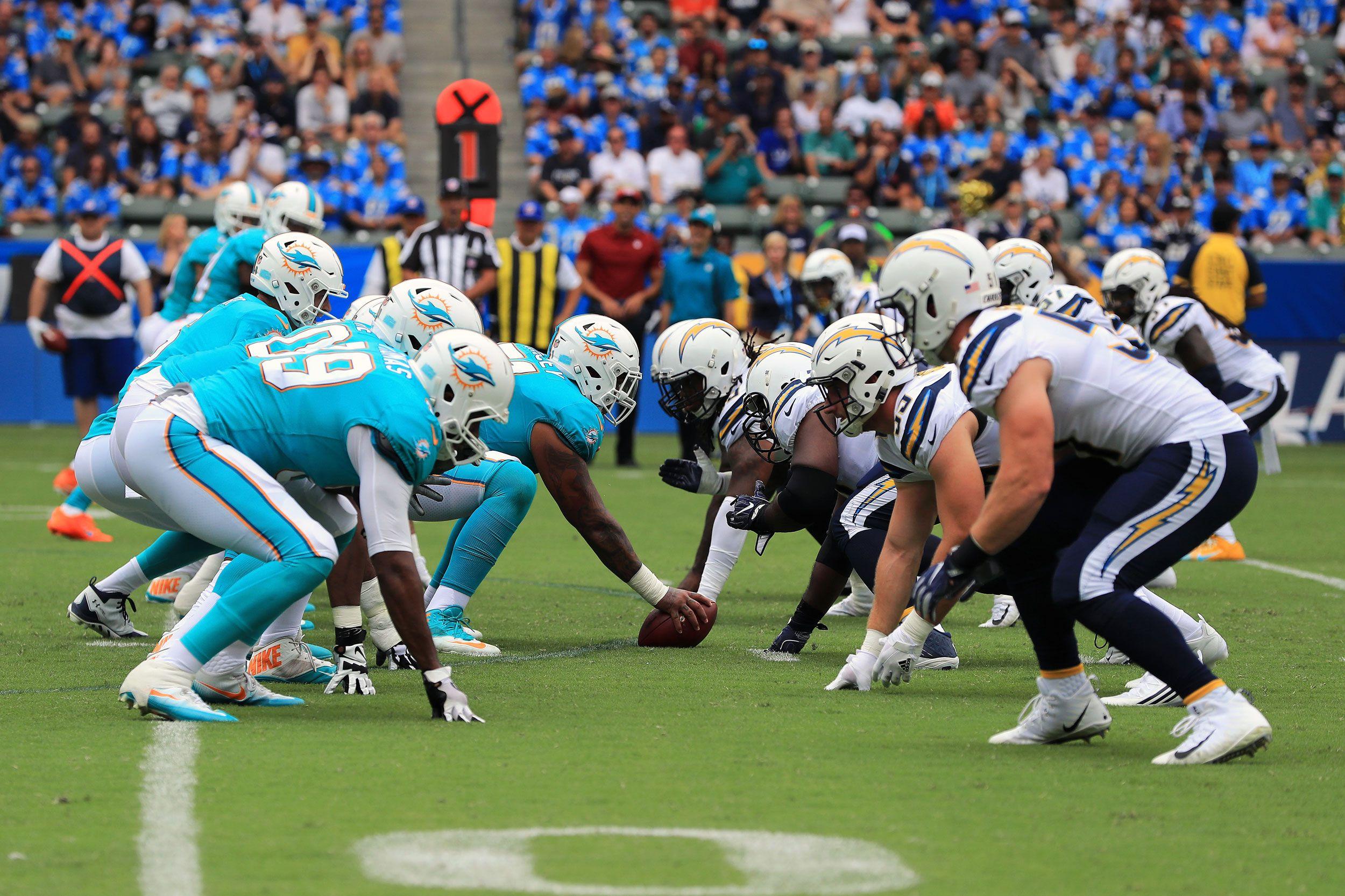

Those who are involved with offensive linemen in the NFL—from current and former players to coaches to executives—admit that the league is approaching a crossroads at the position. A shortage of effective linemen has affected the way offenses function, and blocking struggles have been the worst offender in creating the lackluster product on display at times during the first half of the 2017 season. Scoring league-wide has dropped from an average of 22.8 points per game last season to 21.9 in the first half of this fall, and teams are scoring fewer touchdowns per game (2.38) than they have since 2006. A collapse in offensive line quality has played a major role, and every expert has a pet theory for how it happened.

The rise of the spread offense in college football is a common villain, as many say that young linemen are entering the league less prepared than they’ve ever been. The limitations placed on team practice time under the new collective bargaining agreement is another. The truth is that the NFL’s state of offensive line emergency is likely the byproduct of several factors whose effects have all been exacerbated by the presence of the others. The evaluation and development of offensive linemen are being hit hard from several angles, and the cumulative impact has been devastating.

By exploring all of the influences and how they relate to one another, it may be possible to figure out how to combat them—and improve what we see on the field on Sundays.

Over the past few years, the spread offense has been stuck with a reputation as the NFL’s boogeyman, to the point that its proliferation in the college game has begun to feel like a tired excuse for failings at the professional level. Yet while teams across the league try to incorporate more spread concepts into their offenses, the approach’s effect on the development of young linemen has grown impossible to ignore. “It’s building block stuff,” Falcons offensive line coach Chris Morgan says of the deficiencies he sees in incoming linemen. “Now, there’s a little bit steeper of a curve with the stuff that used to be givens. You’re talking about guys hearing plays in a huddle, breaking a huddle, getting into a three-point stance, working combination blocks. You’re farther away than you used to be in terms of reps banked.”

If you’re running a spread offense in the college game, almost nothing translates to the NFL.Geoff Schwartz

The college game has started to move at such a rapid pace that it can barely resemble the sport played in the NFL. In January’s national championship game, for example, Clemson beat Alabama by running a whopping 99 plays from scrimmage; in last week’s thrilling 41-38 victory against the Texans, the Seahawks ran just 64. This trend has stunted the progression of linemen from a technical standpoint—guys in spread offenses constantly line up in a two-point stance, almost regardless of the situation—and, more crucially, it’s eliminated the complexity that’s long been inherent to line play. By operating at such a ridiculously fast clip, college offenses have negated the importance of the blockers up front making specific identifications and picking up intricate blitzes, which are skills that continue to be vital in the pros.

“If you’re running a spread offense in the college game, almost nothing translates to the NFL,” former NFL offensive linemen and current SiriusXM and SB Nation analyst Geoff Schwartz says. “You’re running at such a high tempo that teams aren’t going to twist and blitz because you’re moving so fast. Defenders are so tired.”

Titans general manager Jon Robinson says that the goal of many college practices is “going for quantity,” with teams using that time as a way to hone their ability to move lightning fast come game day. To wit: When Schwartz played at Oregon under then-first-year offensive coordinator Chip Kelly, he says that watching practice film had almost no value. The scout team could barely line up before the ball was snapped. And while college coaches doing their best Ricky Bobby impression is outrageously fun to watch, it’s caused linemen to lack technical skills and knowledge of schemes and protections that would allow them to smoothly transition from the NCAA to the pros.

As schematic differences have muddied both evaluation and development of college players, finding young linemen who have a baseline skill set has become more difficult. Figuring out which schools those players come from, though, has become increasingly apparent. A disproportionate number of starting NFL offensive linemen in recent years have come from a small collection of programs, and the percentage of quality linemen to emerge from that group is staggering. Wisconsin, for instance, has produced six starting NFL linemen in a pool of 160 players, including a pair of players (Kevin Zeitler and Rick Wagner) who reset the market at right guard and right tackle this offseason, a future Hall of Famer (Joe Thomas), and maybe the top center in football (Travis Frederick). Iowa boasts guys like Marshal Yanda, Bryan Bulaga, and Brandon Scherff, while Notre Dame counts Ronnie Stanley, Zack Martin, and his young brother, Nick.

Gleaning how these schools (and others like Ohio State and Stanford) have consistently churned out quality linemen comes down to a simple premise: By giving young players experience lining up in three-point stances and—in several of these cases, but not all—heavier formations that resemble those in the NFL, these schools move players further along in their development than most of their peers. Their education about what it takes to make it in the league doesn’t start from scratch. And given the barriers coaches now face in developing players after they’ve been drafted, the idea of finding linemen with strong starting points has become more attractive than ever.

The 2011 CBA restrictions that were placed on practice time have been a constant topic of league-wide conversation through the past few years. The area where that lack of practice shows up most noticeably is in the performances of offensive linemen, who aren’t even permitted to line up across from each other—with or without pads—during spring conditioning programs. “The way you fit blocks is different, the way you strike and punch,” Morgan says. “You can still work those things, but it’s like anything else—the less you do of it … you’ve got to really monitor the quality.” Limits on practice were instituted as a means of improving player safety, a worthwhile endeavor that’s unfortunately had a few unintended side effects.

According to Schwartz, the CBA change that’s most significantly hindered effective line play has been the ban on two-a-day practices during training camp. The offensive line is the only position group whose players literally have to work in step with teammates on every snap. Linemen are most successful when they innately know the habits and tics of players aligned next to them, and when they don’t get the reps needed to build that kind of rapport, the lack of familiarity eventually shows down the road. Schwartz cites a simple inside zone run with the right guard and the right tackle running a combination block on a defensive tackle lined up as a two-technique (directly over the guard) as an example. On the first time this play is run, the pair might botch the block. On the second, they might correct the mistake. On the third, the tackle could shift into a different gap. “That’s three separate plays,” Schwartz says. “We had a double-team we screwed up, we came back and fixed it, and all of a sudden, he moved. The fourth time, there’s a [defensive] pressure. The fifth time, the guys twist.”

When teams were allowed to have two practices per day in camp, there was adequate time for offensive lines to cycle through every possible variation and wrinkle that a defense could present—not only identifying it, but also facilitating an understanding of how the players would respond in real time. The same held true for linemen planning to stop blitzes or stunts in pass protection. “You don’t get as many reps anymore,” Schwartz says, “so I think when guys get to the game, a lot of players are surprised by movement and the things that happen.”

As the development of young players has become less reliable, teams’ desire to have veteran offensive line talent has naturally increased. And with this year’s draft almost entirely devoid of plug-and-play offensive line starters, needy front offices were pushed to the free-agent market and forced to pay 110 cents on the dollar as a result of overwhelming demand. Trying to keep tabs on the movement of 2017 free-agent linemen felt similar to watching an elaborate shell game. Top-end starters swapped jobs all over the league. After signing Rick Wagner as their new right tackle, the Lions let Riley Reiff walk; Reiff replaced Matt Kalil as the Vikings left tackle; Kalil signed a massive deal in Carolina, the team that the Vikings new right tackle Mike Remmers played for last season; T.J. Lang came to Detroit to be the new right guard; and the guy he replaced, Larry Warford, signed in New Orleans.

An offensive line is kind of like a marching band. Everybody’s got to do it in step.Larry Zierlein, Cardinals assistant line coach

For some of the teams that tried to replace veterans with young, highly drafted replacements, the results have been disastrous. The Bengals balked at the thought of making Zeitler the NFL’s highest-paid guard or paying a premium to retain 35-year-old Pro Bowl left tackle Andrew Whitworth this spring; Cincinnati currently ranks 30th in the league in adjusted sack rate, and both Jake Fisher and Cedric Ogbuehi haven’t looked like anything close to long-term answers up front. So far, the Cowboys have failed to replace the production of left guard Ronald Leary, who cashed in with the Broncos in March. With so much uncertainty surrounding the futures of each individual lineman, even the best-laid plans can go awry, which makes the background and experience of free-agent options all the more appealing.

Acquiring veterans has eliminated team concerns about how well players can grasp fronts, identify Mike linebackers, and protect. But this free-agency frenzy also has a drawback: Each seasoned player comes to his new home with habits and terminology learned elsewhere. “An offensive line is kind of like a marching band,” says Larry Zierlein, an assistant line coach for the Cardinals. “Everybody’s got to do it in step. [With free agents], you’ve got one guy doing a technique you learned in Baltimore, another guy doing a technique he learned in Dallas, and another guy doing something else.” Zierlein says it’s rare to see a starting five stay intact for more than a season or two these days. As the demand for free-agent linemen increases, so will player movement, ensuring a yearly game of musical chairs.

Therein lies the challenge in fixing the league’s offensive line problem: Every solution seemingly creates another issue.

One of the most confusing elements of the league’s offensive line crisis is how this shortage of quality linemen has coincided with the NFL’s athletes being better than ever before. “I think that’s where some of the mystery is coming in,” Bentley says. “Across the board, we have bigger, faster, stronger players, but the quality of [line] play has definitely decreased. I think now is the time when people have to start recognizing that [playing well on the] offensive line isn’t just about [being] a high-level athlete. It’s about being a high-level craftsman first.”

The size and speed of players around the league continues to increase, but that’s less impactful on the offensive line than it is at any other position besides kicker and punter. Because a majority of the skills that determine success are learned, the benefits that come from having significant athletic advantages are mitigated. “It’s such a technical position,” Robinson says. “You can’t just be big, move to the left, move to the right, and move straight ahead and be effective. It’s hand placement, it’s body coordination, and it’s playing with good power angles.”

You can’t just be big, move to the left, move to the right, and move straight ahead and be effective. It’s hand placement, it’s body coordination, and it’s playing with good power angles.Jon Robinson, Titans general manager

Further amplifying this problem is the set of players that offensive linemen are tasked with stopping. The benefits bestowed upon ludicrously athletic defensive linemen fall on the polar opposite of the spectrum. While the nuances of pass rushing are often understated, it remains a skill in which a rare combination of quickness and bulk can make up for a host of other blemishes. The uptick in physical gifts for defenders up front means that interdimensional beings like Myles Garrett and Jadeveon Clowney have entered the NFL. Even more problematic for offensive linemen is the sheer number of potential game wreckers who can be on the field at any one time.

The league’s premier defenses have gone from having one—or two, if they’re lucky—dominant rushers to trotting out three or four all at once. When the Jaguars can line up Calais Campbell and Malik Jackson on the inside while rushing Dante Fowler Jr. and Yannick Ngakoue off the edge, they present a terrifying prospect for opposing offensive lines. Deep, varied rotations in the front four mean offensive linemen have to be ready to handle a constant barrage of blitzes; with defensive coordinators constantly tweaking their alignments and moving guys to different spots along the line, it becomes only a matter of time before the weaknesses detailed above are exposed.

Zierlein points to Arizona’s Week 9 opponent, the 49ers, as a case study in what offensive lines are dealing with in 2017. San Francisco features a trio of former first-round picks on the defensive line: DeForest Buckner, Arik Armstead, and Solomon Thomas. “They will find a matchup. If they think your left guard is your weakest pass blocker, they’ll take their [best pass rusher] and put him inside. They don’t have to just be a tackle or an end. They’re looking for matchups.”

When a defense establishes that upper hand even briefly, it reveals one of the key distinctions between the realities of playing on each side of the line. “If you got one sack every game as a D-linemen, you’re a Hall of Famer,” Schwartz says. “If you give up on sack every game as an offensive linemen, that’s your last season playing.”

There was plenty to like about Jack Conklin going into the 2016 NFL draft, but Robinson says that what ultimately convinced the Titans to take the Michigan State product eighth overall was fairly straightforward. “When you put the tape on, it’s pretty simple: He blocked his guy,” Robinson says. “At the end of the day, that’s the most important thing for an offensive lineman. Whoever you’re supposed to block, you block him. It may not always look pretty. He may not look like the world’s best ballroom dancer out there, but he got on his guy, and he blocked him.”

This may sound like common sense rationale, but it sheds light on one final problem teams have encountered when trying to locate quality offensive linemen. Some of the worst draft misfires in recent years have come when high picks have been spent on offensive linemen whose vast potential has made it easy to overlook their fundamental deficiencies. The best example might be Lions tackle Greg Robinson, who was taken no. 2 overall by the Rams in 2014. Evaluators and coaches fell in love with Robinson’s size, strength, and mobility dating back to his days at Auburn, but that didn’t mean he was ready to be a consistent presence in the NFL. The same goes for the Giants’ Ereck Flowers, who’s disappointed in three pro seasons after being selected ninth overall out of Miami in 2015.

If you got one sack every game as a D-linemen, you’re a Hall of Famer. If you give up on sack every game as an offensive linemen, that’s your last season playing.Geoff Schwartz

There’s no denying that a ridiculous athletic profile is a component of some of the league’s best offensive linemen, especially at tackle. Lane Johnson, Joe Thomas, and Tyron Smith are three of the best athletes in the history of the position. The problem for offensive linemen, though, is that having that kind of uncommon athleticism is better served in helping a player reach his ceiling than in establishing an acceptable baseline for performance. As the league struggles to hone the skills of its offensive linemen—in part because of their background in spread offenses, in part because of their accrued lack of practice time, and in part because of myriad other factors—Bentley feels that it’s essential for teams to seek out players with projectable traits, even if those traits don’t necessarily blow people away. “[Coaches say], ‘I can’t develop this player,’” Bentley says. “Fine. At least [the traits that] I have on film from college are based on an identifiable, transferable skill set that at minimum is going to show up in the NFL. And in that reality, you usually have a player that can keep his head above water.”

The challenge for coaches and evaluators becomes determining which skills are transferable without much development. Bentley thinks this starts by examining the simplest stuff, like a player’s pre-snap stance, before then evaluating his understanding of angles and leverage. Zierlein primarily values intelligence, and not the kind that players can show by working on a white board. He wants to know how surprised offensive linemen will be when they’re presented with opposing twists and blitzes.

For Bentley, solving the game’s most glaring positional crisis has become about learning how to deal with the factors that have created it. “[Coaches] are never getting back more time,” Bentley says, “and they shouldn’t!” It’s up to decision-makers across the league to discern what type of players represent the best bets, and the stakes for getting that right are high: The quality of line play goes a long way in determining how much exciting offense appears on TV every Sunday. Other than unearthing a dozen great young quarterbacks, the NFL’s best path to avoiding unwatchable football is to create a larger pool of serviceable offensive linemen. It’s that pursuit that may have front offices changing what they look for at the position.

“Everyone’s on the market for a new car, and everyone has budgets for a Maserati,” Bentley says. “But the problem is when you’re trying a build a player and [considering] the climate we’re doing it in, putting a Bentley or a Maserati on a dirt road isn’t exactly the best way to go about it.”