In November 2005, Phoenix Suns coach Mike D’Antoni stood before his team at practice. Near him was Jack McCallum, an NBA reporter from Sports Illustrated. “You remember Jack from the preseason,” D’Antoni told the Suns. “He’s going to be with us a lot of the time working on, I don’t know, a book or something.”

Today, the mere mention of a season-with-the-team book would make CAA explode. But, in 2005, no Suns player refused to help with the book. No one’s agent said, “Shouldn’t this be a documentary series upon which my client exerts quiet but firm editorial control?” McCallum had a permission slip to get the material he needed. He’d gotten—this wasn’t yet such a dirty word—access.

McCallum spent the next seven months embedded in places NBA reporters were restricted from going. He flew on the team plane. He rode the bus. He sat in on coaches’ meetings. After games, McCallum followed the team into the locker room to get an unguarded look at Steve Nash and Shawn Marion and (when he deigned to appear) Amar’e Stoudemire before the rest of the media got in.

Today, reporterly acts like these, if they happen, are almost comically censored. By contrast, D’Antoni stopped McCallum from attending only a handful of meetings, like his late-season one-on-one with Marion. And D’Antoni occasionally said, “I’ll kill you if this is in the book.”

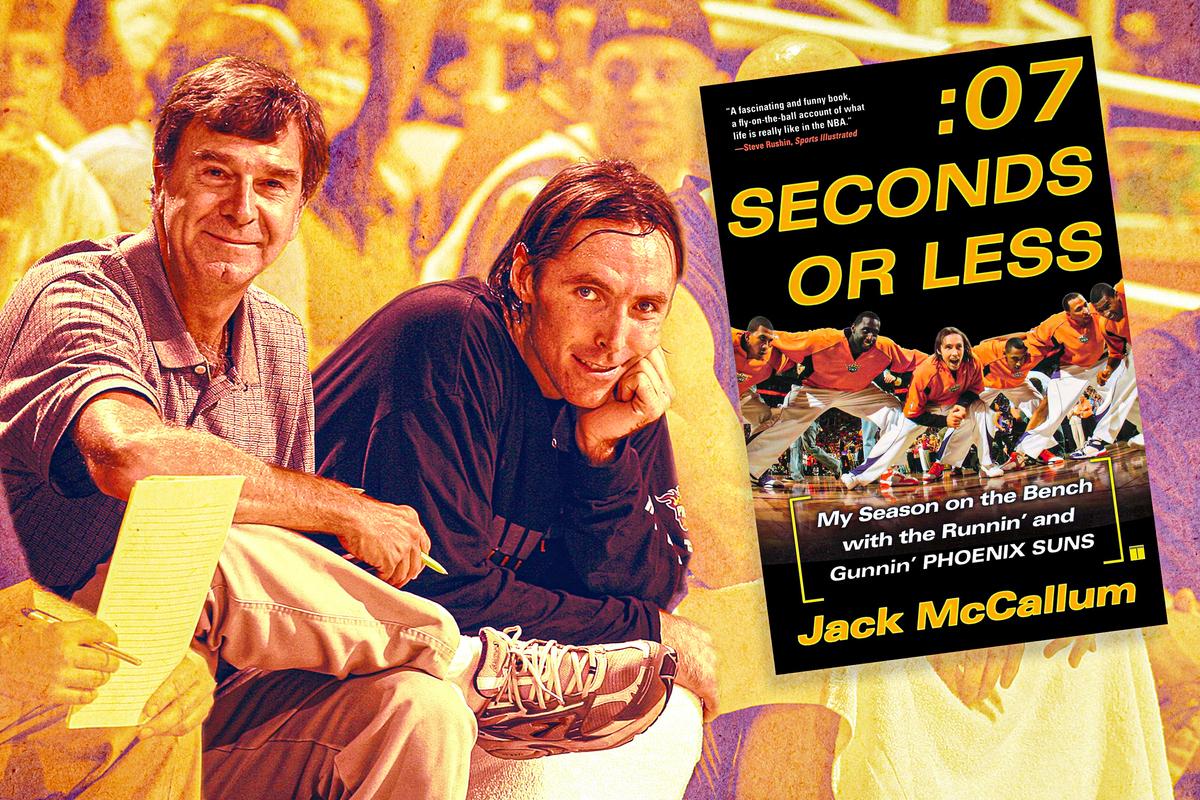

McCallum’s :07 Seconds or Less, published in November 2006, is an incredibly fun book to reread, and not just as history. This year’s Suns are again being carried through the playoffs by a brilliant point guard who you’re afraid will wear out. There’s also something interesting about revisiting the last time an NBA team really threw open its doors for a book. It shows you who got access and what it was good for.

If access has become a dirty word in sportswriting, it’s because there’s so little of it. At this year’s All-Star weekend, commissioner Adam Silver called an open locker room “a bit of an anachronism.” A writer who gets 30 minutes alone with an NBA player is presumed to be committing at least a journalistic misdemeanor. The writer will tell a one-sided story, do a solid for an agent, or turn an article into a native ad. (“Mikal Bridges talks defense, second chances, and NFTs.”)

There was a time when the NBA was different. The time was 1985, when McCallum became the lead NBA writer at Sports Illustrated. “Young reporters—which is pretty much everybody but me—can’t believe that the default position was you used to watch practice,” McCallum told me.

As the league got bigger and bigger, NBA writers like McCallum could see their free run through the locker room was ending. It was like an automatic garage door was closing. In the 1970s, The Boston Globe’s Bob Ryan had walked right in. By the ’90s, the Chicago Tribune’s Sam Smith was ducking his head slightly. In 2005, McCallum slid under the door before it closed for good.

McCallum, who was 56, first conceived of :07 Seconds or Less as a participatory magazine story. McCallum didn’t want to go through Suns’ training camp as a 3-and-D guy. He wanted to be an assistant coach. If that separated McCallum from the players, marking him as one of them, well, that was sportswriting after the turn of the century. If George Plimpton wrote Paper Lion today, he’d be Detroit’s passing game coordinator. He’d probably wear a visor.

McCallum published his SI story about the Suns coaches in October. Readers liked how chatty they were. McCallum asked if he could expand the idea into a season-spanning book. For a second time, the Suns said yes.

McCallum had lots of advantages beyond being an all-NBA-level reporter at a still-humming magazine. D’Antoni was OK with a book, for starters. The Suns’ PR director, Julie Fie, was one of the league’s best. Owner Robert Sarver, who’d bought the team a year earlier, wasn’t yet getting night sweats thinking about ESPN reporters Kevin Arnovitz and Baxter Holmes.

The Suns’ quick-strike offense (they wanted to get a shot up before seven seconds went off the shot clock) was a vision of the future of the NBA. “They were the league’s pet rock,” said McCallum. But the Suns still sat behind the Lakers and Spurs in the glamour-team power rankings. They had a small press corps. A book had upside.

McCallum arrived at America West Arena at a lucky moment in media history, too. The world didn’t yet know Woj bombs, Instagram stories, or Uninterrupted. The basic interface of NBA media was still a player talking to a reporter. That season, McCallum was around the players all the time. He said he spent $30,000 of his book advance traveling between Phoenix and his home in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

McCallum was not the type of writer to flaunt his access. He kept a Radio Shack tape recorder tucked in his pocket. At coaches’ meetings, he waited for an odd noise: D’Antoni scratching out a play on the blackboard, or Alvin Gentry taking his seat. Then–BANG!–McCallum hit record.

“Studying a coaching staff would be rich material for an industrial psychologist,” McCallum wrote in :07 Seconds or Less. McCallum, of course, took the psychologist’s job for himself. His perch gave him an unrivaled view of what NBA coaches actually do.

McCallum found Mike D’Antoni driving a Porsche Carrera, the perfect car for the architect of the Suns offense. D’Antoni had the irrational confidence of a maverick. “I’ll hear people say, ‘You blew a big lead because you play fast,’” D’Antoni said. “Well, hell, did they say that before we got an 18-point lead? Playing fast is how we got the lead.” An Orlando Magic scouting report said of the Suns’ offense: “Literally nothing is frowned upon.”

A number of fans thought NBA players were uncoached. In fact, McCallum argued, overcoaching had “removed much of the spontaneity of the game” and made it somewhat dull. By demanding the Suns push the ball–D’Antoni’s instruction seemingly before, during, and after every game–he was trying to restore the NBA to an ’80s ideal.

D’Antoni also demanded more 3-pointers. McCallum remembered him chewing out Suns players who didn’t stand deep in the corners like they were supposed to. In ’05-’06, the Suns led the NBA with 2,097 3-pointers attempted. This season, that total would put them more than 1,200 attempts behind the league-leading Timberwolves.

The Suns assistants—including Gentry, Marc Iavaroni, and D’Antoni’s brother Dan, a longtime high-school coach—were loose and funny. If you ever wondered why Gentry got NBA head coaching jobs—he’d had three by 2005, and would later get two more, plus an interim job with the Kings last season—read McCallum’s book. Gentry is one of the sharpest observers of the league. “That’s the NBA,” he said when David Stern was handing out uniform violations. “You get fined ten grand for grabbing a guy’s balls and ten grand for wearing your shorts too long.”

McCallum and his recorder captured lots of talk like that. In the playoffs, Iavaroni asked Boris Diaw for a reason he should play during overtime. Diaw couldn’t or didn’t answer. He went to the bench.

Another time, the coaches wondered if the Mavericks would start center Erick Dampier. Yes, D’Antoni said, because it’s “a rule that if you pay a bad player $70 million you have to start him.”

Suns assistants constantly stared into their portable DVD players and tried to solve problems. They had a lot of problems. That season, Stoudemire hurt his left knee during the preseason and his right knee during the season, and he was unenthusiastic about rehab. The Suns traded Joe Johnson to Atlanta after Sarver low-balled him in contract talks.

Suns assistants pelted D’Antoni with ideas. McCallum noted that one of D’Antoni’s gifts was repackaging these ideas. “For every minute of specific instruction D’Antoni gave his team … he and his assistants had spent at least three hours deciding on those specifics,” McCallum wrote. And the specifics almost always came with a smile. The “players’ tape” the coaches showed the Suns rarely included the team’s terrible plays, lest they get anybody down.

What NBA coaches do, it turns out, is make constant spiritual assessments of their team. During a game against the Spurs, Raja Bell ignored a play call from D’Antoni. D’Antoni got angry at him. “Raja, I apologize,” D’Antoni said in the locker room afterward. “We cool?”

No answer.

“Raja, we cool?” D’Antoni asked again.

Bell nodded.

D’Antoni and Bell met privately that night. Then, before the Suns’ next game, Bell apologized to his teammates for a different incident in the Spurs game involving Diaw. Only then had a nebulous but serious problem been solved, or at least put aside.

Some of the book’s best glimpses of the Suns coaches came after losses. “They snap at each other,” McCallum wrote. “Sometimes they order onion rings and French fries together.” When the Suns were a game away from being eliminated from the playoffs, the coaches wondered about adding Darko Milicic to the team the next season. That’s a good sign you’re out of ideas.

D’Antoni wore the burden of his job more lightly than Pat Riley did. Even so, McCallum was struck by how much it consumed his life. Once, McCallum noticed D’Antoni was distracted while watching a movie on the road. He asked what was on his mind.

“I’m trying to figure out how to stop Kobe,” said D’Antoni.

Season-with-the-team books have certain tics. A big play is described in detail—a last-second shot clangs off the rim. There’s a break in the text. Then comes the mandatory backstory: “Jeffrey John Hornacek had known disappointment before … ”

McCallum, thankfully, has a silkier touch. He’s maybe the only sportswriter who can reference Henry V and Falstaff without sounding pretentious. In :07 Seconds or Less, his mini-profiles of Suns players have a nice crackle, like those quotes from anonymous scouts that used to appear in Sports Illustrated. Only here the quotes are on the record and sourced to coaches.

Steve Nash, who won his second consecutive MVP that season, is as confident as his hair is long. “I don’t like to build maps,” Nash said when McCallum asked him where he preferred to shoot from on the floor. McCallum found Nash somewhat uncrackable. But he pieced together a portrait by observing Nash’s “camp counselor” vibe. After beating the Lakers in the playoffs, Nash was the guy who told teammates to skip the parties and get some rest. Before a game, when there were 19 minutes left until tip-off, Nash would tell the team, “Nineteen on the clickety!”

When asked by D’Antoni to speak at halftime, Nash inevitably told the Suns the same thing: They should jump on the other team early in the third quarter. “He was very frustrated he couldn’t get through to the team,” McCallum told me. “Maybe he feels the same way right now, in a different way.”

McCallum’s profile of Shawn Marion is even more interesting. McCallum found Marion in the shadow of the Suns’ stars, despite Marion averaging nearly 22 points and 12 rebounds that season. During timeouts, the Suns sometimes brought a drum line onto the court. Marion noticed the drummers were wearing Nash and Stoudemire’s jerseys, but not his. In the first round of the playoffs, the Suns won a big overtime game against the Lakers to stay alive. “We win, it’s everybody but me; we lose, it’s my fault,” Marion told McCallum in the locker room afterward. “I don’t understand that.”

Marion wasn’t wrong. When Nash played poorly, D’Antoni excused it because Nash was out-physicaled. Because Marion was a terrific athlete, D’Antoni said, his errors could “sometimes be tied to lack of hustle or desire.” You understand why Marion thought that was a no-win situation.

McCallum found stories up and down the roster. Stoudemire played only three games in 2005-’06. He still declared of Kevin Garnett: “You know, KG can’t carry a team like I can.” Boris Diaw, in his breakout year, played brilliantly in a one-on-one workout against Stoudemire. “Boris brought the French pastry on Amar’e’s ass,” said Eddie House. Then there’s Bell, now a Ringer podcast host, who gave Kobe Bryant a Jake “the Snake” Roberts DDT during the playoffs. “It’s like it happened in slow motion,” Bell told McCallum a day later. “‘All right, Rah-Rah, don’t do it. Don’t … you’re going to do it … you’re going to do it … SHIT! You did it.’”

McCallum crammed a lot of House into the book. Awesome. House once explained why he didn’t leave many tickets for friends to come to games. “I mean, you can look for your parents in the crowd and shit,” said House, “but you can’t be looking for specific motherfuckers.”

Speaking of specific motherfuckers: Suns owner Robert Sarver flits in and out of the book. He’s like a Mark Cuban cosplayer. Sarver hangs out with the coaches. He wears ripped jeans. He tries to keep L.A. fan Penny Marshall away from his players. (“This is war!”) In one of the book’s funniest scenes, Sarver tells McCallum his eyebrows are overgrown. “Excuse me?” McCallum says. Later, Sarver takes a pair of scissors and trims McCallum’s eyebrows himself. Now that’s access.

“The beauty of a book is the little things that happened,” said McCallum. Indeed, my theory about season-with-the-team books is that they’re best enjoyed as scrapbooks. Just about every page of :07 Seconds or Less has an observation or line that would redeem an oral history in The Athletic.

Before Suns games, the team’s wings had a meeting. At the end of the meeting, the wings yelled, “WANGS!” That is a wonderful detail. Before games, D’Antoni listened to Pink’s George W. Bush–era anthem “Dear Mr. President” as his hype music. Mike, welcome to the resistance.

Actor Jim Caviezel, fresh off The Passion of the Christ, chatted with Stoudemire at a Suns practice. (“Black Jesus meets White Jesus,” one coach said, referring to Stoudemire’s tattoo.) Jack Nicholson told D’Antoni that Kobe Bryant is “great, but he tries to do too much.” (“Well, we could debate that,” D’Antoni replied.)

“These are the times that try men’s souls,” D’Antoni told McCallum at one difficult point during the playoffs.

“Thomas Paine,” said McCallum, recognizing a famous line when he heard one.

“No,” D’Antoni replied, “I’m pretty sure it’s Phil Jackson.”

To reread :07 Seconds or Less is to revel in the details McCallum hoovered up with access. It also reminds you that, in 2005, access was something players were expected to offer but didn’t have much of themselves. Let’s say Shawn Marion had a problem with D’Antoni. What was Marion going to do? Plead his case to The Arizona Republic? Let ’er rip in a postgame interview, and hope the message passed unfiltered to SportsCenter? Unload to a national NBA reporter who swung through town? Taking any action would have gotten Marion tagged as a complainer, a “cancer,” or worse.

The Suns’ powerlessness versus the media was almost comic. During the ’05-’06 season, Charles Barkley blasted his old team on TNT. The Suns—including Nash, the reigning back-to-back league MVP—didn’t have a platform they could use to fire back like Kevin Durant did last week. The Suns’ only recourse was to remove a photo of Barkley from the ’93 Finals that hung in team headquarters.

On June 3, when the Mavericks finished off the Suns in the Western Conference finals, McCallum entered the locker room with the coaches. D’Antoni asked Nash to speak, but Nash was crying. Today, a player’s goodbye message would be posted on social media or perhaps stuck in a Man in the Arena–style doc. McCallum had the locker-room scene all to himself.

I read those passages with extreme sportswriterly envy. I hate that reporters don’t have exclusives like that much anymore. But I also understand why players don’t want us to.

McCallum’s last act of journalistic infiltration happened the next day. D’Antoni let him sit in on Nash’s season-ending exit meeting. D’Antoni and Nash talked about trades the Suns could make and about Nash’s load management. They hugged. Nash even hugged McCallum.

“Jack,” Nash said, “now you can fuck off.” It was a message for all of us. The garage door had closed.