They can tell he is falling by the cameras. As Michael Porter Jr. sits at a table on the floor at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center, his family watches as a camera crew floats around the NBA draft’s greenroom, filming other men surrounded by other families as they experience the great joys of their lives. Porter’s brother, Jontay, sees Porter’s agent, Mark Bartelstein, fielding calls and texts, his parents offering encouragement, Porter himself racked with anxiety, much of the table watching to see where the cameras go next.

Little more than a week before, Porter was hearing from teams near the very top of the draft. They liked him, they said. They liked his size and athleticism, his ability to score from inside or out. He’d been the no. 2 player in his high school class, a 6-foot-11 forward with hops and range. Even after a back injury limited him to only 53 minutes of college ball at Missouri, Porter still looked like a mid-to-high lottery pick. And then, seven days before the draft, Porter did not work out during a second scheduled pro day, dealing with a strained hip. The concerns that teams already had over his injury grew. Maybe, they reasoned, his health problems would overshadow his All-NBA potential.

So Porter sits in a baby-blue suit stitched with family names and words of inspiration on the inside, and he watches and waits. For many picks, his agent gets word from the teams before their selections are announced. For others, Porter doesn’t know for certain until he hears the words come out of commissioner Adam Silver’s mouth. For all, he watches the cameras. They tell the future.

With Sacramento on the clock at no. 2, they drift to the table of Duke’s Marvin Bagley III. Porter had beaten Bagley in high school. In the days leading up to the draft, the Kings had been rumored to be considering Porter before settling on Bagley as their man.

When Chicago comes up at no. 7, the cameras lock on Duke’s Wendell Carter Jr. All week, Chicago media have been asking Porter about the possibility of his coming to their city. In high school, Porter had been ranked three spots above Carter in ESPN’s recruiting rankings.

While the crowd chants, “We want Porter,” ESPN’s cameras hint that Knicks fans will not get their wish. They set up in front of Kentucky’s Kevin Knox, who’s been slotted below Porter in virtually every mock draft.

Soon come the Clippers, whose owner, Steve Ballmer, attended several of Porter’s games at Seattle’s Nathan Hale High School. They trade up one spot to take Kentucky’s Shai Gilgeous-Alexander at 11, then select Boston College’s Jerome Robinson at 13.

Porter says he knew—not just believed, but knew—that he was bound for the NBA ever since he’d been in fifth grade, when his AAU team won nationals with him as the star. In high school, he’d drawn comparisons to Kevin Durant. Even as he sat out most of his lone season at Missouri, he remained a lottery prospect.

“I’ve played the moment out in my mind so many times,” Porter told me the day before the draft. “That handshake, those hugs with my family, walking onstage in that suit.”

Never, though, has he spent much time fantasizing about this. As the lottery nears its conclusion, he remains seated. With Denver set to pick at no. 14, cameras settle right in front of his table. At almost the exact same moment, Porter’s agent receives confirmation.

Finally.

Michael Porter Sr. and his wife, Lisa, are the parents of eight children, and from the time the Porter kids were toddlers, each one had a basketball in his or her hands. Michael Sr. would run them through what he calls, “fun, age-appropriate” drills. The Porters had a small court in their backyard in Indianapolis, and Michael Sr. would set up boxes a few feet apart and encourage them to dribble around them, alternating between right and left hands. He lowered the basket to its lowest possible height, then taught them to shoot with proper form. “I didn’t want them heaving it,” he says. “Kids that age aren’t strong enough, so they start bending down and shooting from their waist.” He’d heard a story that Eric Gordon’s father hadn’t let him shoot 3s until the fifth or sixth grade, when he was strong enough to shoot correctly. With his children, Michael Sr. did the same.

Both parents had played college ball—Lisa at Iowa, Michael Sr. at New Orleans. Michael Sr. later joined the Christian organization Athletes in Action, traveling the country playing exhibitions and spreading an evangelical message. By the time the younger Michael was 5 years old, his older sisters Bri and Cierra had already established themselves as clear talents, and his father was coaching in Upward Basketball, a Christian youth organization. The Porters homeschooled their children, and in between classes they would hit the court, running through drills on their own or with their father, day after day. “I hated playing against him,” says Jontay about Michael Jr., who’s the older brother by about 16 months. “He always took it so seriously, and I was just trying to have fun.”

After winning AAU nationals in fifth grade, Porter says he knew he was destined for the NBA. His father didn’t get that clear sense until a few years later, when Porter, as a 6-foot-5 eighth-grader, dominated against some of the most talented players in his age group at a summer camp run by former NBA player John Lucas. After he hit a silky, stepback jumper, one of the coaches turned around and said, to anyone who would listen, “That kid is a pro.”

Jontay, a projected first-rounder in the earliest of 2019 mock drafts, remembers that camp as well. “Michael was like a rock star,” he says. “He was skinny but getting buckets on kids that were way more physically mature. I just thought of him as a basketball god.” Porter rocketed onto the high school basketball scene, playing AAU alongside fellow future lottery pick Trae Young for the team Mokan Elite. Together, they won the 2016 Peach Jam. A year later, both were McDonald’s All Americans; Porter was also named MVP. (Young, who was drafted nine spots ahead of Porter and ended up in Atlanta after a trade, laughed when asked about his former teammate the day before the draft. “I played a lot of one-on-ones with him in high school,” he said. “I didn’t play him in college. He don’t want to see me. He knows what happens when we play one-on-one.”)

After beginning high school in Missouri, Porter moved during his senior year to Seattle, where he returned to being homeschooled while playing for Nathan Hale High. He dominated, averaging 36 points and 14 rebounds while leading his school to a 29-0 record and a state championship. “He could do whatever he wanted,” says Jontay, who also declared for the 2018 draft but pulled out in late May. “I always thought he was going to make the NBA, but that year I started to think he could be one of the best players ever.”

I hated playing against him. He always took it so seriously, and I was just trying to have fun.Jontay Porter

Jontay, who at 6-foot-11 and 236 pounds projects as a more traditional big man, points to his brother’s work ethic as part of what sets him apart. “He has the greatest work ethic I’ve ever seen,” Jontay says. “When we were younger, honestly, I didn’t have the greatest work ethic. But just watching him and seeing how hard he worked, I knew that was what it took to be as good as him. So that challenged me to start putting in the time, working out in the gym constantly like him.”

Says Michael Sr.: “It’s easy to call him ‘focused,’ but honestly, it’s not even that. He doesn’t even have to make the effort to be focused, because he just loves being in the gym. Getting him to put in the time it takes to be great has never been hard.”

Porter originally committed to Washington to play for Lorenzo Romar, a longtime friend of his father’s, and his father himself, who was then an assistant coach for the Huskies. After Romar was fired, Cuonzo Martin hired Michael Sr. to join his staff at Mizzou, and Porter Jr. committed to join them. Jontay reclassified, graduating a year early so that he could join the Tigers too. “I knew he was going to be one-and-done,” Jontay says. The Porters returned to Columbia with massive expectations. USA Today ranked the Tigers 24th in its preseason poll and called Porter “a Kevin Durant–esque player.”

Before the season started, Mizzou played longtime rival Kansas in a charity exhibition, and Porter scored 21 points and grabbed eight rebounds in 23 minutes of a 93-87 loss. “Michael is a terrific, terrific talent,” Kansas coach Bill Self said afterward. “If you guard him with a guard, which we did almost the whole time, that’s hard, because he can take you to the post. He was able to do that a couple times. If you guard him with a big, he’s so good behind the arc, and that puts a big in jeopardy.”

Porter never reached that level in a Mizzou jersey again. Over his last two years of high school, he’d dealt with discomfort in his legs and hips stemming from an issue with his back, and the pain lingered into preseason camp with the Tigers. “I could always just play through it,” Porter tells me. “It never got worse, so I kept going, with stretches and treatment and physical therapy. The preseason was good—bad days and good days.” And then, he says, “it took a turn for the worse.”

About a week before the season opener, Porter told his father, “My leg feels dead.” He kept practicing, confident he’d be ready to play. Minutes before the team’s season opener against Iowa State, Porter realized he couldn’t do it. He told coaches he should sit. The team had already turned in its starting lineup to the scorer’s table, though, so Porter took the floor, scoring two points and grabbing one rebound in the first two minutes of the game. Then, at the first dead ball, he came out, never to return.

He needed back surgery, a microdiscectomy on his L3 and L4 disks. “That was absolutely crushing,” Jontay says. “I mean, I just know how crushing it was for me. So I can only begin to imagine how crushing it was for him.” Porter’s rehab was scheduled to take three to four months, likely keeping him out for the rest of the season. “Those were hard days,” Porter says. “Really hard days.” Yet he now tries to look back on that period as time he needed for himself, “to get solid in who I am.” He read. He took up fishing. He spent many nights in a Bible study with his siblings and several friends.

The fact that he played in those games shows that he was thinking about the rest of our team. The message that night at Bible study was about what we should do for others rather than ourselves, and really, I think that’s the biggest theme of Michael’s whole year at Mizzou.Jontay Porter

It was there, sitting in that Bible study in late March, that Porter decided he wanted to play again. He’d been in rehab for months, working toward a return. Even though he wasn’t fully healthy, he’d found himself regaining slivers of his old burst and spring. That night, he remembers a discussion about God giving people talents to use for others, not for themselves.

Porter knew that if he returned to the court, his physical limitations would likely keep him from reaching his own hype. And yet, he thought, even if he wasn’t healthy enough to dominate, he was still healthy enough to compete. Jontay remembers riding home with his brother that night, talking. “‘Even though I’m not 100 percent,’” Jontay remembers as Porter’s thinking, “‘I can still help the team. I shouldn’t be worrying about my draft stock. I should be worrying about my team.’”

He returned and underwhelmed—12 and 8 in an SEC tournament loss to Georgia, then 16 and 10 in an NCAA tournament loss to Florida State, shooting 31 percent across the two games. After 53 minutes and 30 points, Porter’s college career was over. He declared for the draft 10 days later. “To me, the fact that he played in those games shows that he was thinking about the rest of our team,” Jontay says. “The message that night at Bible study was about what we should do for others rather than ourselves, and really, I think that’s the biggest theme of Michael’s whole year at Mizzou.”

Jontay explains further: “When we were in high school at Nathan Hale, some people looked at him and thought he was doing things for himself. We played ‘Michael-ball’ a little bit. He cared a lot about how he looked and what he did. But learning how to be a good teammate is vital, and I think he really did that at Mizzou. He wasn’t on the court, but he was a leader and an encourager for everyone.”

“I’m the best player in the draft.”

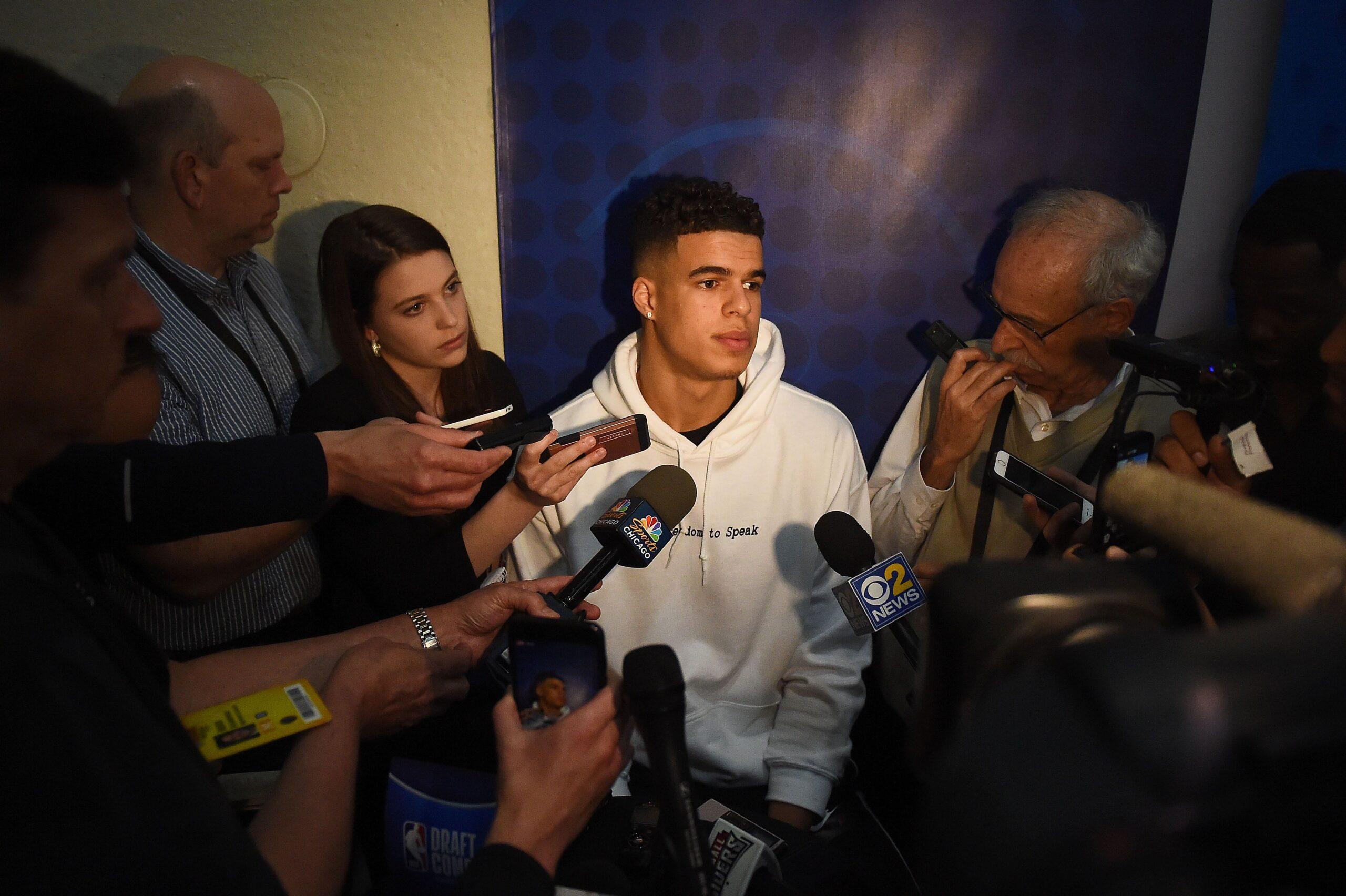

Porter first said it in May, while doing interviews around the combine. He said it again a day before the draft, while surrounded by reporters in New York on Wednesday. “I think every player in the draft—especially in the top 10—should feel they’re the best player in the draft,” he said. “So yes, I feel like I’m the best player.”

You can make a case. Porter was long considered the best player in his high school class, supplanted only when Bagley reclassified from the high school class of 2018. Nearly 7 feet, Porter seems perfectly built for the positionless NBA, able to handle on the perimeter and score from any spot on the floor. He’s shown good athleticism on the boards, if lacking in strength, and good instincts on defense, if lacking in toughness. Watch his DraftExpress scouting video and you’ll see plenty of flashes of a star. When asked for the best draft classmate he’s faced, Bagley didn’t hesitate. “I would say Michael Porter. … Every time we play against each other it’s a battle,” he said. “He can do a lot of similar things to me—shoot the ball, go inside or outside.”

By the time draft week arrives, though, it has become clear that Porter has no shot at going first. The Suns seem set on taking Deandre Ayton. Yet speculation remains that Porter could go anywhere from no. 2 onward. So at his predraft presser, he fielded questions from reporters across the country, asking how he would fit with their team. Sacramento seems like “a kinda mellow” city. Chicago resembles “a smaller, less busy New York.” The chance to play for the Knicks in Madison Square Garden is “dope,” he says, and as a vegan, he feels confident he can resist the urge to try the city’s pizza. Three different reporters asked questions about the 76ers, and to all, he says he believes he would fit in “great.”

A few minutes after his presser, Porter wandered upstairs to a quiet corner on the mezzanine level at the Grand Hyatt Hotel. “Honestly,” he said, “this is exhausting. But I’m trying to make it as fun as I can.” Porter calls himself an introvert. And while draft week may be exciting, it can feel like an assault on a player’s solitude. There have been endorsement appearances and charity functions. Suit fittings and phone calls from teams. Endless interviews, most with the same questions. Everywhere, new strangers to meet and smiles to deliver. At one point, I watched an NBA Cares staffer approach Porter while he was seated in a gym at a service project and joke that he should correct his posture so as not to further injure his back.

There were reports that questions about his health affected Porter’s stock more than anything else. Yet a few draft analysts reported whispers that he might have a bad attitude, might not be fully invested in his teams. “I don’t really know where that comes from,” Jontay says, “but if it came from anywhere, it’s high school—not Mizzou.” Michael Porter Sr. admits that he sometimes worried about his son’s relationship with social media, that he had moments when he fell too deep into the comment streams of unrelenting praise. “He got sucked in sometimes,” Porter Sr. says. “He was an eighth-, ninth-, 10th-grader with thousands of people telling him how great he was, and as a person without much life experience, you can get fooled into thinking those people are your friends and really care about you. And sometimes he might have based how he felt about himself on the likes and the comments and everything else.”

Draft prep could be a slog. Particularly since, for Porter, it began with his surgery and rehab last fall. “I’ve been anxious,” he told me the day before the draft. “You go through this whole process, and then you just wait for someone to tell you what city you’re going to live in, what teammates you’re going to play with, what coach is going to coach you. I just want to know.” Still, he tried to enjoy as many moments as he could. He felt thrilled by the experience of his pro day. “Just being back on a basketball court in front of people,” he said. “Even though it wasn’t a game, it was so good just to show people who I am and what I can do.”

Sitting in the Hyatt, Porter admitted to some fatigue. He said he respects and appreciates the media but admitted to growing a little weary. The day before, he’d mentioned comparisons to Durant in another interview. He phrased it awkwardly, making the comparison himself before calling it an honor, and blogs had run wild. “All of that is crazy,” Porter said at the Hyatt. “I’m just trying to answer questions, and you never know when something you say is going to get twisted a little bit and turned into something else.”

All week, he has existed as the draft’s greatest mystery, a player with the widest range of potential landing spots and the widest range of potential career trajectories. He could wind up as an MVP or as someone who plays fewer than 100 career games. To anyone who will listen, Porter insists that he is ready, that his body feels great. And as he reflected on the path that brought him to this moment, he did his best to express gratitude for even the most painful experiences. “A lot of this didn’t happen the way I dreamed it would,” he said. “This wasn’t the plan. But I genuinely believe that I needed to go through all of this. It’s just going to make me that much more ready for the next step.”

Minutes after shaking Silver’s hand, Porter slips off the arena floor and into its lower hallways, Nuggets cap on. All night, this area has been the scene of celebrations—bro hugs between draftees, copious amounts of dap delivered by Jazz guard Donovan Mitchell, and the sight of Jaren Jackson Jr., the no. 4 overall pick by the Grizzlies, yelling at no one in particular, “I’m so hyped!”

But Porter walks quietly, cellphone attached to his ear, looking at no one. He doesn’t even seem to notice when fellow draftee Mikal Bridges tries to offer congratulations. Finally he arrives in a quiet corner, away from the commotion. “Thanks for believing in me, Coach,” he says into the phone. A few moments later he beams and says, “I wish I could fly out there tonight!”

He moves from the hallway to the press room podium, joy and disappointment etched on his face in equal measure. “How I envisioned this night,” he says, “I didn’t envision it like this. My whole life I envisioned things happening different than how they happened.” He says now what he’s said before—he wanted to go as high as possible—but also that the organization ultimately mattered more than the number. The Nuggets are a fringe playoff team. If he needs more time to get healthy, they can give him that. And regardless of when he plays, he’ll be surrounded by good talent and coaching, an organization with a solid structure in place.

Later, more than halfway across the country, the Nuggets front office tells their side of the story. Team governor Josh Kroenke says that he flew into Denver for a meeting the morning of the draft, when his staff explained that Porter might be available for them at no. 14.

“Seriously?” Kroenke said.

The Nuggets called Porter for the first time later that day, telling him that they expected he’d be off the board by the time they picked, but that if he remained available, they had interest. After choosing him, team president Tim Connelly said, “We are going to be extremely patient. We’re going to take the long view for everything we do with him.”

He holds potential as an All-Star and as a bust, as someone who could eclipse the careers of every player selected before him and someone who could wash out of the league before making much of an impact at all. He insists that over the long term, his health will not be a concern. If he’s wrong, the Nuggets will have wasted a pick that typically yields little return anyway. If he’s right, he may end up one of the great steals of any draft.

For now, back in the underbelly of the Barclays Center, he wanders out of the press room and back to the hall. This was a night of dreams both thwarted and realized, each in a span of hours. It was a night he’ll remember in full color, regardless of what happens next. He walks slowly back through the hallway and onto the main floor, to face more cameras and shake more hands, before dinner and bed and a plane to Denver to meet the people who wanted him, the people who see in him the talent and potential that Porter sees in himself.