There’s still a lot at stake on the last day of the NBA regular season, but the front-runners for this year’s end-of-season awards are all pretty clear. Still, our staff makes it official by turning in ballots for all six major trophies.

Sixth Man of the Year

Danny Chau: Lou Williams. One of the most reliable pick-and-roll scorers of his generation just had his best season yet, with career-high averages all over the board—and it all came off the bench. A few months ago, there were legitimate discussions about whether Williams deserved to be an All-Star. That doesn’t often happen with a reserve. He will take home his second Sixth Man of the Year award soon. There is no close second. (We can save the discussion about Sweet Lou’s defense for another time; let’s circle back in 15 years.)

Jason Concepcion: Williams. The world is a complicated place, so let’s be grateful for easy decisions. Williams should be your Sixth Man of the Year, placing him alongside Jamal Crawford, Detlef Schrempf, Ricky Pierce, and Kevin McHale as a rare repeat winner of the award. Lou is averaging 22.6 points and 5.3 assists (both career highs); he’s the first player ever to lead his team in scoring off the bench; and he’s the highest-scoring bench player in 29 years. The Clippers—devoid of star power after the offseason loss of Chris Paul and the midseason trade of Blake “Clipper for Life” Griffin and hobbled by a panoply of injuries—remained in the playoff hunt largely because Lou regularly turned into molten lava. Now, sure, the Clips did actually miss the playoffs. But who cares? Certainly not Lou, who said, “Um, yes,” when asked whether he should win the award. Easy peasy.

John Gonzalez: Williams. He’s started 19 games, but he’s been the quintessential sixth man for much of the season—which is pretty much how his entire career has gone. This is his 13th season in the NBA (which I still can’t believe; I am old and it gives me the sads). The most games he’s ever started in a single season was 38, in 2009-10 with the Sixers. He’s been a sixth man his whole life, and this season has been one of his best performances in the role he was born to play.

Williams is a huge reason the Clippers managed to stay in the Western Conference playoff picture as long as they did. Look at the on/off numbers for Sweet Lou and the Clippers’ offense. They’re a considerably better scoring unit with him on the floor. He earned every bit of that new contract this year.

Kevin O’Connor: Williams. Shout-out to Fred VanVleet for leading the Raptors bench, and to Eric Gordon for another spectacular scoring season, but this is Lou Williams’s award. The Clippers could’ve sunk into obscurity midseason with their injuries and the trade of Griffin, but Williams kept them afloat. Williams made a legitimate All-Star push and ended up averaging 22.6 points. The Clippers were 8.6 points better per 100 possessions with him on the floor than they were without him. If it weren’t for Lou Will, they certainly wouldn’t have made as strong of a playoff push.

Haley O’Shaughnessy: Williams. Name another bench player who was also an All-Star candidate. Williams was whatever the Clippers needed him to be this season—which, by the end, was nearly everything. He led the second unit, he started, and he filled in when Injury SZN hit L.A.’s backcourt. Crawford is the only player since 1992 to win the Sixth Man more than once. Williams won the award in 2014-15—and we all know how much Lou Will loves having two of something.

Jonathan Tjarks: Eric Gordon. Williams will probably win the award, but Gordon has been an underrated component of one of the best offenses of all time. He’s a volume 3-point-shooting machine who can create his own shot off the dribble, and he’s stepped in for both James Harden and Paul when they’ve been injured. Gordon is a much better defender than Williams, and his performance is integral to the Rockets’ bid to advance to the NBA Finals. There’s a reason Houston kept him over Williams last offseason. He’s a better player.

Paolo Uggetti: Without Williams, the Clippers might have been in the tank race. His 22.6 points per game (the highest of his career) were good enough to keep a team that lost Paul, traded away Griffin, and saw numerous players go on the injury list in the playoff hunt up until the last week of the season. Williams became the go-to scoring option while also averaging a career high in assists (5.3, more than two more per game than last season), and he even started 19 games when the Clippers needed him to. Williams is the classic example of what we’ve come to expect from a Sixth Man of the Year: He’s a scorer who can fill it up at will. I look forward to him becoming the next Jamal Crawford.

Justin Verrier: Most Improved Player is probably the most inconsequential honor distributed during awards season, but Sixth Man might be the most asinine. Based on voting history, the latter rewards a player who plays as often as a starter, while producing at a level that is unremarkable within the full context of the league. And lately, that player’s glaring flaw (read: defense) is what pushes him to the bench in the first place (read: Jamal Crawford).

Williams’s season presents the best argument against that thinking, given his (ostensibly) legitimate push for an All-Star bid. As a result, he’s the easy pick here. But the fact that he wasn’t voted among the 12 best players in his conference—or wasn’t even the first call-up off the cutting-room floor to replace the injured DeMarcus Cousins—and isn’t likely to receive much All-NBA consideration only proves that his impact on the league at large was moderate, at best.

LONG LIVE THE SECOND-BANANA AWARD. (But congrats, Lou.)

Results: Lou Williams (7), Eric Gordon (1)

Most Improved Player

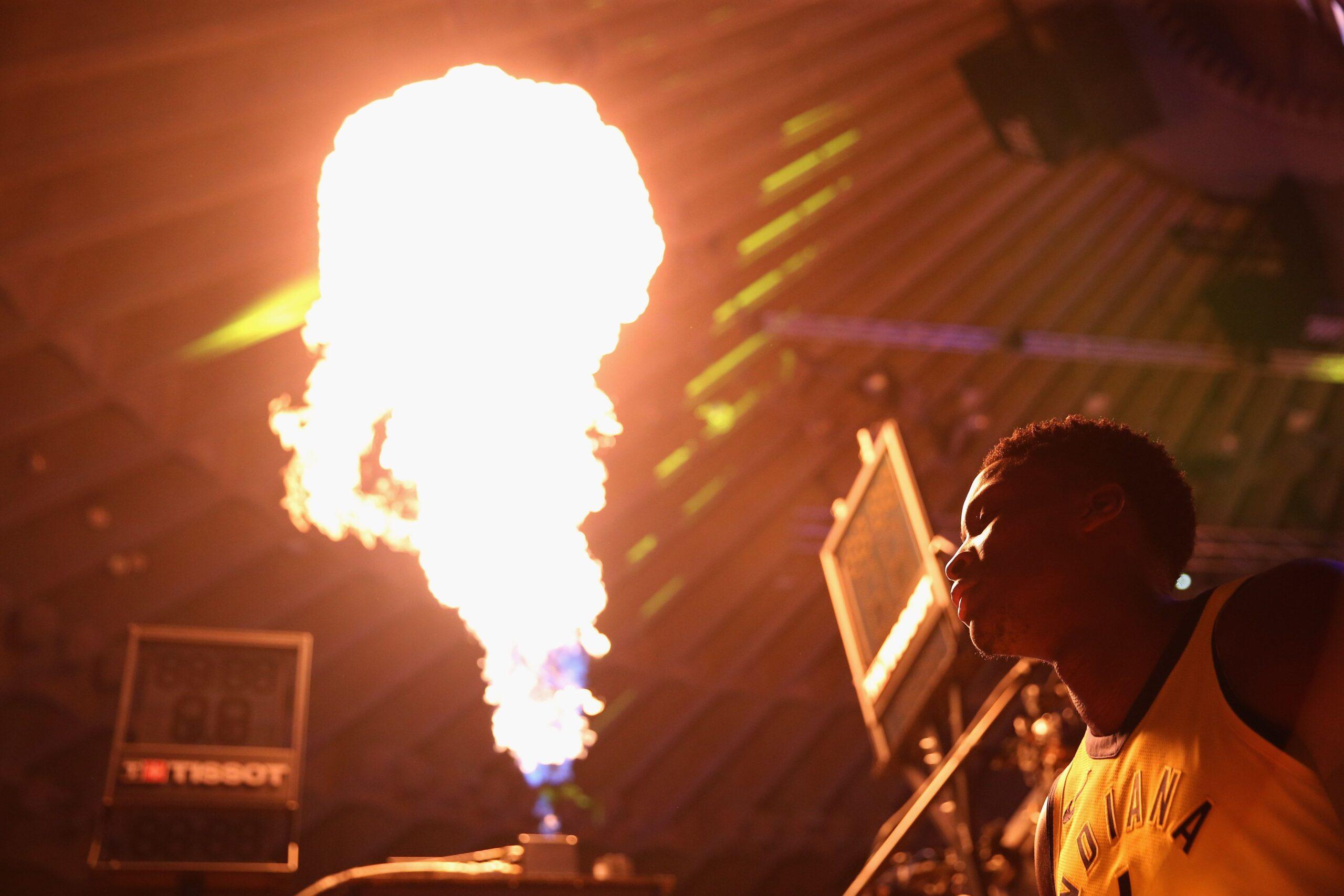

Chau: Victor Oladipo. How many alternate timelines exist in which Oladipo goes from an overwhelmed de-facto second option in the shadow of one of the greatest individual seasons in NBA history to arguably the most improved Most Improved Player in recent memory? Credit opportunity, credit the increased attention to health and conditioning, credit the natural arc of an elite athlete who is still only 25 years old. Oladipo’s model-breaking growth has allowed for a seamless transition out of the Paul George era. We’re still less than a year into the Oladipo Age, but it’s already more than anyone could have possibly predicted.

Concepcion: Oladipo. Emerging from the shadow of Russell Westbrook like the sun rising in the east, Vic Oladipo, and the Indiana Pacers, have been one of the unexpected thrills of the season. Vic was a high-volume, low-efficiency gunner his first four seasons in the league—a kind of wealthy man’s Monta Ellis, minus the “Have It All” swagger. This season, he’s looked like an integral building block plucked from a bargain bin. He is averaging career highs in points (23.1), rebounds (5.2), assists (4.3), steals (2.4, which leads the league), field goal percentage (47.7), and 3-point percentage (37.1), and he’s second in the NBA in individual defensive rating!

Also:

Gonzalez: Oladipo. He went from good to great when no one expected it, and he’s the main reason why the Pacers have had such a delightful and surprising season. He recently told me that those first few seasons in Orlando and Oklahoma City were humbling for lots of reasons—from injuries, to not playing the way he wanted, to not feeling like he got the kind of support that he needed—which is why he’s enjoying his time in Indiana. I don’t know whether anyone, the Pacers included, thought he’d reach this level when the George trade went down, but it’s worked out awfully well for Indiana and Oladipo.

O’Connor: Oladipo. State and local elections often have uncontested races in which only one candidate runs for a position, so when you get into the voting booth, there’s just one name with a bubble and a place to write in other candidates (like Elon Musk or Mickey Mouse). That’s pretty much how I’m viewing the Most Improved Player of the Year race. There’s Victor Oladipo and his bubble, then a line. Write in a name if you’d like, but Oladipo went from an overpaid rotation player to a potential All-NBA player. This season, there is no other real competitor.

O’Shaughnessy: Oladipo. It took three regular-season games with the Pacers for Oladipo to score more points than he did in last year’s first-round series against the Rockets (in half the minutes). Dipo’s stats were expected to jump—he was leaving the side of a player who had set a record for usage rate for a roster with Myles Turner as its best player. Oladipo’s stat line did, of course, skyrocket, but so did Indiana’s ceiling because of it. He transformed his body, refined his skill set, and turned the Pacers into the Jazz of the East.

Tjarks: Oladipo. I love being a contrarian as much as anyone, but it’s hard to make the case for anyone else. Oladipo went from a forgotten second wheel that Oklahoma City couldn’t wait to unload to a franchise player in Indiana. His usage rate skyrocketed from around average for a starter (21.4) to one of the highest in the league (30.1). Just being able to play 75 games with that type of offensive workload is impressive, much less significantly improve his field goal percentage and assist-to-turnover ratio in the process.

Uggetti: Oladipo. I spent way too long trying to think of who I could make a case for besides Oladipo. Nope. It’s still Oladipo. The Pacers guard has gone from league-average starter to All-Star in one season. And though I think all he needed was the right system to take advantage of his skill set, you can’t hold that against him. The improvement, no matter what spurred it, has been remarkable.

Verrier: Oladipo’s transformation in Indiana was the NBA equivalent of a “hunky makeover” on Oprah: After living in the gym over the offseason, the former no. 2 overall pick shape-shifted from a tertiary offensive option best known for his occasionally impactful defense and his dunk-contest flub to one of the best guards in the NBA and the cornerstone of a suddenly feisty playoff team. That’ll do.

Results: Victor Oladipo (8)

Coach of the Year

Chau: Dwane Casey. It’s a crowded field with so many deserving candidates, but I remain impressed by Casey’s early-season stratagem that he’s remained committed to for the entire season. Toronto has managed to achieve something special en route to its undisputed 1-seed in the Eastern Conference: The team has cultivated an underground youth movement that isn’t quite as conspicuous as what’s happening in Boston or Philadelphia, but nonetheless is a pivotal part of its success. The Raptors have the best bench in the league, almost completely made up of second- and third-year players who collectively embraced their roles as high-energy spark plugs on both ends of the floor: a lot of drive-and-kick basketball, a lot of roving defense from every single position. More than any one schematic change, it was a change of philosophy that completely altered the trajectory of the Raptors this season. There were so many opportunities for Casey to flinch and bring things back to how things were. He never did. And so the Raptors could be looking at their first 60-win season in franchise history.

Concepcion: Brad Stevens. Coaching, as ever and until further notice, is best measured indirectly—how many games should a team win versus how many they actually win. Does a team underachieve or overachieve? There’s no perfect way to measure that. But the conundrum does become easier to crack when a team lacks talent on the floor. Somewhere in that difference between expectation and result, like a ghost in the machine, is the coach.

Now consider the Celtics.

Star free agent Gordon Hayward’s season ended in the first quarter of his first game. Defensive catalyst and All-Zero Fucks Given First Team member Marcus Smart has missed more than a third of the season with hand and thumb injuries. German backup big and crucial lineup cog Daniel Theis had season-ending knee surgery. The 24 points per game of superstar flat-earther Kyrie Irving—whose acquisition capped Danny Ainge’s offseason run for the ages—are off the board after only 60 regular-season games. And yet the Celtics sit at 54-27 with one game to play and are the second seed in what is (considering the past 15 or so years) a relatively robust Eastern Conference. Stevens (and, as a Knicks fan, it pains me to write this) is an elite coach and the 2017-18 Coach of the Year.

Gonzalez: Casey. Before the season, I just didn’t understand why the Raptors were bringing back essentially the same group again. It looked like they were placing another big bet on the same approach that failed in the playoffs over and over. At the very least, I thought they should shake it up a little and replace Casey. And then the season began and we saw the Raptors playing a different style than they had in the past. They went from 22nd in 3-point attempts per game last season to third this season. That’s a massive year-over-year jump. They also increased their pace, leaping from 22nd to 13th over the same span. And through it all, they’ve been one of the NBA’s most consistent teams this season. All of that is a credit to Casey. He did something rare in professional sports: He overhauled an approach that was working for him and went with something even better.

O’Connor: Stevens. The case is strong for many coaches, especially Jazz coach Quin Snyder, who, for the second season in a row, has gone overlooked. But the Celtics lost Hayward five minutes into the season and Kyrie Irving played only 60 games. Key defenders—Smart and Theis—suffered injuries that ended their regular season. Al Horford and Marcus Morris both missed extensive time. Yet the Celtics will finish with the fourth-best record and sixth-best net rating in the NBA, and a lot of the credit should go to the coaching staff. Stevens maximized and enhanced his injury-riddled roster with masterful play calling, role distribution, rotations, and leadership.

O’Shaughnessy: Casey. A handful of praiseworthy coaches have fallen into Chopped territory this season—they took the random roster elements they were given and turned it into something that worked beautifully. Stevens, Quin Snyder, Gregg Popovich, and even Brett Brown and Nate McMillan fall under that category. Stevens and Snyder could easily take the award, but Casey is my winner because what he was able to not only maximize his talent, but did so by tweaking his own coaching system. The Raptors went from outdated and stagnant to modern, moving the ball with the best of them, and shooting more 3s—all while playing top-five defense and grooming a deep bench.

Tjarks: Quin Snyder built such a strong enough foundation in Utah over the past few years that he was able to plug a rookie (Donovan Mitchell) in place of Hayward and stay above water. Maybe even more impressive is how he was able to clinch a playoff spot out West despite Rudy Gobert playing in what will likely end up being 56 games. He would deserve to win COY just because of the way the Jazz have exceeded expectations this season, but this award has been a few years in the making for Snyder, who has quietly turned Utah into one of the most consistent franchises in the NBA.

Uggetti: Snyder. Just making the playoffs after the Jazz lost Hayward this summer is enough to nominate Snyder for this award. Potentially landing the 3-seed in the Western Conference with a rookie carrying the team through injuries should be enough to tip the votes in his favor. For all the hoopla around the wizardry of Stevens, Snyder’s dark magic has made as much of an impact on this year’s playoff picture. He’s turned a roster without a single All-Star into a team no one wants to face in the playoffs.

Verrier: Gregg Popovich. Casey, with his Raptors at the top of the East standings and on the cusp of entering the 60-win club, can make the loudest case, but I can’t bring myself to reward the seventh-year Raptors coach for a retooled crop of role players (that’s Masai Ujiri’s job) and finally catching up with the modern game in 2018. And while Stevens and Snyder have both had their share of adversity, let us cut to Pop as he asks the young gurus to hold his vat of wine. As his MVP candidate’s camp lobs shitstorms his way every couple of days, Popovich has made a playoff team (yet again) out of LaMarcus Aldridge, some players so obscure even deep-cut NBA fans struggle to place them, and a few alumni from the glory days. For all the talk about the Raptors’ reinvention, the Spurs’ offense looks closer to the one it ran during its first title season in 1999, not the most recent one in 2014—and they’ve still somehow managed to cobble together a point differential on par with the Celtics. Could another coach win even 40 games with this roster? You can’t argue that Pop coaches the best team, but he has, once again, been the best coach.

Results: Dwane Casey (3), Quin Snyder (2), Brad Stevens (2), Gregg Popovich (1)

Defensive Player of the Year

Chau: Rudy Gobert. If I could give the award to both Gobert and Joel Embiid, I’d be happy—two giants thriving in an age of small ball, creating impenetrable fortresses around the rim by sheer force of presence. Gobert gets the edge when you factor in how mediocre the Jazz were in his absence (11-15 overall). His return ignited just about everything for the team. There was no player who created more of a difference on the defensive end than he did, no matter how many games played.

Concepcion: Joel Embiid. Gobert is, all things considered, the more robust and seasoned defender. But Joel, even with the recent facial fracture, has played more overall minutes and is just more fun to talk about because he’s apt to do shit like Insta story his trip to the ER and howl futilely over Twitter at Rihanna. I acknowledge that this is a liberal reading of the requirements for this award. I don’t care; this is a thought experiment and I’m going with the more interesting player.

Gonzalez: Gobert. He missed 26 games, which some voters might knock him for—because some voters forget they have two eyeballs and eyeballs are useful for situations like identifying who’s good at defense and who other players are afraid to challenge. There’s a reason the best defensive rating among five-man lineups that have played more than 150 minutes together is anchored by Gobert. That man is an absolute rim-protecting monster. Challenge him at your peril.

O’Connor: If Gobert were a Mortal Kombat final boss, he’d be Shao Kahn—a nearly unbeatable force who looks the part. Gobert blends his ludicrous 7-foot-9 wingspan with ludicrous hustle with ludicrous instincts as the NBA’s most feared rim protector. The Jazz have a good defense even without Gobert, but with him, they’re the best (97.5 defensive rating with Gobert on the floor). The only argument against Gobert is games played, but unfortunately Embiid also has missed time, and Anthony Davis hasn’t quite matched Gobert’s impact since he needs to carry such a heavy offensive load. No other candidates have come close to making the same impact.

O’Shaughnessy: Gobert. The fact that Gobert missed 26 games will be used against him, but there’s a glass-half-full look at that argument. During Gobert’s 11-game absence in November, Utah’s defense was middle-of-the-pack. And in the 15 games he missed in December and January, the Jazz were the fourth-worst defense in the NBA, allowing 111.8 points per 100 possessions. Compare that to what Utah’s done since, with Gobert back in the paint, his 9-foot-7 standing reach stretched out: Utah is holding opponents to 97.4 points per 100 possessions, the lowest in the league.

Tjarks: Gobert. With Kawhi Leonard missing most of the season and Draymond Green not playing at quite his usual level because of injury or just general indifference to the regular season, the DPOY is now Gobert’s to lose. Even though he’ll likely play in only 56 games, he’s been such a dominant force in his time on the floor that it’s hard to give it to anyone else. The question, though, is whether his paint dominance will translate to the playoffs, as the Warriors had no trouble dragging him out to the perimeter and dicing him up last season.

Uggetti: Gobert. How do you play fewer than 60 games in a season and still become the clear favorite for this award? By being Rudy Gobert. The Jazz center’s Mr. Fantastic–like length and energy have created a force field around the rim for opposing offenses. We’re still trying to quantify defensive impact, but the numbers we do have available present a pretty good case: The Jazz are nearly eight points worse per 100 possessions on defense when Gobert is off the court.

Verrier: Gobert. The math is on his side. In addition to his elite rim protection numbers, the gap between Gobert’s league-leading Defensive Real Plus-Minus and the rest of the regular contributors has been significant. And while the Jazz’s record this season with him is roughly equivalent to the season-long success of the Warriors, their record without him is roughly equivalent to the Lakers. Gobert’s defense is the identity for his team, in the same way Harden’s is for his. His reward for doing so should be just as great.

Results: Rudy Gobert (7), Joel Embiid (1)

Rookie of the Year

Chau: Ben Simmons. Perhaps one day the league will change qualifications for redshirted players, but it hasn’t yet. In any case, Simmons has my vote. The breadth of his impact on both ends of the floor is almost unquantifiable. Donovan Mitchell may very well go on to have the better career, but few players—rookie or not —have captured the intrigue of this season as well as Simmons.

Concepcion: Simmons. As a 6-foot-10, all-seeing-eye point guard repped by Rich Paul, Simmons has long seemed the player to whom LeBron James would pass the metaphorical torch. For branding purposes, at least. Last week, Simmons went at James like he was trying to rip the torch from his hands. He had seven points, eight rebounds, and five assists in the first quarter of a game in which only LeBron’s sheer greatness (44 points, 11 rebounds, 11 assists, one block, and two steals) managed to save a close loss from the jaws of a blowout defeat. Simmons ended with 27 points, 15 rebounds, and 13 assists.

I have no idea what his ceiling is, but “Future MVP” certainly seems to be resting snuggly beneath it. Everyone on earth knows that Simmons doesn’t have a jumper. And everyone on earth has been waiting for that to hurt him. Yet it keeps kind of not hurting him. Perhaps that will change in the playoffs; perhaps not. Simmons’s ability to zip passes along invisible lines folded inside regular space is the closest thing we have to teleportation. When he’s on the ball in the open floor going through reads, he’s like a human When You See It meme. He’s also the Rookie of the Year.

Gonzalez: Simmons. Give that man the hardware because he’s earned it (and also because Embiid got robbed last year). He’s fourth in the league in assists per game, and among rookies, he’s first in rebounds and steals per game, third in scoring, and ourth in blocks. That has helped Simmons amass the second-most triple-doubles as a rookie in NBA history. Only Oscar Robertson had more. He also passed Robertson for the longest win streak (14 games) while averaging a triple-double, according to Elias Sports Bureau. And he’s doing it all while supposedly shooting with the wrong hand. (At this point, I hope he keeps shooting with the wrong hand just to spite KOC.)

As Simmons said recently, he’s “doing things that haven’t been done in a while.” Man, was he right about that. And man, is he fun to watch.

O’Connor: Simmons is only 21 years old and he’s already one of the NBA’s 15-to-20 best players. The case for Donovan Mitchell is intriguing, and he was a better rookie than even the most optimistic evaluators could’ve expected. But Simmons said it best on Tuesday, after Mitchell wore a sweatshirt poking fun at the rookie race: “If his argument is that I’m not a rookie, if that’s the only argument he has, I’m in pretty good shape then.”

O’Shaughnessy: Simmons. This is a humbling submission for me. I have been making the case for Mitchell all the way up until the Sixers’ recent 15-game win streak. But there’s no option but to concede when a rookie transcends an award made for rookies. Simmons, like his teammate Joel Embiid last season, is not a future star or one in the making. He’s already there.

Tjarks: Simmons. Mitchell has been incredible, but this award has been Simmons’s to lose since opening night. Simmons is built like a tank and he dominates games in ways no rookie, especially one who refuses to shoot jumpers, should be able to. Everyone knew about his ability to pass and get to the rim—the most impressive area of growth for Simmons since his days at LSU is just how engaged defensively he has been.

Uggetti: Simmons. Both Simmons and Mitchell are already unguardable, which shouldn’t be possible as rookies. But the difference between them for this award isn’t as close as you may think. Simmons’s impact has been more widespread. He has scored in double digits in all but eight games this season, but the Sixers are 7-1 in those precious few games in the single digits, mostly because of his ability to affect his team’s performance in other ways. Simmons is confounding for defenses to solve. He may not be able to shoot, but his back-to-the-basket game, at point guard, is almost perfectly engineered to cover up his biggest flaw. Mitchell has been transcendent, but Simmons is unprecedented.

Verrier: Simmons. The case for Mitchell over Simmons was already difficult to make before my guy was getting roasted by Dictionary.com.

But the debate that’s sprung up around the rookie and the “rookie”—which, for what it’s worth, glosses over the fact that both players logged the same amount of years between high school and the NBA—is telling in one very important way: Playing the semantics card is really Mitchell’s only chance here. The Jazz guard’s first season may have made the most compelling case for the top spot in every other ROY race in the past decade, considering that his gaudy offensive stats have powered the fifth-best team in the NBA (by point differential). Unfortunately, it happened to coincide with Simmons’s first season, which has not only been one of the best, statistically, in NBA history, but has been integral—often on both sides of the ball—for the NBA’s fourth-best team by point differential.

Results: Ben Simmons (8)

Most Valuable Player

Chau: James Harden. I’ll let Kevin O’Connor let you know why. I have to save some of my words for the postseason.

Concepcion: James Harden. Best player on the best team—the tried and true measure of the league’s most valuable player. Though anomalies arise now and again (Westbrook in 2017, Karl Malone in 1997 and ’99) that formula largely holds true. It certainly should this year.

Gonzalez:

O’Connor: Harden.

O’Shaughnessy: Harden. This NBA season produced many fun MVP candidates to consider, but they were all dark horses in comparison to Harden. The Beard shouldn’t win because “it’s his turn.” He should win because it’s his best season yet. He’s cornered the market on every type of offense, whether it be isolation, drawing fouls, stepback 3s, or assists. Efficiency is the NBA’s favorite buzzword, and Harden is the poster child.

Tjarks: Harden. As his old teammate Kevin Durant said a few weeks ago, it’s Harden’s time. The Rockets have been the story of the regular season, and he’s the alpha and omega of everything they do. There was some concern about whether adding Paul would diminish Harden’s role, but Harden’s gravity is so great that Paul immediately accepted a smaller role in his orbit. We’re seeing a peak James Harden season and it deserves to be acknowledged, regardless of what happens in the playoffs.

Uggetti: Harden. Talladega Nights taught us that second place is first loser. But Harden, the runner-up to Steph Curry three years ago and to Westbrook last year, has springboarded into the clear-cut winner this year (and maybe even the winner last year with the benefit of hindsight). What a come up for the Beard.

Verrier: Harden. It feels wrong not to side with LeBron James in the midst of perhaps his best statistical season since his last MVP award, especially when he’ll likely play in all 82 games for the first (and probably last) time in his career. But you can’t ignore how putrid his team’s defense was this season, or those images of him standing idly by as opponents rode roughshod on the Cavs during one of the biggest implosions in recent memory. And while James’s offensive contributions this season place him on the fringes of history (his 28.6 PER, as calculated by Basketball-Reference, would rank 43rd overall since 1951-52), Harden is already in rarefied air: Only 20 players have ever accumulated a PER of 30 or more; Harden (if we give his 29.8 a slight nudge) would be 21.

Results: James Harden (8)