Think, for a moment, about the worst extended stretches for any team in NBA history. The Trust the Process 76ers probably come to mind. Several generations of Clippers and Timberwolves. An expansion team or two. The post–Michael Jordan Bulls.

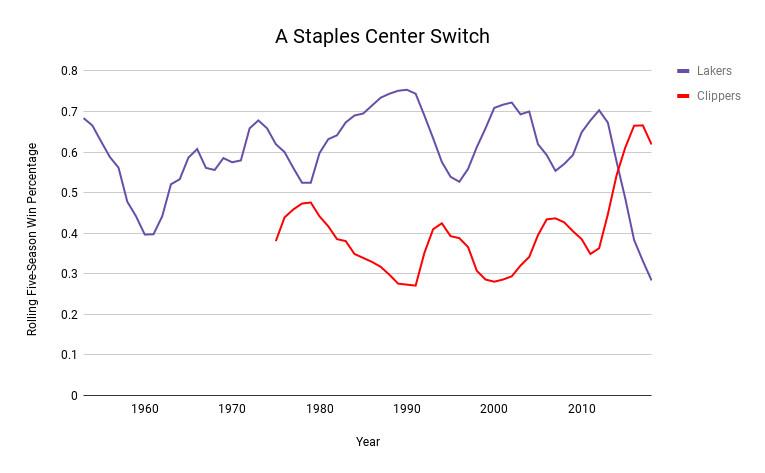

Odds are that the Lakers never appear on that mental list. And why would they? The franchise has been the most consistently great in NBA history; last September, the best example Shea Serrano could find of a “regular Lakers team” hidden among the various dynastic runs still won 53 games and earned a top-four playoff seed. The Lakers are the Logo, Magic steering Showtime, Kobe and Shaq alley-ooping Portland into the earth’s core. But lately, they have not only not contended for a 17th title, but have been downright bad; really bad; historically, consistently bad. The modern incarnation of the Lakers — who haven’t won more than 27 games in a season since 2012–13 and are currently tied for last place in the Western Conference — belong among all the tragic teams listed above.

To quantify just how bad, we can compare the Lakers’ record since they started losing — a span of five seasons now — with all other cumulative five-season records throughout NBA history. There are more than 1,300 of them, and by this simple measure, the worst such stretch in NBA history belongs to the then–Vancouver Grizzlies, who in their first five seasons of existence won just 20.6 percent of their games, the equivalent of posting a 17-65 record for five consecutive years.

At their current pace this season, the Lakers would finish their five-season run from 2013–14 through 2017–18 with the 24th-worst winning percentage in the 1,300-plus sample. Take out overlaps — for instance, counting only one of the 1996 to 2000 Grizzlies and 1997 to 2001 Grizzlies, who possess the bottom two spots on the list — and the Lakers would fall to 12th-worst. Here’s the full list of teams that have won less than 30 percent of their games over a five-season span (with overlaps removed and the Lakers’ numbers projecting that they will continue to win at their current rate for the rest of this season).

Worst Five-Season Stretches in NBA History

The first takeaway is how historically sad most of the franchises keeping the Lakers company are. L.A. is an outlier: Before this recent downturn, the Lakers hadn’t dipped below .500 over any five-season span since 1958 to 1962 — a period that began with the team still in Minnesota and ended with Jerry West’s rookie year. Now, though, they are not only crashing through the franchise’s previous floor, but also approximating the Clippers’ lowest points.

The macro narrative surrounding the team hasn’t regularly reflected this reality, though, and each season has featured either an easy excuse for the stumbling or a diverted focus away from the frightful present to the team’s glorious past and hopeful future. The 2013–14 and 2014–15 seasons were about the post–Dwight Howard detox and Kobe Bryant’s recovery from injury. The next season was Bryant’s ludicrous last. Last year was Luke Walton and fun and Magic’s management coup, and the first group of youngsters to lead the Lakers in decades. And this season is all about the years to come: Lonzo and Kuzmania and House Hunters with LeBron.

But in the vein of future projection, the second takeaway from the list of teams with the worst five-season stretches is how slowly most of those franchises recovered from their down years. The precedent isn’t promising: Besides the early-aughts Grizzlies, who were gradually building as an expansion team, every team on the list took years — in most cases, a half-decade or more — to reach 50 wins after their original half-decade of failure. Teams like the Timberwolves, Kings, and Wizards still haven’t done so in the 2010s.

Of course, the Lakers possess unique advantages among teams on this list. Besides the post-Jordan Bulls, no other prestigious big-city team appears — no, not even the Knicks — and because of both their franchise cachet and financial flexibility, the Lakers could sign LeBron James and Paul George as free agents this summer. In this scenario, the franchise would once again prosper; James is the ultimate salve. Cleveland won just 31.1 percent of its games during his four-season stint in Miami, but it immediately became the alpha in the East after James rejoined the roster.

Would James leave Cleveland for a team with minimal recent success, though? His free-agent priorities are unclear, given how little he’s spoken publicly about next summer, but the biggest clue thus far came from Maverick Carter, his business partner, who earlier this season told Rich Eisen that ability to contend would be the main factor in James’s decision. “Could he sell a few more sneakers if he was in a gigantic market like Boston, Chicago, New York, or L.A.? Maybe,” Carter said. “But not as much as if he wins. What matters the most is if he wins. When you win as an athlete that matters the most.”

James is 33 and has been playing in the NBA for 15 years, and he needs to find a means of challenging the Warriors if he wants to further his already-impressive legacy. He theoretically doesn’t want to jump-start another rebuilding effort, but that’s what L.A. represents: The Lakers have been struggling for so long that the top of next summer’s draft will be full of players who were in middle school the last time the Lakers reached the playoffs or won even 30 games.

After picking second in three consecutive drafts, the Lakers have the smudged outline of a young core in Brandon Ingram, Lonzo Ball, and fan favorite Kyle Kuzma, who joined the team this past offseason as part of a trade involving former no. 2 pick D’Angelo Russell. Nobody on the roster necessarily projects as a future no. 1 option, though, and they don’t own their first-round pick in next summer’s draft. (The Lakers could have surrendered that pick — which was part of 2012’s Steve Nash trade — as long ago as 2015, but they’ve been so lousy over the past few seasons that the pick’s top-five and top-three protections went into effect for the 2015, 2016, and 2017 drafts. It is unprotected in 2018.)

L.A.’s rebuild is far more reliant on prospective imports than, say, Philadelphia’s, which is more self-sustained and assumes stardom from the Sixers’ actual draftees. Philly’s Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons could headline a championship lineup, but in all likelihood, the best player on L.A.’s next finalist isn’t already on the roster. If James doesn’t choose the Lakers, they could easily go the same way as the other biggest five-season losers and take many more years to return to contention. George alone, for instance, doesn’t much move the needle; as a lone star in his last two seasons in Indiana, he piloted two 7-seeds and didn’t win a playoff series in the weaker Eastern Conference.

History indicates that the franchise is in a precarious position, despite what the more optimistic narrative surrounding the team might suggest. Los Angeles exceptionalism might woo James and reestablish Staples as a championship destination, but the Lakers’ road back could be a lot longer and bumpier than people seem to think.