I admired Mac for so many reasons—his artistry, his humor, his vulnerability. But his mastery of convincing me to drop what I was doing and come hang was unparalleled.

Just come over.

Move your flight.

I’ll pick you up.

Just move here.

His efforts always brought a smile to my face, even when coming there was wildly inconvenient or geographically impossible. And more often than not, I went to go find him—like so many of his friends did—because he was fun, he was kind, and the kid loved to chat. The night of February 18 of this year was a perfect example.

Mac had me cornered because he knew all of my L.A. vitals during that trip: where I was staying, what time my flight left in the morning, and that his house was closer to the airport than my hotel.

I’d just finished watching the NBA All-Star Game at a bar when I got a text from Mac. I was near my hotel, I’d only seen him once during my seven-day stretch in town, and I missed him. Our texts were frequent and calls scattered, but in-person visits had become rare since he’d moved back to L.A. So, per usual, I packed my bags, exited my hotel room, and took a car to Studio City, at midnight.

I arrived and he was extremely happy to see me, more than usual. With him in his standard home attire of shorts and a long-sleeved shirt, socks, and flip-flops, we sat on his couch. I never knew who was going to be over, but this evening his house was oddly quiet, even for a Sunday night. After a few minutes of catching up, he changed the subject.

“So … Karl-Anthony Towns and five of his friends are on their way over. Like I said, I’m so glad you’re here.”

He’d presented me with a lifetime of surprises in the years we’d been friends, but this was easily the most left field. Or so I thought. Extremely confused, I asked him to explain everything about how he knew Towns, sparing no detail, which took a lot less time than I expected.

The story was simple. Karl-Anthony Towns, according to Mac on his couch, was one of the biggest Mac Miller fans that walked the earth. And this wasn’t a new development; it went years-deep, and something Mac became familiar with when Towns was a college standout at the University of Kentucky. And this fandom, over time, blossomed into a friendship.

I was floored, but it also made sense. I knew how wide-ranging his fan base was, I’d seen the crowds at his shows. But even with this understanding, there was still a humanity-affirming absurdity to Towns’s voyage to Mac’s house, on this of all evenings. Towns, just hours earlier, was playing in the NBA All-Star Game, across town. Who didn’t love Mac?

Mac was both tickled and touched that Towns would want to see him, considering what he could be doing on such a star-studded night, Mac not thinking of himself in the moment as a studded star. But he had some unease when it came to the caravan. That’s where I came in, I figured. He wanted someone silly to help him get through what could be a potentially awkward evening.

Ten minutes after I was told of the night’s direction, Towns walked in—all seven feet of him. Behind him came a woman, and behind her a man, who, within seconds, began filming the encounter. Two other friends followed.

The camera was out and the front door wasn’t even fully closed. “Kids these days,” I thought, doing the quick math that I was almost a decade older than Karl-Anthony Towns. Mac politely asked whether they could not film in the house, and the guy apologized.

Two minutes in and Towns was visibly embarrassed. He was in the home of one of his heroes, and he’d already accumulated a strike.

I felt like I was in an alternate universe: an NBA All-Star, blushing from excitement, then apologizing in embarrassment, minutes apart, to my friend Malcolm, a rapper in flip-flops and socks.

With a huge collection of people now talking on Mac’s couch, Towns pulled out a shopping bag. He had presents for Mac. In the moment, I wouldn’t have guessed that they’d be four Minnesota Timberwolves Karl-Anthony Towns jerseys, but looking back, I’m so glad they were four Minnesota Timberwolves Karl-Anthony Towns jerseys. Two were green and two were gray, all four with the Fitbit logo on them.

Mac, pulling them out, said “I’m really getting it because I just super support Fitbit.” Towns bowled over in laughter, the way you do when you’re in the middle of a dream coming true. Towns kept laughing as Mac followed it up with “I love Fitbit, bro.”

He didn’t need me there; he had the room. And to Towns, he could do no wrong. I loved it, every second more pure than the previous.

As this was happening, I noticed the guy once filming had turned on his camera again. Mac noticed too, but he let it slide. He knew Karl wasn’t there for content; this was a big deal to him. He was having a hell of a day, after all—his first All-Star Game, followed by hanging out with his favorite rapper.

As Hour 1 turned into Hour 4, from watching TV on the couch to everyone packing in the studio as Mac played some music, I realized I wasn’t there to be comic relief. For years, I’d battled the quasi-imposter friendship syndrome that comes with becoming close to someone with fame. You love them, but you don’t want to overstep, tricking yourself that your welcome can be overstayed all while constantly wondering why in God’s name they like you. He’d made it explicitly clear that this—us—was real, but I still fought it. That night, I finally gave in. He wanted someone there to shoot looks at and to give sly smiles, because he was in the business of making memories, ones that we could talk about, forever.

As we got into the wee hours of the morning, Mac and I started playing music videos. We picked a staple clip, the Dipset freestyle on Rap City. The majority of Towns’s friends had no idea what was going on, which made Mac say, “Holy shit, I’m old.”

I could not stop laughing. Here I was, at 30, watching Mac, at 26, hang out with a bunch of 21- and 22-year-olds, witnessing him feel his age—and not hate it. In that moment, I flashed back to when I first met him, the first day he moved to New York City in 2015, when I was 28 and he was 23. It was one of the first days I ever felt old—and didn’t hate it.

That day, I met him at his apartment to interview and write about him. After the piece went up and some weeks went by, we’d both communicated to our mutual person, his sensational manager Nick, that we enjoyed hanging. And that we kind of wanted to do it again.

The next time had a very playdate-esque setup. He wanted to know about stuff to do in Brooklyn, and I welcomed the chance to be his Old Man River. Going into our first hang, I told him this meant I could never write about him again. He was fine with it. So was I. And so it began.

I’ll never let it end. Because the music and the texts and the photos and the memories can’t be taken away, even though his body is no longer with us.

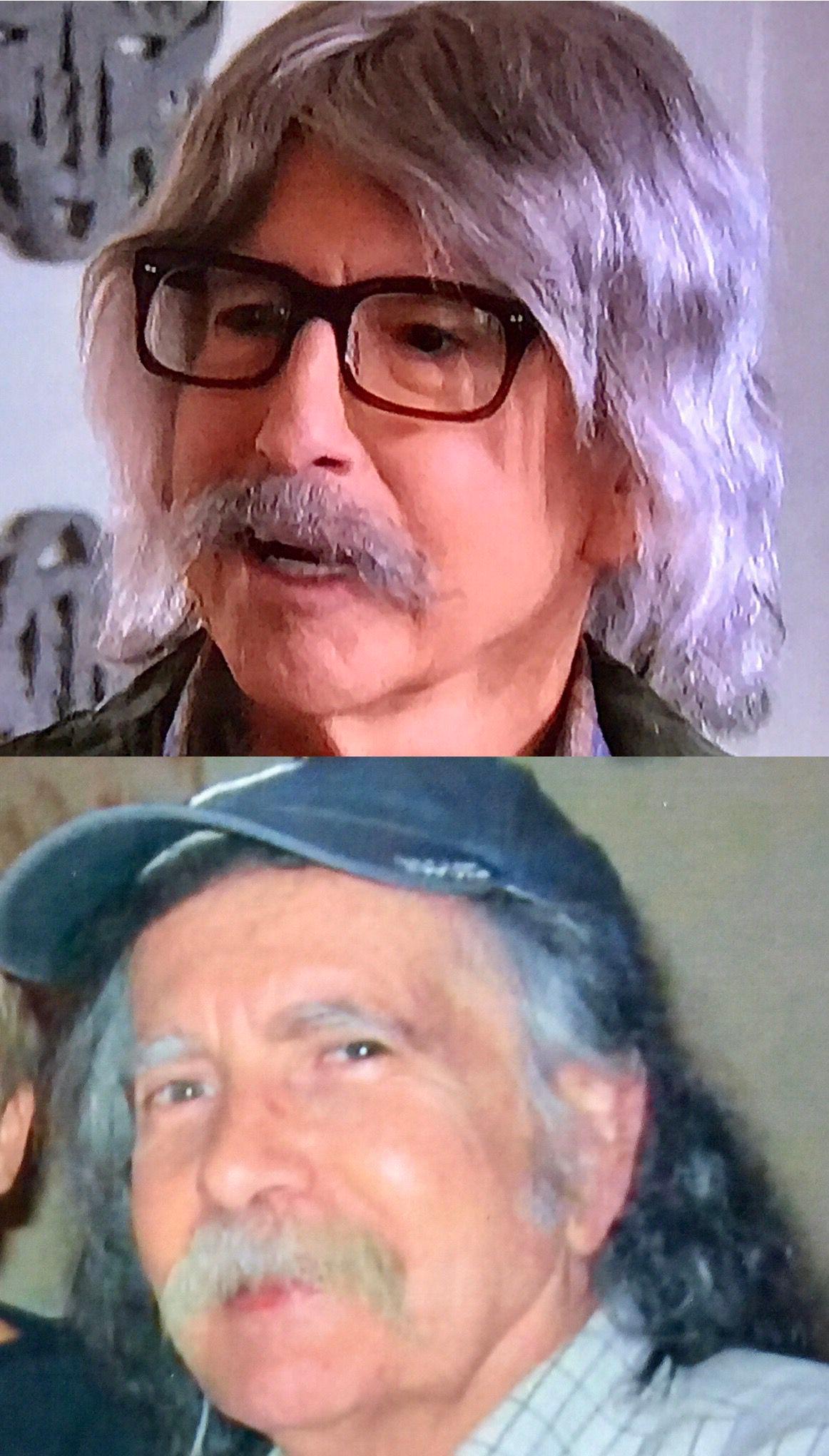

One of the things that I’m grateful for, in this hard moment, surprisingly, is that friend of Karl-Anthony Towns. I was pissed he was filming Mac in his home, but now that the video exists in the wild it gives me something to smile about when I’m at my most sad.

He made you feel like you mattered. Because you did matter to him. He loved hard and challenged you with his actions to reciprocate. And while his passion for people was infectious, making you want to match his level of care and concern, you never could—because he’d take it up another notch. Ultimately, I wish he had been more selfish, because by being so supportive of everyone he touched, he left so little time to be his own biggest cheerleader.

The cruelty of the world that takes someone as he’s finding happiness makes me question nearly everything. But the one thing about the uncertain future that I know as fact is that Malcolm will never be forgotten. Whether you knew him up close or from afar, whether you watched him in his house or on stage or heard him through headphones, he positively altered the course of too many lives to fade into the background. We will be his cheerleaders, and we will be his champions, and we will tell his story. The loss may never stop hurting. And that’s OK. Because there was simply no one quite like him.

Rembert Browne is a writer living in New York.