There are moments during High Flying Bird when it feels as if you’re listening at half-speed. It could also be that everyone is just talking really fast. In either case, closed captioning comes in handy. The players in Steven Soderbergh’s sporting melodrama—which is NOT about the NBA, although it is about “the league”—are prone to dense, expositional dispatches about stuff like race and agency, or the lost innocence of a playground game hopelessly complicated by corporate interests. That’s not a knock. I love dense, expositional dispatches and melodrama. I also love nimble, Sorkin-y dialogue. Almost as much as I love the Lord and all his black people. High Flying Bird is sort of preachy, but in an earnest and charming and artful and occasionally funny way.

High Flying, the second of Soderbergh’s iPhone movies, examines a broken capitalist system and dreams up slightly implausible ways to fix it. Chances are the NBA wouldn’t end a lockout over the prospect of pay-per-view games to 21 that they couldn’t profit from, but isn’t it fun to think so? Michael Baumann has a more considered take about the film’s proximity to reality and its preoccupations with player power, and I agree with almost all of it. I disagree strongly, however, with the idea that High Flying “includes almost no actual basketball scenes.” There are plenty of basketball scenes. Yes, there’s the one where Erick Scott (Melvin Gregg), a no. 1 draft pick in waiting, settles his differences with future teammate Jamero Umber (Justin Hurtt-Dunkley) in a pickup game. But there are so many more, most featuring Erick’s agent, Ray Burke (André Holland), who is never lost for words and just oozes been-there-before poise. He’s the movie’s primary ball handler. And its best finisher at the rim.

Let’s back up. The script was written by Tarell Alvin McCraney, the playwright behind Moonlight. The scenes in that film build more slowly and have a simmering mournfulness to them, whereas the exchanges in High Flying are more propulsive. Watching it, I was fascinated with how everything any character said sounded as deft and witty as the thing you only ever think of after the interview, the meeting, the argument. If you read reviews of the film, you’ll find people describing how the dialogue “crackles” and “pops,” and it does. Like possessions in an actual basketball game, conversations move fast and are either won or lost, rather than just, you know, had.

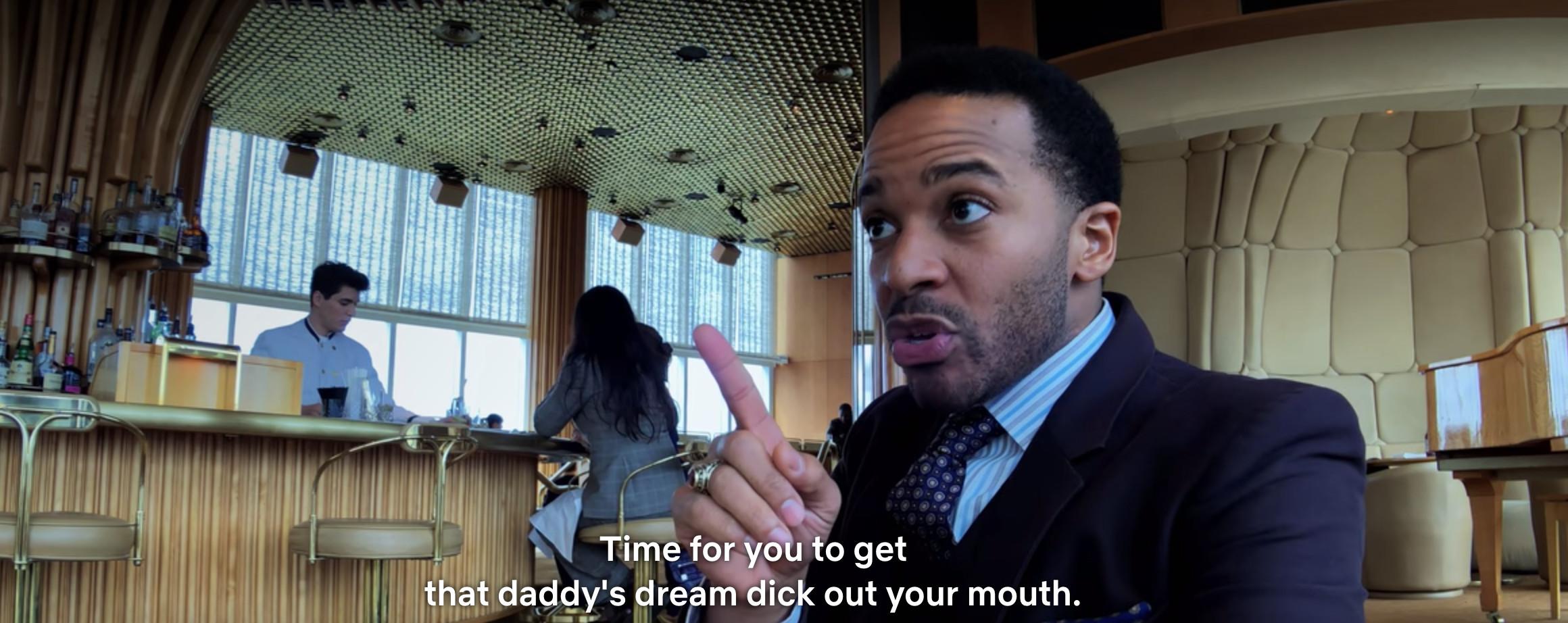

I mean, right from the beginning. High Flying opens in an upscale Manhattan restaurant—the kind of place where people have “luncheons”—with Ray ferociously scolding Erick for spending money he doesn’t have. Ray’s wisdom about financial literacy and the perils of nascent NBA stardom is suffocating; Erick can hardly get a dejected look in edgewise, much less a word. Every accusatory mention of short-term loan interest is like Erick being caught out reaching. Remember when 50-year-old Michael Jordan destroyed a teenaged O.J. Mayo at summer camp? This is like that.

Ray is on the receiving end of a schooling too. He’s 20 percent historian, 20 percent businessman, 15 percent therapist, 15 percent accountant, and 50 percent dreamer, which adds up to 120 percent of an agent. Ray’s vaguely annoyed most of the time but full of howling ambition, always working the angle on some larger picture. His scheming takes him all the way from New York to Philly in one scene to talk to Jamero’s mother, Emera (Jeryl Prescott), who … backs Ray down, hangs off the rim over him, and then pushes him into the courtside seats. She takes the meeting under the pretense of finding Jamero new representation, only to reveal herself as Jamero’s representation and question both Ray’s godliness and fortitude in the process.

Then again, it’s only supposed to seem like Ray was getting dunked on. The big con is that the whole movie is one long possession, during which Ray shows just enough of the ball, like any good ball handler would. At the end of that first scene in the restaurant, his business card is declined, and he’s so cool and composed about it that you’d swear he planned on it. When he goes into the office to learn that, along with his expense account, his salary is also frozen until the lockout ends, Ray resolves to end the work stoppage. He then goes on to succeed, letting on only as much as anyone, including the audience, needs to know at any given time. The business of the league is referred to as the “game on top of the game,” and Ray and his erstwhile assistant Sam (Zazie Beetz, who’s excellent again) run another two-man game on top of that. It’s like that old Twitter joke about Rihanna and Lupita Nyong’o: Ray scams the rich white men, and Sam is the man-management-smart best friend (who engages in a forced romance with Erick) who helps run the scams.

Like Logan Lucky or any of the Ocean’s movies, High Flying is a Soderbergh heist, except instead of a casino or a raceway, the mark is a major American sports league. Insofar that I could follow, the meeting with Emera leads to a Twitter beef, which leads to a highly visible pickup game, which leads to offers from Facebook and Netflix and eventually resolution between the players union and “the league.” All in the span of 72 hours. This leads us to the absolute best basketball scene in this movie full of basketball scenes, wherein Ray confronts his boss (Zachary Quinto) for the final time and yanks him to floor by revealing everything he accomplished, all on his own. He then drains the jumper by, we’re to assume, becoming the boss himself.

On every level, High Flying Bird is efficient; it’s a movie that takes place over one long weekend, was filmed with a budget of $2 million, and has a runtime of just 90 minutes, so it’s not the largest time suck, even if you allot for having to rewind the moves you couldn’t quite track. It’s on Netflix, so you can spread it out and pick apart its moves for as long as you want. You know, in case you want to steal them.