Four weeks ago, the Star Wars franchise was flying casual. Each of the first three entries in the rebooted tentpole property—The Force Awakens (2015), Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), and The Last Jedi (2017)—had made more than $1 billion worldwide, and presales and projections suggested that Solo: A Star Wars Story, the second Star Wars anthology movie, would break the record for a Memorial Day opening and extend Disney’s streak of lucrative Lucasfilms. With the franchise’s finances seemingly sound, Lucasfilm flexed: On the day of Solo’s debut, The Hollywood Reporter revealed plans for more spinoffs starring “a slew of characters,” including a Boba Fett flick from James Mangold and Simon Kinberg, the duo behind 2017’s Oscar-nominated Logan.

What a difference a month makes. Since late May, much of the discourse surrounding Star Wars has centered on Solo’s surprisingly soft release, which featured an $84.4 million three-day domestic take and a steep, 65 percent drop-off in its second week. Solo, which has grossed less than $200 million domestically and less than $350 million worldwide, will likely be the first film in the franchise to lose money, as compared to its budget (reportedly more than $250 million) and marketing costs. In assessing the situation, some sources have even invoked the F-word: “flop,” a foreign term where Star Wars is concerned. Star Wars fatigue, which seemed like a hypothetical prospect when we invoked it last winter, now looms as a serious threat.

Although rumors of at least nine Star Wars movies in development were circulating as recently as Sunday, it now looks like fear of diluting the franchise’s earning power will keep Lucasfilm in line. On Wednesday, Collider, citing unnamed sources, reported that the production company has “decided to put plans for more A Star Wars story spinoff movies on hold.” That may mean no Obi-Wan or Boba Fett films for the foreseeable future, and presumably no further Solo installments, although Solo himself, Alden Ehrenreich, signed on for two more films—not an unusual arrangement, even when an actor’s character is killed. On the surface, this sounds like a retrenchment that reflects some uncertainty about what the stewards of Star Wars want the series to be.

The recent torrent of cautionary news for the franchise carries real risks of overreaction, both on our part and on Lucasfilm’s. For one thing, yellow lights can turn green again: Even if these spinoff projects are frozen for now, Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy could turn off the tractor beams at any time. For another, there’s no shortage of Star Wars on the way: In addition to dependable (if predictable) crowd pleaser J.J. Abrams’s trilogy-ending Episode IX, due out next December, Last Jedi director Rian Johnson has his own trilogy in the offing, and Game of Thrones adapters David Benioff and D.B. Weiss are also developing a cinematic series of an unspecified length. At minimum, that’s six confirmed films in the pipeline, not to mention an animated TV series slated for this fall and a live-action TV show that will likely launch alongside Disney’s streaming service late next year. Spinoffs or no, it’s unlikely that Star Wars will experience any extended droughts at the theater after Episode IX. The suits may be easily startled, but Star Wars will soon be back, and in greater numbers.

Along similar lines, it’s possible that Lucasfilm is fretting too much about Solo’s subpar results (by sky-high Star Wars standards). Although Solo had Memorial Day mostly to itself, the movie arrived just after two other Disney blockbusters, Avengers: Infinity War and Deadpool 2. And unlike the previous Disney Star Wars movies, it came out in May instead of December, which meant a mere five-and-a-half-month gap between Star Wars releases. A belated and abridged marketing campaign, which unveiled the first trailer in February, added to the troubles, failing to counteract the bad buzz built up from a midproduction director change and exaggerated rumors about Ehrenreich’s portrayal of the iconic character. Furthermore, the movie’s premise made it seem somewhat extraneous: Although Han Solo was the series’s most beloved lead, The Force Awakens killed him, and the prospect of an origin story for a character whose murky past was part of his appeal held only limited interest. According to even more recent reports than Collider’s, Disney rejected a request to delay the film to December and refused to give it “preferential” marketing treatment so as not to detract from the furor over Infinity War. Solo’s struggles were, to some extent, self-created; Disney may have had a Solo problem more so than a Star Wars Story problem.

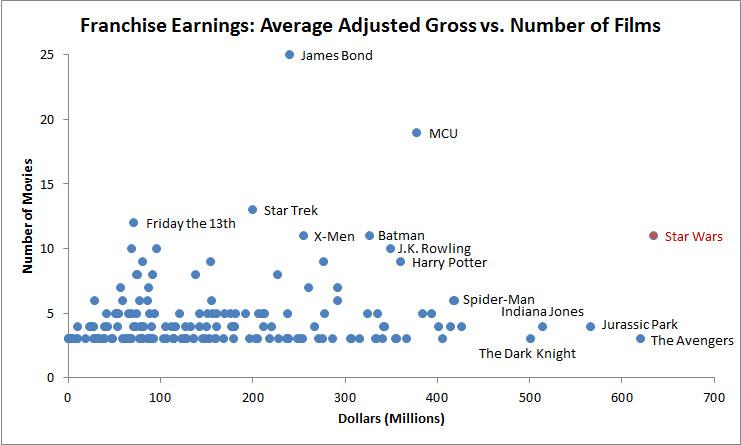

That Solo is seen as a failure highlights the lofty baselines by which we judge Star Wars. The movie worked in a number of ways, got good (but not great) reviews, was the top draw in America in consecutive weeks, and made hundreds of millions of dollars. By comparison, the franchise spinoff that unseated Solo from the top spot at the box office, Ocean’s 8, got worse reviews and will likely make less money, but is generally regarded as a greater success. That’s partly because of Ocean’s 8’s lower budget—maybe if Lucasfilm picked directors it could keep around and didn’t have to resort to repeated pricy reshoots, it wouldn’t be as big a deal that one of its movies might make “only” $400 million—but it’s also because Star Wars is a singular entity, even among major moneymakers. The plot below, based on Box Office Mojo data, shows the inflation-adjusted average earnings of every movie franchise with at least three films. The chart includes separate points for subseries within longer lineages, such as the Dark Knight trilogy and Batman’s larger, less-distinguished library, which includes Christopher Nolan’s films alongside several other entries.

Even with Solo’s not-yet-final figures dragging down the Star Wars average, the series still stands out. No other franchise matches its average revenue, and no other franchise with nearly as many movies comes close. That powerful pull has mostly been a blessing to Disney, which has already made more on Star Wars movies than it paid to purchase the franchise in 2012. But it’s been a curse in the case of Solo, whose popular perception has suffered from its inability to ascend to the same heights as previous Star Wars installments.

Past scarcity has something to do with the outlier status of Star Wars: However compelling the product, demand can’t increase as quickly as Disney has expanded supply. To at least some Star Wars fans who lived through the long lean years after Return of the Jedi, the sad spectacle of the prequels, and the decade-plus dry spell between Revenge of the Sith and The Force Awakens—and, evidently, narrowly avoided three movies about midi-chlorians—the fact the fourth Star Wars movie in three and a half years (!) is good but not great probably seems like small beans. Solo would have been the best Star Wars movie made in the 32 years before Disney rebooted the franchise; that it’s now the cause of a crisis is a sign that Star Wars fans are spoiled in the best possible sense.

It’s also a sign of how much is expected from Star Wars. In other prolific franchises, from Mission Impossible to The Fast and the Furious to James Bond, transcendence isn’t the minimum that movies have to meet to be considered successful. No other series is expected to swing for the fences every single time: In most cases, it’s OK to settle for a more modest outcome as long as it keeps the conga line moving and brings the next batter to the plate. Disney’s other massive moneymaker, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, features a couple of movies that made about the same amount of money as Solo and generated more middling reviews, which hasn’t slowed the assembly line or precluded subsequent blockbusters like Black Panther and Infinity War.

The MCU, of course, owes its source material to decades of comics that told smaller-scale stories in successive issues, and that format carried over to their on-screen adaptations. From the start, Disney established that the MCU would boast multiple movies per year and that their casts, timelines, and central conflicts wouldn’t always overlap. Star Wars, meanwhile, has always taken trilogy form and fixated on figures at the center of the fight for the galaxy, which gives it greater focus but sometimes ties its hands. The Star Wars Story entries were ostensibly attempts to escape those strictures, but Lucasfilm couldn’t completely commit to the mission.

Much as the Marvel movies also stem from a single producer at the center of the web and tend to look the same, they vary dramatically in content and tone, from the hand-to-hand combat of Captain America to the space travel of Guardians of the Galaxy to the mysticism of Doctor Strange to the lighthearted humanity of Spider-Man: Homecoming to the political perspective of Black Panther’s diverse cast and creator. The first (and, for now, last) two Star Wars spinoffs weren’t stand-alone stories at all: Rogue One connected almost seamlessly to Episode IV, and Solo revolved around original-trilogy characters. Worse, whatever uniqueness might have arisen from the individual voices chosen to helm those movies was smoothed over and ironed out by director replacements and reshoots. In choosing to tell trilogy-adjacent tales and stick strictly to house style, Lucasfilm lowered the odds of a prequel-caliber disaster but also all but ruled out any chance of making must-see material that could rival the more momentous mainline movies.

By focusing solely on non-stand-alone releases until its trilogies are in order, Lucasfilm is staging a strategic retreat and reaffirming the traditional conception of Star Wars. While it’s heartening that the company is clearly concerned about sullying the series’s reputation and extracting too much story from the stone—if only because of what it ultimately might mean for the bottom line—it’s also dismaying that the fallout from Solo is forcing big-screen Star Wars to adhere to a structure established in the ’70s, especially to the extent that Solo’s relatively low turnout can be traced to the most regressive segment of the Star Wars base. One would hope that the franchise will still allow space to experiment. But maybe that’s what the small screen is for, at least until the movies print money once more.