Best Picture

Call Me by Your Name

Darkest Hour

Dunkirk

Get Out

Lady Bird

Phantom Thread

The Post

The Shape of Water

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

I’ve had a change of heart. I spent the better part of six weeks smarmily proclaiming the power of the guilds and explaining the might of the complete voting body. Despite a vast number of new additions to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences over the past three years, I couldn’t see it. The Shape of Water, with its 13 nominations, its broad support throughout the Academy, and the respect that writer-director Guillermo del Toro draws from his peers, felt like too clear a choice. The movie is neither too controversial nor too small. (It has now earned more than $113 million worldwide.) Historically, these are the movies that win Best Picture. Think of Chicago in 2002 (13 nominations, six wins, $306 million box office) or The King’s Speech in 2010 (12 nominations, four wins, an eventual $414 million). Fine, forgettable, successful movies that we look back upon with bemusement. But then came La La Land (14 nominations, six wins, $446 million), which was all set up—narratively and empirically—for victory and glory. And we know what happened there. I’ve been calling it the Moonlight Effect for months. It’s what made me sure since last spring that Get Out would be nominated for Best Picture. But for some reason I never believed it had a chance to win. I’ve spent a month thinking about these awards, talking to people who work in the movie business and trying to understand if I’m wrong. At the zero hour, I see it differently. I think I was wrong. Get Out will win on Sunday night.

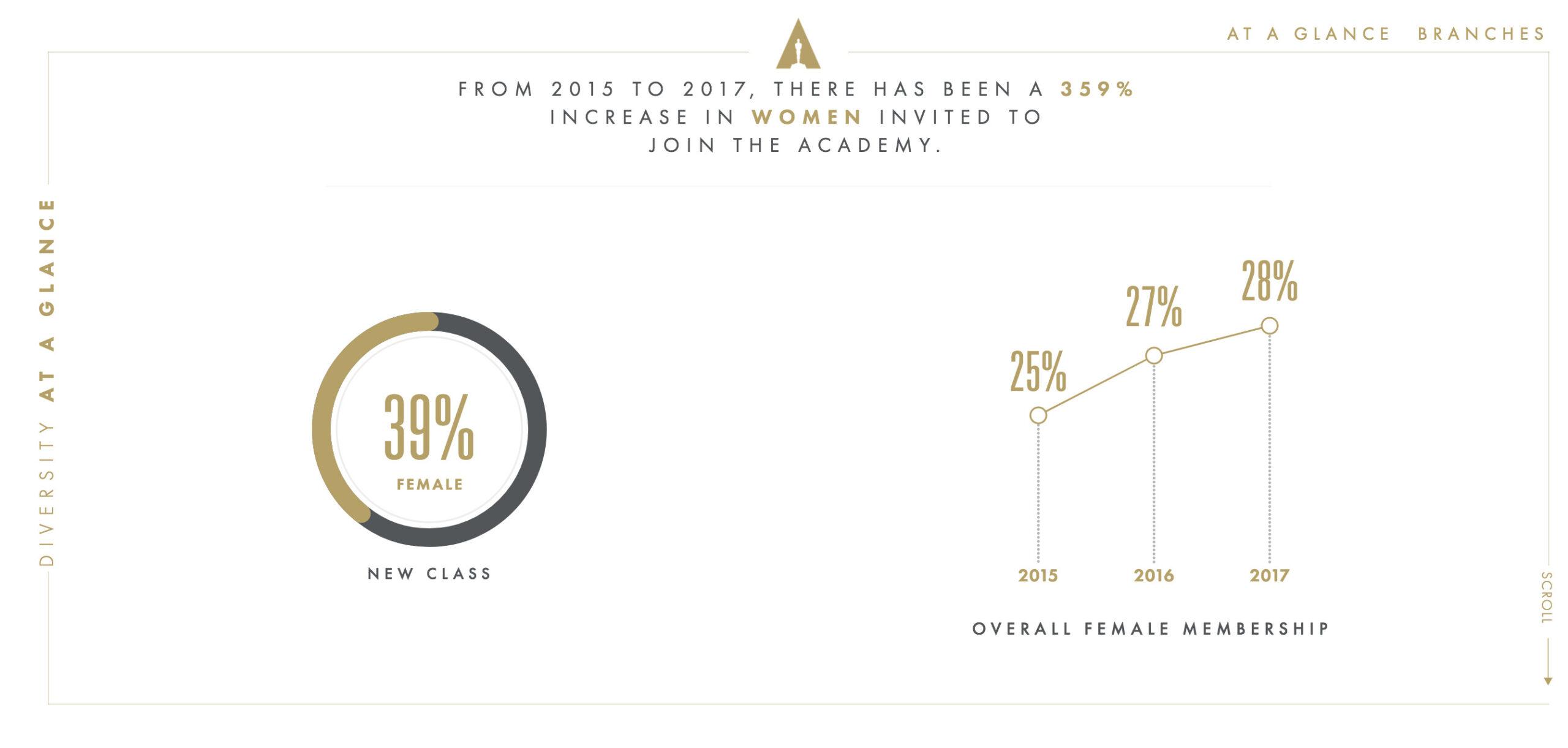

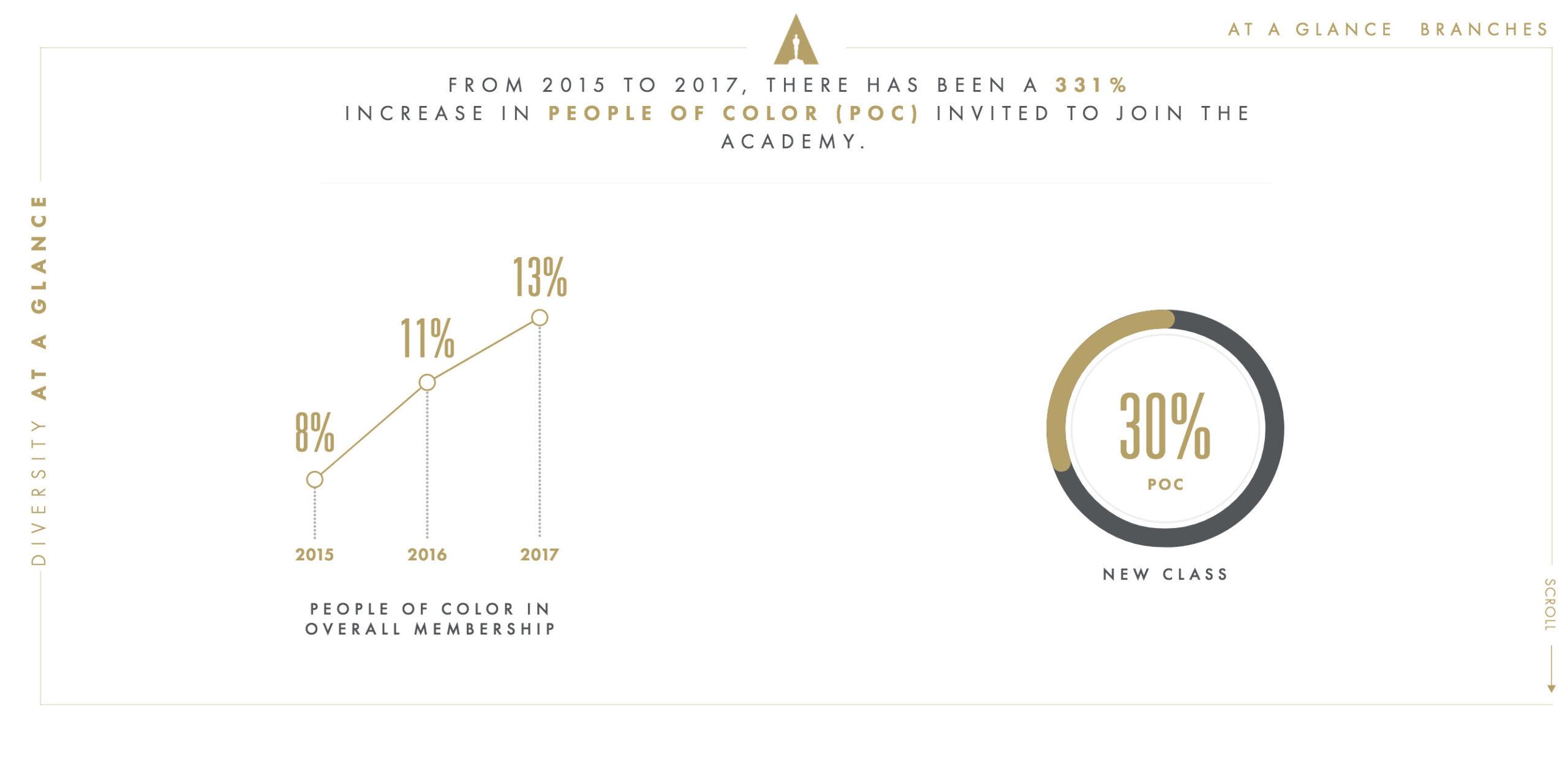

What does that mean, exactly? Let’s start with the data. At the end of outgoing Academy president Cheryl Boone Isaacs’s tenure, AMPAS created a slick, animated landing page to track its progress. AMPAS is famously sloth-like, taking decades to evolve. But when it began to change, largely during Boone Isaacs’s term, it happened quickly. Take, for example, the 2016 announcement on the organization’s website touting new members. Now look at the rollout in the 2017 version. That is pride in purpose. Now look at these staggering numbers about the 774 new members added last year, boosting the total body to more than 7,000 possible voters.

In what feels like a flash, the Oscars constituency has changed. In addition, older members who have not worked in the film industry in recent times—after an analysis is conducted of a 10-year period—have been expelled from the Academy, prompted by a significant change in 2016. So the Oscars are getting younger, less white, and less male. The movies the Academy will recognize will likely, in turn, mirror that change. Hence Moonlight’s win. Maybe. It is also reasonable and perhaps even essential to note that Moonlight, while not a box office giant, had eight nominations and was perhaps the best reviewed film of 2016. It was a juggernaut in its own way. Where the Academy’s growth feels most clearly reflected is in the huge support for Lady Bird (five nominations), and, naturally, Get Out (four nominations). Coming-of-age stories and horror movies don’t have much of a history at the awards. Neither film has a nomination in a craft category. And only five films in movie history have won Best Picture without a craft nomination: The Broadway Melody (1929), Grand Hotel (1932), It Happened One Night (1934), Annie Hall (1977), and Ordinary People (1980). That’s … not a good precedent.

But something else has changed: preferential balloting. When the Best Picture pool expanded to 10 nominees in 2009, the balloting system also changed—ballots asked that voters list their favorite films in order. If the no. 1 vote-getter did not receive 50 percent of the vote, the bottom vote-getter is eliminated and the second-place votes on the ballots that listed the ousted movie first then slide up and are dispersed to become no. 1 votes across the rest of the nominees. If then there is a movie with 50 percent of the vote, it wins. If not, another movie is eliminated and its votes are reallocated. This is confusing. I tried to explain it in this video, and our team made a helpful graphic to clarify.

Still confused? Here’s the thing: I am, too. With nine nominees for Best Picture, it feels like this year’s race will almost certainly go the route of preferential balloting. When I was explaining the concept in the above video, I imagined it as a strong case for The Shape of Water, which—with its broad swath of nominations across categories—seems like the kind of movie that touches a lot of different kinds of people and draws supporters deep into those 7,000-plus members. But is Get Out more likely to appear in second place on a large number of ballots? It depends on what gets knocked out. If Lady Bird or Call Me by Your Name struggle to garner much Best Picture support, it probably wouldn’t surprise anyone if that meant a raft of votes for Get Out. Likewise, if Darkest Hour or The Post fall out—and unfortunately, we’ll never learn the vote totals—I could see The Shape of Water rising. But what if, say, Phantom Thread draws the fewest votes (boo!)—how will the second-place votes be spread around? It’s impossible to know, of course.

And guess what? The Shape of Water and Get Out aren’t even the favorites in Las Vegas. According to Bovada, Martin McDonagh’s Three Billboards Outside of Ebbing, Missouri is a -115 favorite to win. I don’t see it. Coastal elitism writ large? Maybe, though bear in mind that most voters live in L.A. and New York. Then again, the next highest population of Academy members is in London, where the movie has been a phenomenon, reeling in the BAFTA for Best Film in February.

Seen from one angle, McDonagh’s tale of a vengeful and unrelenting woman who has been tormented by men and whose daughter was raped and murdered has a sincere resonance for a show that will spotlight the #MeToo movement that has swept across Hollywood. Seen from another, Three Billboards is a shrill, angry movie that misunderstands American racial politics and creates preposterous scenarios for all of its characters. I see neither pole—the movie feels specifically McDonagh, as imperfect and implausible as it is irreverent and uncouth. It is unreal, and unnatural. And for that reason, I think it won’t win, Vegas be damned.

Ultimately, I think the Academy will continue a recent trend. As Adam Nayman noted last month for The Ringer, “The splitting of the Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director has happened 26 times in 89 years, but four times in the past five years.” On Wednesday, I predicted that del Toro would win Best Director. I’m not wavering on that. But I am wavering on that feeling that del Toro’s movie will triumph at the end of the night. I see Jason Blum, Sean McKittrick, and Jordan Peele making the final speech. (Imagine Peele’s prepared remarks.) And if that happens, maybe the Moonlight Effect becomes the Moonlight Principle. Or maybe we should just call it reality.

The Prediction: The Shape of Water Get Out

The Upset Bet: The Shape of Water