There isn’t a place in the world less artistically meaningful than a shareholders’ meeting. And yet, there may not be a more vital space in the modern movie industry than Disney’s annual confab to discuss the portfolio strategy of the last mega-powerhouse studio standing. Earlier this month, there were twin expectations during chairman Bob Iger’s address to the gathered investors in the Walt Disney Company. The first one zeroed in on the future of Fox Searchlight, the famously keen and industrious boutique imprint that has operated since 1994 inside 21st Century Fox, and won four of the past 10 Best Picture Academy Awards, including this year’s prize for Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water. Fox Searchlight is a small outfit, producing approximately eight films a year, with a handful routinely emerging as awards contenders that eventually flower into box-office hits. (Think Slumdog Millionaire, Birdman, The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Descendants, and the recent Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri.) It’s a micro-studio that operates with precision, flexibility, and foresight.

Disney’s acquisition of Fox had some wondering if Searchlight—which finances movies at modest budgets (Shape cost just $19.5 million)—had a future inside the Mouse House, home mostly to globe-conquering entertainments. Since 2010, when it severed a 17-year relationship with Miramax, Disney has not overseen an arthouse production company. “We have every intention of maintaining the operations at Fox Searchlight,” Iger said on March 8. “We don’t have any plans right now to change what they do.” Searchlight, which will roll out Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs this week, can breathe a sigh of relief. For now.

The other matter at hand for Disney is, of course, Black Panther. Ryan Coogler’s indomitable Marvel adaptation has exceeded expectations among analysts, fanboys, and the culture at large. After topping the box office for the fifth consecutive weekend, it has created a new prism of success—with another $27 million this weekend, it sits at $605 million domestically, seventh all time, and within striking distance of no. 3, Titanic, at $659 million. Drink that in. The last time a movie ran the jewels for five weeks straight, it was another James Cameron event, Avatar. That turned out to be the second-highest-grossing movie of all time in America and the biggest by far in the world. America’s biggest? Another Iger concoction, Star Wars: The Force Awakens. “The real impact of this movie reaches far beyond the theater,” Iger said of Black Panther. In his 44 years at Disney, he noted, “I’ve never seen anything like the reaction we’ve gotten.”

Given the cultural walls it scaled and roadblocks of perception that it detonated, Black Panther is a movie moment without compare. Black, sophisticated (not just for a comic book movie), and elegant, it reset the conversation for what a blockbuster can do, and perhaps what one should be. And no young director has ever possessed the capital that Coogler has right now. Not black filmmaker—any filmmaker. Not Coppola after The Godfather, not Spielberg after Jaws, not Lucas after Star Wars, not Cameron after Titanic, all troubled productions that were far from sure things. With Black Panther there was a feeling of inevitability—perhaps not at this fever pitch, but between the 31-year-old Coogler’s steady ascent from Fruitvale Station to Creed and Marvel’s merciless, unrelenting power at the cineplex, Black Panther was assured success.

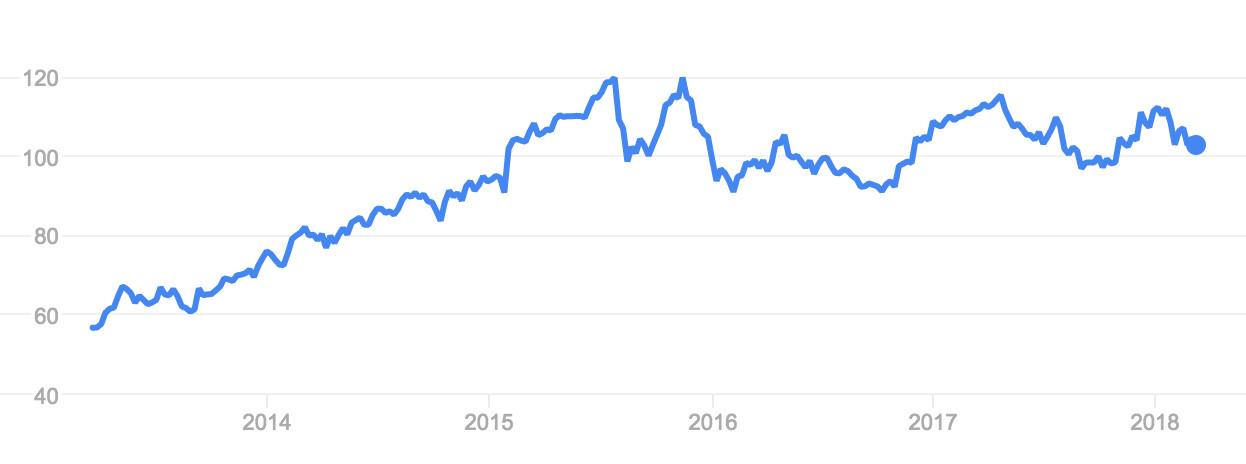

Months before its release, headlines screamed about presale figures. That it turned out to be both a complex and confident film as well as a popcorn-hoovering winner is a testament to the talent of the cast and crew assembled and also to the studio that takes only big swings. Black Panther’s storming of the gates means that six of the 10 biggest box-office grossers ever have been released by an arm of the Disney group, all within the past six years. The company also can claim 12 of the top 20. No other studio can claim more than three. The major studios are casually known as the Big Six: Warner Bros., Universal, Fox, Columbia, Paramount, and Disney. But these delineations don’t accurately reflect what Disney has managed to do in the past five years. Here’s a look at the stock price in that time.

In picking up the tab on Lucasfilm, Pixar, Marvel, and soon Fox (not to mention Touchstone, the Muppets Studio, and its own animation house), Iger’s reign has categorically and systematically acquired, remodeled, and rented out an entire sector of the entertainment business to its most adoring fans. Walt Disney once said, “Disneyland will never be completed. It will continue to grow as long as there is imagination left in the world.” In this century, Disney isn’t just the architect of the imagination—it’s the landlord.

My favorite scene in Black Panther is Shuri’s tour of Wakandan tech, a kind of updated James Bond-ian strut with Q through a Hall of Cool Shit. Look at these sick kicks! Check out this sweet Lexus with automated driving pod! Observe my energy-channeling vibranium super-suit with retractable necklace tech! Now picture Iger wandering that same hall, gallivanting among his collection of precious IP. The corridor dedicated to this year’s releases is perhaps the most stacked yet. After Black Panther and the muted response to this month’s A Wrinkle in Time at the box office, Disney continues a month-to-month assault on theaters the likes of which I can’t recall.

After the studio arbitrarily moved its release date up one week to April 27, Avengers: Infinity War is now tracking at a record-breaking presales pace, exceeding the standard set by Black Panther. One month later comes Solo: A Star Wars Story. Despite a raft of production issues that included the axing of directors Phil Lord and Chris Miller, the precedent set by the previous three Disney-shepherded Star Wars properties is clear and daunting: the similarly troubled Rogue One, The Last Jedi, and Force Awakens are three of the nine biggest movies ever domestically. Each one has cleared $1 billion worldwide. (No pressure.) Star Wars movies are events, no matter the director. Three weeks after Solo, on June 15, Pixar will release the first sequel to one of its most successful films, and a superhero story to boot, The Incredibles 2. In July, Marvel returns with Ant-Man and the Wasp, a movie that will likely be underestimated and then exceed those expectations, just like its predecessor, which earned $519 million around the world. In August, Disney Studios will revive Winnie the Pooh in the live-action Christopher Robin, starring Ewan McGregor and A.A. Milne’s anthropomorphic teddy bear. After taking September and October off, the studio returns with a new adaptation of The Nutcracker starring Keira Knightley as the Sugar Plum Fairy and Ralph Breaks the Internet: Wreck-It Ralph 2 (the original’s gross: $471 million) in November, followed swiftly by the Christmas movie event of the year: Mary Poppins Returns, starring Emily Blunt and Lin-Manuel Miranda, fresh off a tidy awareness campaign kick-started at the Oscars.

Every single one of these movies—11 in all—is based on a previously existing set of characters and every single one will be spit-shined to corporately magical perfection. Of its dominant 2017 releases, just one was an original story: Coco. It is an astonishing achievement that is both wearying and fascinating. For children, this is a glory, as satisfying a time as there has ever been. None of these movies is rated R, all are interconnected to a world in which the young audience has been investing, and each one comes gilded with merchandise, music, and Happy Meals over which to obsesses. These titles will make up a vast library for those kids (and overgrown fans) to cycle through repeatedly when the company launches its streaming service to rival Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu. It won’t hurt to have 50 of the 100 biggest movies ever on day one. As an adult, it’s easy to become cynical about why and how these choices are made—another Wreck-It Ralph movie, really? Then I watched the trailer, and … I’d like to see this.

In connecting and shepherding relationships with filmmakers like Coogler, Rian Johnson, Brad Bird, Jon Favreau, Lee Unkrich, Ava DuVernay, Andrew Stanton, James Gunn, and Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, the studio is also building a kind of trust among those keeping score on the creative decision-making. Maybe a Wreck-It Ralph sequel about the internet will be wonderful?

Lamenting about the movies that aren’t made anymore is a common refrain these days. We long for the James Brooksian rom-com, the midtier thriller, the ambitious sci-fi spectacle and ignore the versions of those movies that are actually released (The Big Sick, Wind River, Blade Runner 2049, respectively) when they don’t fulfill our platonic ideal. We think of the movie industry like a monolith, or like a great man pulling a lever behind a lime-green curtain. It isn’t that way, of course. It’s a fractured, confused landscape of creative people colliding with corporate interest. We know because Disney is managing the industry within an inch of its life, with the hearts and minds of stockholders as present in the strategy as the millions of children becoming emotionally addicted to their stories each year. (Ask the next 5-year-old you come across how they feel about Coco.)

The addition of Fox Searchlight—far more than the addition of Fox proper, with its X-Men, Avatar, and Kingsman franchises—could still be an intriguing wheel of cheese in Mickey’s manse. The one thing in the world that Disney proper doesn’t do well is win traditional film industry awards. In this century, the company has been nominated just twice in the major six categories at the Oscars, a 2009 Best Picture nod for Up and another for Toy Story 3 one year later. In fact, they represent just the fourth Best Picture nomination in Disney’s 80-year history. (Mary Poppins in 1964 and Beauty and the Beast in 1991). Awards just aren’t a part of the playbook, especially since Miramax left the fold. At Searchlight, it’s essentially the whole strategy. This year alone, it pulled in 20 nominations. Awards campaigning takes a particular kind of chutzpah and persistence. The kind of attention and adulation for which Disney doesn’t often have to ask. So now, with a slate to envy, another masterful acquisition, and perhaps the biggest movie of all time just six weeks away, Disney sits elevated, owner of nearly one-third of the moviegoing market share so far this year, a number that, if it held, would be a record by a wide margin. There’s not much reason to think that has to change this year. Disney is building a Wakanda of its own—impenetrable by the outside world, protected on all sides by a fierce and technologically advanced army, and prepared for the worst invasion. In 2018, it’s Killmonger-proof.