Peanut butter and jelly. R2D2 and C-3PO. Eric B. and Rakim. Some combinations can’t go wrong.

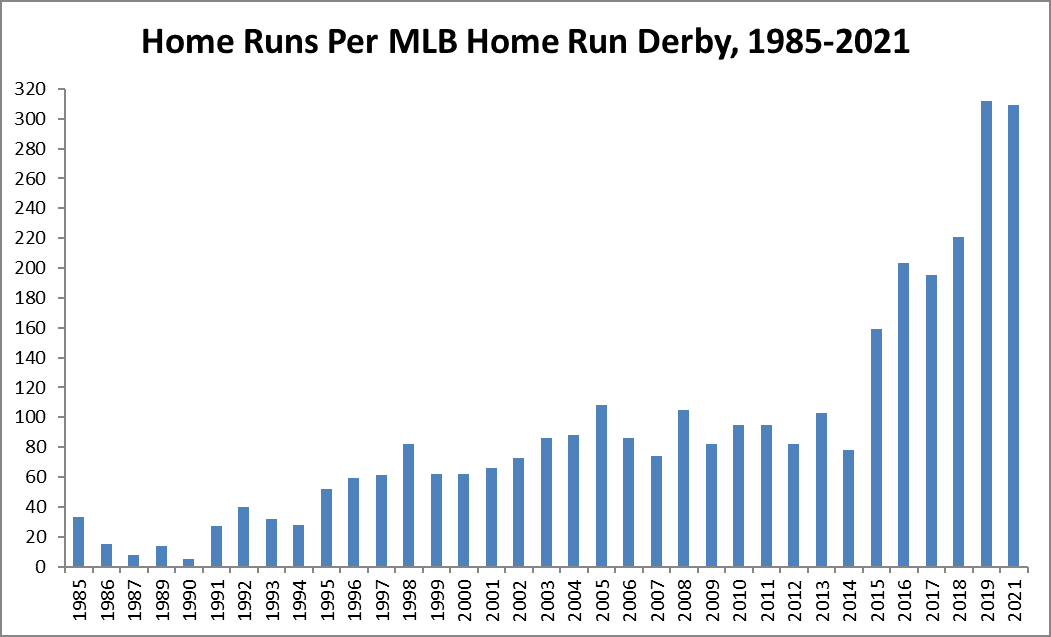

On Monday, Major League Baseball took one iconic combo—bats and balls—and paired it with another: the Home Run Derby and Denver’s Coors Field. Take the ballpark with the thinnest air, deactivate the humidor, raise the temperature to 90-plus degrees, and add eight of baseball’s biggest power hitters. The result, as anticipated, was a deluge of dingers. A cavalcade of dingers. An orgy of dingers. This was the second-home-runniest Home Run Derby in history, nearly matching the peak-home-run-rate year of 2019. When the balls and fans finally stopped falling, the derby was won not by the betting and fan favorite, Shohei Ohtani, or by the underdog and feel-good runner-up, Trey Mancini, but by the defending champion, Mets slugger Pete Alonso.

Alonso, who said on Sunday that he would win again, looked like he couldn’t be beaten—as if no matter how many homers his opponent hit, he’d be good for one more (or many more, if they’d let him keep going). As was the case in 2019, Alonso didn’t care who was supposed to win, who would have been the best story, or whether he was a candidate to be the Face of Baseball. He just wanted to smash massive dongs, and he could have kept doing it all night. By defeating Mancini, who mounted an inspired (and inspiring) performance a year after surviving Stage 3 colon cancer, Alonso joined Ken Griffey Jr., Prince Fielder, and Yoenis Céspedes as a multi-time derby winner. At 26, he has plenty of derbies ahead of him if he wants to keep coming back—and from all appearances, there’s nothing he’d like more than to make mashing at the derby a staple of his summers. This could be the beginning of a derby dynasty, assuming MLB doesn’t ban him for dominating too much.

Alonso, aided by the pinpoint control of 64-year-old BP pitcher (and Mets bench coach) Dave Jauss, dispatched Salvador Pérez with a 35-homer fusillade in the first round, did away with Juan Soto in the semis, and topped Mancini’s 22 in the finals. Swinging colored lumber and jamming to the tunes on the Coors Field sound system (or possibly a soundtrack inside his own head), he became a homer-hitting metronome, a being specifically constructed to slam again and again. At no point did he look nervous, rushed, or gassed, and even injuries to ball boys couldn’t disrupt his rhythm. While other hitters sprayed dingers out to all fields, Alonso locked in on left field, pulling all of his taters except two he sent to center. Soto (520) and hometown hero Trevor Story (518) both outdid Alonso’s longest blast of 514 feet, but Alonso outlasted all comers to claim both the bragging rights and the $1 million prize—almost double his 2021 salary. (Maybe being drastically underpaid is a powerful incentive.)

In the lead-up to the derby, two characters took up most of the mile-high oxygen: Ohtani, and Coors itself. Ohtani, MLB’s home run leader, was going to get the national shine that Angels games don’t often afford him, putting on a display of batting-practice power the day before seizing the spotlight again as the AL All-Star team’s starting pitcher and leadoff hitter. Coors boosts scoring more than any other park, but with the dinger-suppressing humidor in effect, it’s no longer the homer-happiest park. Wisely, MLB benched the humidor on Monday in the interest of maximizing distance. Aaron Judge’s record for the longest derby dinger tracked—513 feet in 2017—seemed certain to fall, and it didn’t last long.

Ohtani hits the ball harder than any other competitor, which has been the best recent indicator of derby success. But the derby is an unpredictable beast. Todd Frazier won one. Bobby Abreu won one. Garret Anderson won one. Before Alonso lapped him on Monday, the all-time leader in derby dingers was Joc Pederson. Ohtani, who hadn’t taken on-field batting practice since Opening Day, blasted balls in BP at Coors in 2018 and launched one 510 feet just before the derby began. But once his swings counted, he started slowly, ripping doubles down the line. His pitcher, Angels bullpen catcher Jason Brown, was wild compared to Jauss, and he worked more slowly than some of his counterparts. But once Ohtani found his groove, he ran his total up to 22, which tied Soto and set up a swing-off. Then the two tied again, at six, which left them with three swings apiece.

Soto, who was surrounded during breaks by All-Stars who swarmed him like cornermen between boxing rounds, put his preternatural plate discipline to use. He watched a few balls go by, waited for the ones in his wheelhouse, and went a clutch 3-for-3, putting pressure on Ohtani, who flubbed his first swing to end the suspense. The Japanese star, who recently became the first AL player to homer 16 times in a 21-game span, was out of the running, though the 2016 NPB Derby champion did drive one 513 feet before he succumbed. (In a slight letdown, moonshot machine Joey Gallo also exited in the first round, succumbing to Story.)

Ohtani is breaking baseball’s rules both figuratively and literally: Not only has he changed our understanding of what’s possible in the sport, but his unique skill set and popularity persuaded MLB to rewrite the rules of the All-Star Game to allow him to play both ways. But on Monday, he couldn’t quite catch Soto, whose uncanny sense of the strike zone overshadows how hard and far he hits the ball. Even if Ohtani had squeezed by Soto, he would have had a hard time topping Alonso. At least losing early helped him conserve strength for the showcase to come.

In the absence of the Juniors (Vladimir Guerrero Jr., Fernando Tatis Jr., and Ronald Acuña Jr.), the giants (Judge and Giancarlo Stanton), or other name-brand batters like Mike Trout and Bryce Harper, the 2021 derby field lacked a little star power. (No offense to Matt Olson.) But regardless of which challengers have thrown their bats into the ring, the derby has been a treat since the elimination of outs and the advent of brackets and timed rounds in 2015. Even people who don’t like home run highlights dig the derby now. In the past several years, the event has been buoyed both by the new format and by a string of memorable individual dinger displays: Stanton in 2016, Judge in 2017, Harper at his home park in 2018, Guerrero (and Alonso) in 2019. Alonso’s first-round fireworks, the showdown between Ohtani and Soto, and Mancini’s emotional comeback from cancer treatment supplied the stories to go with the powerful feats.

This year, the rules were tweaked again: The timed rounds were trimmed from four minutes to three for the quarters and semis, and to two for the finals. But every hitter received 30 seconds of corporate-sponsored bonus time, plus an additional 30 seconds if they hit at least one ball 475 feet (which was almost automatic at Coors). In addition, the former restriction on throwing a ball before the previous blast landed was removed, which placed an even greater emphasis on speed. In this version of the derby, the market inefficiency was the fast-paced BP pitcher, and a few of the throwers seemed to take their sweet time, even turning to see where some big flies landed. Although the bond between batter and hand-picked pitcher can be touching at times, the inconsistency among arms made me wish for one rubber-armed hurler who could throw to each hitter, or even an anthropomorphic pitching machine. I’d rather the results be attributable entirely to the batters, not a combination of batters and bench coaches or bullpen catchers.

While the no-holds-barred bombardment seemingly went over well in the park, it made for a chaotic and sometimes-inscrutable broadcast, as even split screens couldn’t keep up with every swing while tracking every trajectory. Although the distance of every dinger was listed at Coors Field and online, ESPN chose not to report the distance of each drive on either of its stat-packed broadcasts, opting instead for averages, maximums, and sporadic mentions by the broadcasters. At times, that made for frustrating at-home viewing; I wanted more time and screen real estate to admire and measure the most majestic flies before gearing up for the next one.

Last month, Alonso suggested that MLB juices and deadens the baseball to selectively suppress free-agent earnings. That isn’t why the ball has been deader this season, but it’s true that it’s not carrying quite as far: The average distance on hard-hit flies is down relative to 2019. By historical standards, though, the ball remains mega-juiced. The rate of homers on contact is the third highest in history, behind 2019 and 2020—and that’s with more warm-weather months still ahead. The still-lively ball, coupled with Coors and the timed format, made for another year of ridiculous dinger counts. This is the era of record home run rates, not only in the games but also in the exhibitions.

By the time Alonso wound down in the first round, there had already been more homers hit than in any derby from 1985 to 2014. We can’t say we were cheated, or that Coors didn’t deliver.

If there were a way for the logistics to work, the derby would be at Coors Field every year. As it is, this was the first derby in Denver since 1998, when surprise participant Griffey—who was on hand for the festivities on Monday—took his second of three crowns. Griffey’s total is the target for Alonso next year. The pandemic stopped Pete from winning a derby, but MLB batters haven’t held him back yet.