The “You had to be there” cliché is a frustrating part of sports parlance, especially for a writer. It’s my job to describe, explain, and analyze what happens on the field precisely so you don’t have to be there to appreciate or understand a player or an event. It’s not always an easy task—the matter-of-fact dominance of a Mike Trout or Jacob deGrom is far rarer than the chaotic playoff game, which splurts messily and indiscriminately from one inning to the next. But that’s the challenge, to distill a picture into 1,000 words.

With that in mind, consider Vladimir Guerrero Jr.

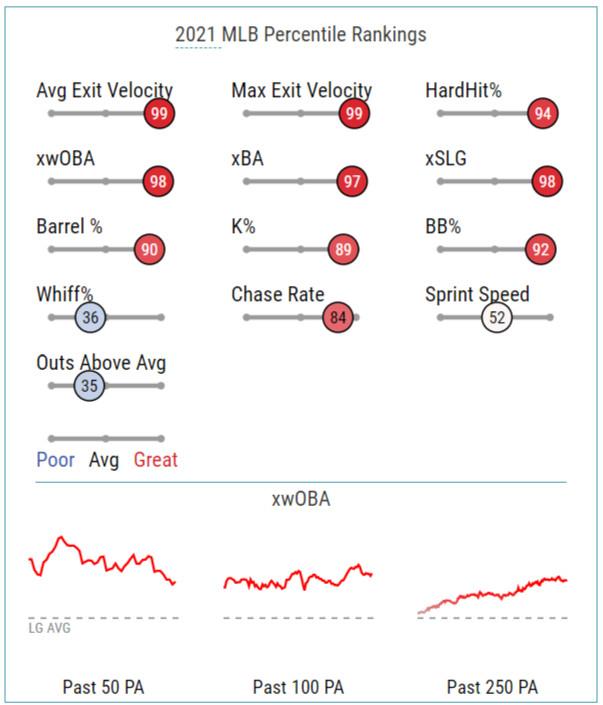

As of Monday morning, the 22-year-old Toronto slugger is leading the American League in all three triple-slash categories, wRC+, and home runs. Then there are the fancy stat categories, for which Baseball Savant has generated a handy little chart to illustrate where Guerrero ranks relative to his competition.

Usually when you see that many red balls on a table at one time, Ronnie O’Sullivan appears to clean up the mess.

In some ways, I’m relieved that Guerrero’s breakout season is such a quantitative outlier, because it’s very hard to explain on paper what it’s like to watch him. His strength, his coordination, his command of the science of hitting are all self-evident. So too is the overflowing self-confidence that’s common to almost all of today’s top young players—a confidence that stems from the knowledge that they are impossibly good at an impossibly difficult job.

Unfortunately, my trusty bag of adjectives doesn’t contain anything suitable for Guerrero. Precocious, preposterous, prodigious, yes. But nothing captures the sensation of watching Vladito line up a fastball and blast it effortlessly over the batter’s eye. And “effortlessly” is the key—he doesn’t have Shohei Ohtani’s unfurling trebuchet swing, or Bryce Harper’s furious pull-side yank, or Prince Fielder’s screw-himself-into-the-ground ferocity. Guerrero can just knock a baseball 450 feet with all the conspicuous effort of a man shoveling mulch in the backyard. There’s not really a word for that—it just makes me giggle.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Vladito’s breakout season is how unsurprising it is. Guerrero entered this season with a career .269/.336/.442 slash line, 24 home runs, and 39 doubles in 183 games—a little more than a full season’s worth of playing time. And that’s … fine, I guess. It’s more or less what Christian Walker produced in 2019.

But Guerrero has never been an ordinary average first baseman. Back in April, Guerrero was chatting with Albert Pujols before an Angels–Blue Jays game, and as the conversation petered out, Guerrero introduced teammate (and noted Pujols admirer) Santiago Espinal to the three-time MVP. The encounter was caught on video and went viral, a heartwarming vignette of intergenerational collegiality. But as much as the focus was on Pujols and Espinal, the clip probably said the most about Guerrero. Having just turned 22, and not having achieved that much in the majors yet, Guerrero should have had more in common with Espinal than Pujols. And yet there he was, shooting the shit with one of the three or four best ballplayers of the 21st century, almost as equals.

A lot of that can be explained by the fact that Guerrero, the son of a Hall of Famer, grew up viewing players like Pujols as merely his dad’s colleagues. But Guerrero fils has already amassed a star quality of his own—one that extends beyond his name.

Whether Guerrero is the best hitter in baseball right now is a complicated question. Less complicated is the proposition that Guerrero, as a minor leaguer, was the best hitting prospect in about 10 years. In 2015, the Blue Jays signed the then-16-year-old to a $3.9 million deal that not only ate up their entire international bonus allotment, but it also required them to trade two future big leaguers to the Dodgers to scare up an additional $1 million and change to secure Guerrero’s signature. Within 18 months, Vladito was a top-30 prospect in all of baseball. A year later, he was in the top three, and a year after that he was the consensus no. 1. In order to find a player with such high offensive expectations, you’d have to go back to Harper at the very least.

Even when he was beating the ball into the ground and putting up modest home run totals, there was always the expectation that Guerrero, as a mature big leaguer, would hit like Pujols. The only question was how he’d turn potential into reality.

The most headline-grabbing change from last year to this year is the fact that Guerrero showed up to camp in—to invoke another cliché—the best shape of his life. Vladito is still a wide, stocky figure, listed officially at 6-foot-2 and 250 pounds. But by his own account, he reported to camp some 42 pounds lighter than last year, or 14 times as much as Regina George wanted to lose. (This must be the most successful new workout plan since Kanye West got Ella-May from Mobile, Alabama, to date outside her family.) Baseball isn’t a sport where lighter is necessarily better, but Guerrero seems bouncier than he has been in previous years. One of the more eye-popping revelations from Guerrero’s Statcast profile is his sprint speed, which is apparently now slightly above the league average.

Guerrero’s stunning productivity at the plate can’t just be attributed to conditioning. Since he was a teenager, Vladito has exhibited hit and power tools that are rare individually and nearly unheard of in combination. And this year, for the first time, he’s harnessing both to their fullest extent. There isn’t one completely revolutionary change to his batted ball profile, like Max Muncy’s newfound selectivity or the fly ball–heavy approach that suddenly made Matt Carpenter one of the best home run hitters in the league. Instead, Guerrero has made a few small-to-moderate changes that have had a profound effect on his offensive output.

The first place to look is Guerrero’s ground ball–to–fly ball rate, which currently sits at 1.36. That’s tied for 45th out of 144 qualified hitters, which isn’t extreme by any means, but is also way down from the 1.96 GB/FB ratio Guerrero posted last season, which ranked 11th out of 142 qualified hitters. While fast guys with great bat control—like David Fletcher and Tim Anderson—can be quite productive putting the ball on the deck that frequently, power hitters like Guerrero need to get the ball in the air more. This was a well-known weakness in Guerrero’s game in years past, and he’s gone a long way toward correcting it.

What does that mean in statistical terms? Well, in 60 games last year, Vladito hit 100 ground balls, 51 fly balls, and 32 line drives; this year, through 57 games, he’s hit 79 grounders, 58 fly balls, and 32 line drives. Through a full season, that’s somewhere between 50 and 60 grounders turned into fly balls. And when you’re hitting .228/.228/.228 on grounders and .421/.414/1.456 on fly balls, as Guerrero is, those 50 or 60 extra balls in the air add up.

Guerrero has also gotten a little more selective this season. He inherited his father’s ability to hit basically any pitch thrown in the general vicinity of the plate, but the younger Guerrero is not only much more patient than his dad, he’s become much more patient than he was even two years ago. His chase rate—the percentage of pitches he swings at outside the zone—has dropped from 28.9 percent in 2019 (the 47th percentile of most selective hitters) to 21 percent this year (84th). Moreover, his contact rate on pitches outside the zone has gone through the floor, from 58.8 percent to 40.8 percent.

That might look like a bad thing on the surface, but the practical impact is a little counterintuitive. One of the statistics Statcast tracks is expected weighted on base average on contact, or xwOBACON (pronounced “ex-whoa-bacon” if you’re feeling saucy). In the simplest terms, that’s a measure of how productive a hitter should be based only on the quality of contact he makes.

The league leaders in xwOBACON fall into two categories: The first is ultra-selective hitters like Muncy, Trout, and Aaron Judge, who (1) tend to lead most offensive statistical categories, and (2) don’t take the bat off their shoulder for anything they can’t crush. The second includes hitters like Mike Zunino and Tyler O’Neill, who swing and miss a lot, but are strong enough to dismember a hippopotamus with their bare hands. So when they swing, they either make contact and hit the ball to Mars, or they miss entirely, which xwOBACON doesn’t penalize them for. That’s what Guerrero is doing outside the strike zone. While swinging and missing is obviously not an ideal outcome, it can still keep you in an at-bat (as long as it’s not strike three). Swinging and making weak contact, on the other hand, offers no such reprieve.

While Guerrero’s 2021 in-zone swing and contact rates are more or less unchanged from years previous, his strikeout rate is slightly down, and his walk rate is up nearly 6 percentage points from last year. For a hitter with his barrel control, that says he’s refined his judgment of the strike zone and is covering a smaller area more effectively. Last year he was known to chase pitches that came within 6 inches of either the top of the strike zone or off the outside corner. Now he’s not. And while he is chasing more on pitches low and in, his xwOBA on pitches low, inside, and out of the zone is .430, comparable to his overall xwOBA of .426.

Vladito’s ability to crush his pitch has never been in doubt; he famously hit 91 home runs in the 2019 Home Run Derby, less than three months after getting his first taste of big league action. What he’s doing now—and doing better than almost anyone in baseball—is identifying his pitch, and getting more bang for each swing than ever before. We’re already out of adjectives to describe his play; if he keeps hitting like this, we might run out of baseballs, too.