On July 4 in Pittsburgh, home-plate umpire Joe West found himself in the middle of a managerial tiff. In the top of the fourth inning, Pirates pitcher Jordan Lyles followed Pittsburgh’s purpose-pitch playbook and repeatedly threw high and tight to the Cubs’ Javier Báez. Chicago manager Joe Maddon, attempting to protect his player and, perhaps, demonstrate some intensity to his dissatisfied boss, Theo Epstein, started yelling from the dugout, either at West or at his counterpart on the Pirates’ side, Clint Hurdle. The long-tenured West, who’s infamous for his short fuse, ejected the Cubs skipper from the game, prompting Maddon to emerge from the dugout and home in on Hurdle.

West, who’s not known for deescalating tense situations, seemed to do a decent job of defusing this one. After the ejection, he body-blocked Maddon, unfazed by the manager’s slow-motion spin move. In the fifth, Pirates reliever Clay Holmes beaned the Cubs’ David Bote with the bases loaded; West warned both benches, but knowing that the run-plating plunking was unlikely to be intentional, he didn’t toss Holmes. After that, the tensions subsided.

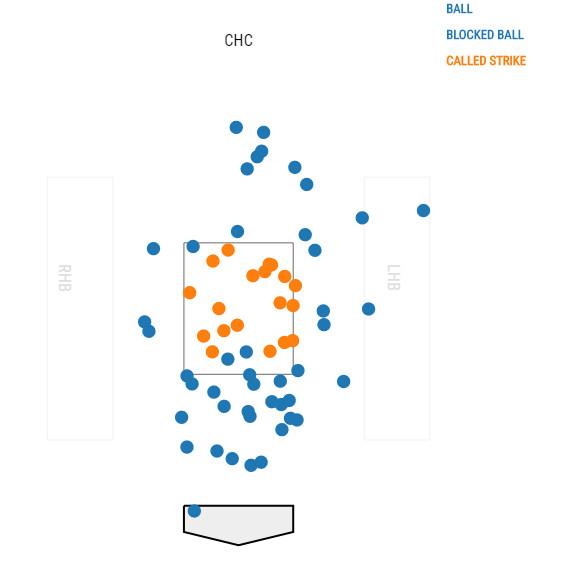

Lost amid the drama of Maddon’s crusade and West’s swift response was a possible first in West’s 40-plus-year career: Behind home plate, he umped a perfect game. When the Cubs were pitching, West made every ball and strike call correctly, if we define “correctly” as “in accordance with the rule book zone.” Given that hitters aren’t all the same size and that strike zones have different dimensions, with variable top and bottom boundaries, it’s difficult to capture umpire perfection in one pitch plot, but the graph of West’s calls on Cubs pitches still shows that he had a good day.

Since the start of 2008, the first full season when pitch-tracking systems were installed in every stadium, MLB players have recorded 51 cycles, 48 triple plays, and 38 no-hitters (not counting combined no-hitters). All those infrequent events have occurred more often than the umpire perfect game. Over the same span, home-plate umpires have made every pitch call correctly on one team only 24 times in games that lasted at least nine innings, with West’s the most recent. That’s roughly once per 1,200 games, or a little more than twice per season, on average. It’s not quite as uncommon as the pitcher perfect game—we’ve seen only six of those since ’08—but it’s rarer than most of the events considered deserving of push notifications.

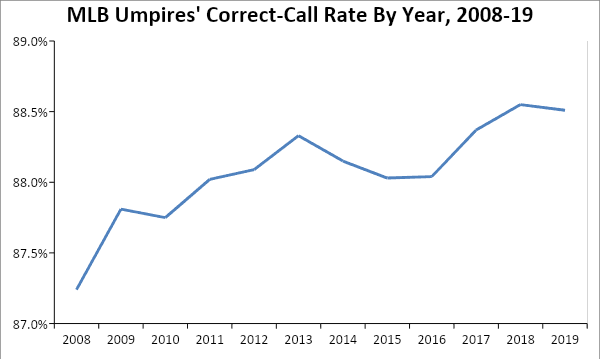

Umpire perfect games are so scarce because umpires make many calls in most games and because it’s difficult to call pitches precisely when they’re flying as fast and moving as much as major league offerings do. MLB umpires are presumably the best in the world at that challenging task, but they still succeed only about 88.5 percent of the time, a rate that’s risen slightly since the start of the PITCHf/x era. The graph below shows the leaguewide correct-call rate by year, according to data provided by Baseball Prospectus writer and researcher Lucas Apostoleris, who used park-corrected pitch locations and the strike-zone definition developed by former BP analyst Mike Fast, which incorporates stringer-recorded bottom boundaries, batter-height-dependent upper boundaries, and horizontal boundaries that correspond to the two points where the edge of the ball touches the plate.

If we discard a few games with missing pitch data, the average number of called pitches per game is roughly 156. The average number of called pitches per team per game is half that, or about 78. If pitches were completely independent events, and calling balls and strikes were like flipping a weighted coin with an 88.5 percent chance of a correct call, then through random variation alone we would expect umpires to call every pitch on one team correctly about once every 13,600 games, or less than once every 5 1/2 seasons.

Umpire perfect games occur much more frequently than that, which is what we would expect. For one thing, some games require fewer calls, which makes it easier for umps to run the table. No umpire on record has achieved perfection when forced to make more than 71 calls on a team. Naturally, no umpire has been perfect for both teams in a game; Scott Barry came closest on July 22, 2017, when he made 138 of 142 calls correctly (97.2 percent). When West was perfect on Cubs calls, he nailed only 87.5 percent of his calls on Pirates pitches.

Umpire Perfect Games, 2008-19

For another, some umps are better than others, although the differences are subtle. (Among the 114 umpires with at least 5,000 called pitches since 2008, the range between the most accurate and least accurate umps is narrower than 4 percentage points, ranging from 86.2 percent at the low end to 90.1 percent at the high end.) And perhaps most important, umps aren’t computer programs—not yet, at least—and their game-to-game accuracy rates aren’t entirely random. Some games feature more favorable pitch-calling conditions than others. And although they don’t have to hit or throw, umps get into grooves just like hitters and pitchers do.

You know how hitters will sometimes say the baseball looks bigger when they’re streaking and smaller when they’re slumping? Umpires say the same. “There were certainly some days the ball looks like a beach ball, and other times it looks like a marble,” says former MLB umpire Dale Scott, who broke into the big leagues in 1985, became a crew chief in 2001, and retired in 2017, working three World Series, three All-Star Games, and nearly 4,000 regular-season games along the way. The start of Scott’s career predated pitch-tracking technology, and he continued to ump after the introduction of the QuesTec, PITCHf/x, and Statcast systems, so he saw how that tech helped make umps more accurate. He agreed to give us the rundown on why umpires’ accuracy fluctuates from game to game even though the strike zone essentially stays the same.

Scott notes that the backdrops of some ballparks can make it harder to pick up pitches; the batter’s eye is also the umpire’s eye, and if it doesn’t provide a stark contrast to the baseball, the ump is in trouble.

“The Rangers used to love to throw Nolan Ryan, if they could, on Sundays,” Scott says. “It was a 6:00 start, and they would fill up the batter’s eye with people, because they usually would get a great crowd when Nolan would throw. It was bad enough with the sun hitting the center field bleachers at that 6:00 start time, and the glare that that caused. But then you have people in the background of the pitch, which you normally don’t have, wearing white shirts or moving.”

Another nightmare scenario occurred in Game 4 of the 1997 ALDS between the Orioles and the Mariners. The game started in the late afternoon to accommodate the TV network’s needs, and the sun was gleaming off a silver building in center, directly behind the left arm of Seattle starter Randy Johnson. With a later start time, a right-handed pitcher, or a shorter southpaw than the 6-foot-10 Big Unit, the building wouldn’t have bothered Scott, but that confluence of factors conspired against him. “His pitch was literally coming out of a glaring silver building, so good luck with that,” Scott says. Nine of Johnson’s first 14 outs came via strikeouts, so the hitters were having a tough time too.

Situations like those are out of the ordinary, but even when the backdrop is dark and empty and the pitcher isn’t a giant, environmental conditions can still impact an ump’s accuracy. “Shadows are a bitch,” Scott says. Other obstacles include pitchers who employ dramatically different styles—Scott cites a game in which flamethrower Juan Berenguer faced off against knuckleballer Charlie Hough—hitters who crowd the plate, and pitchers who work inside, like the Pirates on the day when West was perfect for the Cubs but imperfect for Pittsburgh. If the hitter is crowding the plate and the ball is breaking toward him, Scott says, “Your field of vision as an umpire, that window that you use, what we call the slot, it seriously shrinks.” Catchers who are especially adept or inept at receiving pitches may also invite more inaccurate rulings, much to their teams’ delight or dismay.

If you’re walking off the field and somebody on the losing team says, ‘Hey, you had a great game today,’ that means a lot more than somebody on the winning team, for obvious reasons.Dale Scott, former MLB umpire

On a day when an umpire encounters one or more of these problems, some inaccuracy is inevitable, even if the ump tries not to let the problem impair their confidence. “You don’t sit back there and think, ‘Oh gosh, the background’s really bad. Well, I’m just going to miss a few today,’” Scott says. “That’s just not your mind-set. But the reality is you may, because that same pitch in a perfect scenario, you probably get right every time. But you may miss it once in a while in a situation where the background is tough or the hitter or the catcher is crowding.”

It’s intuitive that those external factors could sway an umpire’s accuracy. It’s a little less obvious, though, that an umpire can also screw up their own performance by messing with their mechanics. Even though the umpire appears to be making more or less the same movements from pitch to pitch—stand, crouch, signal—they still have to have their timing down.

“Timing is one of the most important things you have,” Scott says. “If your timing is too quick, you’re going to miss pitches or plays, because you’re not letting the entire play happen and you’re not letting it, for that brief, brief, quick moment, replay in your mind before you actually call it one way or the other.” If Scott felt his timing was off, he’d return to the checklist he learned on the first day of umpire school, reviewing his head height, his foot position, and whether he was crouching too late as the pitcher delivered and thus seeing the ball later than he should. He compares that process to a driver on an open road who has one hand on the steering wheel and the other arm out the window; when traffic gets congested, those hands might return to the 10 and 2 positions on the wheel as the driver recalibrates and gets back to basics.

There’s an element of luck to any umpire perfect game, just as there is to virtually any uncommon accomplishment by a player or a team. (Many a no-hitter has hinged on a spectacular defensive play.) But there’s still considerable skill involved. Unlike a pitcher who throws a no-hitter, though, an ump doesn’t get mobbed after completing a perfecto. “You don’t really get a lot of compliments during the game,” Scott says, although occasionally a player would pay him one later. He remembers going over the ground rules before a game the day after working behind home plate and hearing pitcher Tim Belcher trying to get his attention from the Mariners’ dugout.

“With his two hands, he drew a square, meaning the strike zone, and then he put a thumbs up,” Scott says. “What he was saying to me was, ‘Hey, you had a great zone last night.’ Of course, he probably won. … You kind of take it with a grain of salt, depending on where it comes from. If you’re walking off the field and somebody on the losing team says, ‘Hey, you had a great game today,’ that means a lot more than somebody on the winning team, for obvious reasons.”

Former catcher John Baker, who’s now a mental skills coordinator with the Cubs, says via email that he was always honest with umpires, but only in a “detached way,” partly because he believed that berating them only made them more erratic. “I would say great job at the end of the game if I felt he did a great job,” Baker says. But mostly, he continues, “I let my silence speak for itself. They know they are having a good game based on a lack of interactions. If no one is complaining, they know.” The hallmark of an umpire perfect game, then, is that no one watching from home notices it’s happening.

Scott says he wasn’t pleased when the QuesTec system started evaluating umpires, but he came to view the feedback as a necessary corrective. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, he admits, “We had gotten way too off the plate, and the high part of the zone got way too low, and the low part of the zone had come up a little bit. The book definition of the strike zone and what we were calling in practicality every day just weren’t lining up. We needed to rein that in a little bit, and that’s exactly what that system did.” The variation in umpires’ strikes zones decreased significantly after QuesTec was installed in 10 parks in 2002.

MLB’s current rubric for scoring umpires’ performance on pitches, the Zone Evaluation system, claims that umpires are 97 percent accurate, a number that Scott also cites. That seemingly inflated figure—which may stem from MLB’s decision to discard certain pitches when the catcher blocks the ump’s view—is something of a mystery, considering that public research consistently yields lower figures. (An inquiry to an MLB spokesperson didn’t clear up the discrepancy.) Because MLB’s baseline is so much higher, the Zone Evaluation system awards umpire perfect games much more often than the Baseball Prospectus method. Scott never achieved a perfecto for both teams, but he remembers one game when the system said he missed one pitch. After reviewing the video, he knew he’d called it incorrectly, but he still appealed the judgment to Matt McKendry, MLB’s senior director of umpire operations. “I said, ‘Matt, please, give this one back to me, let me go a hundred one time,’” Scott says. “And he laughed and didn’t give it to me.”

Every observation about the difficulty of umpiring doubles as an argument in favor of removing the job from human hands. As part of an experimental partnership with MLB, umpires in the Atlantic League are currently calling pitches with the aid of TrackMan technology, and it’s not hard to imagine robot umps making their way to the majors in the not-too-distant future. Some technical hurdles remain: In the Atlantic League, the system itself and the earpiece that relays its readings to the umpire have malfunctioned midgame, and pitch-tracking technology isn’t as accurate in real time as it is after post-processing, which makes it troublesome to track umpire perfect games as they happen. (In the majors, umpires can’t access their home-plate performance reviews until the morning after the game.) In theory, though, the robots could umpire a perfect game almost every time.

Scott understands the appeal. “Everybody wants the call to be perfect,” Scott says. “And I get that. We do too.” However, he cautions against unintended consequences of the pursuit of perfection. “There are rules out there for a reason, but it doesn’t mean that you just 100 percent, without any thought process, enforce every rule all the time,” Scott says. He adds, “There’s an art to umpiring, and there’s a science to it. The science is these computers, and they have no art to them whatsoever. They just call whatever they’re programmed and told to call.”

That’s OK in most cases. But one reason human umps aren’t “perfect” more often is that they can be judicious about when not to call a strike. As an example, Scott cites a pitch moving down and away that just scrapes the strike zone at the front of the plate on the outside corner, at the lowest part of the hitter’s knee. “The catcher catches it 2 or 3 inches outside the plate and about two or three inches off the ground,” Scott says. “Technically that’s a strike … by book rule. A human umpire isn’t probably going to call that a strike because it doesn’t look like a strike. It’s not accepted as a strike.” Pitches like that have occasionally caused acrimony in the Atlantic League, because hitters aren’t used to seeing those calls go against them.

Of course, MLB could conceivably amend its definition of the strike zone or program the robots to call balls on certain hard-to-hit pitches. But there is another human-ump imperfection that may make baseball better: the consistent tendency for the zone to expand or contract based on the count. Scott says umps don’t consciously adjust how they call pitches because of the count, but it’s inarguable that the zone is typically slightly smaller than normal on 0-2 and slightly larger than normal on 3-0. Although that may seem unfair, players expect the size discrepancy, and it probably helps hitters and pitchers who fall behind in the count dig out of those holes. That quirk creates more reversals of fortune, which makes for more competitive and compelling plate appearances. Human umps’ fallibility also places more emphasis on catchers’ receiving skills, allowing more leeway for backstops’ talent and technique to influence the game.

Maybe those benefits aren’t enough to outweigh the downsides of tasking humans with a job that’s almost impossible to do perfectly. Robots don’t blink, and they wouldn’t be fazed by a blinding building, an ultratall left-hander, an unpredictable knuckleball, or a rushed crouch. In the future, perfection behind home plate will probably be the norm. If so, someday we may remember these rare human-ump perfect games as visions of what was to come and quaint relics of a formerly flawed game.