The Cleveland Indians entered the 2019 season as a near-lock to play in October, and for good reason. They were coming off three straight AL Central titles, plus a trip to the World Series in 2016 and a 22-game winning streak in 2017, while three of their division competitors (Detroit, Chicago, and Kansas City) were mired in rebuilds, and the Twins, who appeared in the wild-card game in 2017, took a step backward the following year. The Indians looked like the best team, by far, in baseball’s weakest division. We here at The Ringer all but wrote off this division race in March and Baseball Prospectus put Cleveland’s Opening Day playoff odds at 90.7 percent, second in baseball behind the Houston Astros.

The first two and a half months of the season have been a hell of a ride for the other 9.3 percent. While Minnesota is off to a 44-21 start, a 109-win pace and the joint-best record in the American League, Cleveland has been ravaged by injuries and rattles into mid-June as about a .500 team. And that’s not an artifact of bad luck or one outrageous swoon—Cleveland has a run differential of minus-five, and has never been more than five games over .500, nor more than one game under .500. They’re playing like an average team because, at this point in the season, that’s what they are.

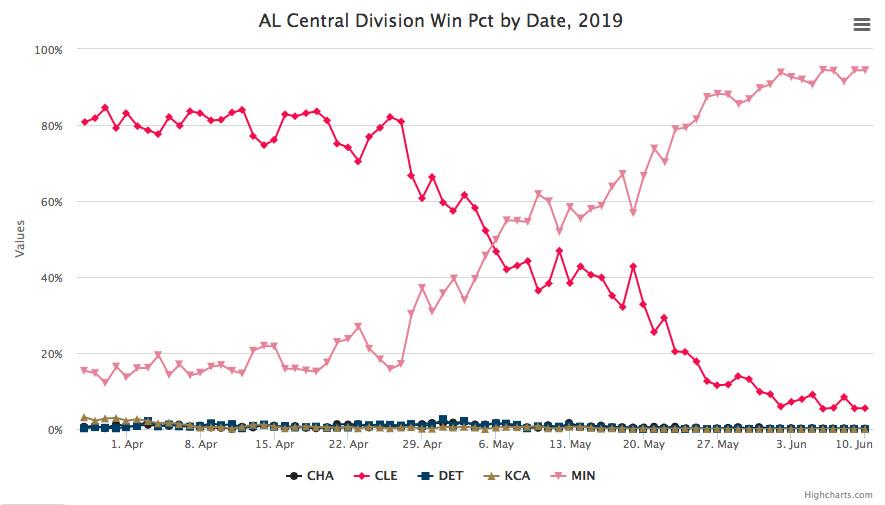

Here’s a graph of the five AL Central teams’ odds of winning the division, according to BP, with Cleveland’s in red and Minnesota’s in pink.

In just 11 weeks, Cleveland has gone from a 1-to-4 favorite to win the AL Central to a 19-to-1 long shot. They’re still very much alive in the wild-card race, and with only one team in front of them, even a 10.5-game deficit in the division is not insurmountable this early in the season. But the expected cake walk has turned into a death march.

Even at their best, the Indians are a bit of a high-wire act. Cleveland, which hasn’t run a payroll above the MLB median since 2002, is very good at acquiring and developing talented players. Of their top 11 players in bWAR last year, only Francisco Lindor, Jason Kipnis, and José Ramírez had played their entire professional careers in the Indians’ system, but nine of those 11 (essentially everyone except Edwin Encarnación and Yonder Alonso) experienced their first professional success in an Indians uniform.

Cleveland’s core is essentially made of six players: Lindor, Ramírez, and pitchers Corey Kluber, Mike Clevinger, Trevor Bauer, and Carlos Carrasco. Lindor and Ramírez were both worth 7.9 bWAR in 2018, while the four starting pitchers made up the bulk of what was probably baseball’s best rotation. Last year, 13 starting pitchers threw 175 or more innings with an ERA+ of 125 or better. Four of them played for Cleveland.

The Indians’ best six players compare favorably to any other team’s. But their weakness is in roster spots seven through 25. The three best teams in the American League last year—New York, Boston, and Houston—have combined cutting-edge recruitment and development strategies with big-market brute force to build up tremendous depth. Each club produced at least one MVP-caliber player from its own farm system then filled out the rest of the roster with a combination of homegrown role players and established stars acquired through trade or free agency.

Cleveland, by contrast, has cried poor and relied on manager Terry Francona, one of the game’s top tacticians, to deploy a bargain-basement supporting cast in the optimal fashion. Their CEO, Paul Dolan, runs the team like he’s trying to activate an escape clause in the team’s stadium lease. Being the cousin of embattled Knicks owner James Dolan isn’t the most damning thing about the Indians’ controlling owner. Some 18 months ago, Dolan reluctantly gave up the fight to keep Cleveland’s former racist logo. This came after four years of the team claiming it was phasing Chief Wahoo out while wearing its putative “alternate” cap every time it played on national TV. Dolan called getting rid of Chief Wahoo “the hardest decision we’ve had to make during our entire ownership,” which is certainly telling, if not sympathy inducing.

This offseason, Dolan oversaw a $15 million reduction in spending on MLB player salaries—11 percent of the club’s 2018 Opening Day payroll. Encarnación, Josh Donaldson, Alonso, Andrew Miller, Michael Brantley, Cody Allen, Yan Gomes, and Yandy Díaz were all either traded or allowed to walk as free agents. The only big-name player Cleveland acquired was Carlos Santana, who at this stage in his career is more of a salary makeweight than a foundational major league contributor.

Cleveland also shopped Kluber and Bauer this offseason, as their salaries ($17.2 million and $13 million, respectively), while about half the going rate for a Cy Young–quality pitcher, were getting too rich for Dolan’s liking. In a March interview with Zack Meisel of The Athletic, Dolan essentially promised that the team would not make a serious attempt to re-sign Lindor, its franchise player, before he hits free agency in three years. Furthermore, Cleveland will not pursue top-end free agents, even as the market for such players hit and then fell through rock bottom in the past three years.

It might not be fair to blame all of Cleveland’s struggles on Dolan, because as the Indians themselves have demonstrated, it’s possible to build a winning roster in this fashion, and Cleveland has invested in established players via trade (Miller in 2016 and fellow lefty relief ace Brad Hand in 2018) and, in the case of Encarnación and Alonso, free agency. It’s somewhat risible that the three-year, $60 million deal Encarnación signed before the 2017 season is Cleveland’s franchise record and that they traded Encarnación before the deal was up, but the Indians did nonetheless hand out a franchise-record contract in recent memory.

But a team that operates on the cheap to this extent has very, very little room for error. Houston, New York, and Boston all built homegrown cores comparable to Cleveland’s. But all three of those clubs have locked up at least some of their star players long term and supplemented them with reliable veterans acquired through trade or free agency.

The 2019 Indians have been catastrophically unlucky. Of their six key players, only Bauer has been healthy and effective all year, and even he’s taken a bit of a step back. Clevinger has missed two months with a back injury, while Kluber took a line drive off his pitching arm in May and won’t return until at least August. Lindor missed most of April with a calf strain, and Carrasco is out indefinitely with a “blood condition,” which is as scary as it is bizarre. Ramírez has been in the lineup almost every day, but is hitting .200/.295/.296.

The Yankees have suffered catastrophically bad injury luck, and the Astros—who are currently without José Altuve, Carlos Correa, and George Springer—have taken a beating as well. But both of those teams, unlike Cleveland, built up the depth necessary to weather these bumps in the road, and both remain near-locks to make the postseason, as they were on Opening Day.

Dolan argued that the Indians can’t afford to keep their own top-end players, let alone sign more, because the team can’t afford to commit $30 million a year to one player and still field a competitive roster. It’s not just about keeping Lindor or Bauer, who will be a free agent after next season, or bringing in a Bryce Harper or a Manny Machado off the open market. The Indians’ lack of spending takes them out of the running for the kind of solid complementary players on whose backs successful teams are built.

According to Cot’s Contracts, the Astros are paying 17 players more than $3 million this year, including Brantley, who has 28 extra-base hits this year. (Cleveland’s three starting outfielders, Jake Bauers, Leonys Martín, and Tyler Naquin, have 38 extra-base hits combined.) The Yankees are paying 16 players more than $3 million. The Indians are paying just 10 players more than $3 million, including Danny Salazar, who hasn’t thrown a big league pitch since 2017. Obviously, Cleveland is operating with a smaller budget than the Yankees, but just across the way in Milwaukee, the Brewers have constructed a sustainable contender by spending prudently, if not lavishly, on free agents like Lorenzo Cain, Yasmani Grandal, and Mike Moustakas. No matter the team’s budget, free agency is a buyer’s market now. All it takes is the will to buy.

When the Astros or Yankees lose a key player, they have competent big leaguers to take his spot in the lineup. The Indians, on the other hand, have just been adding more minor league free agents and waiver wire pickups to a 25-man roster that had too many of those to start. The Indians aren’t even paying a player $20 million this year (the Mariners are paying a portion of Santana’s salary), and already their roster is paper thin.

Some of those minimum-salary callups have been quite good, such as pitchers Shane Bieber and Zach Plesac, but the three-team trade that sent Encarnación and Díaz out in exchange for Bauers and Santana last December looks like a disaster; Santana (139 OPS+) is more or less holding serve with Encarnación (140 OPS+), but Díaz (124 OPS+) is badly outproducing Bauers (72 OPS+). Hand is pitching well, but there’s a non-trivial chance the catching prospect Cleveland traded to get him, Francisco Mejía, will come back to bite the franchise. Cleveland was a 90- or 100-win team when its core was healthy and its front office was winning every trade. Now that the team’s dealing with so many injuries and making a few personnel mistakes to boot, Cleveland is lucky to be a .500 team.

The Indians are only two games out of the second wild-card spot, so they aren’t in a position to completely write off 2019. Clevinger will be back soon, and if the Indians can hang around with Boston until August, they could go into the stretch run with most of their rotation intact and become a truly terrifying opponent in a one-game playoff. But the trade rumors around Bauer are heating up again, and teams in need of bullpen help are eyeing Hand.

Weirdly, the thin roster that got the Indians into this position might be the best argument for the Indians to stay the course, because unless they’re going to trade Lindor, there isn’t much else of value to sell. Kluber, who’s 33, is under team control through 2021, as is Lindor, who ought to expect something like Nolan Arenado’s eight-year, $260 million deal for his next contract, and Dolan’s made it clear Cleveland won’t offer such a deal.

That means Cleveland either has to win big in the next three years or try to turn its existing roster into players who can be as good in the future as Kluber and Lindor are now, which is a tall order. If Cleveland isn’t going to pull the plug on the entire core, it’s unlikely that the teams that might be interested in Bauer and Hand would give up players with equivalent or better short-term big league potential.

Riding out the 2019 season and then running it back next year might seem like an unsatisfying response to an unsatisfying first half, but it’s probably the best option. Well, apart from paying to build a deeper roster, but that might not be an option.