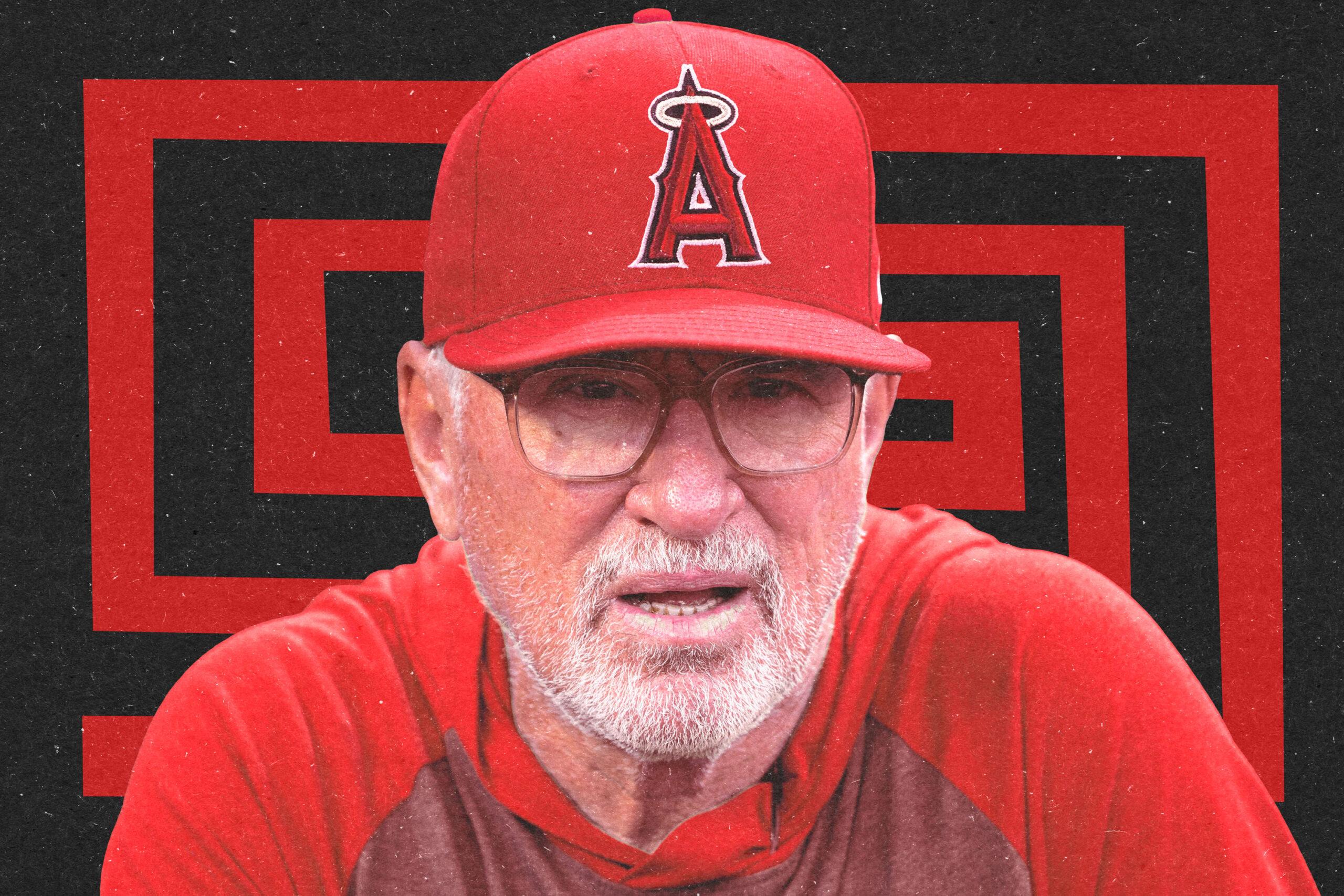

Joe Maddon Was the Obvious Hire for the Angels. Is He the Right Man for the Job?

Maddon taking over as manager in Los Angeles represents a homecoming. It’s more than just another rebuilding situation, though—and his past struggles dealing with a sensitive situation could become increasingly relevant.

Joe Maddon is coming home. Before he made his name as manager of the Rays and Cubs, Maddon was an Angels lifer. He joined the organization as a minor league catcher in 1976 and remained with the team long after his retirement in 1979. Over 31 years with the Angels, Maddon worked as a minor league manager, minor league coach, player development coach, scout, and finally a big league coach who remained on staff for more than a decade as the club cycled through managers (Buck Rodgers, Marcel Lachemann, Terry Collins, Mike Scioscia) and location names (California, Anaheim, Los Angeles of Anaheim). Maddon was Scioscia’s bench coach when the team won the 2002 World Series, and he even spent two spells as the club’s interim manager.

Now the 65-year-old three-time manager of the year has the job on a full-time basis, as he signed a three-year contract on Wednesday to return to the club. This reunion makes so much sense, for both Maddon and the Angels, that the actual announcement feels like a formality; it’s been blindingly obvious that Maddon would return to Orange County since the moment he left the Cubs on September 29 and the Angels fired incumbent skipper Brad Ausmus a day later. It’s an obvious move, but it also comes as the Angels face a perilous stretch—one Maddon might be ill-suited to navigate.

A few years ago, front offices began to hire managers from a pool of inexperienced, recently retired pros, rather than from the group of seasoned coaches who cut their teeth in the minor leagues. We’re past the peak of that trend, but the Angels’ organizational love of superstar managers (they famously endowed Scioscia with a 10-year, $50 million contract that expired in 2018) makes them a rarity in this day and age. And there’s no bigger superstar among managers than Maddon, who made waves after earning the Tampa Bay job in 2006 by combining his vast experience with a willingness to integrate empirically proven strategies handed down by his front office. In 2008, as he led the hitherto snakebit Rays to the American League pennant, Maddon’s trendy glasses stood out among a group of managers that still included Bobby Cox and Tony La Russa, men whose station in an MLB dugout by that point would have rankled Indiana Jones.

Throughout his career, Maddon has won over players with his enthusiasm—when the Cubs were winning, it seemed like they threw a costume party every time they boarded the team plane—and laid-back style in the clubhouse. He’s won over local media by becoming baseball’s most erudite manager, a folksy yet professorial type who will meet strangers with a smile and give expansive answers to simple questions. And he’s won over his bosses and fans because, well, he’s won—in 14 full seasons as a manager, Maddon’s teams won 90-plus games nine times, went to the playoffs eight times, and won two pennants and a World Series.

But while hiring Maddon was one of the most important signposts in the Cubs’ rebuild under Theo Epstein and Jed Hoyer, the manager and the front office quickly began to chafe when the positive results stopped coming. After the Cubs tumbled from world champion in 2016 to division champion in 2017 to wild-card contestant in 2018 to missing the playoffs altogether in 2019, Epstein and his confreres decided to find a new field boss.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that time is up on Maddon as a good MLB manager. He’s a rah-rah guy, after all, and even good rah-rah acts go stale after a while. Maddon’s Cubs still went 84-78 this year; the Angels finished 72-90 and have now managed to convert seven years of having the best player in baseball history into precisely zero playoff wins. If Maddon got the Angels to a point where winning 84 games was a fireable offense, they’d build a statue of him outside the ballpark. Plus he has experience managing rebuilding teams: the Rays and Cubs were coming off 95- and 89-loss seasons, respectively, when he took over, and we saw how quickly he turned things around.

At 65, though, Maddon is not a young man, and the next generation of smart young managers—like A.J. Hinch, Craig Counsell, and Dave Roberts—is starting to pass him by. Maddon’s return to Orange County is like former Georgia coach Mark Richt’s return to Miami: part reclamation project for a team that had lost its rudder, part victory lap for a beloved son.

But the greatest issue facing the Angels has nothing to do with on-field performance. On July 1, 27-year-old pitcher Tyler Skaggs was found dead in his hotel room while the team was in Texas on a road trip. Two months later, the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Office reported that Skaggs had died by choking on his own vomit, and that he had fentanyl, oxycodone, and alcohol in his system, prompting the DEA to launch an investigation. Last Saturday, ESPN’s T.J. Quinn reported that Angels communications director Eric Kay had told the DEA that he’d habitually supplied Skaggs with oxycodone, and that the two had used opioids together. Furthermore, Kay said that in 2017 he’d reported Skaggs’s drug use to his supervisor at the time, Tim Mead, who was then the club’s vice president of communications but has since left to run the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Skaggs’s family has retained high-profile attorney Rusty Hardin and seems likely to file a wrongful death lawsuit against the Angels. The Los Angeles Times has also reported that the DEA has questioned six other Angels players as part of its investigation into Skaggs’s death.

This story is heartbreaking on several levels, from the grief over the death of a beloved young ballplayer who was an emerging leader in the Angels clubhouse, to the insidious grip of substance use disorder, to the window it provides into the national opioid epidemic, to the constant looming specter of a sports culture that requires athletes to play through pain but frequently does not provide adequate resources to help them manage it safely. It is also important from a legal and criminal perspective, as MLB will have to react eventually if investigations determine that there’s an opioid epidemic within the sport. Though given the league’s past history of dealing with drug use among players, from cocaine in the 1980s to PEDs at the turn of the century, it’s reasonable to fear that its response will be draconian and punitive rather than empathic and restorative.

This developing scandal will also define the Angels’ 2020 season. Not just because lawyers and federal agents will be swirling around the club like leaves in the wind, but because the players are still recovering from Skaggs’s sudden death. Helping to facilitate that recovery will be a large part of Maddon’s brief in his first season at the helm.

Baseball managers are not social workers or lawyers or counselors, and it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to appreciate the difficulty and awkwardness a manager faces when he’s used to answering questions about bunting or bullpen management and suddenly has to take on serious issues that pervade society at large, and have life-or-death consequences. For good or ill, though, we have some evidence as to how Maddon approaches those kinds of questions. Late in the 2018 season, MLB placed Cubs shortstop Addison Russell on administrative leave and later suspended him after his ex-wife, Melisa Reidy, wrote a blog post detailing physical and emotional abuse she said she’d suffered in their relationship. After Russell was put on administrative league, Maddon was asked about the situation in a radio interview and said that he had no interest in reading Reidy’s account. “Anybody can write anything they want these days with social media, blogging, etc.,” Maddon said. “So I’m just going to wait for it to play its course, and then I’ll try to disseminate the information based on both sides, MLB itself, along with the players’ union and getting together with Addison and his former wife, and then I’ll read the information to try to form my own opinions.”

Four days later, after Epstein had commented on the situation and called Reidy’s account “disturbing,” Maddon said, “I really don’t understand why I have to become more involved than that.”

It was—and is—disappointing that a manager who’d been defined by his garrulous manner with the press would give such flippant and callous answers when confronted with such an important topic. Domestic violence is a nationwide public health crisis, and MLB—like every major sports organization—is in the throes of a very messy, very public reckoning over how best to confront it. If the first trickles of information coming out about opioid misuse on the Angels are any indication, another reckoning is coming, and Maddon, by virtue of his office, will once again be at the center of the discourse.

The hope is that Maddon has learned from the mistakes he made in handling the Russell situation, and that he’ll approach the questioning over the Skaggs investigation and possible future lawsuit in a more thoughtful and compassionate manner. It’s important that he does, not just for the purposes of helping his team weather a public relations nightmare, but because this story is a profound human tragedy and deserves to be discussed with gravity and care. It might not have much to do with baseball as such, and it certainly won’t be the most comfortable part of his job, but it’s the most important thing Maddon will do in the coming year. If he hasn’t learned his lesson, it won’t matter much where the Angels finish in the standings.