Squint at this season’s stats in Major League Baseball, and the beginnings of a bullpen course correction become clear. For the fourth consecutive year and the sixth in the past seven, relievers are consuming a bigger piece of the overall-innings pie, racking up a record 39 percent of pitchers’ leaguewide workload. In part, that’s because the number of relievers used per team per game is also on the rise, reaching a record 3.3 after a fifth consecutive annual increase. But there’s slightly more to the story: After decades of ever-more-delicate care, relievers have also been lasting a little longer once they’re in the game.

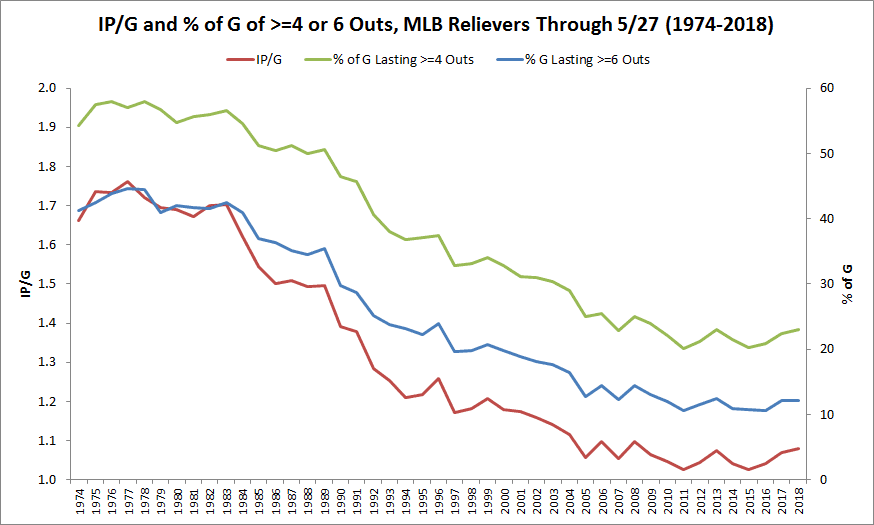

Through Sunday, the average number of innings pitched per relief appearance, 1.08, had bounced back to its highest level since 2008. The percentage of relief outings lasting at least four outs or six outs—23.0 percent and 12.2 percent, respectively—were at their highest levels since 2013 (and before that, 2009). At the very least, we’ve reached a bullpen plateau, the point at which managers have stopped reining in relievers more strictly with each successive season. And it’s looking like the long-term trend toward shorter relief outings is starting to reverse itself, even if, as the below graph of reliever usage through May 27 of every season since 1974 (the first for which complete play-by-play data is available) shows, the league as a whole is still nowhere near 20th-century norms.

Those tiny 2018 upticks are partly attributable to one pitcher whose usage and success stand out from the bullpen pack: Josh Hader, the Brewers’ bullpen beast, who’s been both a throwback to yesteryear’s relievers and a flash-forward to a future hitter’s hellscape. Hader, a 24-year-old lefty in his sophomore season, is the most dominant member of a Brewers bullpen that has helped the team to the best record in the National League. Brewers relievers lead the majors in WAR,win probability added, park-adjusted ERA, and groundball rate and trail only the Yankees in strikeout rate, so being the best of that bunch is a notable achievement. Even so, that distinction undersells him: Thus far, the southpaw has been the most dominant member of any bullpen in baseball, in this or any year. Hader is doing things on a per-batter basis that haven’t been done, and, thanks to his 1970s-style usage, he’s also making a run at a seemingly unassailable reliever record that’s stood for 54 seasons.

When Hader has thrown a pitch in the strike zone, hitters have made contact only 61.4 percent of the time. That would be the best rate on record. He’s struck out 62 batters, or 57 percent of the opponents he’s faced, which would also be a best-ever rate with room to spare; only Aroldis Chapman in 2014 and Craig Kimbrel in 2012 have reached 50 percent before. His 1.15 ERA is higher than his 0.94 FIP; park-adjust that bad boy and it ranks third all time, after Eric Gagne’s Cy Young–winning 2003 and that high-strikeout season by Kimbrel. Lefties have managed a .229 OPS against him, and regardless of handedness, hitters he’s gotten to two strikes against have gone 1-for-78. On the rare occasions when hitters have made contact, they haven’t hit the ball hard; Hader’s average exit speed allowed sits in the slowest 20 among the 430-plus pitchers with at least 25 batted balls allowed. In fact, he’s hit the ball harder himself than the hitters who’ve faced him have: He’s 1-for-1 at the plate with a single off the Cubs’ Kyle Hendricks that left Hader’s bat at 95 mph.

But it’s not just the quality of Hader’s work that has earned him early awards buzz: It’s the quantity, too. Hader has pitched at least two innings in each of his past four outings and seven of his past eight; in the first of those games, he went 2 2/3 in the longest-ever outing in which every out was recorded via Ks. Only once this season has Hader gotten into a game and failed to whiff more than one batter. All told, Hader has thrown 31 1/3 innings in 18 appearances, or 1.7 innings per game. Only two relievers in the past 25 years have combined durability and dominance by averaging that many innings per appearance while recording a FIP below three: Scot Shields in 2004 and Mariano Rivera in 1996.

This year, Hader has entered as early as the fourth inning and as late as the 10th. Everything written about Andrew Miller’s reshaping of relief roles since he was traded to Cleveland in 2016 pertains to Hader, too; in almost every way, he’s more extreme than Miller. Like Miller, Hader was once a starter. Drafted by the Orioles in 2012, traded to Houston in 2013, and then regifted to Milwaukee two years later in the Carlos Gómez–Mike Fiers swap (one that the Astros would probably like back, not that they’re short on pitching), Hader ranked in the 30s on last spring’s Baseball America and MLB.com top-prospect lists despite long-standing concerns among scouts that shaky command and insufficient secondary stuff would relegate him to relief. Those projections proved prescient last June, when he switched from a starting gig in Triple-A to a bullpen job in the bigs.

At the time, Hader hadn’t pitched in relief since a stint in the 2015 Arizona Fall League, but he didn’t mind being accommodating if it meant an expedited trip to the majors, and he hasn’t objected to staying in the pen in the year or so since. “I’ve just always been open to everything,” Hader says via phone. “Obviously being in the bullpen is a new thing to me, but pitching isn’t.” Hader’s do-anything ethos extends to his uniform number; although he wore 17 prior to his promotion, that number is quasi-retired by the Brewers, for whom Jim Gantner once wore it. Hader didn’t care; instead of 17, he donned the not-so-storied 71, which no player has ever worn in the majors for more than a four-year period. Nor does he have any qualms about when he comes into games or how long he remains on the mound. “You just attack hitters, and when it’s over, it’s over,” he says. Some pitchers get accused of overthinking things on the mound, but Hader won’t be one of them.

Even though Hader hasn’t pitched since Friday—he was warming on Monday until a seventh-inning bomb by the Brewers’ Jonathan Villar put the game out of reach and sat him back down—he’s on pace for 183 strikeouts, which would snap the single-season reliever record of 181 recorded by Boston’s Dick Radatz in 1964. Radatz, aptly nicknamed “The Monster,” was then at the end of the most valuable three-season stretch a reliever has ever had. From his ’62 rookie season through ’64, Radatz threw 414 innings without making a single start, amassing more WAR than any pitcher except Hall of Famers Sandy Koufax, Juan Marichal, and Don Drysdale. He also struck out 29.0 percent of the hitters he faced over that span, in an environment where the leaguewide rate was only 15.0 percent. Radatz was so overpowering and prolific that his best two seasons by WAR would tie for eighth on the table below.

Highest Pitching WAR in 3-Season Stretch, 0 GS

Hader isn’t going to get anywhere close to Radatz’s 157 innings in that record-setting season, which is probably for the best: Likely as a result of his heavy workloads, Radatz pitched at a sub-replacement level for five more injury- and control-problem-plagued years and was done at 32. Aside from the obvious safety considerations and the need to save his arm for a possible postseason run, Hader will have to fight for as many innings in manager Craig Counsell’s strong pen: Closer Corey Knebel and fellow lefty Boone Logan have recently returned to the fold, and Jeremy Jeffress, Matt Albers, Jacob Barnes, and others give the Brewers rival late-inning options. Hader’s best hope of breaking Radatz’s record lies in continuing to strike out opponents at an unprecedented rate, and he appears perfectly equipped to do that.

Clearly, Hader has good stuff: His fastball averages almost 95 mph, and among the nearly 300 pitchers with at least 20 innings pitched this season, only five boast more combined horizontal and vertical fastball movement. Hader has also at least temporarily retired the middling changeup that he used sporadically last season, instead supplementing his heater with an improved slider that he says he’s refined to the point “where my hand’s behind the ball and I’m getting around over the top of it.” Experience has taught Hader how to place the pitch where he wants. Last year, his average slider came in 2 feet above home plate, more than an inch above the league-average slider; this year, it’s coming in about 5 inches lower, more than 3 inches below the average pitcher’s. Even a choked-up Joey Votto in contact mode isn’t immune to the low slider’s appeal.

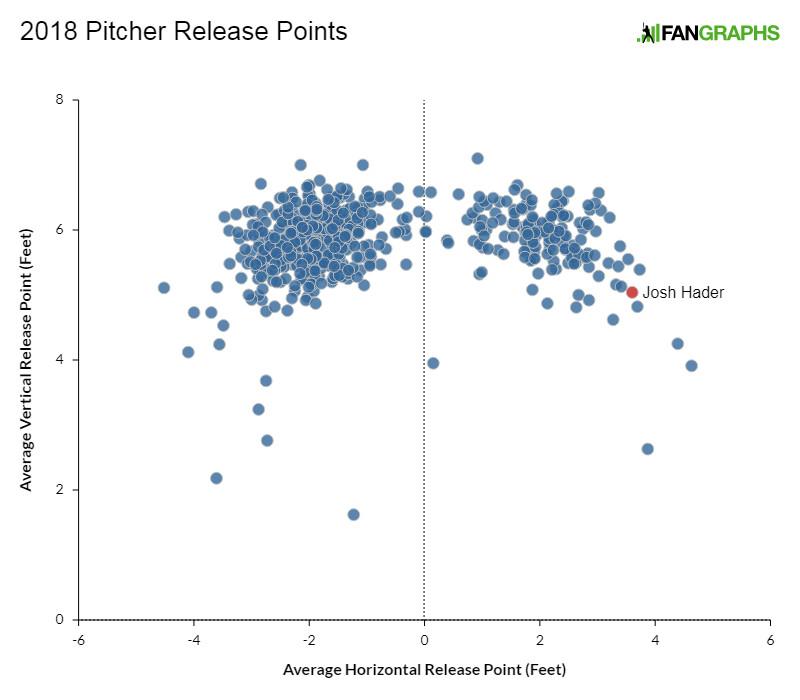

But there’s more than speed, movement, and plate location behind Hader’s unhittability. “Obviously the deception’s there, and that’s one of the things that helps me a lot, is these guys pick up the ball kind of late off me,” he says. Hader, who stands on the left side of the rubber and has released the ball even farther toward the first-base side this season than he did in 2017, throws across his body from a low arm slot that makes his pitches’ typical point of origin among the most extreme in the majors. The following chart shows every pitcher’s average release point this season. Hader’s dot is in red, 3.4 inches to the left of and 1.4 inches lower than that of Chris Sale, another lefty with a weird-looking delivery whom scouts have long cited as a mechanical comp for Hader.

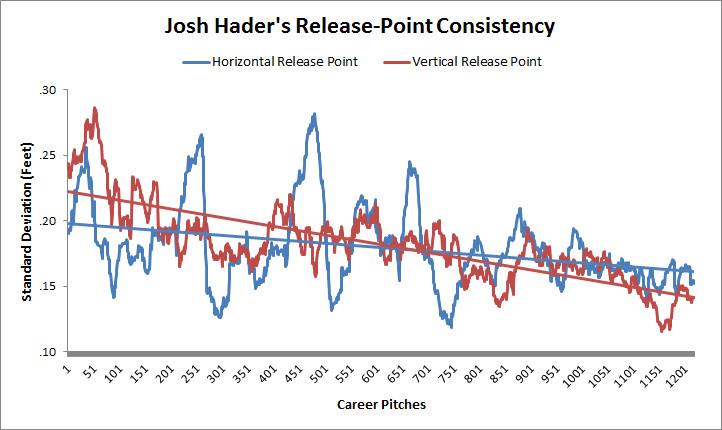

Hader, for his part, admits to admiring Randy Johnson but says he hasn’t modeled himself on any other pitcher. Nor does he think his pitching approach strongly resembles anyone else’s in the majors today. (His stats support that statement.) In addition to throwing the ball from an unusual slot, he turns his back to the hitter, hiding the ball for as long as possible. With time and effort, he’s also made major strides in releasing the ball from the same spot and, he says, “being able to go down the mound instead of east-west with my body,” which was a challenge because of all the moving parts before the pitch. In the course of our 10-minute conversation late last week, Hader said “consistent” or “consistency” 10 times. (Once, in fact, he said “consistent consistency.”) Although “consistency” can be the kind of cliché that Joe Morgan might use, in Hader’s case it’s not a nothing word. The graph below shows (deep breath) the 50-pitch rolling averages of the standard deviations of his horizontal and vertical release points (exhale) since he made the majors—essentially, a measure of how tightly clustered together his release points have been over time. As the trend lines reveal, Hader has gradually gotten better at repeating his pitches, a process he expedited by ditching his windup over the winter—another Andrew Miller move—and pitching strictly from the stretch.

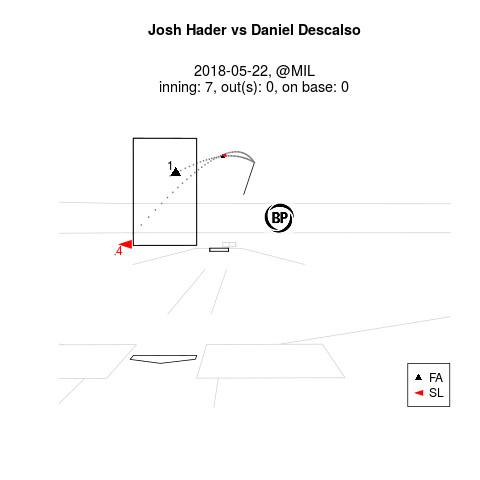

Thanks to that consistency, Hader has thrown more strikes and also become a master of tunneling, or delivering his pitches on such a narrow path to the plate that it’s difficult for the hitter to distinguish between different types. No pitcher who’s thrown as much as he has this year has posted a smaller average distance between back-to-back pitches at the point where the batter has to make a decision about whether to swing. Even his fastball-slider sequences evince an extraordinarily small distance between pitches from the batter’s point of view. “It helps when the fastball and the slider are in the same plane and they’re cutting different ways,” Hader says. Daniel Descalso could testify to that, as this GIF and its accompanying pitch plot (in which the fastball and slider seem to intersect) make clear.

Those three different layers of deception—uncommon release point, hidden ball, and tight tunnels—work in tandem to get tentative swings even when Hader doesn’t hit his spot.

When he does have everything working, goodnight nurse—or, in Hader’s most recent inning, goodnight Rosario, goodnight Nimmo, and goodnight Cabrera.

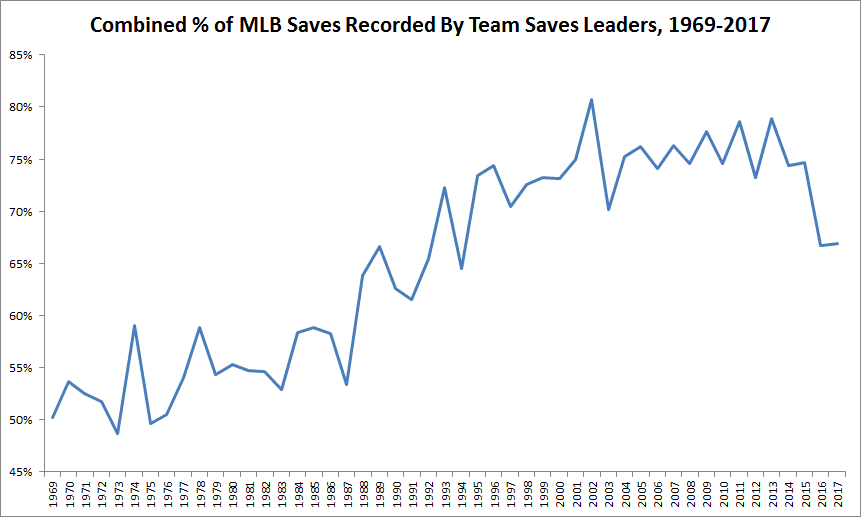

Hader’s game log isn’t the only indicator that we’re entering a renaissance period of open-minded and more malleable bullpen usage. Compared with just a few years ago, teams are spreading their saves around rather than giving them all to one guy.

Partly out of injury-related necessity, the Brewers have furthered that trend, too, featuring five relievers already with saves next to their names. But unleashing Hader has been their most exciting contribution to the cause. Now the key is keeping him healthy and resisting the urge to Radatz him right into an injury, which requires constant communication about how Hader is feeling. “Each day around the middle of the day, after I throw, I give [Counsell] a heads-up,” Hader says. “Obviously sometimes I’m feeling better than other days. It’s just reading the body, really. He ultimately makes the decision.” Counsell is comfortable with the decisions he’s made so far, and in light of both the Brewers’ and Hader’s strong starts, it’s hard to blame him: The Brewers are 18-0 in games Hader has pitched to this point.

Like Radatz, who initially expressed skepticism about pitching out of the pen but soon said, “I wouldn’t want to go back to being a starter,” Hader has taken to his current role. Radatz once finished fifth in MVP voting, and if Hader keeps up this pace, he’ll be among the top would-be award winners looking up at Max Scherzer in the NL Cy Young race. Someday his dominance might convince his team to try him in the rotation, but relocation likely won’t come at Hader’s request. “We’ll see when that time comes,” he says. “Right now I’m loving the bullpen and hoping I stay here.” The longer he records starteresque strikeout totals while working as a reliever, the more he’ll erode the distinction between the two roles.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of The Baseball Gauge and Rob McQuown and Martin Alonso of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.