I was standing in the Washington Nationals’ clubhouse, leaning against a wall and looking at my notebook, when I felt a gentle tap on my shoulder. I turned around to find the MLB leader in pitcher WAR, Gio González, standing behind me and leaning in with a look of great intensity in his eyes.

“Last thing,” he said. “Rendon should’ve made the All-Star team. He’s the best third baseman in baseball—the best.” Then he smiled, gave me a thumbs-up, and strolled around the corner to the players’ dining room.

I’d just finished interviewing the Nationals left-hander, a conversation in which—I realized later—he didn’t talk about himself for more than a sentence or two at any given stretch, but found time to praise 15 different teammates by name, plus pitching coach Mike Maddux. And while he was going about his routine after we’d talked, González came over to me three more times to single out teammates he’d forgotten to mention the first time around. No human interaction I’ve ever had has sounded so much like someone accepting a Grammy.

The way González is pitching, practicing an awards speech might be a good idea.

Washington catcher Matt Wieters is more than happy to talk about González. In his first season with Washington after a decade in the Orioles organization, Wieters quickly developed a rapport with the left-hander. Wieters had gotten to know both González and Max Scherzer when they were coming up through the minors, and played with both on American League All-Star teams. When the 31-year-old catcher arrived in Washington, the 31-year-old González made him feel at home.

“Gio is a very open and accepting person,” Wieters said. “He’ll open up his home and do anything he can to help.”

In return, Wieters has helped González, who turns 32 next month, to the best season of his career. González is allowing the fifth-lowest opponent batting average out of 63 qualified starters and the third-lowest ERA in the eighth-most innings. Mash all that together and he’s a fraction of a win ahead of Scherzer for the MLB WAR lead among pitchers at 6.6, which has already blown away his previous career high of 4.9, set in 2012, when he finished third in NL Cy Young voting.

Until this year, that 2012 season was the high-water mark of a career characterized more by consistency than spectacular performances. In 2004, the Chicago White Sox picked González 38th overall out of Monsignor Edward Pace High School in Miami Gardens, Florida, and then spent the next three years using him as a trade chip. After the 2005 season he was sent to the Phillies as part of a package for Jim Thome. The next year the Phillies sent him back to the White Sox as part of a package for Freddy García, and the year after that, the White Sox shipped him off to Oakland with two other players for Nick Swisher.

González registered his first 200-inning season in 2010, made the All-Star team in 2011, and at season’s end was himself the big name in a six-player trade that sent him to Washington. González is now the fourth-longest-tenured National, behind Ryan Zimmerman, Stephen Strasburg, and Jayson Werth, and in his first five full seasons with the club, he made between 27 and 32 starts, with a FIP between 2.82 and 3.76, a K/9 ratio between 8.7 and 9.3, and a BB/9 ratio between 3.0 and 3.5. In 2012, he led the National League in wins, K/9 ratio, FIP, and fewest home runs per nine innings, but apart from that, he hasn’t led the league in any major statistical category. In 2014, he missed about a month with shoulder inflammation, but otherwise he hasn’t suffered any major injury. He’s just been good, every fifth game, without much fuss. Since González arrived in Washington, only the Dodgers have won more games.

González doesn’t stand out in a rotation where Scherzer and Strasburg get most of the press. Compared to the broad-shouldered and intense Scherzer, the disconcertingly enormous Strasburg, and even the barrel-chested Tanner Roark, the 6-foot, 205-pound González looks almost frail.

Consequently, the Nationals’ only left-handed starter relies a little more on finesse than some of his teammates do. Though González worked his fastball up to around 94 miles per hour in 2012, his fastball and sinker both average close to 90 these days, giving him the eighth-slowest average heater of those 63 qualified starters.

“Gio’s been doing the same thing,” said Nats right-hander Edwin Jackson. “He pounds the strike zone, and his curveball is …”—here Jackson trailed off into several seconds of silence while making the face people make when they smell cookies baking—“… I need to learn that. His curveball is a great pitch, and he’s mixing it up well, and pitching with confidence.”

“He’s a lefty with a changeup he can use at any time, a fastball he can locate, and one of the best left-handed breaking balls in the game,” Wieters said.

It feels a little weird to talk about González as a command and control pitcher, because he has the 10th-highest walk rate among qualified starters, and only six qualified starters throw fewer pitches inside the strike zone. Since 2010, only Ubaldo Jiménez has walked more batters. That’s why ERA estimators—not just the relatively simplistic FIP but the cutting-edge DRA of Baseball Prospectus—think he’s outpitching his peripherals by more than a run. Rather than the most valuable pitcher in baseball, which is how Baseball-Reference WAR (based on runs allowed) rates him, BP ranks him 18th among starters, FanGraphs 21st—still very good, but not worthy of Cy Young consideration.

But while González works outside the strike zone, it’s not because he can’t hit his target. CSAA, a BP stat that works as a proxy for command, has González seventh among qualified starters. González, whose average fastball velocity is down 1.5 mph from last year, needs to be able to locate nowadays just to get by. He can work around the edges of the zone, and hitting his targets induces umpires to give him more borderline pitches, according to CSAA. It also confuses hitters—González is middle-of-the-pack when it comes to getting hitters to chase, but hitters swing at only 60.6 percent of his pitches inside the strike zone, the 10th-lowest rate among qualified starters.

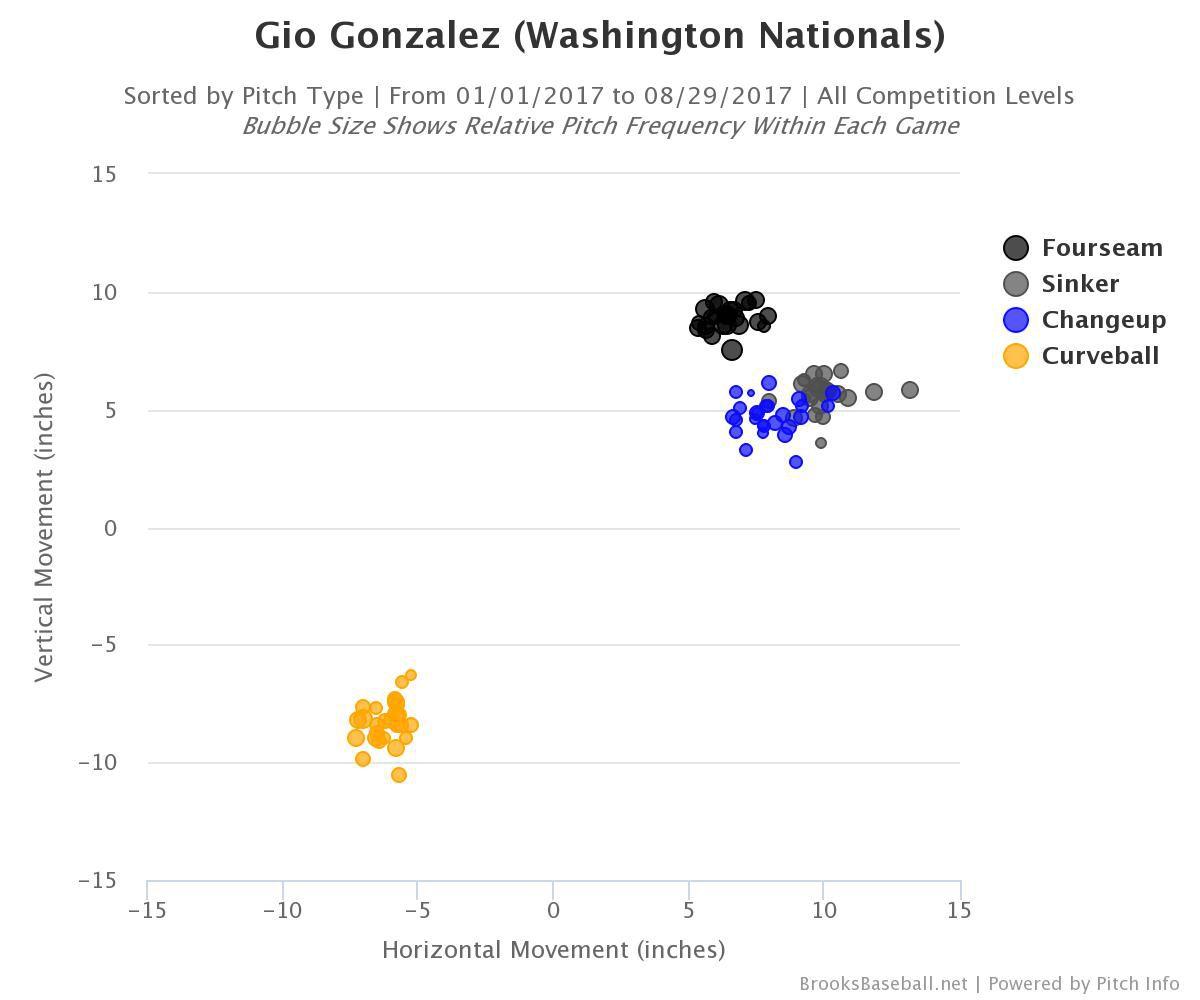

González works off a four-pitch mix: two fastballs (a four-seamer and a sinker), a changeup, and the curveball. With his reduced velocity, González is going off-speed a little less—about 57 percent hard stuff this year, compared to 65 percent last year—though both González and Wieters say that wasn’t part of any specific plan, just how things have worked out. Wieters says he’s throwing more changeups and curveballs this year simply because he’s commanding them so well.

“I think that’s what leads to him throwing more off-speed—he can throw it when he’s behind in the count, and it’s good enough to be a put-away pitch,” Wieters said. “But I also think he’s made a conscious effort to locate his fastball in on righties this year, which has helped open up the off-speed stuff a little more.”

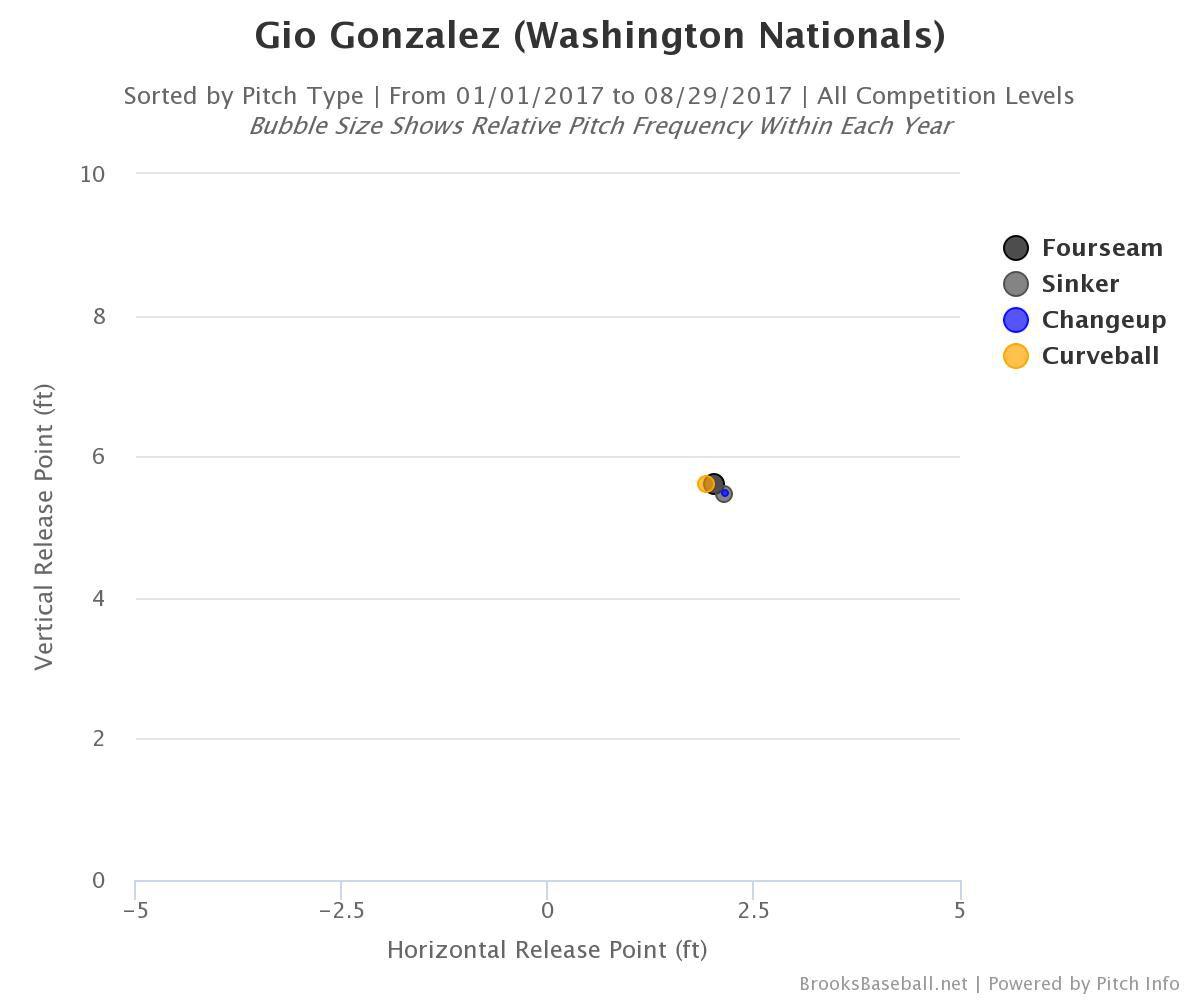

González’s pitches interact in a manner that’s pretty conventional but utterly devastating when he can command them. All four pitches look essentially the same coming out of his hand.

But they travel different paths once leaving it. His four-seamer runs up to his arm-side, while his sinker trades about a mile an hour’s worth of velocity for three or four inches’ more additional run. The changeup moves about the same as the sinker, but six miles per hour slower. All of those pitches bore in on left-handed batters, while his curveball starts to float up and in on lefties before falling out of the sky and across the plate. The difference between the sinker and the curveball is 14 miles per hour and more than 16 inches of horizontal break.

When you don’t know if a pitch is going to come up and in or turn around midflight like a boomerang, the effect on left-handed hitters is catastrophic.

“It’s a big one, but it’s a sharp one,” Wieters said. “It may look like a big, slow one on TV, but once it starts going down it keeps doing down. For him to be able to have the consistent spin on it has been impressive.”

González has about an even platoon split for his career, and in 2012 he actually ran a reverse split of about 100 points of OPS. This year, righties are hitting .215/.300/.364 off him, compared to a career line of .235/.319/.363. Lefties, however, are hitting just .162/.238/.201, for a .205 wOBA. That’s the lowest in baseball by 36 points, and about 200 points of OPS below his career average. Nine pitchers this year are slugging better than .201 in 50 or more plate appearances.

“A lot of left-handed hitters will be able to pick one side of the plate to hit on, and Gio likes to use the breaking ball on one side, then use the fastball to keep them from sitting on his breaking ball,” Wieters said. “His pitches play really well off of each other.”

González, of course, prefers to point to his batterymate.

“Wieters has to get all the credit in the world. He’s been doing great, helping me out as much as possible,” González said. “A lot of it’s been listening, mostly. I’ve gotten a lot of help from our pitching staff, some of the guys from the bullpen, and Matt and Mike [Maddux] have been fantastic.”

Although the relationship between Wieters and González involves a lot of communication, during the game itself Wieters pretty much calls the shots. He says González hardly ever shakes him off.

“Whatever Matt puts down, I feel like I’m attacking,” González said. “We actually have a game plan, not just going out there and trying to throw the baseball—we’re working.”

On July 31, González delivered his most notable performance of the year, when he took a no-hitter into the ninth against his hometown Marlins, on what would’ve been the 25th birthday of his friend and fellow Cuban American José Fernández. In eight-plus innings and 106 pitches, González said after the game that he shook off Wieters once.

“He gives you a lot of options as a catcher,” Wieters said. “He’s fun to work with. He goes out there and cares about the preparation he puts in, he cares about the work, and he cares about being out there and helping us win.”

That’s exactly what he’s done this year. Aside from a break for paternity leave when his second child was born earlier this month, González hasn’t missed a start. At no point this season has his ERA gone over 3.03, and the Nationals have won his past six starts, during a stretch when the Nats have been without Scherzer, Strasburg, and no. 5 starter Joe Ross at one time or another.

We ought to be talking about the season González is having, even if he’d rather talk about other people.