In August 2005, in the bowels of the Hyatt Regency in downtown Atlanta, the Rev. Jesse Jackson fumed. He couldn’t believe where his panel to discuss the pending expiration of key parts of the Voting Rights Act was being held.

Jackson surveyed the dozens of writers and broadcasters crammed into the small room, almost all of them there for the National Association of Black Journalists convention. Then he offered a stern warning. “To put this discussion in the corner of a basement is threatening to our survival,” Jackson said. “Out of the Voting Rights Act, we got affirmative action, [which led] … to your jobs.”

The crowd murmured in approval. He continued. “To put your own lifeline in the basement of your consciousness … is not a good thing.”

At that moment, Jackson’s words seemed hyperbolic. There had been little organized opposition to the Voting Rights Act in recent years, and Congress had overwhelmingly reauthorized and expanded it in 1982 and 1992 (and again in 2006, by a vote of 98-0 in the Senate). Nonetheless, Jackson was taking part in a “Keep the Vote Alive” campaign that included the panel (with the comedian and activist Dick Gregory and U.S. Rep. Artur Davis) and a rally in Atlanta the following day.

Jackson wasn’t taking anything for granted, and was shocked to learn that his panel had been moved to a small room at a conference at which former President Bill Clinton and the Rev. T.D. Jakes had spoken before thousands in significantly larger ballrooms. He encouraged the tiny room full of journalists to take his plea seriously.

“It’s been difficult to get the word out about the voting rights story, because I’ve had to go through a whole range of culturally insensitive [news executives] who never had to fight for the right to vote,” he said. “We were denied the right to vote for 346 years … and a group of enlightened Black journalists have just marginalized this discussion.”

Jackson had the discerning perspective of a man who grew up on the front lines of the Jim Crow South; he was inspired by the infamous Bloody Sunday march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, and later participated in the marches all across Alabama alongside Martin Luther King Jr. His words felt especially prescient in 2013, when the Supreme Court gutted parts of the law in the landmark Shelby County v. Holder decision. In one of his final public statements, Jackson wrote in 2021, “Every movement for equal justice under the law in this country has been met with a brutal reaction. … Once more people of conscience must stand up and organize to protect the right to vote and to counter those who would suppress it.”

It is a call and a cause that will now have to be answered by someone else. Jackson—the civil rights icon, pastor, and two-time Democratic presidential candidate—died Tuesday at his home in Chicago. He was 84.

Jackson was hospitalized in November for treatment of progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare neurological condition often mistaken for Parkinson’s disease, which he announced that he had in 2017. His family called for prayers at the time, signaling the severity of his illness. But he was released home two weeks later in “stable condition.”

“His unwavering commitment to justice, equality, and human rights helped shape a global movement for freedom and dignity,” his family said Tuesday in a statement announcing his death. “Our father was a servant leader—not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world. We shared him with the world, and in return, the world became part of our extended family. … We ask you to honor his memory by continuing the fight for the values he lived by.”

Congressman John Lewis, Congresswoman Maxine Waters, Harry Belafonte, Jesse Jackson, and Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi in August 2005

The end of Jackson’s life comes at a particularly fraught time for the country’s short-lived attempt at full multiracial democracy. Among the Trump administration’s attacks on civil rights since the president returned to the White House: announcing the end of all federal diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs; weakening enforcement against discrimination by ordering agencies to stop using disparate impact analysis; and dismantling civil rights offices in a number of agencies, including the Department of Education and the Social Security Administration. Trump himself has taken outsized interest in politicizing voting rights, saying recently “Republicans ought to nationalize the voting” and “should take over the voting in at least 15 places.” Under the Constitution, of course, the states—and not the federal government—have explicit authority over conducting elections.

These developments are the vestiges of the America that millions of Black people like Jackson were born into several generations ago. “Unfortunately, I think Rev. Jackson was prescient in many ways,” says ArCasia James-Gallaway, a professor at Texas A&M who authored a study on the 1970s push for desegregation in Texas schools. “My sense is that Black Boomers continue to maintain an acute understanding from an experiential level of what we risk if we take our eye off the ball of racial justice and assume we have arrived.”

Growing up in Greenville, South Carolina, Jackson was a standout student and athlete. He was the class president, a member of the National Honor Society, and the starting quarterback at Sterling High School. His athletic prowess earned him a scholarship to the University of Illinois in 1959, a ticket out of the South at a time when most of the nearby colleges were strictly segregated.

But according to Abby Phillip’s 2025 biography of Jackson, A Dream Deferred, the charismatic and self-assured Jackson felt “isolated and out of place almost from the moment he arrived” in Champaign. During the summer of 1960, back home in Greensville, Jackson—along with seven other Black students—protested the segregated library system, among several acts of civil disobedience. That July, Jackson and his friends were arrested after refusing orders from librarians and police to leave the library. They were charged with disorderly conduct and booked into the county jail, where a local attorney bailed them out after 15 minutes. “That’s how I lost my fear of death and jails,” Jackson told Phillip.

He was inspired, and he knew that he couldn’t return to Illinois. So Jackson transferred to North Carolina A&T, a historically Black college about 200 miles from his hometown.

At A&T, Jackson found himself in familiar leadership roles. He was elected student government president, and was again quarterback of the football team. But thanks to a nudge from school president Samuel DeWitt Proctor—himself a friend of King’s through their ties to Boston University—Jackson began to involve himself in the growing protest movement, on and off campus.

After graduating in 1964, inspired by King’s religious education, Jackson moved to Chicago to enroll in a graduate program at a seminary. But before long, he took King up on an offer to work as a full-time organizer. “You will learn more from working with me in six months than in six years at seminary,” King told him.

Jackson threw himself into King’s growing organization. He took on a role as a liaison between the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and organizers in Chicago, making a name for his ability to raise money and navigate the provincial nature of the city’s leaders. He made Chicago his home base, and would operate out of the city for most of the rest of his life. He also pursued other avenues for activism, including threatening boycotts of corporations that didn’t hire Black employees or subcontract with Black-owned companies. In 1966, Jackson’s first Operation Breadbasket campaign called for a boycott of a local dairy company for refusing his request to review its job rolls. He later arranged for picketers to march outside the stores of a grocery chain until it agreed to hire nearly 200 Black employees.

That work only accelerated after King was assassinated in 1968. “That’s when a new dimension of our struggle took off,” Jackson said in an interview in 2017. Jackson’s bold moves to assert himself as the successor to King’s legacy isolated him from a number of older civil rights leaders.

In an interview in 2000, the famed activist and minister Hosea Williams said he remained upset with Jackson for going on TV days after King’s killing in a shirt still smeared with his blood. “I went crazy. I really tried to kill Jesse,” Williams said. “I’ve never respected Jesse since that moment.”

Others were eager to embrace him as a leader, including the baseball legend Jackie Robinson, who called him “the next Martin Luther King Jr.” Only 26 when King died, Jackson wasn’t an obvious heir to lead the movement. He wasn’t a product of elite educational institutions like King, and he hadn’t been groomed for leadership like the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who’d served behind King as the second-in-command at the SCLC.

But Robinson, who had once inspired a teenage Jackson during an NAACP rally in Greenville in 1959, saw something profound in the charismatic upstart. In 1969, he touted Jackson’s promise during a SCLC demonstration in Springfield, Illinois.

“If some of us had the same courage as Jesse,” Robinson said, according to Phillip, “we wouldn’t be here today.”

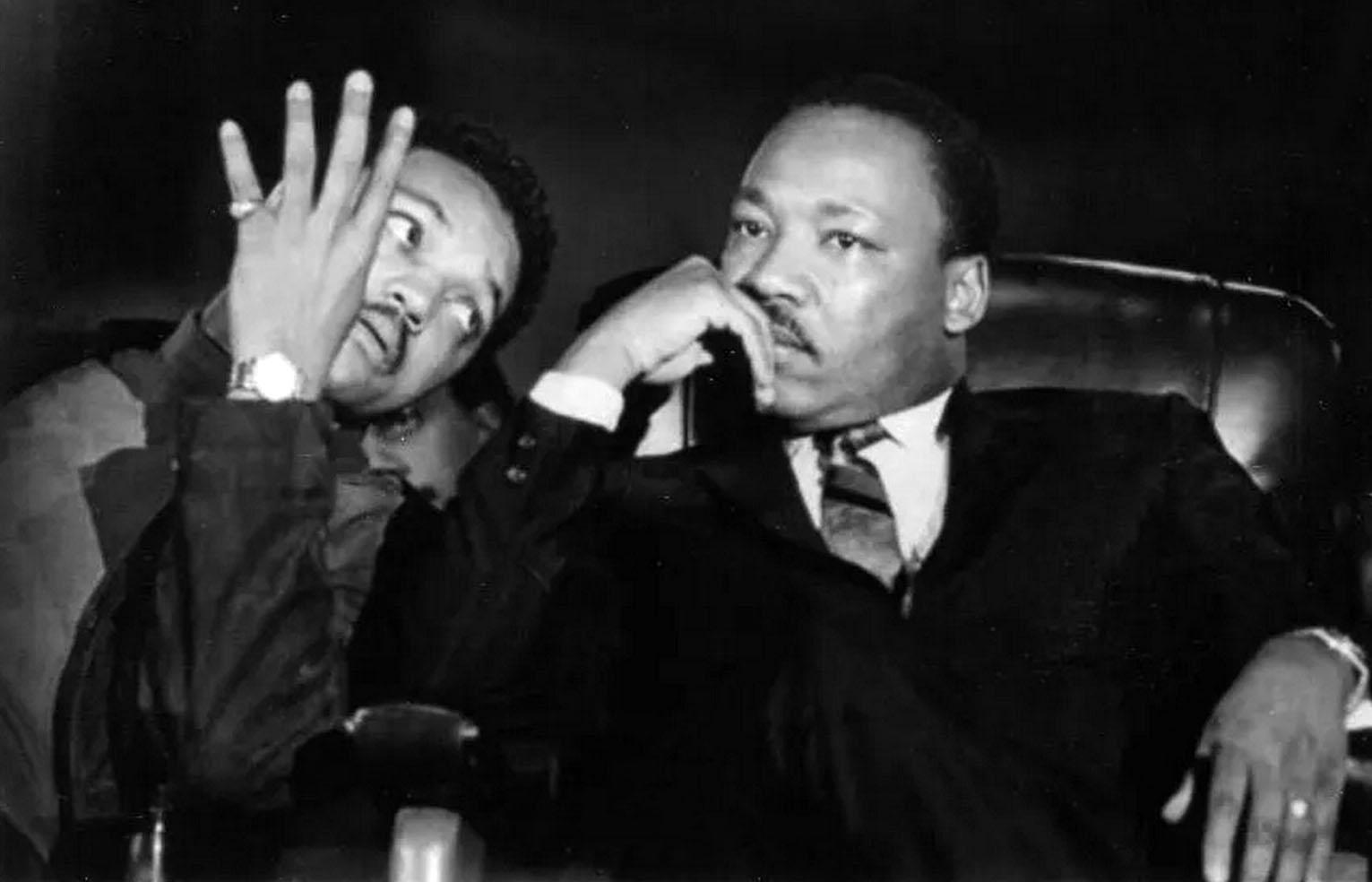

Jesse Jackson with Dr Martin Luther King in 1966

Jackson’s rise over the ensuing decades was undeniable. He used the power of activism to boost Black entrepreneurs and Black-owned businesses across Chicago. He argued vigorously that Black economic power was the key to gaining control of their communities. His organizations, Operation PUSH and PUSH Excel, sought to keep inner-city students in school and help them with jobs after graduation. He held rallies, trying to encourage students with his trademark motto: “Down with dope. Up with hope.”

By the 1980s, Jackson’s reach had extended far beyond Illinois, and he was one of the most influential Black men in America. He led boycotts against major companies including Anheuser-Busch, Coca-Cola, and Kentucky Fried Chicken over their lack of minority employees and distributors. He went to the Middle East and pushed for U.S. and Israeli acceptance of the Palestine Liberation Organization. He met with foreign leaders to secure the release of hostages in Syria, Cuba, and Iraq. And he was a leading voice in the global campaign to end apartheid in South Africa.

Jackson traded on his prominence to enter the arena of politics in 1983, becoming only the second Black candidate from a major party to run for president. After years of working mostly with Black supporters and in Black communities, he made clear in his campaign announcement that he sought to represent all marginalized groups. It was a multracial appeal that signaled a modest maturation of minority relations in America, a belief in politics that bound together voters by a number of considerations.

“This candidacy is not for Blacks only,” Jackson said. “This is a national campaign growing out of the Black experience and seen through the eyes of a Black perspective—which is the experience and perspective of the rejected. Because of this experience, I can empathize with the plight of Appalachia because I have known poverty. I know the pain of antisemitism because I have felt the humiliation of discrimination. I know firsthand the shame of bread lines and the horror of hopelessness and despair.”

With his unshakable confidence and swagger, Jackson attempted to organize a national political movement that would’ve seemed unthinkable a generation before. In a span of 20 years, Jackson had gone from risking his life to expand voting rights in South Carolina to winning delegates for the Democratic presidential nomination there.

“Jackson has gained so much power now that his use of it has become a critical factor in American politics,” the Washington Post columnist David Broder wrote in March 1984. “That could not have been said of any Black politician in the past.”

Jackson ultimately fell short, finishing third behind Senator Gary Hart of Colorado and former Vice President Walter Mondale, who went on to claim the Democratic nomination. Still, Jackson’s 50-minute “Rainbow Coalition” speech at the party’s convention in San Francisco articulated a vision of a more diverse coalition: “The desperate, the damned, the disinherited, the disrespected, and the despised.”

Mondale went on to lose in a landslide to incumbent President Ronald Reagan. The defeat was an ominous sign for Jackson and those who came out of the civil rights movement.

Reagan famously stood against Black advancement; he opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and once called for a return to “states’ rights” during a campaign speech near the Mississippi town where three civil rights activists were murdered by white supremacists in 1964. As president, Reagan opposed a national holiday honoring King, supported tax breaks for schools that discriminated on the basis of race, and opposed the extension of the Voting Rights Act, among other actions.

By the time Jackson launched his run to replace Reagan in the White House in 1988, he was considered one of the leading candidates in the Democratic primary. His team included more party insiders than it had four years earlier, and he filmed a campaign ad produced by Spike Lee, a sign of his increasing financial support. Jackson had broadening appeal, even as he sought to repair relations with Jewish voters after he used a slur in what he thought was an off-the-record interview on the campaign trail in 1984. (He later apologized for it.)

Jackson performed better this time, finishing first or second in 16 of 21 primaries and caucuses on Super Tuesday. But the nomination wasn’t to be; Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis won it and Jackson was again left to rally the party at its national convention, this time in Atlanta. He delivered, using his knack for powerful oratory to rouse the crowd and move many attendees to tears. He closed with words that would echo in future campaigns and movements for decades: “Keep hope alive!”

Jesse Jackson addresses the Democratic National Convention in 1988

That night in Atlanta may have been the high point of Jackson’s political career; the only election he’d ever win was the 1990 race for District of Columbia’s “shadow senator,” a position created by the city to lobby for its full representation in Congress. While that role had no voting power or formal authority, it gave Jackson access to the halls of power in Washington and some vestiges of his previous visibility.

His acolytes and protégés, including Donna Brazile and Ron Brown, moved on to positions in the DNC and Bill Clinton’s administration. Jackson returned to activism and social justice work through his National Rainbow Coalition organization, which later merged with Operation Push to become the Rainbow PUSH Coalition in 1996. And a younger generation of Black politicians rose to prominence in his wake—the likes of Barack Obama, Cory Booker, and Kamala Harris—who didn’t come out of the civil rights movement and spent much of their lives in integrated schools and workplaces. They were more accommodating to white grievances, and certainly much less incendiary in addressing racial discrimination.

Perhaps that approach was necessary to appeal to a broad base of voters in a nation not far removed from 1994’s “Republican Revolution,” a backlash to the rapid social and cultural changes of the previous decades. Jackson, ever the pragmatist, understood the need for moderation and even aligned himself closely with Clinton, a moderate Democrat who promised to “end welfare as we know it” and followed up with a spate of reforms that slashed welfare rolls but increased extreme poverty across the country.

Asked by former protégé Al Sharpton why he agreed to support Clinton, Jackson resorted to a football metaphor, according to A Dream Deferred. “We got to get as much as we can,” Jackson said. “Sometimes you got to gain yards. Let’s gain some yards, homeboy.”

I thought about that analogy when recalling the only time I ever met Jackson in person: at the 2007 funeral of Grambling’s Hall of Fame football coach Eddie Robinson. Jackson addressed the crowd of about 5,000 during the lively service, saying Robinson “was all of ours’ coach.”

At the end of the service, as Jackson cut a path out of Grambling’s new basketball arena, I stopped him for a brief interview and couldn’t help but notice how massive he was, standing about 6-foot-3 with hands the size of catcher’s mitts. It was easy to see where at least some of his charisma and confidence came from, given how much space he took up in any room. And even then, people were drawn to him in a room full of luminaries like the U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu and NFL Hall of Famers Willie Davis and Willie Brown.

I recalled a few months earlier, when Jackson was testifying before a House committee on the lack of diversity in college athletics leadership positions. He talked about the appeal of sports for Black Americans.

“Why are we so good at what is so hard to do?” he said, rhetorically. “Whenever the playing field is even, the rules are public, and the goals are clear, we do well.”

Jesse Jackson at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in 2016

Jackson’s faith in the ability of his people to do well was a large part of his life’s work. It’s why he continually challenged corporate leaders to diversify their boardrooms; why he threatened business leaders if they didn’t interact more with Black-owned firms; why he wanted to see voters elect more Black politicians. It’s why he found it so imperative to stress the importance of fighting to maintain voting rights on that August day in 2005—it pained him that the younger generation didn’t recognize the risk of losing the opportunity to compete.

I was a 27-year-old NABJ attendee on that day at the convention. I’m ashamed to say that I and many of the people who streamed out of that basement meeting room in Atlanta thought Jackson was being hysterical. It wasn’t uncommon for Black Boomers to be dismissed in this way, as they were time and again in the years to come.

“Their skepticism is well-earned in my opinion,” says James-Gallaway, who teamed with Fayetteville State University professor Francena Turner on a report about the history of Black Boomers. “They need to continuously see the proof.”

For as long as he was able, Jackson pushed America to show him the proof of its commitment to its promises. He started by asking his local library to let him borrow books like everyone else. He moved on to asking local businesses to hire Black workers. Then he asked the country to make good on its promise to treat Black Americans as equals, picking up that fight every chance he got.

Now, the fight is up to the rest of us.