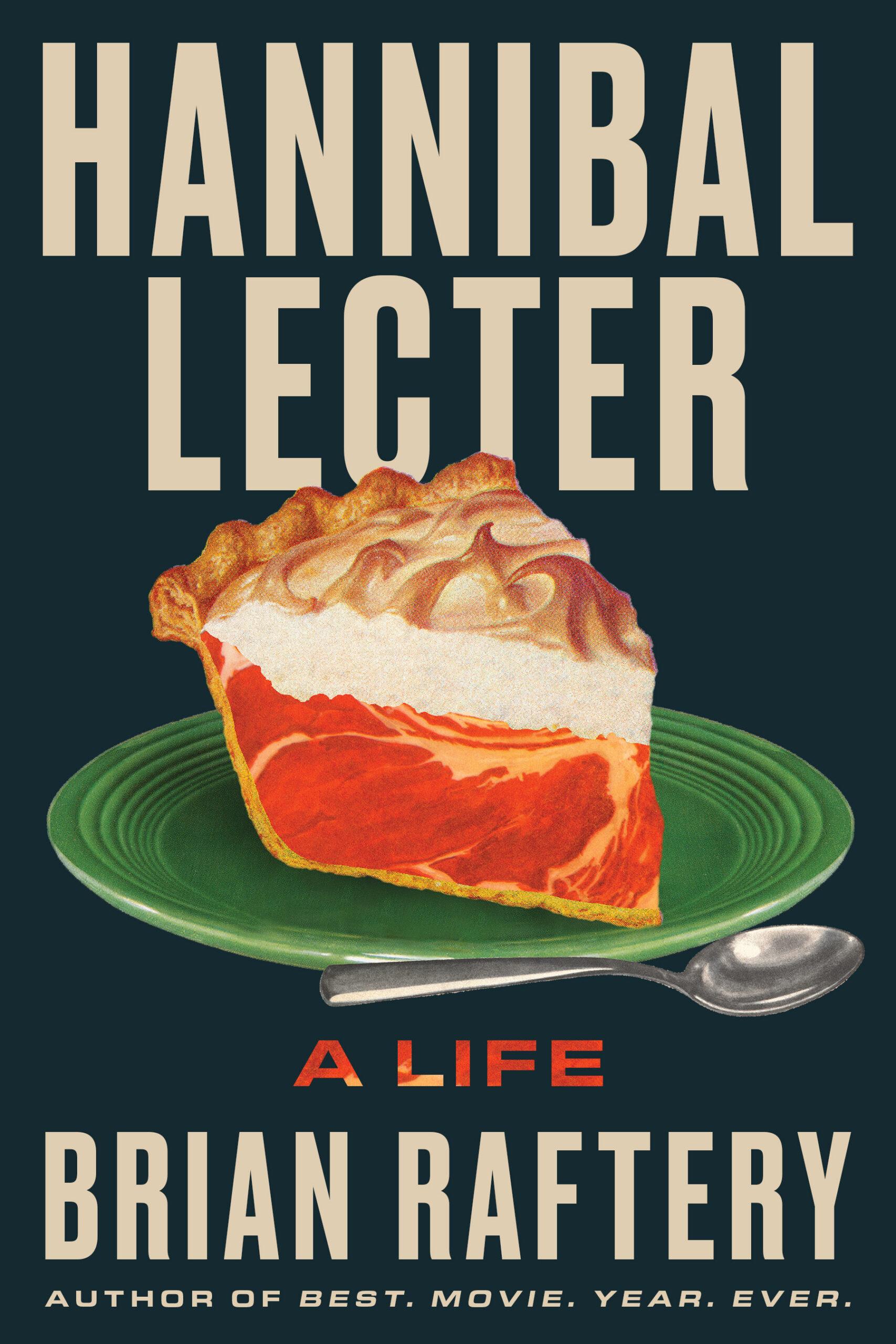

Hannibal Lecter jumped from Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon novel into cinema and television and in the process became one of the most enduring characters in American pop culture. In his new book, Hannibal Lecter: A Life, out Tuesday, Brian Raftery chronicles the many depictions of Dr. Lecter, from his literary origins to Anthony Hopkins’s Oscar-winning portrayal to his comeback in the TV series Hannibal. In this exclusive excerpt, Raftery recounts Michael Mann’s effort to bring Red Dragon to the screen in what would become his cult film Manhunter.

Even before shooting on Red Dragon got under way, it was clear that it was going to be a tight, tough production. The movie would be shot in several locations, including North Carolina, Florida, and Washington, D.C. The filmmaker would be working with not only a cast of relative newcomers, but also several non-English-speaking crew members producer Dino De Laurentiis had brought in from Italy. Throw in Red Dragon’s draining subject matter, and there were all the elements you need for a grinding gig. “The film was not a fun time,” actor William Petersen said.

The difficulties started early on. Director Michael Mann was just a few weeks into production when a tractor-trailer containing $300,000 worth of equipment was stolen from a Radisson Inn parking lot in Atlanta. Then there were flare-ups with the crew: According to Tom Noonan, on the actor’s first day of work—for a scene in which Francis Dolarhyde is sitting in a van outside Reba’s home—Mann became frustrated by “a little tiny imperfection” in the vehicle, Noonan recalled. “You’d never have seen this in a million years. He complained to the producers. He was really upset.” As a result, Noonan said, members of the film’s art department were immediately dismissed. “I learned over time that you really don’t talk back to him or give him shit, ever,” said Noonan. “He’s like Napoleon.” To Petersen, the filmmaker brought to mind a different fearless leader: “I often compare him to Bill Belichick. There is no part of the thing that he is not completely involved in, from the buttons on my jacket to the lenses he uses for his camera.” That included the film’s budget. Mann, who’d spent the last year dealing with the granular aspects of making Miami Vice, kept a close eye on the film’s financial reports—a pursuit that led to tension with De Laurentiis. “I got into some huge battles with him,” recalls Mann, who at one point confronted De Laurentiis about overtime charges at his North Carolina facility. “I would question him, and the response would be ‘Michael, why do you have to be that way?’”

The two also argued over the film’s title, as De Laurentiis insisted that Red Dragon be rechristened. Numerous reasons for the switch have been given over the years: According to one account, he felt burned by the recent commercial failure of his crime drama Year of the Dragon and believed that the D-word was cursed. The producer’s wife and creative partner, Martha De Laurentiis, would later suggest that there had been concerns that moviegoers would think that Red Dragon was about communism. And according to Mann, there were concerns that some would even mistake the film for “a chop-socky movie from Hong Kong.”

A prolonged debate followed between the filmmaker and the producer, with De Laurentiis ultimately winning. To find a new name, Mann offered crew members cash prizes of up to $200 for the best suggestion. He’d wind up receiving more than a thousand submissions. “One of my favorites,” he said, “was Don’t Go For a Ride with Francis Dolarhyde.” (The Manhunter title was likely derived from the Red Dragon novel, which features a fleeting mention of “federal manhunters.”)

The back-and-forths with De Laurentiis had become a source of frustration for Mann. But he didn’t have much time to deal with them. The Manhunter script was more than 140 pages long, which was a demanding tally for any film and an unusually high one for a thriller. In order to get what he needed, he and his crew would have to work punishingly long hours in less than two months. In Thomas Harris’s book, Will Graham’s wife, Molly, observes that “time is luck.” Mann would use that line in his script and live by it on his set. “If he could shoot twenty-four hours around the clock,” Joan Allen said of the director, “he’d say, ‘Let’s go for it.’”

Occasionally, Mann got what he needed using guerrilla tactics. For a Manhunter scene in which Graham examines evidence while on an evening plane ride, Mann and his team bought tickets for a United Airlines flight from Chicago to Orlando, timing the four-hour trip so that they’d be airborne during sunset. As the sky began to darken, he and his team got out of their seats, grabbed their equipment from their carry-on luggage, and began shooting. “We just reconstituted ourselves into a film company,” he said. “A couple of the stewardesses got upset.”

Most of the time, though, Mann didn’t have to sneak around to get what he needed. During his preproduction meetings with the FBI, he’d arranged for access to the Bureau’s J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, D.C. He was later given permission to shoot a few key scenes of Graham, Jack Crawford, and the film’s on-screen agents examining evidence in actual FBI forensic labs. “They never let anybody in,” Mann said at the time. “[But] they’re very concerned about this kind of crime. It’s on a big upswing.” Manhunter would serve as a showcase for some of the FBI’s latest tools: pinpoint-precise lasers for detecting fingerprints; bulky microscopes for analyzing hair. The criminal sciences had never been depicted as thoroughly or as beautifully. In one striking moment, an investigator examines a note written by Dolarhyde while working in a darkroom immersed in bloodred light.

It was one of many enthralling scenes Mann would create with Manhunter cinematographer Dante Spinotti. Born in Italy, Spinotti had been working largely on TV films in his home country when he met De Laurentiis. “My aim was to do movies in the USA,” he says. “A race car driver dreams of Formula One. A filmmaker dreams of Hollywood.”

De Laurentiis invited him to North Carolina to meet with Mann, who looked at some of his work and showed him Thief. In their earliest conversations about Manhunter, Mann told Spinotti about the film’s use of color. “He told me green represented danger and tension,” Spinotti remembers, “and we spoke about blue representing a sort of intensity.” Mann handed him an image from the Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte’s Empire of Light series. It featured a placid blue sky hovering over a darkened house with green-hued doors. The Magritte painting was alluring yet ominous, and Mann wasn’t the first filmmaker to turn to it for inspiration: Years earlier, the image had been the basis for a scene in William Friedkin’s horror hit The Exorcist. “Michael said, ‘This is the movie,’” Spinotti recalls. “I said, ‘OK, great.’”

As the Manhunter crew zipped from one location to the next, Mann and Spinotti began collecting a succession of evocative images: There’s Graham’s wife, Molly, covered in the midnight blue haze of their oceanside bedroom. There’s the doomed tabloid reporter Freddy Lounds, glowing a sickly orange after being set afire by Dolarhyde and strapped to a runaway wheelchair. And there’s Graham himself, standing in the middle of a rainbowlike supermarket aisle, trying to explain his deadly work to his young son.

Yet the most striking color in Manhunter is the Colgate-white look of Lecter’s cell. When Brian Cox first appears on-screen, he’s wearing an ivory-hued jumpsuit and lounging in a windowless, monochromatic room: white walls, white bars, and white furniture. The only pops of color come courtesy of Cox’s black, slicked-back widow’s peak, as well as a few academic journals and markers Lecter keeps on his shelf. “Lecter’s personality was so strong that I wanted to neutralize everything about his environment,” Mann notes. “It would be like a blank sheet of paper, so that whatever was in there—and whatever he was wearing—stood out.”

Two locations would be used to create Lecter’s home at the Chesapeake State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. For the building’s hallways and exteriors, Mann headed to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, an imposingly all-white modernist mecca. Lecter’s cell, meanwhile, was located on a soundstage at De Laurentiis’s North Carolina studios. That was where Cox and Petersen shot their characters’ first scene together. As Graham tries to recruit Hannibal to help in the hunt for the Tooth Fairy, the two men stare at each other through the bars with a mix of animosity and curiosity:

GRAHAM: Thought you might be curious to see if you’re smarter than the person I’m looking for.

LECTER: Then, by implication, you think you’re smarter than me, since you caught me.

GRAHAM: I know that I’m not smarter than you.

LECTER: Then how did you catch me, Will?

GRAHAM: You had disadvantages.

LECTER: What disadvantages?

GRAHAM: You’re insane.

Though the meeting between Lecter and Graham lasts on-screen for barely five minutes, Mann spent days filming the sequence, giving Cox time to try out the character in a variety of ways. “I played it broader, I played it louder, I played it more forceful, I played it more violent,” he said. “My bias was always to be a little bit more hidden, a little bit more unrevealed.” That was the version of Hannibal the Cannibal that wound up in Manhunter. Lecter comes off as impudent, blunt, and seemingly a bit bored—but it all feels like a ruse. The moral and emotional vacuum Cox had observed in the Scottish killer Peter Manuel would also be found within the Lecter of Manhunter.

The character’s final moment in the film consists of a brief but crucial phone call with Graham. The profiler has become stuck in his search for the Tooth Fairy, and he’s still trying, in Lecter’s words, “to get the old scent back again”—to understand a killer’s whys and hows. Lecter doesn’t think that Graham needs to search too hard for the smell, reminding the ex-profiler that Graham had shot and killed the murderous Garrett Jacob Hobbs—and that it had felt good.

LECTER: And why shouldn’t it feel good? It must feel good to God. He does it all the time. God’s terrific! He dropped a church roof on 34 of his worshippers last Wednesday night in Texas, just as they were groveling through a hymn to his majesty. Don’t you think that felt good?

GRAHAM: Why does it feel good, Dr. Lecter?

LECTER: It feels good, Will, because God has power. And if one does what God does enough times, one will become as God is. God’s a champ. He always stays ahead. He got 140 Filipinos in one plane crash last month.

Cox played the phone call scene splayed out on Lecter’s bed with a hand casually draped over his head, and his sock-covered feet propped up against the cinder-block wall. It’s an oddly comic image—one that was inspired, Mann said, by the 1959 Rock Hudson–Doris Day romantic comedy Pillow Talk. And the moment could have been even broader: At one point during filming, Cox had Lecter serenade Graham with Stevie Wonder’s recent Oscar-winning hit “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” though that moment didn’t make the final cut.

Cox’s time on the Manhunter set in North Carolina was brief and relatively painless—something that couldn’t be said for the actor playing Francis Dolarhyde, Lecter’s pen pal and fan. By the time Noonan showed up for work, he’d gained thirty pounds of muscle, and his blond, thinning hair had grown out to mid–mullet length. The transformation would give Dolarhyde an alienlike appearance—one that Noonan’s castmates would rarely see up close, thanks to the actor’s decision to isolate himself during filming. “I traveled on different airlines, I stayed at different hotels, and [crew members] all had to talk to me as ‘Francis,’” Noonan recalled. “It created this atmosphere on the set where people were frightened of me.”

Even Mann abided by those rules—for the most part. One day while Cox was in a makeup room, the director attempted to introduce Red Dragon’s murderous mutual admirers. “Noonan just ran away screaming, ‘I don’t want to meet him,’” remembered Cox. “Mann had to chase him down the corridor, shouting, ‘But he’s your friend!’”

It was Dolarhyde’s skeevy, isolated headquarters that would serve as the setting of Manhunter’s violent finale, one that’s sparked by a pair of potentially deadly epiphanies: In a dreamlike sequence full of bright light and loud new-wave guitars, Dolarhyde visualizes Reba, his sorta girlfriend, kissing one of their film lab coworkers; the moment exists only in his mind, but it’s enough to prompt him to fully embrace his Red Dragon rage. As for Graham, he takes inspiration from one of Lecter’s teachings—“If one does what God does enough times, one will become as God is”—to push himself deeper into the Tooth Fairy’s thinking, finally connecting the murders to Dolarhyde.

That’s all followed by a climactic shoot-out at Dolarhyde’s home, which had been saved for Manhunter’s final two days of work. The filmmaking team would be working on a set built for the production in a swamp alongside the Cape Fear River. “It was at a very spooky place,” Mann said. “Ocean fog would come in and you couldn’t see 10 feet in front of you.”

The killer’s dreary home also affected the mood of the Manhunter crew. “Everybody was way inside the content of the movie,” Mann says. “The movie had become their environment.” And some were eager to escape. Right before the production’s final days in North Carolina, members of the special effects team quit en masse, apparently frustrated by the long hours. Their departure posed a problem for Mann, who had to scramble to pull together Manhunter’s effects-heavy climax, in which Graham crashes through a kitchen window and shoots Dolarhyde dead. It was a fast and unforgiving sequence, one that would provide a sudden surge of ferocity in an otherwise slow-burning film. And Mann knew exactly what song he wanted to use as its backdrop: “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” the pulsing, gurgling Iron Butterfly number that Dennis Wayne Wallace had mistakenly believed to be his personal love song.

For much of Mann’s script, the filmmaker remained loyal to Harris’s novel: Though he had omitted several chapters’ worth of backstory, Mann had treated the author’s dialogue and characters with care, expertly distilling long back-and-forths into just a few exchanges. And he had taken pains to recreate some of Red Dragon’s smallest details. In Manhunter, Graham carries a Bulldog .44 Special revolver loaded with Glaser Safety Slugs, the same hardware name-checked in the book.

But the third act of Mann’s film would represent a notable departure from Harris’s novel. Whereas Red Dragon had concluded with Dolarhyde emerging from hiding to attack Graham, Manhunter would turn the profiler into the aggressor. He breaks into the killer’s lair with focused fury as “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” becomes increasingly louder and more torturous. The hypnotic mano a mano would end with Dolarhyde dead on the floor, his blood spreading around his corpse like dragon wings.

Without an effects team to handle the bullet-blasted gore, Mann and his team had to scramble, sometimes relying on DIY supplies picked up at a local 7-Eleven, including pork brains and condiments. “All of a sudden it was Filmmaking 101,” Petersen said. “[They were] shooting ketchup through a tube onto the wall.” Finally, just after 6:00 a.m., filming on Petersen and Noonan’s final showdown was completed. The two actors had stayed away from each other for months—“I never met Billy until he came through the window,” Noonan said—and they decided to get breakfast together. The Manhunter shoot had exhausted them both. “The whole thing was hard,” Petersen later said. Coming from the theater, Petersen was used to going onstage, playing his part, and then hitting the bar. “This was much more of a war of attrition; you had to somehow survive to the end.” And for Petersen, the end came much later than expected. Not long after filming wrapped, the actor was back in Chicago, rehearsing for a play. But he found that he was still talking like Graham. He eventually dyed his hair blond, “just so that I would look in the mirror and see a different person,” he said. The experience of making Manhunter—of being plugged into the mind of a serial killer—“had just creeped in.”

Excerpted from Hannibal Lecter: A Life by Brian Raftery. Copyright 2026 by Brian Raftery. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, LLC.