While about a third of the country moved its hips to the subtropical sounds of Sunday’s Benito Bowl, approximately 6.1 million people spent halftime of Super Bowl LX livestreaming a distinctly American racket. From a studio best described as Tron: Legacy meets Netflix stand-up special, Turning Point USA broadcast its “All-American Halftime Show,” headlined by three “real American” men and one “real American” woman. Spread across the 35-minute performance were handlebar mustaches, military fades, a white man with dreadlocks, and a country crooner without shoes. The most common vocal register was RFK Jr.–esque. By the time that Kid Rock came out—sporting a snow-white fur and divorcé-core fedora—failed at lip-synching, and changed into a T-shirt, I could regurgitate the fundraising text at the bottom of my screen as faithfully as the crowd could recite a certain “book” that, the MAGA rocker noted, was always in need of “dusting off.”

These are fractured, shameless times, but also terribly funny ones. On NBC, the most popular act in music—the 31-year-old Puerto Rican pop king Bad Bunny—took viewers on a journey through sugarcane breaks and coco frio stands, past tíos playing dominos and a few diablonas perfecting their acrylics. Guest appearances included Ricky Martin, Jessica Alba, Lady Gaga, Pedro Pascal, Ronald Acuna Jr., and Cardi B. There was also a digitized sapo concho, the Puerto Rican crested toad.

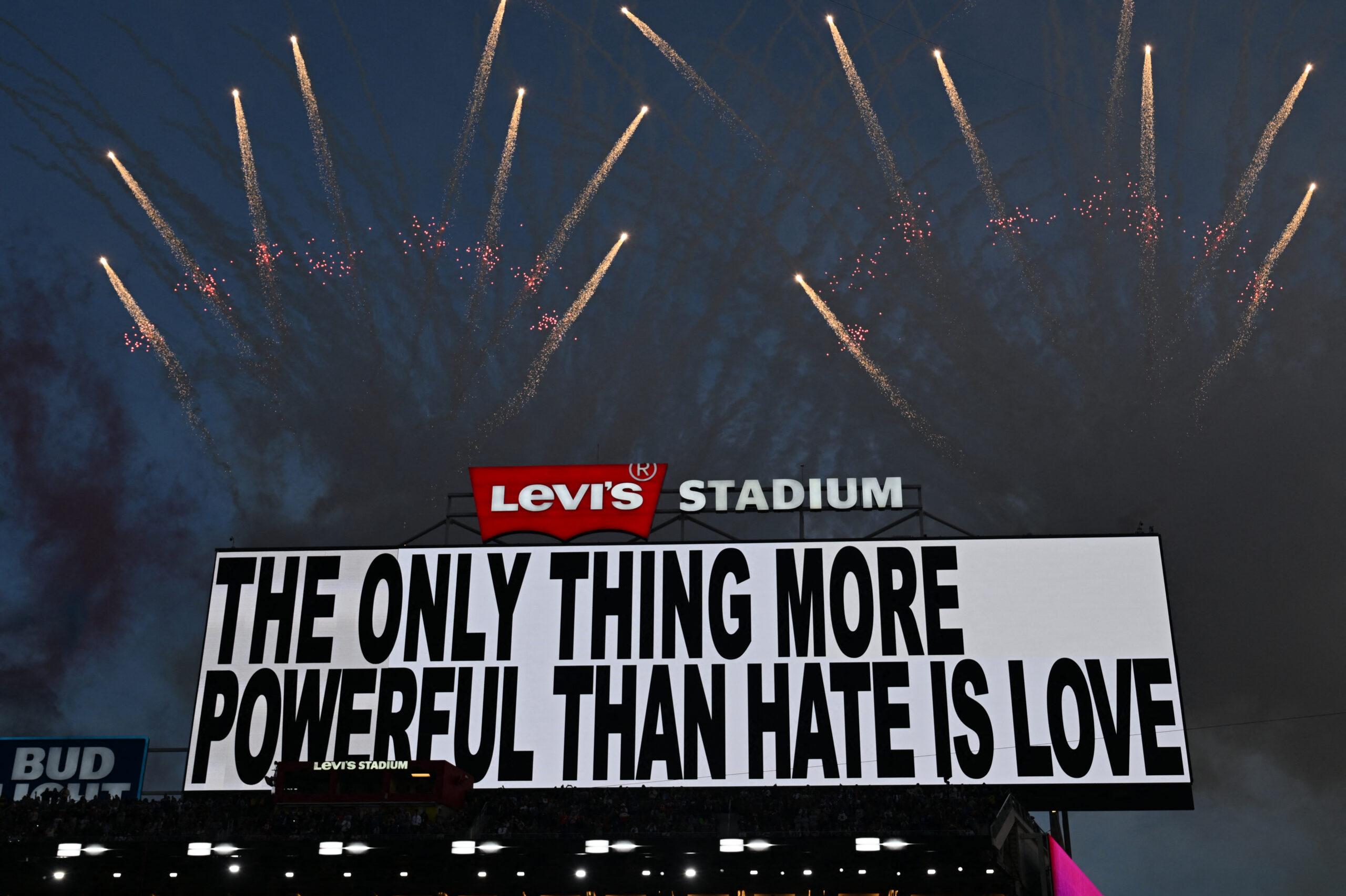

An actual wedding ensued. Bad Bunny handed a Grammy award to a young boy who may have been a stand-in for his childhood self. A few lyrics rued the fate of the world’s oldest colony: that it might be further exploited, further degraded. Most of the rest were chiefly concerned with—and wholly successful at—eliciting gyration. The parting message was “God bless America,” which followed “The only thing more powerful than hate is love” and “Together, we are America.” The country and continents did not divide. The world did not end. There was not even a squall of brimfire.

If you’d indulged in any of the fuss coming out of the Trump-industrial complex, pre- or post-performance, you’d have thought that Che Guevara was headlining the intermission. In January, the president told the New York Post that he’d be skipping the NFL’s signature event, saying of Bad Bunny’s halftime selection, “It’s a terrible choice. All it does is sow hatred.” Soon after the show—which Trump definitely didn’t watch—he took to Truth Social and ranted that it was “an affront to the Greatness of America” and a “slap in the face to the nation.” Turning Point, for its part, advertised its “alternative” broadcast—a “one-of-a-kind streaming event” featuring non-AI-generated country singers Brantley Gilbert, Lee Brice, and Gabby Barrett—as an attempt at “taking the American Culture War to the MAIN STAGE.” The announcement included a promise to supply viewers with “no ‘woke’ garbage. Just TRUTH. Just FREEDOM. Just AMERICA.”

That the most consumed artist of the decade, fresh off 15 top-10 hits and a Grammy win for Album of the Year, has become the latest focal point of the culture war is both a farce and wholly unsurprising. Despite his relatively nondescript, lower-middle-class origins (he grew up in the Almirante Sur barrio of Vega Baja; his father was a truck driver, his mother an English teacher), Bad Bunny has specialized in challenging conventions, audiences, hierarchies across his public life. He’s allergic to tailoring his art to anywhere other than his homeland. “I never made a song thinking, ‘Man this is for the world. This is to capture the gringo audience.’ Never,” he told GQ in 2022. “I make songs as if only Puerto Ricans were going to listen to them.” He was born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, and his brew of influences includes a touch of bachata, dembow, American and Latin trap, reggaeton, salsa, and mambo. The tone of Bad Bunny’s music vacillates between observational, romantic, and braggadocious, but it is almost never preacherly.

This is not to say that it is not expressly political: He’s repeatedly voiced opposition to U.S. statehood for Puerto Rico, trashed the territorial bureaucracy that has allowed rounds of energy blackouts on the island, spoken out in support of the Puerto Rican transgender community, and toyed with sexual and gender norms on- and offstage. During the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, Benito called out Trump directly, writing, “F–K DONALD TRUMP! PRESIDENTE DEL RACISMO” in a statement to Time. He voiced his objection to Trump’s mishandling of recovery efforts after Hurricane Maria ravaged the island and endorsed Kamala Harris for president in 2024. Since Trump returned to office, Bunny has called out ICE both in Puerto Rico and on the U.S. mainland—devoting one of his Grammy acceptance speeches to uplifting migrant communities. These latter acts appear to be the catnip that has the president’s zealots and underlings most charged up.

Trump’s obsession with the NFL and its cultural ubiquity predates Benito’s performance entirely. The president spent much of his middle age contemplating how to force his way into the league: first with a doomed attempt to purchase what was then the Baltimore Colts from the Irsay family, then with a history-altering choice not to buy the Dallas Cowboys for $50 million in 1983. Within the next year, he bought the USFL’s New Jersey Giants and pushed the fledgling league to sue the NFL for being a monopoly, a pursuit that would lead to bankruptcy. As recently as 2014, Trump tried (and again failed) to scrounge up enough cash to scoop up the Buffalo Bills.

Before he was outbid by current Bills owner Terry Pegula, Trump reportedly told a source—who later told Stephen A. Smith—“I’m gonna get them all back. I’m gonna run for president.” Nine months later, he was spotted cascading down a garish escalator; 17 months after that, he had a time-share in the Lincoln Bedroom.

One would think that clothing of such immense power would satisfy a former reality TV host and wrestling heel. But, of course, the lesson of the past decade is that nothing satisfies his desire for total domination. Nine months after assuming office the first time, Trump spent an evening frothing at the mouth in front of supporters in Huntsville, Alabama. A year earlier, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick had initiated a wave of protests against systemic racism in the U.S. by kneeling during pregame renditions of the national anthem. By 2017, even as the passer remained unsigned, the demonstrations lingered.

“You know what’s hurting the game?” Trump said to the crowd. “When people like yourselves turn on television, and you see those people taking the knee when they are playing our great national anthem. Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out. He’s fired. He’s fired!’”

He’d go on to urge fans to boycott the games. Players responded with multiple shows of unity. The league was caught woefully flat-footed. In 2019, the NFL came to an agreement with Jay-Z to have his label, Roc Nation, partner on production of the Super Bowl halftime shows for the next five years; Hov, ever the entrepreneur, contended that he could make the outing “all-inclusive.” This agreement, which was extended in 2024, is inseparable from the league’s decision to approach Bad Bunny to headline the intermission of Super Bowl LX—itself the latest in a series of political conflicts over who serves as entertainment for the biggest night in America.

The artists change, but the disputes are annually resurrected. Last year, Kendrick Lamar and his abiding race consciousness were the focus. In 2020, Jennifer Lopez and Shakira’s pulsating performance prompted a different kind of mania. Four years earlier, Beyoncé drew the ire of the right by debuting her trunk-rattling hit “Formation” with an accompaniment of beret-wearing backup dancers. The Super Bowl halftime show has always been a setting for controversy—from “Nipplegate” to Prince’s proclivity for phallic shadows—because it’s always been inescapable, a stage that ensures a staggering economy of eyeballs.

Despite the impulses of certain revisionists yearning for an idyllic past, halftime performance history is littered with the biggest pop acts of their times, from Michael Jackson to Diana Ross to Paul McCartney to Bruno Mars. It doesn’t take a critical lens to read the NFL’s selection of Bad Bunny this year as fitting firmly within this commercial tradition. That’s especially the case given the league’s aims to grow even bigger and more powerful, potentially through international expansion.

The institution hasn’t changed—the times have. The terms of a certain kind of politics are no longer about governing or legislating, or about economic or even social domination. MAGA wants cultural supremacy. It wants to target, pummel, and deport your neighbors or loved ones, and most of all, it wants you to sit and worship what it worships. It wants its preferences not only to be perceived as more American and more righteous, but also to be accepted as more popular. Power isn’t enough. This movement fiends for validation.

One would like to think that there exists a level of embarrassment that would promptly ensue once those assumptions are proved woefully inaccurate. That in an age when—for a crucial few—fact and decency and common interests have frayed beyond recognition, shame might still exist. If Sunday’s dichotomy is any indication, it appears that shame has fallen fully out of favor. In an All-American tradition, has-been rockers with faux furs and victim complexes as wide as Caribbean islands hid out from reality in a strangely lit corner, for fear of the joy that rung about.