In March of 2023, at the end of a thrilling World Baseball Classic, I demanded more WBCs. Almost three years later, the global game of baseball is about to oblige. On Tuesday, rosters for the 20-team, 12-day tournament—which will begin on March 5 and be played in Tokyo, San Juan, Miami, and Houston—were finalized. On Thursday, those rosters were released, which led to lots of breakdowns of the talent on tap from both MLB and international leagues. As always, stars are strewn across a multitude of teams, particularly past champions Japan, the United States, and the Dominican Republic, as well as other traditionally strong squads such as Venezuela, Puerto Rico, and Mexico. If there’s one factor that sets this year’s roster release apart and that could decide the victor, though, it’s that this time, the USA has all arms on deck—and a long-sought superteam to send to the WBC.

Everyone remembers how the last WBC ended: Shohei Ohtani fanned his then–Angels teammate Mike Trout with an exquisite full-count sweeper to seal a 3-2 victory for Samurai Japan. Fewer recall who started that championship contest for Team USA: Diamondbacks righty Merrill Kelly, who recorded four outs and allowed two runs.

In 2023, Kelly was a pretty good pitcher: He was coming off a 3.2 FanGraphs WAR season and about to begin another 3.2 WAR season. In 2026, he’s still pretty good; this year, he’s coming off a 3.1 WAR season. But he’s not on Team USA’s 2026 roster, and if he were, he’d have a hard time earning any starting assignment, let alone the nod in a do-or-die game. In the sixth WBC, pretty good doesn’t cut it for Team USA, which has finally fixed a problem that has plagued it since the inaugural tournament 20 years ago: a failure to recruit top pitchers.

Despite the capacity to assemble more superstars than any other entrant—thanks in large part to a population that’s about as big as Japan’s, Mexico’s, South Korea’s, Venezuela’s, and the Dominican Republic’s combined—the country of baseball’s birth has claimed only one of the first five WBC titles (in 2017). The primary impediment to U.S. WBC dominance has been an absence of aces, which was glaring in 2023, when one former WBC player told reporter Jon Heyman that Team USA sported its “weakest pitching staff ever.”

“Team USA’s pitching staff is essentially a ‘B’ team; none of the 14 American pitchers who received Cy Young votes last season are on the roster,” wrote The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal that spring. According to Rosenthal, the thinness of the U.S. staff—coupled with MLB team–imposed restrictions on pitcher usage that sometimes left Team USA manager Mark DeRosa scrambling for available arms—raised “a frequent and existential question regarding the WBC: If the U.S. cannot give full effort, why bother? … For the WBC to truly succeed, a greater U.S. push is required, not just by teams, but players, too. If Julio Urías could pitch for Mexico and Shohei Ohtani for Japan as they enter free-agent years, why don’t more U.S aces participate?”

In the L.A. Times, Jorge Castillo echoed those concerns and pointed to many other arms who had answered the call for clubs other than Team USA: not only Ohtani and Urías, but also Yu Darvish, Sandy Alcantara, Cristian Javier, Pablo López, and José Berríos. “Attracting the best available starting pitching is an acute obstacle only for Team USA,” Castillo wrote. “Take a look around the tournament. The best pitchers from the other contenders are participating.” Elsewhere in that article, DeRosa added, “If this is going to go where it needs to go, then all teams, all countries would want their so-called best players. And it shouldn’t be as difficult as it was to put a roster together.”

It’s debatable that the WBC needs better U.S.-born pitchers to flourish; without them, the 2023 tournament was a huge hit in terms of attendance, TV ratings, and entertainment value. But it does detract from the fun and intensity when some stars pass on playing. The five most valuable MLB pitchers of the WBC era—Justin Verlander, Clayton Kershaw, Max Scherzer, Zack Greinke, and Chris Sale—are all U.S. born, and none of them have thrown a pitch in the tournament. Verlander, who debuted in MLB the year before the first WBC, has consistently declined invitations. Kershaw tried to play in 2023, but his hope was thwarted by insurance issues, which Team USA (unlike some other clubs) has largely avoided this year. (Kershaw has joined the 2026 roster for a preretirement swan song.) In 2023, Scherzer said, “I’m not ready to step into a quasi-playoff game right now. If I do that, I’m rolling the dice with my arm.” He suggested that the tournament be moved to midsummer.

Days after Scherzer’s comments, Heyman said, “It’s just kind of the mindset of the American players and the fact that they want to be cautious and be ready for the season and not take any chances.” Some prominent U.S.-born pitchers have almost been belligerent about their anti-WBC bias. When reporters questioned Noah Syndergaard during spring training in 2017 about whether he regretted not suiting up for Team USA, he said, “Nope, not one bit.” When asked to explain why, he responded, “Because I’m a Met. Ain’t nobody made it to the Hall of Fame or the World Series playing in the WBC.”

Players from some other countries have more extensive track records of competing for national teams in regional tournaments such as the Caribbean Series and the Asian Baseball Championship. Players from the place that’s presumed to be the best at baseball may feel less incentive to put that reputation on the line than players from other nations do to make the case for their countries. And the specter of injuries in WBC games still looms (not that injuries don’t also strike in spring training). But just as NBA teams have started to treat the NBA Cup as an achievement worth sweating for rather than a frivolous side quest, U.S.-born pitchers have belatedly gotten on board with the WBC.

Last December, DeRosa repeated the refrain from 2023: “You see it from every other country. Their best arms show up. For whatever reason, in the United States, our best arms don’t show up.” However, he also sounded an optimistic note: “That being said, we’re trying to change that narrative.”

Whatever DeRosa did differently as a lobbyist for the 2026 team may have helped, but as the skipper said, the WBC itself made the most persuasive case:

I think guys who watched in ’23 and saw the game against Japan, saw the iconic moment between Trout and Ohtani, saw Trea Turner's [grand slam] against Venezuela … it's like, man, these are moments in time. And you got a chance to do that. My pitch has been completely different this time. It's like, “You're gonna miss out on three weeks of the greatest time of your life as a ballplayer, unless you win a World Series.” That's what this is becoming. I mean, you see the way Latin America and Japan and everybody is [treating the event that way], and I just feel like there's been a groundswell with the United States players that, “All right, it's time for us to go.”

DeRosa was right: To invoke an old tagline attached to a previous MLB-organized marquee event, U.S. pitchers are approaching the 2026 WBC as if this time, it counts. Paul Skenes committed to the team last May, as the reigning NL Rookie of the Year was putting together what would become a Cy Young–winning campaign. Last year’s other Cy Young winner, Tarik Skubal, followed suit shortly after the Winter Meetings, as did Logan Webb, who had initially pledged his nasty sinker and changeup to the 2023 club before flip-flopping. Joe Ryan joined these once-elusive aces, and Mason Miller signed up to hold down late-inning leads.

We can quantify the resulting glow-up of the Team USA staff with help from player projections provided by ZiPS creator (and FanGraphs senior writer) Dan Szymborski, who has published his system’s prognostications annually dating back to 2005. ZiPS projects Skenes, Skubal, and Webb to be three of the four best MLB pitchers in 2026, along with Garrett Crochet, who seemed tempted to pitch for Team USA as of last summer but ultimately opted not to after incurring a career-high workload in 2025.

The table below lists the top four starters on each Team USA squad’s staff, going by the average of fWAR from the preceding season and ZiPS-projected WAR for the ensuing season. Not only is this year’s quartet of Skubal, Skenes, Webb, and Ryan easily the strongest as a unit, but each individual member is also the best ever in his respective starting slot. In addition to outclassing the competition toward the top of the rotation, this year’s staff runs deep: Its fifth- and sixth-best starters (Michael Wacha and Matthew Boyd, at 2.9 WAR apiece) have higher figures than the fourth-best starter on any previous roster or the third-best starter on the 2023 team. Heck, this year’s seventh- and eighth-best starters (Clay Holmes and Kershaw, at 2.0 WAR each) trump the third-ranked starter from 2013.

Top Four Starting Pitchers on Each WBC Team USA Squad (Avg. of Past and Projected WAR)

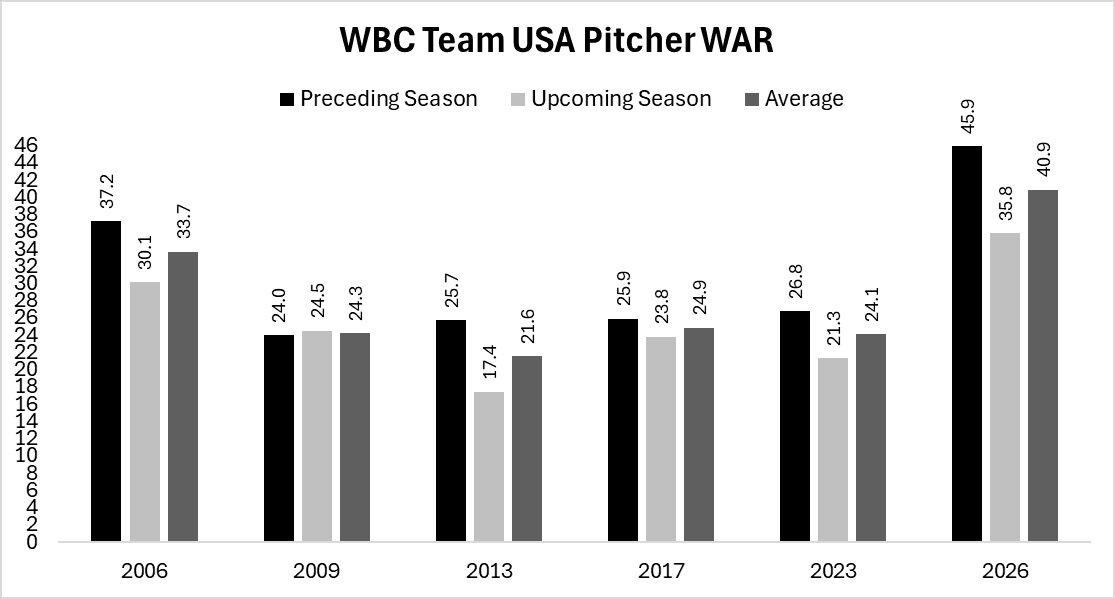

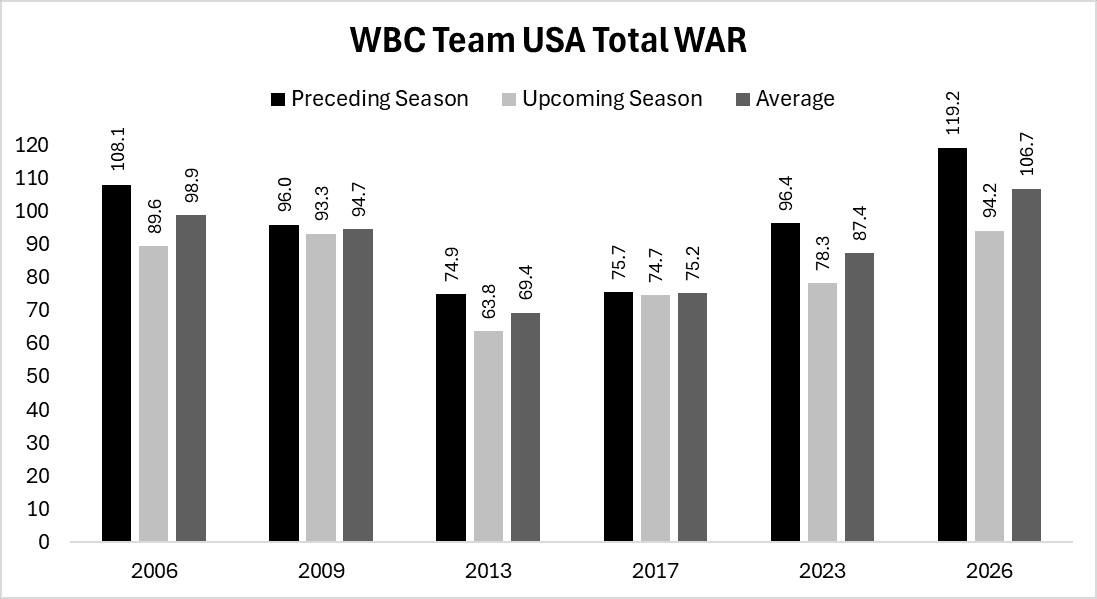

We can expand the scope of our projection scouring to consider the strength of the staff (and the roster) as a whole. The chart below shows the strength of each year’s full complement of pitchers on Team USA as measured by their cumulative fWAR in the preceding season (the black bar), their cumulative projected WAR for the upcoming season (the light gray bar), and the average of those two totals (the medium gray bar). One caveat: The 2013 and 2017 rosters featured 28 and 29 players, respectively, compared with 30 in all other years. But that doesn’t affect the obvious takeaway: This year’s staff is stacked.

This year’s pitchers clear the previous highs by more than 8 preceding-season WAR, more than 5 projected WAR, and more than 7 WAR in the blended average—and all of those earlier records were set two decades ago, in the first WBC. Compared with any of the post-2006 Team USA rosters, this year’s unprecedented crop of pitchers is, at minimum, 71 percent better in prior-year WAR, 46 percent better in projected WAR, and 64 percent better in the mixture of the two. In 2023, six WBC starts went to Kelly and a superannuated Lance Lynn and Adam Wainwright. This is a night-and-day difference.

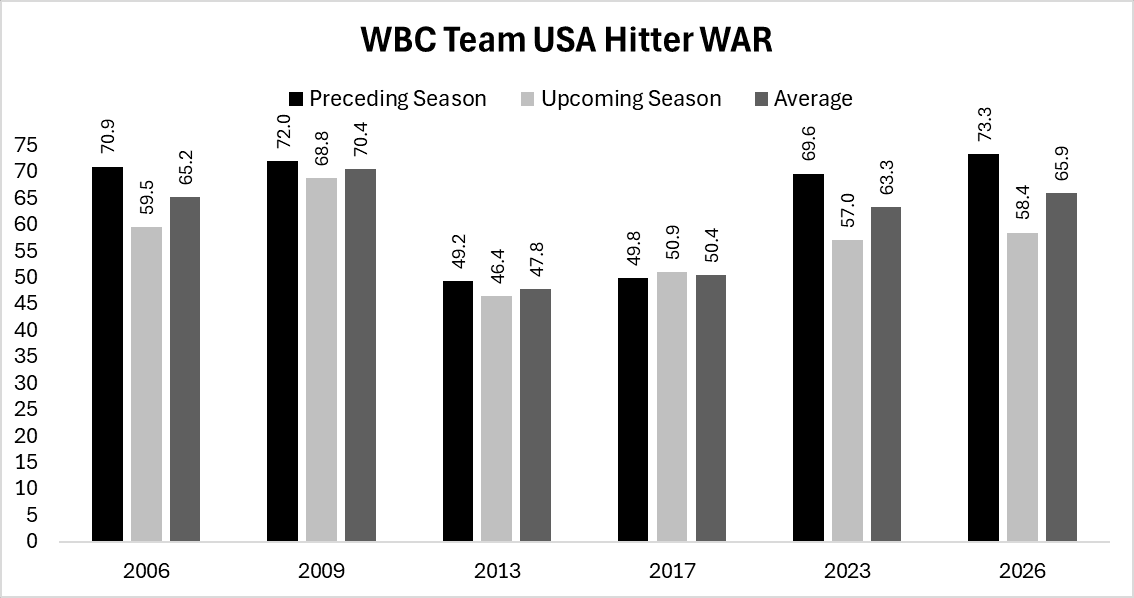

These dramatic upgrades on the pitching front haven’t come at any cost to the quality of the position players. In Aaron Judge, Cal Raleigh, Bobby Witt Jr., and Gunnar Henderson, Team USA boasts three of MLB’s four best ZiPS-projected batters and four of the top seven. Imagine Henderson being bumped off shortstop, Brice Turang (a narrow runner-up among second base WAR leaders last year) possibly being benched, Will Smith being a backup catcher, and either Byron Buxton or Pete Crow-Armstrong serving as a fourth outfielder. Did we mention Alex Bregman and Bryce Harper at the infield corners and Kyle Schwarber at DH?

This year’s collection of position players is also the best ever by preceding-season WAR and the best in the other two categories since 2009, when DeRosa (who’ll turn 51 before this year’s WBC) was playing for Team USA. Combine the batting and pitching, and by any measure, this edition of Team USA is unquestionably better than any previous version (and, for that matter, almost certainly any WBC squad) has ever been. This is the first time that the old adage about how you can never have enough pitching might not apply to Team USA—and the first time that an American club in the WBC can truly aspire to a “Dream Team” label.

Naturally, none of this means that the souped-up pitching and superpowered all-around roster—ripe as it seems for revenge for the finals loss last time—will perform up to expectations or that Team USA will run roughshod over the field. Team USA will play, at most, seven non-exhibition WBC games, and the MLB postseason has schooled us on how unpredictable that few contests can be. Maybe that’s for the best: Lopsided victories can be boring. Still, even though the other leading contenders (Japan and the DR foremost among them) are no pushovers, Team USA is a heavy favorite, in contrast to 2023. In light of the Trump administration’s bullying behavior on the international stage, the U.S. doesn’t make for the most sympathetic sports powerhouse. Maybe it should embrace being the heel; at long last, it has the pitching to play the part.

In the coming days, pitchers and catchers will report to camps across Arizona and Florida. For the first time since the WBC started providing periodic respites from the monotony of spring training, though, the Cactus and Grapefruit Leagues will be brief layovers for many of MLB’s best U.S.-born pitchers. Come March, they’ll be on the move to test their stuff against the best of the rest of the world—and, in the process, demonstrate the untapped potential of a fully operational, two-way Team USA.