I.

Like the rest of St. John the Baptist Parish, Robert Taylor had no idea that the curse haunting his kinfolk dwelled in the air. Nestled along the banks of the Mississippi River—in the center of an 85-mile industrial zone known today as “Cancer Alley”—St. John was, for centuries, a vital organ in Louisiana’s sugar empire, tilled by legions of enslaved and tenant laborers. Taylor’s parents moved to the area in the 1930s and worked at one of the large nearby cane refineries. The 84-year-old has lived on the east bank of the parish since he was a child, over which time different mutations of cancer have plagued his relatives with alarming regularity.

“My mother died, then my brother, my sister,” Taylor told me in August, in the home he built in his youth and rebuilt after Hurricane Harvey. His wife, Zenobia, “came down with the cancer,” too. She passed away in 2024.

Cancers striking four times in a single family is an incomparable calamity, but in St. John it is not exactly an anomaly. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the risk of getting the disease in the parish is 47 times higher than in the rest of the United States. In 2024, the most recent year with available EPA data, 11 plants combined to release more than 762,000 pounds of toxic chemicals into the air in St. John. Residents here face the highest likelihood of developing cancer through air pollution in the entire country.

The term “sacrifice zone” is often referenced in academia and among the parish’s fence-line communities when explaining how political and economic life in St. John orbits around the whims and needs of global industry. Sitting on a black leather couch in Taylor’s living room, I asked him what the phrase conjured in his mind. He gazed out from behind a pair of wire bifocals. “It’s a zone set aside,” he said in a sanded-down country twang, “where they can come in and make money. It doesn’t matter that it’s going to destroy the local people.”

Although a number of facilities operate on the old plantation grounds that dot St. John, Taylor’s life has been entwined with one in particular: a synthetic rubber plant, 2 miles from his home, on a former sugar estate in the town of Reserve. For six decades the factory was owned and operated by an $18 billion multinational chemical producer named DuPont de Nemours; since 2015, it’s been run by the Japanese conglomerate Denka. Taylor told me that he remembers the site opening without much fanfare back in 1964. “The whites started moving out,” he said. “Selling their homes to the local Blacks. Because they lived on the front in the better houses. … They didn’t know those people were getting out because they knew what was coming.”

The facility would go on to process neoprene, a popular rubber substitute that produces a colorless by-product called chloroprene. Since 1999, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has considered chloroprene a human carcinogen: It substantially increases the risk of cancer in the liver, lungs, and digestive and lymphatic systems, among other side effects. Through air vents, the Reserve plant disposed of more than 115 tons of the chemical yearly by the mid-2010s.

In 2016, alarmed by a long-awaited EPA air toxicity report, Taylor and a group of residents formed an environmental nonprofit called Concerned Citizens of St. John. They would eventually entreat the EPA to push for lower facility emissions. The Biden administration opened a civil rights investigation at their request and later brought a civil lawsuit against Denka. National policy for hazardous air pollutants at the time defined the highest acceptable threshold for lifetime cancer risk as a 1-in-10,000 chance. The EPA’s subsequent inquiry found that infants born “in the communities surrounding” the plant exceeded that threshold by the time they were 2.

The people who got the ability to impose their will on us here in this community have decided that our lives are not worth anything. They can come in here, do what they can do, just like they’re doing. They can suffer the horrors of you dumping these chemicals and pollutants into their bodies.Robert Taylor, St. John the Baptist Parish resident

But upon returning to power in 2025, Donald Trump instructed the EPA to drop its case outright. The White House, citing the president’s “mandate to end radical DEI programs,” described the original litigation as “a clear example of racial preferencing.” The regulatory maneuver was one in a series of federal actions concerning race, ideology, and industry with direct impacts on the parish.

In February, the Trump administration’s then-appointee to run the National Park Service pulled two newly eligible districts in St. John from consideration for the National Register of Historic Places. According to multiple reports, the NPS also halted proceedings for an 11-mile portion of the majority-Black parish’s west bank to be designated as a National Historic Landmark zone. In April, another federal agency cut funding for the Whitney Plantation museum—the first institution in the U.S. devoted exclusively to studying enslaved life—in west St. John. Then, in July, Trump formally exempted both Denka and DuPont from a set of EPA manufacturing directives intended to reduce airborne cancer risks. (Denka had announced in May that it was suspending production indefinitely in the parish, but cautioned that “no decision regarding a permanent closure” or potential sale of the facility had been made. The company did not respond to The Ringer’s request for comment.)

A little over a week ago, The New York Times reported that the EPA will cease considerations of mortality and health benefits when weighing the merits of clean air regulations in affected communities like St. John. An EPA representative provided a statement to The Ringer that said, “As usual, the premises of The New York Times’ headline and article were inaccurate. … EPA absolutely remains committed to our core mission of protecting human health and the environment.” The spokesperson added: “If you had been paying attention at all, you would know that the Biden administration also didn’t monetize many air pollutants in their rules. No one questioned if they were following the agency’s core mission of protecting human health and the environment. Not monetizing DOES NOT equal not considering or not valuing the human health impact.”

That a 40,000-person industrial hub on the midsole of Louisiana’s boot finds itself so thoroughly enveloped in the vortex of Trump’s wider culture war is, from one angle, profoundly discombobulating. To those most familiar with St. John’s various semblances, though, the area’s tendency to mirror and magnify the interests that guide it is painfully on-brand. At present, the executive branch appears willing to use St. John as collateral in the enactment of an agenda devoted as much to the politics of cultural obliteration as to domination. Yet one cannot reconcile what has unfolded in recent months across this long-abused stretch of Louisiana riverbank without first contending with the notion that these events are part of a much larger national reckoning.

If there is an ineluctable truth illuminating the first year of the reinstalled Trump regime, it is that the ways in which America commits itself to memory—how it preserves and prioritizes its distinct and overlapping cultural legacies—are at once inherently vulnerable and innately tied to the state. So much so that the act of cutting off funding or ignoring a petition for protection amounts to a form of ideological warfare. And the terms of these forays are both intended and felt in expressly material fashions. Disputes over libraries today bleed into tussles over monuments tomorrow, which escalate into clashes about clean air the next day. Campaigns against “wokeness,” “unpatriotic education,” and “discriminatory DEI practitioners” merge with rants about “divisive race-based ideology” in the Smithsonian and content that “disparages Americans” at the national parks. In an America made great again, the roots of these conflicts don’t just overlap. They’re fused together.

What has unfolded over the past year in St. John the Baptist Parish isn’t simply evidence of an administration opposing citizens like Taylor. It is confirmation of that administration’s hostility to their heritage and democratic will—so long as each contradicts the president’s preferred worldview. This, for the parish, is rather familiar territory. For the better part of three centuries, its inhabitants have outlasted some version of existential duress. That dogged persistence is practically hemmed into the terrain of the place: The levees, cane swaths, and petrochemical sprawls band together, in sequence, refusing to end. Left unimpeded, the Mississippi meanders in the Land of Louis and reclaims old veins.

“The people who got the ability to impose their will on us here in this community have decided that our lives are not worth anything. They can come in here, do what they can do, just like they’re doing,” Taylor told me in his family’s den. “They can suffer the horrors of you dumping these chemicals and pollutants into their bodies.”

He shook his head.

“Sacrificed,” he said. “For the benefit of the riches of these other people. People that’s not even from here.”

II.

On St. John’s west bank, the town of Wallace is divided by thin asphalt lanes, stretching back from the levee. Surrounding the hamlet—to the north, south, and west—are endless fields of sugarcane, at least 10 feet high, with tips prone to curl like verdant dog ears. If you look eastward, toward the winding concrete hummocks that control the Mississippi, you’ll see a serpentine turnpike known as the River Road. Off one flank are old plantation manors and cabins that once housed enslaved workers and sharecroppers.

Last year, two districts along the route were nearly included in the National Register of Historic Places, and another stretch was under consideration to become a National Historic Landmark. Together, these designations would have brought a number of benefits to St. John: public and private grants, tax incentives, technical preservation services, and heightened historical and environmental protections. That is, until the efforts stalled.

Joy Banner, an activist behind the preservation push who has both free and enslaved ancestors from Wallace, told me in August that she was disappointed with the recent developments, although not exactly surprised. “I still feel cheated. I still feel robbed,” she said, pacing a grassy plot dividing an enclave her family helped found a century and a half earlier. “Yes, it’s a protection. But it’s [also] the acknowledgment.”

Banner, 47, grew up a few hundred yards off the River Road. Her mom’s side of the family has lived in St. John since before the route was built. I asked her whether she knew how far we stood from where her ancestors were held in bondage. “Maybe 5 miles that way. And then 1 mile that way,” she said, pointing to the south.

Because of a controversial zoning change in the 1990s, the multi-acre swath of sugarcane that borders Banner’s community is classified as commercial in nature. In 2021, a Colorado-based grain company named Greenfield purchased much of that land and set out to build a crop elevator roughly the size of the Statue of Liberty on it. Joy and her twin sister, Jo, sued the parish through their local health and preservation nonprofit, the Descendants Project, in hopes of stopping the venture.

Soon after, a 2022 investigation by ProPublica found that the firm Greenfield had hired to identify potential preservation risks amended a report on the project after facing pressure from the company that Greenfield had contracted to handle permitting. The original draft warned that construction could have a number of deleterious effects on the surrounding community, including disturbing the unmarked burial grounds of enslaved people. (Greenfield denied any involvement at the time.) Because a proposed terminal would have connected to ships docked on the Mississippi, by federal mandate the grain company had to acquire a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The corps denied its request, citing similar concerns as the consulting firm, and recommended the two aforementioned River Road districts for the National Register. The NPS weighed the submissions, and up until last year seemed prepared to finalize the move.

Then, last February, the agency changed course. The proposed historic districts were retroactively deemed ineligible for inclusion in the National Register, and the landmark pursuit withered. Jeff Landry, the Republican governor of Louisiana, praised the decision and said that he looked forward to “considering new projects like the Greenfield grain elevator.” A spokesperson for Greenfield, which had suspended the project, told reporters that the company remained “committed to the community of Wallace and its potential for development.” When asked for comment by The Ringer, a representative for the National Parks Service wrote that the decision was made “in response to a request for reconsideration from the State of Louisiana’s Department of Environmental Quality.”

If your plantations are historic, we’re direct descendants of people that were enslaved on [them]. So we’re historic.Joy Banner, local activist

When we met in person, Banner told me that she views preservation work as part conservation and part agitation. So far, her and her sister’s nonprofit has bought eight historic properties in the parish and refurbished them for educational purposes. Before Joy made the jump to activism, she taught at Huston-Tillotson University and later served as communications director for the nearby Whitney Plantation museum. Around St. John, Banner admits, her organization is best known for “the shit we stir.”

“We’re not harmless. And we have litigation,” she said, brow slightly furrowed. “Industry is most afraid—as it should be—of risk.

“We communicate the risk.”

Not everyone in the parish agrees with the nonprofit’s aims. A substantial portion of even those most affected by pollution and displacement in the community contends that the economic gains outweigh the costs, despite extensive evidence to the contrary. (Just last year, one study of employment equity in petrochemical manufacturing throughout Cancer Alley found that “People of Color were consistently underrepresented among the highest-paying jobs and overrepresented among the lowest-paying jobs.”) In St. John, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who isn’t connected to the industry in some way, by blood or by choice. Banner’s usual response to the supposed benefits of job creation is to point to the broader impacts and lack of uplift. “There’s already this idea that [Black] people in general should get out of the way of industry,” she said. “White people are looked at as true victims. ... When they come and cry tears of, ‘I don’t want to leave Papa’s land,’ people will listen to their tears more, and they will have solidarity with our politicians and with our lawmakers. Whereas with Black people, it’s like it gets to the heart of, ‘Well, y’all are not really American citizens, anyway.’ And more so, ‘Y’all ain’t got nothing.’”

One of the buildings that the Descendants Project purchased was a former slave cabin constructed a few miles down the road from the Banners’ property. To move the structure from its original site, Joy and her sister had a truck tow it over. Now it sits next to a mammoth live oak tree, 50 yards from the levee, its exterior repainted white and tin roof refurbished.

Similar shacks in the area are often left in derelict condition, owing largely to how little attention they receive in comparison with plantation manors. As we summited the front steps of the building, Banner said that she was rankled by this pattern. “If your plantations are historic,” she said, “we’re direct descendants of people that were enslaved on [them]. So we’re historic.”

Inside, electrical wiring was exposed and construction tarps were spread out over the hardwoods. In one room, some of the old markings on the studs were still visible. The beams were originally fashioned and placed by enslaved carpenters. “Our architect,” Banner said, pointing to a cluster of lines in the wood. “He was explaining to us how labor-intensive it would’ve been doing this.”

Later, we ambled toward the back of her neighborhood on grass that cradled droplets of warm Louisiana dew. Banner’s mother and father still live a few houses over. Her sister’s home is even closer. Her aunt dwells a couple of doors down. We looked out at the long, narrow plot and the levee beyond it. Cicadas warbled from the cane fields. “This is one parcel of land—the one tract starts at the River Road and goes all the way back,” Banner said, her eyes scanning the distance. “This is literally designed for commerce.”

III.

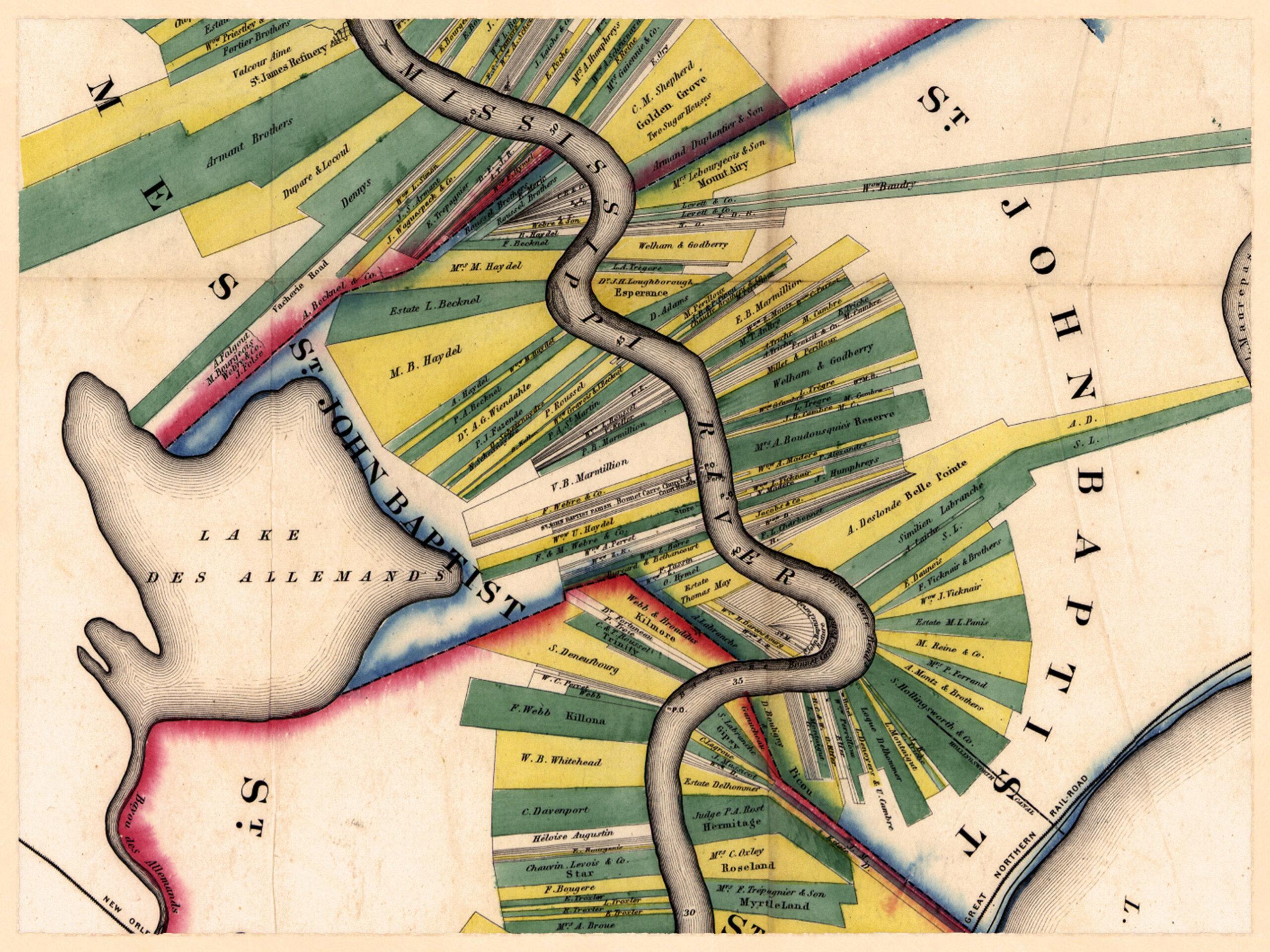

The French had thought it up this way centuries earlier. They used the term arpent, meaning “acre,” although that definition fails to convey the true economic design embroidered in the word. Thin strips of land extending from the fertile riverbanks like keys on a grand piano, arpents existed to ensure that every eligible property owner received a similar dose of the choicest terrain. In St. John, where Europeans began arriving en masse in the early 1720s, the parcels stretched out to only a few acres in width. They were not just a method for dividing estates but a blueprint for an extractive society—the solution to a problem spawned the moment the fur trader René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, first gazed out on a vast drainage basin, termed Misi-ziibi by the Ojibwe people, and claimed it and its floodplains for his benefactor, Louis XIV of France.

Known initially as the German Coast, a territory including modern-day St. Charles Parish to the south, St. John was settled by German and Swiss immigrants drawn to the region by French property offers. In 1722, these migrants formed a village just below the current town of Lucy, in west St. John. In exchange for one to five arpents, yeomen were tasked with harvesting enough produce to feed the then-fledgling outpost of New Orleans, 30 miles to the south.

Generations of Chitimacha, Houma, Bayogoula, and Chickasaw bands had already built levees along the riverbanks, but the acreage between these modest embankments and the neighboring swamps needed to be cleared for commercial agriculture to flourish. Early white settlers attempted to enslave the Native inhabitants of the region to complete this task; they found them difficult to subdue, owing—as one homesteader put it—to “the great facility they have in deserting.” Farmers soon requested captive Africans from colony officials to turn a greater profit. “Everybody, Gentlemen, is asking for Negroes,” a French commissioner wrote to the conglomerate charged with governing the territory. By 1724, 15 of the 60 white German Coast families enslaved at least 27 people. That latter number would more than triple within a decade.

From 1762 to 1800, the enslaved population in Louisiana increased by 250 percent. Thanks to this wider labor pool, St. John and the surrounding area were branded as the Cote d’Or, or Golden Coast, for its productivity. In 1768, French Canadian exiles formed a village in present-day Wallace; within a generation, farmers all over St. John introduced sugarcane, the crop that would define the next century and a half in the parish.

Innovations in cane granulation spurred a land frenzy up and down the coast and led to further influxes of enslaved laborers. Captives were smuggled illegally from Africa and the Caribbean. The topography of St. John was razed and re-tilled. Large estates—owned by French, Creole, Cajun, and American elites—subsumed smaller farms. Sugar barons fleeing the Haitian Revolution soon set up shop along the Mississippi. By 1860, chattel laborers numbered 4,594 (some 58 percent of the population) in St. John; planter elites with holdings of 420 arpents or more constituted just 11 percent of the total landowning citizenry but held approximately 55 percent of all land parish-wide. “The true spirit of commerciality reigns supreme,” a German immigrant visiting St. John noted just before the U.S. purchased the territory. “The right and moral value of a person is measured by the size of his moneybag.”

Everyone was tied to the sugar industry in some way—even a few free people of color owned captives. The Civil War arrived and nearly destroyed agriculture in St. John, but in its wake an eerily similar economic order arose. By 1875, The Daily Picayune reported that “planters” and “their overseers” had “engaged all the colored people” in St. John and the other sugar parishes “to work.” Sharecropping became the primary form of labor used in cane harvesting. In 1880, just 1.5 percent of the farms in the parish ran on tenant labor; by 1910, that number rose to 33 percent. Many of the Black residents who tilled the plantations along both riverbanks lived in the same cabins and structures that enslaved families had previously occupied.

A number of chemical companies started to purchase land on the parish’s east bank in the years before World War II. Oil and natural gas corporations followed suit in the 1940s and ’50s. The former sugar estates, with their proximity to the river and large swaths of car- and rail-accessible lands, were especially appealing. From 1935 to 1974, farmland acreage in St. John dipped by 40 percent. Louisiana’s state and local governments began to provide subsidies and tax breaks to attract new companies. Day-to-day life in the parish tilted toward the petrochemical industry, as it had toward subsistence and sugar farming a century and a half earlier.

Joy Banner’s family was swept up in the tail end of this process in the 1990s. With the support of St. John’s municipal council and president, a Taiwanese company named Formosa Plastics had set out to build one of the world’s largest rayon factories in Wallace. Banner told me that Formosa representatives eventually convinced her elderly grandparents to sell a portion of their land. Others in the community auctioned off some of their property holdings as well. In the end, the project floundered because of local pushback, but the zoning changes enshrined in this effort were what ultimately allowed Greenfield—the Colorado company that nearly built the neighboring grain elevator—to propose its own facility.

You can’t erase history. What Louisiana is trying to do, and what the federal government is trying to do on the behest of Louisiana, is [to] fool industry, as if these designations change the history. It’s all subterfuge.Banner

If National Register and Landmark statuses were implemented along the River Road, the moves would require any new development proposals to adhere to heightened preservation and emission standards. From the air-conditioned kitchenette of her nonprofit’s office, Banner explained to me that part of the reason she suspects the state petitioned the Trump administration to drop the two districts from register consideration was to make the area more enticing to developers. Even without these protections, she maintained hope that enough barriers are in place to force any interested parties to tread lightly. “You can’t erase history,” Banner said. “What Louisiana is trying to do, and what the federal government is trying to do on the behest of Louisiana, is [to] fool industry, as if these designations change the history. It’s all subterfuge. Broadcasting—telegraphing—to industry that ‘No, no, no, there’s no problems here. No, come on in. We cleared the way.’”

I asked how much she connects Wallace’s current struggle over land use to the centuries-long legacy of commercial enterprise in St. John. “It all comes down to power and the control of extraction,” Banner told me. “Sacrificing certain people in certain communities in order to justify profit and capitalism. It’s no coincidence that it was a Black community—our ancestors—who were sacrificed, all for the plantation empire. The plants are literally on the same ground.”

After resting away from the heat, Banner and I hiked across the River Road and up the levee before heading back to town. On our way, we strolled beneath another colossal live oak, a few yards ahead of the one I’d spotted earlier. Banner noted that both trees were at least 300 years old. Three adults, hand in hand, would not have been able to encircle either. The cheat code to their growth, she said, is the dirt.

Sugar has no business sprouting outside the tropics, but the alluvial deposits on the riverbanks in St. John make the proposition feasible. Truth be told, nothing we had just looked at has much business being there: the crops, the porous little dead-end lanes, the genealogical hodgepodge of a populace, the petrochemical plants themselves. But there they all were, thanks as much to the persistence and ambitions of folks who were freely or involuntarily made American as to the sheer might of the 2,340-mile coronary waterway at their nation’s center.

Standing a few yards from the house where her ancestors were enslaved, Banner said that the oaks had been there all her life. Many lives before that. “They’ve seen everything,” she marveled. “Louisiana soil—you can grow anything in it.”

IV.

“For me, it doesn’t really matter whether they believe it or not,” Ashley Rogers told me of the White House campaign to defund her line of work. “It’s got the same result.”

Rogers, the executive director of the Whitney Plantation museum, sat beside a wooden conference table in a former slave dwelling on the Wallace estate. A pair of windows behind her looked out on a portion of the 273-year-old plantation; gazing at the landscape, I wondered whether we had slipped back in time. Since the museum opened in 2014, Rogers has helped transform Whitney into a one-of-a-kind archive on enslaved life. In early April, she received a letter from the acting head of the Institute of Museum and Library Services about a series of clawbacks initiated by the Trump administration. The dispatch declared that a grant the museum had received in 2022 was now “no longer consistent with the agency’s priorities” and was outside “the interest of the United States.”

When we first spoke in May, a few weeks after the decision, Rogers told me she hadn’t been caught flat-footed: The museum had already processed and spent the full grant in the months leading up to Trump’s return to office. By the time Whitney received the revocation notice, there were no funds left to rescind. In August, Rogers told me that her real worry was less about the prospect of securing previously approved funding and more about how to contend with a potential ideological blacklist moving forward.

“It’s the fact that IMLS is gone,” she said. “It’s the fact that the National Endowment for the Humanities took away funding for incredible state-run projects to give it to nationalist projects that fit the president’s agenda—and put some of it into a sculpture garden. … Took funding away from libraries and reading programs for kids in order to fit some kind of agenda. The problem is that we won’t be able to apply for any of that stuff in the future.”

It all comes down to power and the control of extraction. Sacrificing certain people in certain communities in order to justify profit and capitalism.Banner

Rogers has commuted from her home in New Orleans to St. John for the past 11 years. She views the tale of industry, preservation, and now federal involvement in the parish as part of a single, shared thread. For most of the 1900s, laborers at Whitney and other estates in the parish tended to pay rent to live in former slave dwellings. When the owners of these plantations eventually sold their properties to oil companies and chemical conglomerates, those tenants had little to no say over it. Land was agency, and they, like their enslaved ancestors, had been locked out.

“[There’s] this idea that we should be done with the past,” Rogers said. “But the past is not done with us. Not even close.”

The Whitney estate was established in 1752 as a modest indigo farm by a German immigrant named Ambroise Heidel, who amassed at least 20 captives. By 1820, Heidel’s descendants had changed the spelling of their surname to Haydel, planted 300 acres of sugarcane, constructed a steam-powered mill, and enslaved at least 73 individuals. Within another generation, the captive population hovered around 100, and the estate produced 400,000 pounds of sugar annually.

Across surrounding St. John, chattel empires were cemented through vigilant tyranny. Bondage was first governed in Louisiana by the French “Code Noir”—a set of regulations outlining acceptable treatment of captives and punishment standards in the 1700s. Runaways, according to the charter, would have their “ears cut off” and shoulders “branded with” a fleur-de-lis. A second escape attempt came with more brandings and the severing of hamstrings; a third meant death. As the enslaved population exploded in the territory, a feeling of paranoia about rebellion escalated among the plantation owners. Right after the U.S. purchased Louisiana in 1803, the territorial governor wrote to then–secretary of state James Madison to express his concern about potential volatility in the region. “At some future period,” he cautioned, “this quarter of the Union must (I fear) experience in some degree the Misfortunes of Saint-Domingue and that period will be hastened if the people should be indulged by Congress with a continuance of the African trade.”

Along the eastern bank of St. John, this fear became reality on the morning of January 8, 1811. With stunning speed, a group of 300 to 500 enslaved laborers rose up with firearms and other weapons, killed two white men, and began to march downriver. Branded the German Coast Uprising, their ranks increased as the rebels roved from plantation to plantation. The combined forces of a local militia and the U.S. Army and Navy were required to drive them back for good. When the insurrection was finally quelled, authorities mutilated the renegades’ corpses. Sixty-six captives were killed in total—21 during the insurrection, 45 after. The heads of the rebels were then mounted on pikes.

The route for which their skulls served as decoration stretched all the way to New Orleans. It’s called the River Road.

V.

You could spot us from the two-lane highway. Ashley Rogers was fiddling with a doorknob at the entrance of an old general store at the Whitney Plantation. I stood in her shadow. The structure, which looks like a schoolhouse, is the most visible portion of the estate from the western River Road. Hinges creaked, and we stepped inside.

“This is the old manager’s office,” Rogers said, surveying the room. “We painted everything, but we kept where it had stuff written on the wall.”

The space smelled of wood sealant. Every floorboard was buffed to half-court polish. The whole setup felt like a portal to sharecropping’s peak: Glass cabinets with smooth-handled drawers were bathed in light that radiated down and off the neighboring sugar fields. Back when Whitney was transitioning from slavery to tenant farming, the workers on the plantation would come into this building and shop for groceries that they couldn’t grow on their own. Rogers told me that the museum is opening an exhibit in the structure soon.

We walked out, and I followed her along a gravel pathway until we reached a cluster of live oaks in front of the plantation’s big house. I asked how many staff members have ancestral connections to the estate. “It’s about a third,” Rogers said. “And that may be an underestimation.”

The main manor loomed ahead of us. It has three floors, supported by Creole-style columns, as well as a porch on the second story. The shingles on the roof are tinged orange, and the rest is painted white. Inside, a small tour group paced around the ground floor. Rogers told me that they’d removed all the furniture in the building to make visitors focus on the construction—the toil required to create the space. Each brick along the walls had been crafted by captive children.

Dotting the main pathway that bisects the plantation, a few misting stations flowed with cool water to combat the 93-degree heat. Beside one of these was a slave dwelling constructed of dark brown planks. On the other side of a short wooden fence, the old overseer’s cabin baked in the sun; close by, another slave dwelling sat off the pathway. Rogers told me that it and its sister cabin were the only shacks still standing on the property at the turn of the 20th century. Nearly all the folks who’d been enslaved at Whitney departed after the Civil War, but new arrivals from all over St. John replaced them as tenant farmers in the next century-plus. By 1969, the plantation was still in operation, growing 325 acres of sugarcane and another 550 of soybeans.

Once Whitney’s final resident-owner moved out due to old age, the estate fell into disrepair. In 1990, it was purchased by Formosa, the same plastics company that had scooped up some of the Banner family’s land in Wallace. It had planned to demolish the plantation and another nearby manor, but residents pushed back and the corporation sold the land to a local businessman, who’d go on to found the museum and bankroll it until 2019.

While standing in front of the restored slave cabins, I asked Rogers what kind of wood was used for the roofs. They’d begun to bristle and split. “Cypress,” she answered, slowing for a moment. “They were covered over with metal sheeting in the 20th century. These were the ones that people were still living in until 1975. We have a couple people who work here whose family members lived in some of these cabins.”

Toward the back of the property a pond undulated, and beyond that loomed more fields of sugarcane, ready for harvest. “I don’t know if this is going to be open,” Rogers told me, approaching a locked fence in front of the rows, “but we’ll try.”

I angled my face through a gap in the wiring. Endless lines of cane were on the other side, reaching back hundreds of yards. A darkness at the center of one cluster of stalks appeared so deeply green that it verged on blue. “I’ve studied slavery in books for a long time, but there’s no way to understand a [sugar] field without standing in it,” Rogers said behind me. “The plant is so much bigger than you, and you can’t see the end of it. It’s completely disorienting. The leaves, they crisscross over each other. You can’t see anything in there. The underbrush is full of snakes. When I was out there for the first time, I sensed the depth of the field in a way I hadn’t before. The unending labor.”

Even at a distance, the mass consumed my whole line of sight. Beforehand, Rogers had warned me of what taking in these surroundings tends to invoke: the sugar and the bygone shacks and those haunted spaces in between. You couldn’t put a price to it. “We’d all do better if we can all sit with this kind of discomfort,” she said.

“This is what I think about American history, and it’s what I think about our own personal families. It’s everything at the same time: It’s upsetting and sad—it’s also joyous. It’s numerically impossible for you to be related only to good people. You have too many ancestors.”

VI.

His worn hands the color of roux, Robert Taylor buttoned the top notch of a blue oxford, rose, and offered to show me some tombs. Most of Taylor’s family is buried in a graveyard on old sugar land in east St. John that’s been partly paved over and encircled by a Marathon Oil refinery. “If you’d like,” Taylor told me one sunny afternoon in mid-August, “I’ll take you.”

We cruised the River Road due west, passing old sugar lands that had been developed and rebuilt to serve new idols. I was behind the wheel. In a few minutes we reached the inactive neoprene facility managed by Denka, the synthetic rubber conglomerate at the heart of the community’s dispute with the EPA. Thin smokestacks and ventilation structures protruded from the factory like cascading levels of a microchip. While I pulled over to snap a few photos, Taylor said what frightens him now that the company has paused operations is the residual impact of past emissions. Even if Denka’s facility closes for good—no guarantee, given the Trump administration’s choice to drop all litigation against it—a disposal effort would need to be completed, in addition to continued community health monitoring and care.

While St. John as a whole is 56 percent Black, the population within a mile of the neoprene facility is 94 percent Black. “What are they going to leave here?” Taylor asked. “What’s going to happen to us? The aftereffects of what they have done already.”

Cancer Alley contains upward of 200 petrochemical plants. Taylor’s environmental nonprofit, Concerned Citizens of St. John, filed multiple petitions with and lawsuits against the EPA into the 2020s, but it wasn’t until the Biden administration came into office that the agency took concrete steps to address their fears of pollution in the parish. The state of Louisiana, for its part, responded to a civil rights inquiry by Biden’s EPA by hiring two chemical company lawyers as official counsel. The probe was ultimately dropped.

While Taylor and I continued coasting along the River Road, my mind kept wandering back to this precarious arc. After a wide bend on the thoroughfare, a grain terminal emerged, so tall it eclipsed the levee and countryside below it. “Remember we talked about the sugar refinery?” Taylor said, referring to where his parents had worked. “That’s the original site.”

[There’s] this idea that we should be done with the past. But the past is not done with us. Not even close.Ashley Rogers, executive director of the Whitney Plantation museum

The main building in the complex was connected to a row of tanks via tubes and piping that gave it the appearance of a concrete automaton. Within 100 yards, the smell hit. It was sharp and sour and hung about in the car. There were undertones of fermentation, but at a scale that felt wholly unnatural.

“It’s terrible,” said Taylor, noting the scent. “The Port of South Louisiana purchased this.”

I asked him what it produces.

“They don’t make anything,” he said. “People are [just] storing shit.”

Conveyors stretched out to the river. A hundred yards past the complex, we turned down another gravel road, which Taylor told me was once part of a neighborhood. “This was the main street,” he said. “They had white homes and businesses right here.” Today, only a few houses occupy the space, almost all inhabited by Black families. “This is where the Black community was started. And I used to live right up the street,” Taylor said, overlooking a cluster of chemical tankers. “None of these plants were here. None of these tanks.”

Five sets of railroad tracks rusted on gravel at the end of the lane. The Marathon Oil refinery and the graveyard we’d come for stood a few hundred yards beyond that. The scent in the air shifted. It was now utterly inorganic. A faint whiff of gasoline, only much stronger, almost painful to inhale. It was a smell that burned and kept burning. The effect compounded.

The refinery swallowed the horizon. We angled the car back toward the highway and retraced our path. The old, sour fumes flooded in through our air vents the closer we got to the River Road. I’d lost track of where each scent had originated. I asked Taylor whether we were smelling grain, gasoline, or something else.

“Hard for me to tell,” he said, turning to the window. “Got a couple of plants around here.”

VII.

“A Scot named Law, gambler by profession and suspected of evil intentions toward the king,” the police chief warned the French foreign minister in 1714, “appears at Paris in high style.” These were the waning years of Louis XIV—the monarch who’d plunged France into five wars and claimed sovereignty over half a continent an ocean away. The “Scot named Law” went by John. He was a cardplayer and philanderer who had bought an elegant townhouse in Paris’s first arrondissement with money that folks figured he’d pilfered. A financier by trade, Law was also old pals with the king’s nephew, the Duke of Orléans.

John had many ideas about how to kick-start France’s lagging economy and just as many about how to line his pockets. In 1717, the duke, then regent of the entire French empire, gave Law and his company control over trade with its New World colonies—including a vast expanse of North American wilderness known then as La Louisiana.

As part of its deal with the French government, Law’s organization was charged with luring settlers to the territory. The same year, he heard a proposal from a Swiss man, Jean-Etienne Purry, who was looking to transport hundreds of European emigrants to Louisiana as laborers. With complete control over the colony, Law hired Purry and sent him to convince thousands of yeomen across western Germany and Switzerland to move to Louisiana as engagés, a class of indentured servant.

In mountain villages, they dispersed brochures touting the territory as “a land filled with gold, silver, copper, and lead,” with “an extremely pleasant soil.” In May 1719, Law granted himself property holdings in segments of the colony: one in Biloxi, in present-day Mississippi; another up in Arkansas; and another at English Turn, a short distance south of New Orleans. From these stakes he’d pledge some 1,600 migrants land for new homes.

In little time, Law’s engagés were left to discover that the covenants for their new foundations were inscribed in blood. During a year spent languishing at cloistered French ports, waiting for departure, hundreds of these would-be settlers died of what was likely scurvy. By January 1721, four ships had finally set out for Law’s Biloxi holding. Along the journey they were again decimated by disease: Of the 862 engagés on board, only 200 arrived.

Countless more perished in their first few months at the settlement, their ranks further culled by lack of clothing, food, and medicine. Eventually, the group abandoned Biloxi and ventured west. The haggard engagés trekked their way along the gulf, down to New Orleans, where they petitioned the governor of Louisiana to take them back to France. He declined. Instead, he offered them land grants north of the fledgling city, in an area they’d call Les Allemands—in English, the German Coast.

The new outpost sat on the banks of the Mississippi, an expanse described by a company official as “land which in its entirety has never flooded.” By 1722, the population had bloomed to a few hundred across four villages. “As these people are very hardworking, there is reason to hope that this year they will have an abundant harvest,” an inspector wrote that spring. Within months, the land they’d been assured had never flooded coursed with alluvial currents, 8 feet high.

The first hurricane in French Louisiana’s history razed all but one of the German Coast settlements. Catastrophic winds lasted 15 hours; rainfall and residual high tides lasted for five days. When the storm headed east, the only upright village—the last standing dream that untold engagés had died for—sat on the western bank of a parish later christened for a saint with the same name as their tempter.

In the story of St. John, it is hard not to believe that things sometimes happen for a reason and that those reasons sometimes happen to be malicious. Thousands of serfs lost much blood for a patch of dirt; their children and grandchildren proceeded to spill much, much more to fashion a different patch as a launchpad for their delusions. That the engagés’ journey from swindled to wounded to resigned and re-tempted would be followed by three centuries of unholy covenants—the flesh trade, debt peonage, rampant industrialization—is both what distinguishes St. John from the country at large and what makes the parish such a faithful analogue to it. None of these sins are distinct to the region, but precisely how they’ve amassed here is.

It’s numerically impossible for you to be related only to good people. You have too many ancestors.Rogers

Roam the roadsides for long enough, and the marks of all these bloody compacts accumulate in plain sight. You can spend hours driving up and down the River Road and go no more than three minutes without spotting some sort of chemical plant, oil refinery, or towering grain terminal. The names stack like sediment: Stockhausen Superabsorber, Nalco, Evonik, Pinnacle Polymers, Southern Chemical Industries, Bayou Steel Group, Apex Oil, Shell Oil and Gas, Marathon Oil.

Exhaust vents and crop conveyors line the byways, expelling cumulus vapors and endless dust clouds. Buzzards circle the wheat and corn terminals, scouting unseen carcasses shrouded in the shadows of concrete superstructures. Commerce seizes the air—some aromas resemble a deep rot, others are closer to burning rubber. There are nearly 50 different toxic chemicals breathable at any moment in St. John. That reality, like the vultures and onslaught of nauseating scents, is a calamity and a mark of carnage if ever there were one.

On the east side of the river, again and again, I saw a quiet death rising out of evaporation pits, ventilation shafts, and steam pipes. Practically imperceptible but—with enough time and misfortune—lethal nonetheless. On the other side, these airborne terrors were accompanied by the residue of sugar fiefdom and bondage. Vast, emptied cane fields were still dotted by intentional burn marks. Tangles of stalks crested at heights beyond those of the pickup trucks that impatiently patrolled them. Plantation manors and shacks with satellite dishes and arpents parceled to oblivion gathered moss, dust, flood stains.

Across St. John I witnessed the costs of one age stacked on the costs of another, and another before that.

Many forces have ruled over this land since it was snatched from the Chitimacha: French and Spanish ones, Southern and Northern ones, local and national ones. But in every iteration of St. John the Baptist Parish, its most enduring feature has been that it is a place of ruthless competition. A site where one life is liable to be clawed out at the expense of another. Perhaps nowhere else in America is such an ethic laid so starkly bare. Perhaps nowhere else is that ethic as essential to understanding our national history and identity—despite what any political figureheads or attempts at sanitization may suppose.

Even with the levees, along the River Road, wreckage is inescapable. In that neck of Louisiana, the costs of American figments tend to collect, vaporize, and seep out from the dirt.

VIII.

We entered through an opening in the sugarcane palisade and drove until we hit the lone patch of grass in a maze of pipelines, tanks, and towers. I turned onto the modest plot of Zion Travelers Cemetery in east St. John. Robert Taylor swung his legs out of my rental car and hoisted himself up. Then he paced toward the shadow of the oil refinery where his mother, siblings, and father are not quite 6 feet deep.

The tinge of crude petroleum blanketed the air. The mud clung to our soles. A film of rust-hued debris coated the looming overground tombs. Taylor swiveled his head from left to right, scanning the headstones. He was looking for his family’s remains. “I don’t know if I can find them,” he warned me delicately. “I’ll try.”

Zion was established well before Marathon Oil scooped up the surrounding property. (The oldest tomb I encountered listed the year of death as 1881.) The aged headstones were chipped and faded; the newer ones appeared to be sinking into the earth. Even from the front of the grounds, right near the entrance, so many of them were in such close quarters. So few held folks who had made it beyond 60 years of age.

Steam exited the chrome ventilation shafts beyond us. The whole campus formed its own skyline. The adjoining parking lots were larger than the cemetery—the human toll of one era in the parish, overshadowed by the sprawl of the next. Bygone tombs spilled out from the mire.

I worked my way up to asking Taylor whether he planned to be buried there.

“My kids don’t want me to,” he admitted, after a little prodding. The family has a plot picked out at another graveyard where his wife of 61 years, Zenobia, is entombed.

“They bought a double one so that I could be buried with her,” he said, with a touch of trepidation. “I kind of wanted to be up here. My mom and my dad. My grandpa, my aunts and uncles and cousins. Aw, man, so many people, man.”

I nodded my head, and the churning of the refinery stole the quiet. “They hate the idea of me being next to the thing,” Taylor continued. “They hate the idea of me being over here with this plant.”

We circled the plot a few more times but still couldn’t find his family’s headstones. Taylor wandered off after a while and called his cousin—a modestly tall caretaker for the graveyard, with a thick bayou accent—who, within minutes, pulled into Zion, exited his truck, and took us toward the back of the burial ground. A shift change at Marathon had ushered out a cluster of workers into the nearby parking lots. The crypts in the interior of the cemetery were stacked, literally, atop one another—three or four at a time. There were whole sections where the morbid towers extended high enough to obscure the sight of the refinery.

When we reached the family plot, Taylor’s mother was positioned atop her own daughter and mother. The two cousins approached their relatives’ remains. Steam billowed out from the city of pipes to our east. Sugarcane danced in the wind to our west. St. John the Baptist mud held the whole mangled calamity in place.

Robert Taylor gestured to his dead kinfolk.

“You see?” he said. “This plant done come here now. They can’t go back any further.”