Can Sam Darnold Go Where No Reclamation-Project QB Has Gone Before?

Over the past two years, Darnold has shown he has what it takes to be a good regular-season quarterback. But for Seattle to fulfill its potential this postseason, he’ll have to move beyond feel-good story and become a true franchise passer.

When Sam Darnold met with Seattle media for the first time last spring, he was asked to explain how he had turned his career around in Minnesota. Before his time with the Vikings, Darnold was thought of as an exciting but mistake-prone quarterback, one who won just 21 starts over his first six seasons. But in his lone year in Minnesota, he threw for 35 touchdowns and over 4,300 yards. Darnold credited one person for convincing him to make a crucial adjustment to his playing style. It wasn’t Kevin O’Connell, or Kyle Shanahan, or any other coach he’d had. It was 49ers quarterback Brock Purdy, who started ahead of Darnold in 2023.

“I really thank Brock a ton,” Darnold said in his introductory press conference a few days after signing a three-year, $100.5 million contract with the Seahawks. “For just his style of play and how he described his style as like, we’ve got a ton of great playmakers on offense.

“Like my job is just to play point guard. … When I changed my thought process as a quarterback to kind of just getting the ball in my guys’ hands, that’s really where it unlocked for me.”

Darnold started doing more by trying to do less. When he played football in high school and college, he found it easier to make plays for himself rather than relying on his teammates. “Like if a concept wasn’t there, I was sort of eager to run, get out of the pocket,” Darnold said. But when he got to the NFL, “it’s not that easy. I think that’s where the troubles came a little bit early in my career—just thinking I could run around and make plays if something wasn’t there.”

Darnold had to reject the style of play that had convinced the Jets to draft him third overall in 2018. It just wasn’t working. He could make many of the superstar plays you’d see from Patrick Mahomes and Josh Allen, but not as reliably. Mistakes piled up and he was eventually run out of New York—and then Carolina. After two seasons with the Panthers, Darnold signed a backup deal with San Francisco, where he met Purdy and received career-altering advice. The point guard mentality has served Darnold well over the past two seasons. He’s followed up his breakout campaign in Minnesota with a validating season in Seattle. Darnold finished fifth in passing and tied for the league lead in yards per dropback in 2025. He made his second Pro Bowl and led the Seahawks to a 14-3 record and the top seed in the NFC.

But while this season has been another success for Darnold, his numbers have trended in the wrong direction as of late. After finishing the first half of the season ranked near the top of the league’s statistical leaderboard in categories like expected points added and success rate, Darnold’s production has bottomed out over the past two months. Only five quarterbacks have lost more expected points on dropbacks than Darnold has since Week 10. And after averaging 9.1 yards per dropback over the first nine weeks of the season, he averaged just 6.6 yards the rest of the way.

Over the past few seasons, the NFL has seen several quarterbacks find their footing following rough starts to their careers, either with new teams or under new coaching staffs. Jared Goff became a highly-paid star in Detroit after Sean McVay gave up on his development in Los Angeles. Baker Mayfield left Cleveland and eventually found a home with Tampa Bay, where he’s often produced like a top-10 quarterback. Like Darnold, Geno Smith became a Pro Bowler in Seattle after flaming out with the Jets. Tua Tagovailoa was benched several times during his first couple of years under Brian Flores before Mike McDaniel turned him into a productive quarterback (at least for a time). Daniel Jones was putting up career numbers for a historically efficient Colts offense in 2025 before a season-ending injury. These examples have often raised the question of whether NFL teams are too quick to give up on young quarterbacks.

But while these reclamation projects are feel-good regular-season stories, they don’t often progress beyond that. The Bucs have averaged only nine wins in Mayfield’s three seasons in Tampa. Goff got the Lions within a game of the Super Bowl in 2023 but couldn’t finish the job and went one-and-done in the playoffs last season when Detroit was the favorite to win it all. Smith and Tagovailoa never won postseason games. Jones didn’t get a chance to show he could.

Now, having already added his name to the growing list of quarterbacks who have redeemed themselves after being dismissed as busts early in their careers, Darnold is trying to graduate from reclamation project to true franchise quarterback. Last year in Minnesota, his redemption story followed the same script as the others: He threw for just 166 yards on 41 attempts in a Week 18 loss to the Lions with the division and a first-round bye on the line. The following week in the wild-card round, he took nine sacks against the Rams in a season-ending loss. Now, with the Seahawks entering the postseason as the favorites to win the Super Bowl, Darnold will get another chance to show that he is different from those other quarterbacks. Whether he’ll be able to take advantage is another question.

Not every failed quarterback can be salvaged. Some just don’t have the talent or work ethic to cut it as an NFL starter. But in order for a passer to be built back up, they need to possess a foundational trait or skill that a QB-friendly coach can construct an offense around. In Detroit, under Ben Johnson, Goff found a system that protected him from pressure, which allowed him to show off his next-level timing and accuracy from a clean platform. Mayfield got a similar deal in Tampa Bay. McDaniel saw Tagovailoa’s feel for making anticipatory throws over the middle of the field and designed the entire offense around it. Shane Steichen built a successful passing game around Jones’s downfield throwing ability. If you’re going to find success as a more limited quarterback, you need a thing. You need a gimmick.

When Seahawks offensive coordinator Klint Kubiak was asked what stood out in Darnold’s game, “mobility” was one of the first traits he listed. Kubiak wasn’t talking about Darnold running the football. He meant the QB’s ability to throw on the run, especially after carrying out a play-action fake.

“[It] definitely stands out on tape,” Kubiak said in March. “Seeing Sam turn his back to the defense and find deep crossers and hit guys in stride, is definitely a strength of his game … throwing on the run.”

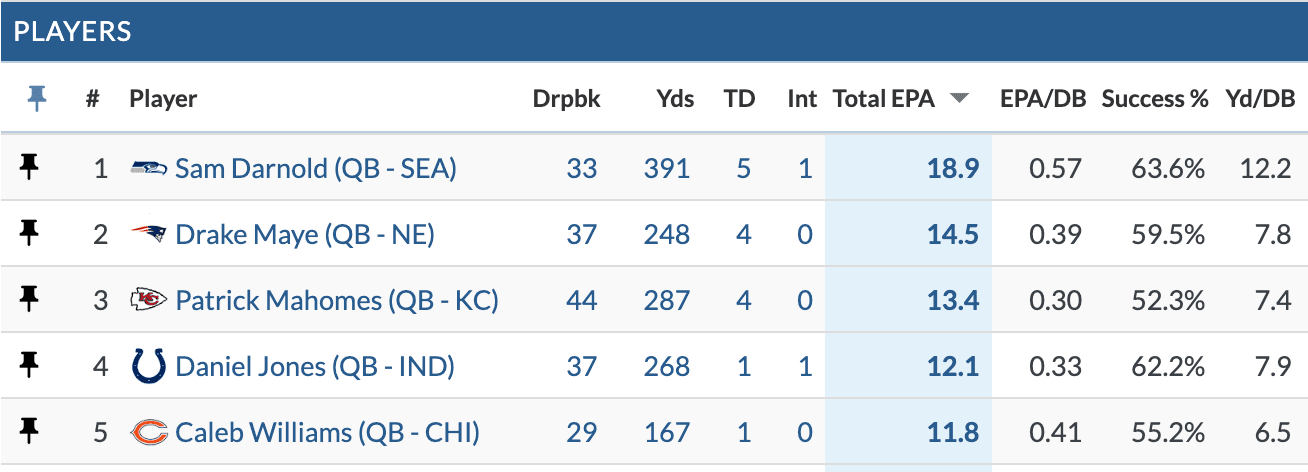

Darnold also mentioned Kubiak’s use of “play-action keepers” when discussing how the OC’s system suited his game. Kubiak operates a version of Kyle Shanahan’s offense, which is built around an under-center run game and play-action fakes off of similar action. If leveraging Darnold’s ability to throw on the run was a big part of the pitch that brought the free-agent QB to Seattle, then the coaching staff has made good on the promise. No team got more out of those play-action keepers, or bootlegs as they’re commonly referred to, than the Seahawks did early in the season. Through 11 weeks, Darnold led the NFL with 18.9 EPA generated on 33 bootleg dropbacks, per Pro Football Focus and TruMedia. Darnold averaged a ridiculous 12.2 yards per dropback with a 63.6 percent success rate on those plays. The gap between the Seahawks quarterback and the rest of the league was significant.

That wild level of efficiency wasn’t the only thing that made Seattle’s bootleg game unique, though. Darnold throws with his right hand but has an uncanny ability to make passes while moving to his left. Most right-handed quarterbacks aren’t comfortable making throws across their body, so the majority of bootlegs are designed to go to the right side of the field. Since 2021, there have been just over 4,000 bootlegs called across the NFL, and only 999 of them have gone to the left side of the field. Because of that, boots to the left are generally more deceptive when they’re run, which leads to greater efficiency.

So having a quarterback who can boot in either direction can really boost your play-action game. In 2025, Darnold was the only right-handed starter who finished the regular season with more bootleg dropbacks to the left than bootlegs to the right. He finished second in left bootleg dropbacks behind only Tagovailoa, who is a lefty quarterback. Those weak-handed boots by Darnold caught the league off guard early on. Through 11 weeks, he generated 11.0 EPA on 21 dropbacks and was averaging 13.6 yards per play.

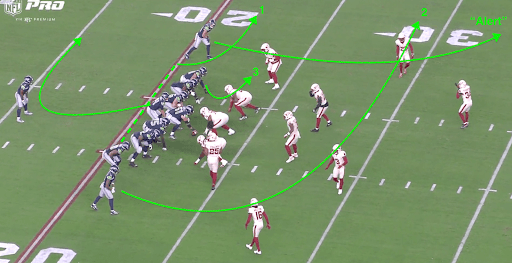

Though the Seahawks ran these plays out of different formations and with different personnel groupings, the route combination was typically the same. A receiver to the side of the fake would run a deep, vertical route designed to clear out the defense. A receiver from the opposite side would run a crossing route at an intermediate depth, and a third option would work to the strongside flat, giving Darnold a three-level read.

The deeper route is typically viewed as an “alert,” meaning the quarterback only takes it if the defense gives him an inviting look before or directly after the snap. The real first option is the flat route. If that’s not open, the crossing route typically is. As Kubiak mentioned at Darnold’s introductory presser, the Seahawks quarterback can hit those crossers as well as anyone in the league—and I’m not sure there’s a right-handed quarterback better at making them while moving to the left.

But there’s a reason I’ve been using Week 11 as a cut-off for these statistics. This is the NFL, after all. And if an offense is killing defenses with a particular concept, teams will eventually snuff it out. While Darnold ended up leading the league with 359 yards on bootleg dropbacks to the left this season, the efficiency of those plays took a nosedive down the stretch. After leading the league in EPA on those plays through the first 11 weeks, he finished dead last in the same category over the final seven weeks.

Late in the season, defenses made more of an effort to attack the left edge to prevent Darnold from getting out to the perimeter where he would have plenty of time and space to find an open receiver. But it’s kind of odd it took defenses three months to catch on when, in Seattle’s Week 2 game in Pittsburgh, the Steelers came up with that solution after getting burned twice early in the game. They sent a blitz off the left edge the third time they saw that look, and Darnold panicked and threw a tipped interception. Pittsburgh sent the same pressure the fourth time, which resulted in another panicked throw for Darnold. The four-play sequence was a microcosm of how the season would go. The first play results in an easy throw to the flat for a chunk gain:

On the second play, Darnold finds the crosser for another solid gain:

Finally, the Steelers adjust and blow the play up twice:

As Darnold’s production on bootleg plays has declined, his overall production has followed. Since Week 10, he ranks 26th in overall EPA per dropback. That’s mostly due to an increase in turnovers: He’s thrown nine interceptions and lost four fumbles since the midway point of the season. His 13 turnovers lead the league over that span. Darnold’s average time to throw is also up, which has led to an increase in sack and scramble rates. As defenses have taken that foundational concept away from Seattle, we’ve seen more shades of the old version of Darnold—the one who thought he could run his way out of plays gone awry rather than relying on the point guard mentality.

And Darnold and the Seahawks are about to face a defense that’s intimately familiar with their game. They’re taking on the 49ers for the third time this season on Saturday. And should the Seahawks make it to the conference championship, they may see another NFC West foe in the Rams for a rubber-match game, after the teams split their two regular-season matchups.

Navigating this playoff field will be the biggest challenge of Darnold’s career—but it also comes with an opportunity to show that he’s not just a reclamation project whose success is predicated on a comfortable offensive environment. Comfort is difficult to find in the playoffs. Opponents have a season’s worth of tape on you. They know all of your team’s tendencies. They know all your strengths and weaknesses as a player. They have a good idea of how to make a quarterback nervous. So many of these reclamation stories haven’t had satisfying endings because those quarterbacks had their flaws exposed when they were forced out of their comfort zones. Goff’s mistakes under pressure led to Detroit’s demise. Mayfield has turned the ball over while trying to do too much. Tagovailoa’s inability to create cost him in his only playoff game in 2023. Smith lost his lone postseason appearance for similar reasons.

In his final game as a Viking, a 27-9 loss to the Rams, Darnold took a ton of sacks, and many of them were on him. Los Angeles took away the deep passing game, and instead of playing point guard, Darnold held on to the ball and waited for a big play to present itself. It was a crappy way to end what had been the best season of his career. One of the first things he was asked at the beginning of his Seahawks career was about how things ended in Minnesota.

“I was waiting for someone to bring that up, by the way,” Darnold joked. “I appreciate that. It’s fair … I learned a ton from those last two games playing Detroit and playing L.A. … I felt like I was taking some unnecessary sacks last year, especially those last few games.”

The last two regular seasons have shown us that Darnold can perform when he’s comfortable. But if he’s going to be more than just a redemption story—if he’s going to be a true franchise quarterback that Seattle can build a future with—he’ll have to show that his late-season slide wasn’t a precursor to the ending these reclamation stories typically have in the playoffs.