I can’t decide whether it’s criminal or poetic that news of Bob Weir’s death broke on a Saturday night. If he had any say in the matter, I suspect Bobby would have kept it quiet until at least the following morning and let word slip early enough so as not to overly harsh the vibe for that evening’s festivities. (Deadhead rule no. 1: Never miss a Sunday show.)

Alas, the cofounder of the Grateful Dead—who passed away at age 78 due to complications from cancer—lived an extraordinary American life. Started one of the most successful, longest-running, and all-around greatest rock bands at the age of 16. Dropped acid with Ken Kesey and Neal Cassady and the rest of the Merry Pranksters along the way. Had adventures in all corners of the globe, from the grandest pyramids of Egypt to the dingiest dives of New Orleans to the second- and third-tier hockey arenas of this nation’s hinterlands. Wrote and performed enduring songs in an interpersonal group environment that can be charitably described as “chaotic” (and perhaps more accurately as “toxic”). Honed the finest set of legs seen on any heterosexual white man in the mid-to-late 20th century (so fine that The New York Times devoted an entire article to it this weekend). Changed music and the world in ways that are vast and all-encompassing and plainly obvious (as well as small and niche and subtle). And made it possible for millions upon millions of people—living and no longer living, friend and stranger, Deadhead and “I like that one song about the cokehead train engineer”—to have a really, really good time.

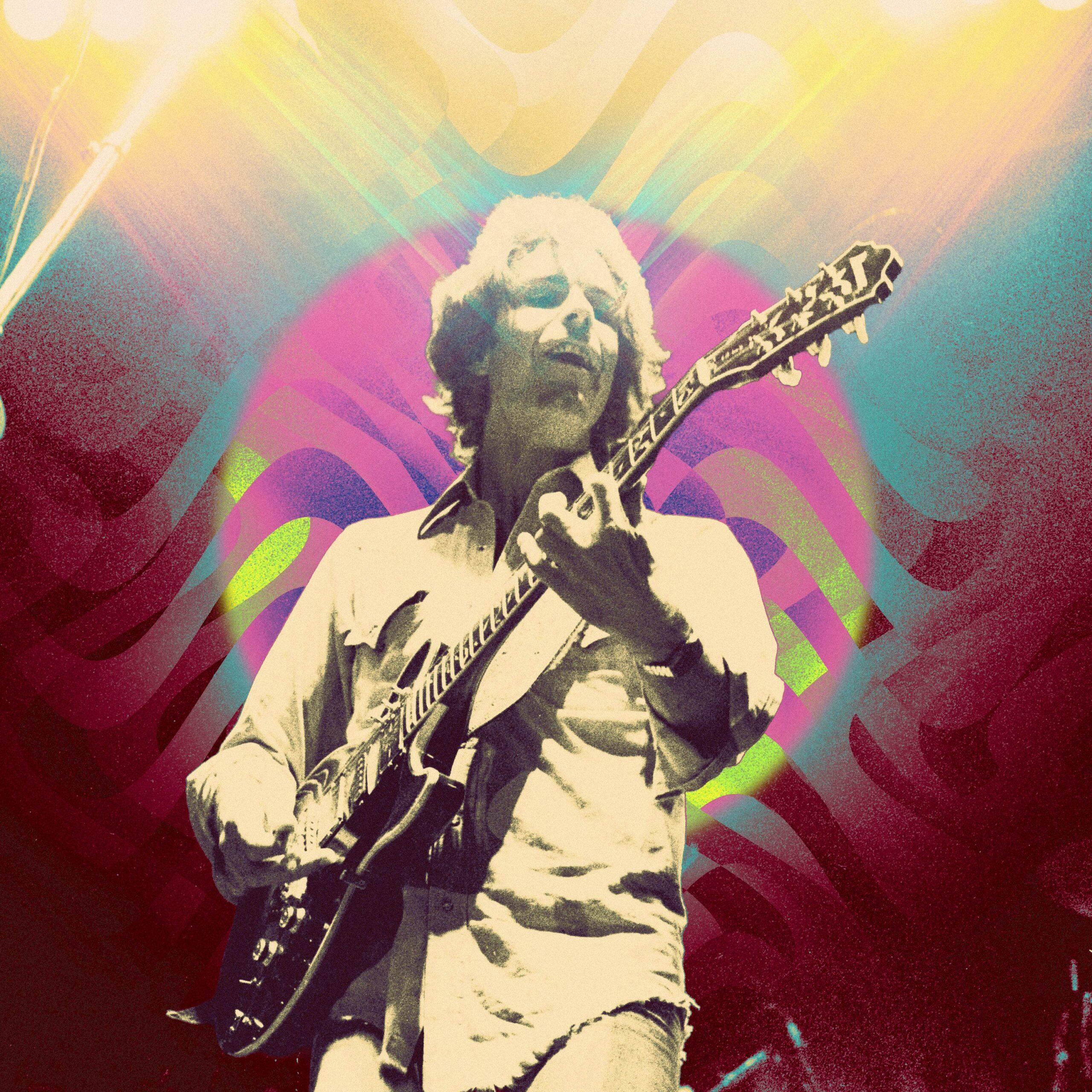

That last point is most important. At least, I imagine, it was most crucial to Bobby. “The chances are I spent more time standing onstage playing guitar and singing than any human who ever lived,” he says in the 2014 documentary The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir. It’s hard to confirm the veracity of such an assertion, though the breadth of Weir’s onstage life is considerable. It stretched from 1965—when he cofounded the Warlocks with a Palo Alto bluegrass enthusiast five years his senior named Jerry Garcia—to 2025, when Weir’s highly lucrative post–Grateful Dead project Dead & Company headlined a weekend of shows in San Francisco celebrating the band’s 60th anniversary. Upon his death, it was revealed that Weir had already been diagnosed with cancer at the time of those San Francisco shows, though he kept that quiet. (Again, one must not spoil the gig.)

Of all the countless days he was onstage, with his guitar, inspiring crowds to dance (or sway or spin or rock back and forth or freak out or whatever the hell else you wanted to do at a Dead show), the most sanctified part of the week was Saturday night. He wrote about it in holy terms in “One More Saturday Night,” which debuted in Dead set lists in 1971 and on Weir’s solo debut, Ace, the following year. The rare Dead song attributed solely to Weir—the band’s frequent lyricist, Robert Hunter, apparently took his name off it after feuding over Weir’s changes—sums up his worldview almost perfectly. It’s not his best song (that’s either “Jack Straw” or “Playing in the Band,” two more Hunter collaborations). Or his most popular (“Sugar Magnolia,” again with Hunter). Or his most important to the Dead’s overall aesthetic (the early jam showcase “The Other One”). Or his most moving (“Cassidy,” composed with his old prep-school chum John Perry Barlow, and performed best as a duet in the ’80s with Brent Mydland). Or his most underrated (“Black Throated Wind,” weirdly the first Dead song I ever loved, from a tape recorded on the spring ’91 tour, of all tapes). Or the sleaziest (“Mexicali Blues”). Or the most bonkers (the awkwardly titled skronkfest “Victim or the Crime”).

“One More Saturday Night” is simply the one that’s most definitively Bobby. It functions as a kind of origin story retrofitted to Chuck Berry chords. Born in 1947, Weir was given up for adoption by two college students in their early 20s. He was subsequently raised by a nice suburban couple amid the well-to-do environs of San Mateo County. Destined for a boring, Eisenhower-era existence, he instead received “a mighty sign / written fire across the heaven, plain as black and white / ‘Get prepared, there’s gonna be a party tonight.’”

As a rock critic, I was required to care about the Grateful Dead. Their foundational importance to American culture goes beyond whether you like their music. (It’s like when someone tries to argue that the Beatles are overrated—No, you just don’t care for “Hey Jude,” which is your right. But their centrality is a plain fact that’s bigger than your or my taste.) In terms of Weir’s specific contributions, his embrace of country music and the integration of Johnny Cash and Marty Robbins standards into the Dead’s repertoire are core threads of whatever “Americana” means now. More broadly, the Dead were always forward-thinking when it came to anticipating shifts in the music business and the ways those changes are shaped by technology. That carried on right up until the end of Weir’s life, when Dead & Company were making a fortune streaming live video from the road and playing “Touch of Grey” in front of a 160,000-square-foot high-definition screen at Sphere in Las Vegas.

But as a fan, I didn’t become a full-blown Deadhead until the COVID-19 pandemic. Right before shutdowns were instituted in March 2020, my friend Rob and I started a podcast where we went through the 36 volumes of Dick’s Picks, a series of Dead concert archival albums. I originally conceived it as an excuse to dig deeper into a band I liked but didn’t know a lot about while also hopping on Zoom and socializing with a buddy on a regular basis. As the show unfolded, the band’s dynamic became readily apparent—Jerry was the heart, Phil Lesh was the brains, Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart were the engine, and Bobby was the spirit, the joie de vivre, what those who prefer gendered nomenclature would call “the balls.” That also made him ripe for our jokes. You can’t really make fun of Jerry (unless you’re the sort who spits on the Mona Lisa), and ribbing Phil isn’t as much fun because Phil was just less fun in general. But Bobby’s comedic fodder was endless—the shorts; the muscle shirts; the various ponytail eras; the corny blues covers he trotted out every night (usually in the set list’s third slot, if we’re talking ’80s Dead); his intensely committed hamminess when delivering Bob Dylan songs (or his own); his anguished, romantic caterwauling at the climax of “Looks Like Rain”; the way he purred “silky, silky, crazy, crazy night” on “Feel Like a Stranger” from 1990’s Without a Net; the entire Bobby and the Midnites oeuvre; and so on.

Lest it should be said: I love all this stuff. I am a firm believer in the idea that truly appreciating an artist or band means reveling in all aspects of their work, even the things you might initially scoff at, while also recognizing the ridiculousness of those attributes. (If I can impart any wisdom to our young generation of online stans, it’s that laughing at your heroes sometimes rather than reflexively defending them at all costs will make you happier in the long run.) For anyone to be an all-time great, they must have enough personal belief, guilelessness, creative and personal freedom, and extreme fearlessness to transcend the self-consciousness and intolerance for embarrassment and failure that hamstring 99.9 percent of the population. No band personifies this idea better than the Grateful Dead. And no member of the Grateful Dead embodied it more than Bob Weir. The greatness intertwined with goofiness, the silliness inseparable from the spiritual, the guy who was part saint and part Sammy Hagar.

This was acknowledged even within the Dead, with Bobby perpetually cast as the “kid brother” figure to Garcia and Lesh. Early on, they both castigated Bobby for his eccentric guitar playing, which for a while imperiled his permanent status in the band. Over time, however, they came to value how his irregular riffs (for a rock band, anyway) formed a glue between their own florid, showstopping jamming. Weir has said he was inspired by how McCoy Tyner’s piano playing complemented the lead saxophone on John Coltrane records, and he set about applying those lessons to his accompaniments to Garcia’s brilliantly beautiful solos. For anyone bound and determined to be worshipped as a conventional guitar hero, it was the opposite of a successful approach. But those obsessed with unconventional guitar playing locked into the strange, wondrous sounds that Weir routinely coaxed out of his ax, which even in the band’s stadium-rock years amounted to some of their most genuinely avant-garde elements.

A running bit on our Grateful Dead podcast was about their lack of sentimentality in the wake of losing friends, collaborators, and even bandmates. If there was a show that happened to take place around the death of a famous rock star, like Janis Joplin or Duane Allman, we would scan for any mention or tribute. And it never came. Not once. At best, you could strain your ears during “Not Fade Away” or “He’s Gone” and speculate on whether a notably impassioned vocal on a particular lyric denoted a stealth expression of grief. Maybe it did. But probably not. The Dead were just not that kind of band. During their 30-year run, they lost a different keyboard player to tragic circumstances every decade or so, and they always immediately returned to the road with a replacement. Men will overlook multiple dead bodies in their midst rather than go to therapy, blah blah blah. But it’s just how it was. Ending the band or even taking a year off was out of the question. “The Music Never Stopped” was not just the name of a Grateful Dead song; it was their animating philosophy.

And Bob Weir had a lot to do with that, too. After Jerry’s death in 1995, it was reasonable to assume that the Grateful Dead were also finished. And, for many diehards, they were. But Weir was only 47 at the time, still a relatively young man. (Virtually the same age I am now, so take that with a grain of salt.) Besides, it’s not as if Saturday was suddenly removed from the calendar once Jerry left this world. At a Dead show, the audience is at least as important as the band, and the Dead’s audience proved to be remarkably resilient no matter the changes in culture and music everywhere else. They were told there was gonna be a party tonight, and they expected a party tonight. So, there was gonna be a party tonight.

In 1998, the first post-Jerry iteration of the Dead hit the road. They were called the Other Ones, a nod to both Jerry’s preeminence and Bobby’s own status in relation to the fallen icon. Over the next 15 or so years, there were other assemblages featuring Weir and a revolving cast of Dead regulars and Dead-adjacent auxiliary players: the Dead; Furthur; Weir’s side vehicle, RatDog. But the Garcia-less Dead didn’t reach critical mass until the Fare Thee Well concerts in Santa Clara and Chicago in 2015. A return to the stadium-rock extravaganzas of the ’80s and ’90s, these 50th-anniversary gigs celebrated the so-called surviving “core four” of Weir, Lesh, Kreutzmann, and Hart. (A boys’ club to the end, they didn’t invite Donna Jean Godchaux, a member of the beloved ’70s lineup, who passed away in 2025.) This was ostensibly a series of “farewell for good” shows, but the publicity for Fare Thee Well teed up the unveiling that fall (just over three months later) of Dead & Company, a Frankensteined version of all the previous post-Jerry lineups (sans Lesh) that also featured John Mayer in the role of GQ-ed Garcia. For the next decade, they were one of the most popular touring bands on the planet.

Purists scoffed, of course. But they missed the point. That mighty sign, written in fire across the heavens, plain as black and white, it was still there, telling us to get prepared: There’s gonna be a party tonight. And the party always takes precedence. The music never stops. Not even for Bob Weir.

In the Facebook post announcing his death, Weir’s daughter Chloe said her father “often spoke of a three-hundred-year legacy” of the Grateful Dead and that he was “determined to ensure the songbook would endure long after him.” Weir himself reiterated this to Rolling Stone in 2025—he saw Dead & Company carrying on after he was gone and declared that his side-project band, Wolf Bros, was “constructed so that anyone can step in and do it.”

And so it shall be. Saturday will return next weekend, and some version of the Dead will be back on the road in the foreseeable future. You can literally set your watch to it. Maybe even by this summer, at your local neighborhood shed, where there’s a lawn big enough for dancing and drum circles. As for Bob, I think about that verse in “One More Saturday Night” where he imagines “God way up in heaven” creating the planet Earth as “a big old party,” which presumably peaks right before His day of rest, Sunday. “Don’t worry about tomorrow, Lord, you’ll know it when it comes,” Bobby sings. “When the rock and roll music meets the risin’ planet sun.” The sun will keep on risin’, surely. It will just be a little less bright without Bob Weir.