There are traitors, and then there’s Wu Sangui.

In 1644, a Manchu army gathered outside the Great Wall of China at the Shanhai Pass, the choke point on the only traversable route from Manchuria to Beijing. The Ming Dynasty, which had ruled China for almost 300 years, was in turmoil. An army of peasant rebels had captured Beijing. The emperor had hanged himself. Chaos was spreading. The Manchus, who’d long dreamed of seizing control of the empire, tapped the “Why not us? Why not now?” sign in their locker room and rode out. But to reach the capital, they had to make it through the pass, which was blocked by the Great Wall and protected by a Ming army of 60,000 soldiers led by the general Wu Sangui.

Wu had two choices. He could do his job and defend the pass, or he could switch sides and join the Manchus, ensuring his own survival but also ensuring that the enemy would conquer China. On May 22, 1644, Wu opened the gates and let the Manchus through. Two weeks later, the army had rolled into Beijing and established the Qing Dynasty, which ruled China until the end of the imperial system in 1912.

In fairness, what I’m presenting here is the version of events remembered in folklore; the real history is a lot more complicated. Many factors, scholars disagree, blah blah blah. In popular memory, though, Wu’s been immortalized as The Guy Who Opened the Gates of the Great Wall of China, and he’s never beating the allegations; his name, like that of Benedict Arnold in the United States, is a synonym for treachery. His story has all the elements of a classic betrayal: He was trusted, he was given a crucial task to perform, and at the most dramatic possible moment, he sold out his sworn loyalties for personal gain, leading to catastrophic consequences for his own side. It was almost as bad as the time Ashley Cole left Arsenal for Chelsea.

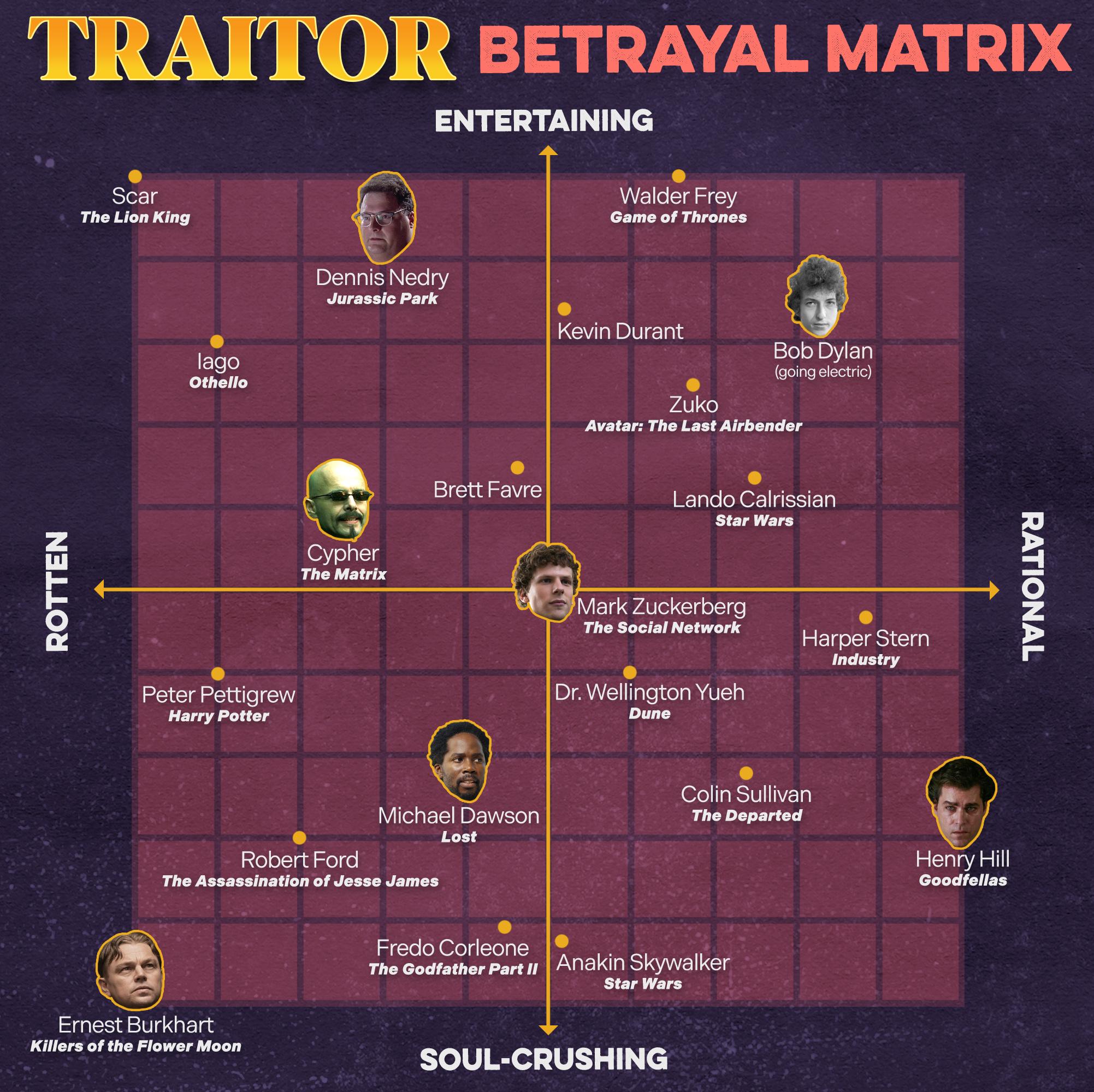

I’ve been thinking about Wu because it’s Traitors Week at The Ringer, and we’ve been debating the ins and outs of backstabbing like basketball nerds reviewing midrange jumpers. Assassins, double agents, informants, sports-rivalry jumpers, and yielders to the power of the dark side have passed under the microscope like two-loss college football teams the week before the playoff is announced. Loki ain’t played nobody! What's the essence of traitorousness, anyway? What's the most evil motive for betrayal? Does infidelity count as “treachery”? If someone you trusted were to double-cross you, would it hurt more if they did it for a payoff or if they were secretly against you all along?

Traitors aren’t great to live with, but they're often delightfully fascinating characters in stories and in history. Like venomous snakes, they’re more fun to watch when they’re behind glass. They’re fascinating, in part, because they expose the limits of our knowledge—both of other people (can you really trust anyone?) and of ourselves (can you be sure you’d never commit the same crime?). They’re case studies in the vagaries of human nature, showing us some of the possible outcomes when our commitments and our weaknesses, our concern for others and our concern for ourselves, are tested in difficult ways. Your friends are in trouble, but everyone in the airborne mining colony is counting on you to keep them free from Imperial control. Which group do you decide to protect?

In film and fiction, traitors are more compelling than most other wrongdoers—though not all traitors are wrongdoers!—because of the way they toy with the dynamics of storytelling itself. Fiction depends on connecting characters’ motives with their actions; a coherent story shows us why people do things as well as what they do. But betrayal necessarily involves concealed motives, often concealed motives with massive implications for the plot: You thought I was here to help you save the world, but I was actually here to destroy it. So betrayal can come out of nowhere, radically altering our idea of a character (Rose in Get Out, say, when we realize she’s in on her family’s evil scheme); or it can involve our knowing the truth while the other characters are clueless (Iago in Othello, who meticulously explains his plans for the audience while his victims, prisoners of dramatic irony, suspect nothing); or it can do both (Cypher in The Matrix, whose betrayal is revealed late enough to be a shock but early enough that we know before Neo and his friends do).

In all three cases, betrayal gives writers a way to complicate the rules of the game they’re playing: Instead of characters and audience all sharing the same understanding of the story, there are now multiple stories, each determined by how much of the truth a given party knows. Neo is in a story that says Cypher is his ally; Cypher is in a story that says he’s Neo’s enemy. And only one of the stories will turn out to be true.

And there are so many considerations when evaluating a betrayal! The range of possible betrayals is as wide as the range of human personalities, but some common patterns do emerge. Our Betrayal Matrix codifies some of them, and there is a further set of benchmarks I always come back to.

1. Is the treachery performed for selfishness or for principle?

Consider a double agent in the Cold War, like Kim Philby, whose spying for the Russians while employed as a high-ranking British intelligence officer helped inspire John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. A double agent might be driven by greed or by a sincere conviction that the other side is better. Which is worse: being unprincipled enough that your loyalty can be bought or being passionately committed to an evil cause? Should it trouble us at all that we see betrayal as heroic when we agree with the cause, as in the case of Andor’s Mon Mothma?

2. How close is the traitor to their victims?

It’s one thing to betray, say, a faceless corporation. It’s another to betray a friend or a loved one. One of the elements that makes Brutus’s betrayal of Julius Caesar so notorious—even though Brutus was probably acting out of principle!—is that Brutus and Caesar were pals. Anyone can stand up for the Roman Republic; not everyone would stand up for it by knifing their buddy to death on the floor of the Senate.

3. Does the traitor sleep easy, or are they haunted by remorse?

An act of betrayal hits differently when the traitor feels in their heart that what they’ve done is wrong. In Shakespeare, Richard III betrays his king, his brothers, his faction, and … well, basically everyone he meets, and—at least at first—it’s fun for him; he has no conscience to make him suffer. Macbeth, on the other hand, betrays his king and his best friend and spends the rest of the play in a sort of sweaty, paranoid, quasi-madness, unable to live with the finality of what he’s done.

4. Does the traitor get away with it, or are they punished?

Historical traitors are more likely to get off scot-free than fictional traitors, because history doesn’t care about satisfying endings. Wu Sangui, for instance, was given high rank in the Qing Dynasty and bopped along for nearly 30 more years as a rich and powerful personage under the new regime. (He then betrayed the Qing and declared himself emperor, which should have led to severe consequences, but he died before anyone got around to punishing him. No comeuppance!) Poor old Brutus, on the other hand, died by his own sword in both real life and the famous play named after the man he helped assassinate. Then, for good measure, Dante placed him in the deepest pit of hell in the Inferno. Judas arguably excepted, no one has ever failed at getting away with something more spectacularly than Brutus, the absolute GOAT of fucking around and finding out.

5. Is the traitor eventually redeemed?

The Star Wars saga loves a good betrayal-redemption arc: Lando flipping the script on the stormtroopers, Darth Vader flipping the emperor into the pit. Redemption after a betrayal can be particularly satisfying because it heals the story as well as the conflict. If the traitor’s hidden motives meant the story was no longer quite trustworthy, their redemption means everyone is who they say they are, and the narrative is reliable again. In the Song of Ice and Fire universe, by contrast, treachery is seldom redeemed because George R.R. Martin sees human nature as brutal and self-interested with few exceptions. Stories with unredeemed treachery tend to seem more sophisticated or adult; stories with redeemed treachery tend to seem more childlike. Of course there are exceptions!

But these are just a few ways of looking at traitors. There are many more, and we’ll explore some of them in the coming days. In the meantime, we invite you to pour yourself a drink, scrupulously test it for poisons, sit down someplace comfortable, make sure your back is not exposed to any knives, and join us in considering some of the greatest traitors of all time. Dear friends, why do you hesitate? Trust us! We have your best interests at heart. We would never lead you astray.