Back in January, film critics Manuela Lazic and Adam Nayman began working together on a long list that initially had more than 100 titles on it, in order to sum up something interesting—if not definitive—about the past quarter century of film. Narrowing things down was hard. They spread out their picks as evenly as they could over this 25-year period and also across a variety of styles, and for the rest of 2025, they will be dissecting one movie per month. They’re not writing to convince each other or to have an ongoing Siskel-and-Ebert-style thumb war. Instead, they’re hoping to team up and explore a group of resonant movies. We’re also hoping that you’ll read—and watch—along.

Adam Nayman: In 2019, Kate Wagner wrote an essay in The Baffler attacking the proliferation of what the author called the LPET meme—an acronym for the phrase “Let People Enjoy Things.” For Wagner, the cartoon image of two men, one forcibly sealing the other’s lips to stop him from ranting against some beloved piece of pop culture—a book or movie or show whose wide appeal implicitly placed it beyond anything but the most bad-faith, narcissistic criticism—was a symbol of a larger problem: the tendency of contemporary readers and viewers to experience any dissenting opinion on their favorite works as a personal attack and to conflate that displeasure with a commonsense refutation of any sort of analysis, period.

“It is surely a strange time to be a critic,” wrote Wagner. “As the day-to-day misery of this lucid nightmare wears people down to stumps, and the last refuge of joy and escapism is sought in mass culture, it may appear somewhat cruel to take entertainment to task. But the far worse alternative would be a world without criticism. … Until we are all forced to communicate with memes from pods wholly owned by Disney, we’re just going to have to Let People Dislike Things.”

Cut to 2025, when the invasion of the pod people—or more accurately, the empire of bots, whether they’re subsidized by Disney or Vladimir Putin or whoever—has continued unabated. Social media has been colonized by a strain of synapse-fast reactionaries, and if it can sometimes be hard to tell whether the accounts rage posting in comment sections belong to real people, the landscape mapped by Wagner has gotten only more barren. It is still a strange time to be a critic, but what’s even stranger is getting to be one in the first place. For film writers, the dystopian vibes are partially a result of gerrymandering: the culling of critical voices—whether via legacy or established publications scaling back or eliminating review sections or the shameless courting of influencers by studios who make critics jump through hoops to attend screenings or access talent.

It is, of course, still possible to dislike things and important to remember that for critics, not all dislike is created equal; opinions are less interesting than arguments, and reflexive contrarianism is just as knee-jerk as consensus acclaim. But the underlying problem—that drawing attention to the possible flaws of a hugely acclaimed or successful film is seen as a form of sedition or a miserable attempt to spoil everybody’s fun—is intractable and maddening, especially when the work in question knowingly cultivates a mixture of cool-kid hipness and rank sentimentality as a dual buttress against any sort of takedown.

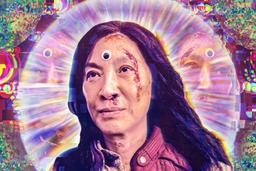

All of which is to say: I actually sort of enjoyed Daniel Scheinert and Daniel Kwan’s Everything Everywhere All at Once when I saw it in 2022, and I said so in a review for The Ringer. But I did not enjoy all of it, and I tried to argue, in print and with a few colleagues on The Big Picture, that some of the movie’s virtues—the cleverness of its setup as a combination family-drama-slash-action-movie; the speed and fluidity of its staging and editing; the apparently omnivorous cinematic appetites of its creators, with their opposite-ends-of-the-spectrum allusions to Wong Kar-wai and Ratatouille—were interlaced with its failures. Chiefly how the central multiverse conceit ends up stretching the characters, the ideas, and, especially, the ingratiating, universalist worldview dangerously thin. I thought the near-climactic image of Michelle Yeoh’s Evelyn adopting an unorthodox fighting stance while staring down her angsty (and apocalyptically all-powerful) daughter made for a telling emblem of EEAAO’s earnest, overbearing, enervating approach: “Watching it,” I wrote, “is like being brutalized by good vibes, or trying to get a breath in edgewise while a pair of ambitious, well-intentioned filmmakers try to hug you to death.”

A few days after I posted that review—and long before Everything Everywhere All at Once hit its stride as an unlikely but retrospectively inevitable awards-season darling—I got an email from a stranger with the subject line “you asshole.” Figuring it could be in reference to anything, I read on. The gist of it was that by not giving a rave to EEAAO, I was exposing myself as a miserable fraud with a destructive agenda—the same sentiment distilled in the extremely popular and well-circulated review of the film by Letterboxd user CosmonautMarkie, who wrote, “Watch it and have fun before film Twitter tells you it’s overrated.”

Now, I’m not sure that Everything Everywhere All at Once is “overrated,” exactly. If we want to use the Academy Awards as a bellwether of quality—I know, but just go with me on this one—it’s certainly no worse than the two Best Picture winners preceding it (Nomadland and CODA) and considerably better than either Green Book or The Shape of Water. Guillermo del Toro’s fans don’t like their idol being chided, either; Frankenstein is one of this year’s exemplary LPET causes, the other being One Battle After Another, whose supporters have been excessively defensive against valid critiques of the film’s revolutionary ardor and racial politics. If anything, I’d say that Everything Everywhere All at Once was a very deserving Best Picture winner, with the caveat being that “deserving” in this case is also a bit of a put-down—an indication that by making good on its title and mashing together so many apparently incompatible genres, visual styles, and tropes, the Daniels succeeded in playing all sides against the middle(brow). There’s something skillful in the way Everything Everywhere All at Once leverages familiarity against originality and puts across the idea that Evelyn and the other members of her family contain multitudes; formally speaking, the Daniels do a better impression of Edgar Wright than the man himself has managed in some time. But I also don’t much like being hugged to death, and the warmer and fuzzier the movie gets, the more it loses its rhythm, momentum, and nerve—and I get the feeling that this decline isn’t evidence of a misstep or a wrong turn but is exactly the trajectory its makers had in mind all along. Manuela, did you enjoy Everything Everywhere All at Once? If so, does it bother you that I didn’t? Or alternatively, does it bother you that so many other people do?

Manuela Lazic: At the risk of coming across as a contrarian, since I already wrote rather negatively about the similarly wildly popular Uncut Gems last month, I must admit that I didn’t enjoy Everything Everywhere All at Once, either. I’m glad you agree, and I’m not alone in this. But I also can’t say that it bothers me if other people like it; it’s a free country (supposedly). Yet I can’t seem to stop my eyes from rolling up in their sockets, much unlike googly eyes. As you explained, this film packs in so many references and genres, and when I see how beloved it is, I wonder what all its fans would say if they saw the bits in their original context—if they didn’t watch everything all at once. Of course, many EEAAO spectators have probably seen In the Mood for Love, for instance, and perhaps they enjoy being reminded of its visual style. But those green-tinted scenes between Michelle Yeoh and a dapper Ke Huy Quan in an alley don’t come close to the deep melancholy of Wong Kar-wai’s film and its ability to communicate so much with so little dialogue. These references are little more than shortcuts to other, better films whose greatness is all their own. The Daniels’ film isn’t so much a celebration of In the Mood for Love and the other films it references as it is a bastardization of them—a maceration to try to extract some coolness and artistic currency out of them.

Despite the zeitgeist—or, rather, because of it—I didn’t see EEAAO when it came out. I had seen the manic trailer for it at a theater, waiting for some other movie to start, and feared I’d suffered an aneurysm and swore to keep away: It was too much noise for me. When I watched the film for this discussion, I was therefore quite surprised by the sluggishness of its rhythm and plot. I’d expected something much tighter, more quickly paced, and more coherent, à la Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse; instead, the jumping around between universes feels chaotic, but not in a good, fruitful way. The very concept of teleportation being triggered by doing something absurd feels like a narrative cop-out: Anything goes, as long as it’s wacky, which is irritating in and of itself. I enjoy absurd comedy, but here, it serves only to dodge structural questions and drive the narrative forward and sideways and, as you said, to serve a terribly sentimental and childish idea: If everything is absurd, why not jump into the void? Just as its cinematic references are shallow, EEAAO’s existentialism is puerile and facile. It’s interesting how The Tree of Life could convince me that love is the answer, but EEAAO couldn’t.

Perhaps that has to do with how Manichaean its vision of the world is. Alpha Waymond, the version of Evelyn’s husband from the dimension that knows about the multiverse, tells her point-blank that her life is a total failure because she wasn’t able to make just one of her dreams come true. In the ITMFL dimension, Evelyn is a successful actress and martial artist because she turned down Waymond way back when, yet her salvation comes when she reconnects with him (not at all the idea in WKW’s film, but whatever). There is no real “what if” since all roads lead to Waymond. The Daniels put personal potential and happiness in opposition and ultimately send Evelyn back to her launderette, her taxes, and her husband. At one point before this sappy conclusion, Evelyn is seduced into giving in to the absurdity of life by her daughter, Joy (Stephanie Hsu), or rather by Jobu Tupaki, her evil, alienated version. She rejects everything and everyone and delights in her abandon, and for a brief moment, I thought that the film might go in an interesting, genuinely subversive direction, where the very idea of “potential” would be challenged and give way to self-determination and freedom. But the Daniels didn’t see it that way, and they instead portray Evelyn’s rebellion as a nihilistic, destructive turn. In fairness, this simplistic perspective of good and bad echoes that of Joy/Jobu Tupaki, a clearly depressed young adult who doesn’t yet have a sophisticated understanding of the world, but it is striking how the film doesn’t manage to address Joy’s concerns with anything more convincing than sentimental platitudes about family bonds and enjoying the little things.

Many lauded the film’s flamboyant visual language, its explosion of colors and vivacity, but much like you felt hugged to death, I felt like Alex in A Clockwork Orange, bombarded with so many stimuli that I would soon lose my sense of self. The higher frame rate, when not used to then slow down the action, makes for an uncanny feeling, where people move a little too fast. Jobu Tupaki’s ever-changing colorful outfits are like skins in Minecraft, fun but temporary and meaningless. This detachment from the tangible world matches the film’s emotional remove: Everything is a shortcut meant to make the spectator feel seen; each of Evelyn and Joy’s conversations is set to trigger an intellectual recognition rather than an emotional one.

All right, I’ll say it: EEAAO feels like 139 minutes of doomscrolling. Would you agree? Or am I being too nihilistic myself?

Nayman: The doomscrolling analogy is a good one, even if I prefer your invocation of poor trussed-up Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange. I wonder whether being force-fed a steady media diet of epic bacon would make me nauseated or destroy my taste buds entirely. It’s also funny to imagine a Clockwork Orange–themed parallel reality in Everything Everywhere All at Once, a reversal of the jaw-dropping image in Space Jam: A New Legacy—another multiverse-of-madness movie—Alex and the Droogs mugging alongside hundreds of other Warner Bros.–trademarked characters. Or maybe Evelyn and Waymond could have wandered into the photorealistic re-creation of the Overlook Hotel from Ready Player One. I still maintain that Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of Ernest Cline’s dystopian bestseller was only deceptively reverent and that the film’s razing and renovation of various intellectual properties were being undertaken at least semi-satirically. On the other hand, Spielberg himself hailed the Daniels for what he called “amazing genius work,” which suggests that somebody here—either the most gifted American commercial filmmaker of all time or the two of us—needs to snap back to reality.

Spielberg’s appreciation for the Daniels is rooted in a recognition that what they’re attempting in their work is not just hard to pull off technically but also easy to dismiss as mere freneticism that pauses only to flatter-slash-flatten the audience’s frame of reference (although I bet he liked the Jurassic Park bit in Swiss Army Man). The fact is that a significant percentage of the past 50-plus years of mainstream American cinema has been made, consciously and often disastrously, in Spielberg’s movie brat image. The only other contender in terms of influence, impact, and industrial shlep is Quentin Tarantino, a Gen X Spielberg to the point that his “mature” films play almost as spiritual remakes (Inglourious Basterds and Schindler’s List; Django Unchained and The Color Purple; Hateful Eight and Lincoln).

The story goes that QT visited Yeoh in Hong Kong in 1996 while she was recovering from injuries incurred on the set of The Stunt Woman, and he rekindled her fading love for filmmaking in the bargain. “The next thing I knew, we were talking and I was coming back to life,” Yeoh told The AV Club. “I’ll never forget it. It was like, ‘I do love what I do.’ And that was a turning point where I felt, ‘I’ve paid my dues.’” One of the reasons that I’m hesitant to fully write off EEAAO is that it really does play like a proverbial love letter to Yeoh, whose performances in Hong Kong action classics like Yes, Madam, and The Heroic Trio hover in rarefied air. The Daniels’ obvious affection for their star—rooted in the same video store– and DVD-driven cinephilia as Tarantino’s—resonates beyond the rest of their shtick. You’re right about how ultimately the movie reduces down to platitudes about family life, which is why—deep breath—it’s possible to see it as the Daniels’ Kill Bill, which justified all of its hard-R-rated violence (and most of its gratuitous excesses) by revealing itself in the end as a fable of maternal protectiveness. But Tarantino was also clever enough—as usual—to leverage his girl-power iconography against a withering patriarchal critique, with David Carradine’s control-freaky comic-book fetishist Bill as an obvious auteur stand-in. The Daniels aren’t far enough into their careers yet for the kind of coded self-reckonings that Spielberg and Tarantino have attempted on the other side of middle age, which might be why EEAAO’s coda feels not only forced and predictable but also artificial. It’s an earnest but callow simulacrum of domestic bliss, of laundry and taxes, and while the Daniels are smart enough to fleetingly suggest that this ending could just be one more pastiche among many, they’re so determined to make the viewer happy that they tamp down any true sense of ambiguity. Evelyn and her family deserve this, they say, and so do you. Let People Enjoy Things.

I’d also concede ground to the charm of a lot of Quan’s performance, even if he’s been on an almost historically bad run of projects ever since. At the other end of the spectrum, the participation of Anthony and Joe Russo—the callow project managers currently incinerating audience standards one expensive tire fire at a time—suggests something more malignant: While the brothers didn’t receive Oscars due to Academy rules that only three producers can be honored per Best Picture winner, their fingerprints are all over the film and its success. By default the Daniels have more wit and imagination than the Russos, yet their collaboration makes sense. Beneath those wacky, absurdist surfaces—the WTF moments made mandatory by the script as a way of moving laterally between realities—EEAAO represents solid, quality-controlled, vaguely Marvelized product; I seem to recall from earlier this year that both Thunderbolts* and Fantastic Four: First Steps concluded with intergenerational group hugs as well. I also remember the worst part of the latter being the apparently Russo-directed stinger, featuring a hooded, as yet faceless Robert Downey Jr. (it takes a lot to ruin Doctor Doom, the best comic-book villain ever, but I have faith). My point is that while EEAAO surely contains multitudes, there’s some pretty dubious DNA in there. Not to mention the fact that there’s been a recent proliferation of mutant offspring: Whatever the individual intentions of their creators, movies like The Life of Chuck, A Big Bold Beautiful Journey, and Rental Family have been packaged and promoted under the sign of EEAAO-core. Do you see the movie’s influence around the edges of certain new releases like I do? And whatever you might think of the movie’s quality, is it going to hold up? Or will we eventually come to see it as the cinematic equivalent of a stale everything bagel?

Lazic: Perhaps I just don’t really buy into the multiverse idea and I find the question of alternate life stories to be a dead end most of the time. As we say in French, avec des “si,” on mettrait Paris en bouteille, meaning, “with ‘what ifs,’ you could put Paris in a bottle.” Considering all the possibilities leads nowhere because it can lead anywhere. Still, some filmmakers have managed to use the concept intelligently, more as a tool to address something else than as a gimmick: Krzysztof Kieślowski’s wonderful 1981 film Blind Chance imagines the different personal and political consequences of a seemingly innocuous event on a young man’s life, thus exploring the fragility of one’s convictions; in his masterpiece Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, penned by the ever-melancholic Charlie Kaufman, Michel Gondry bent the rules of time and space to deconstruct romantic regret.

The Daniels keep their takes on the multiverse and alternate timelines pretty simple and end up with a much less interesting movie: All the same people are present in all the dimensions, and they all have versions of the same relationships. Although the idea of multiple realities should complicate and enrich a story, here, again, it feels like a lazy shortcut, a way to get your actors to wear different outfits and pretend to say something deep about choosing love. What bothers me most about EEAAO is precisely this: It masquerades as ambitious. Kieślowski making an alternate-reality film where catching a train (or not) determines whether someone will join the Communist party and/or find happiness is bold (so much so that the film was banned by Polish authorities until 1987). Gondry and Kaufman playing with memory and fate to ask whether love and pain are inevitable is audacious. EEAAO is all smoke and broken mirrors.

Andrew Gruttadaro (Manuela and Adam’s editor): I just want everyone to know that Manuela originally ended her last missive by being nice and ceding some ground to EEAAO and the Daniels, Yeoh, and Quan. And I, like a real curmudgeon, said, “Nuh-uh, no truces here. Neither Everything Everywhere All at Once nor its fanatical horde needs a bone thrown their way.”

But I have a reason for giving this note besides just being mean: As Manuela’s and Adam’s theses—and their mere existence in juxtaposition with this movie’s larger reception—prove, the legacy of Everything Everywhere All at Once will always be epitomized by this standoff between staunch critics and the fans who take such analysis as an affront and by what the clash says about the state of film criticism as a whole. Clearly, Manuela’s and Adam’s stances on EEAAO haven’t been softened by the passage of time, and I imagine that many people will read their back-and-forth pan with their middle fingers pointed at their computer screens. I’m not here to make a final judgment on which camp is right (although you can probably guess which camp I belong to), only to pinpoint what seems to be the larger story when it comes to this movie. In this timeline, at least, it feels like this giant chasm will always define EEAAO. There’s something deeply funny—and fitting—about that.