When he’s not “waking the dead” from his farmhouse and studio headquarters in Walpole, New Hampshire, or his condo in Brooklyn, Ken Burns is often screening films across the nation that for 44 years has been his muse. Burns and I spoke in early November, after he had just returned from barnstorming through old Revolutionary War battlegrounds and historical sites, small-town cinemas and local theaters. He and his production team were gearing up for the release of their new film, The American Revolution—a six-part, 12-hour documentary that debuted Sunday on PBS and will air through the end of the week.

Burns’s 38th full-length release, The American Revolution is both an overt reckoning with founding-era mythmaking and an attempt to mine an authentic, shared American origin story. It arrives at a perilous moment for scrupulous historical efforts in media. Burns, who turned 72 in July, told me that in the decade he spent working on the film, his primary concern was not letting the context of the present shape his work. “You want to make a film that lasts the ages,” Burns said over the phone. “The last thing you want to do is play to the present.”

In September, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting—responsible for channeling around half a billion dollars in congressionally approved funds to Burns’s longtime production partner, PBS—eliminated the majority of its staff because President Donald Trump championed and signed a bill into law that called for more than $1 billion in public media clawbacks. A month earlier, in anticipation of the pending legislation, PBS had announced that it was slashing its budget by 21 percent. In the spring, Burns himself was caught up in federal censorship fervor: After he screened The American Revolution at West Point to a favorable reception, the organizers behind a similar event at the U.S. Naval Academy backed out over concerns that the director’s past criticisms of Trump might engender backlash from the right.

Burns’s work has long provoked a wide spectrum of responses. For decades, he’s fixed his creative eye on our nation’s foundational cleavages and commonalities: race, westward expansion, militarism, baseball, jazz. He’s been knocked for being both too liberal and too saccharine, too harsh and too tame. Burns is a registered Democrat, but his work tends to occupy the so-called vanishing middle. “I’ll have to lie low,” he told The New Yorker before the release of his acclaimed 10-part Vietnam War documentary in 2017. “A lot of people will think I’m a Commie pinko, and a lot of people will think I’m a right-wing nutcase, and that’s sort of the way it goes.”

Sarah Botstein and Ken Burns at George Washington’s Mount Vernon

He is, unquestionably, the premier documentarian of our age, the only figure in thrall to the medium who has shown the ability to consistently attract audiences in the tens of millions for meticulous, multi-hour historical epics. The new film, which he codirected with longtime collaborators Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt, at once fits within and expands this footprint. Functionally, The American Revolution relies on reenactment more than any of Burns’s previous works, but it does so by decentering the visual performers—never focusing on their faces, filming them at a distance or slightly out of view. These vignettes are elevated by an expansive voice cast interspersed with Academy Award winners, historians, and scholars from across the world. The film contains no archival footage and only a single still photograph. Burns framed these confines as both a challenge and an opportunity.

“It’s been, I think, the biggest anxiety and the biggest resistance to tackling the revolution,” he said. “I’d done a two-part film in the ’90s on Jefferson, but we had portraits of him. And anytime you show Monticello, you can talk about him. I did just a few years ago a two-part biography of Benjamin Franklin, and there are lots of portraits of him. But here, we were introducing scores of characters that don’t have portraits. Ninety-nine percent of the population didn’t have their portrait painted. So they have to come alive.”

His patented zoom effect appears throughout the documentary but is used on paintings and portraits rather than monochromatic live images. To help render the defining battles of the conflict, the film relies on animated maps and contemporary footage on-site. If there’s a main character in The American Revolution, it’s the land itself, the prize Burns and team posit was at the core of the bloody international dispute. The film is dogged in its commitment to reorienting our understanding of the war for American independence, that it was, and still is, a dynamic, imperfect process.

I wanted to start by talking about the emphasis the film places on the racial and ethnic variety within the 13 colonies and their relationship to both Native nations and enslaved laborers. I think it’s the most daring aspect of the film, at least thematically, and also the one most liable to ruffle some feathers.

Can I change the word “emphasis”?

Sure.

We’re umpires calling balls and strikes. “Emphasis” implies that we’re superimposing a particular lens through which we’re going to see the revolution and judge the revolution, but we’re not. In the highlight reel of life, Babe Ruth always hits a home run, but we know he struck out more times than he hit a home run.

Heroism isn’t perfection. You don’t have to just lament, “Oh, we have no more heroes because this person wasn’t 100 percent perfect.” We missed the whole point of it.Ken Burns

We wanted to tell and spend a decade—almost a decade—trying to tell a complex, more accurate picture of the revolution. And that will necessarily entail women, enslaved and free Black Americans, Native people who are assimilated and coexisting, and those Native nations that are as distinct [from the colonies] as France is from Prussia. Who’ve been players on a world-trading scene and diplomatic scene for centuries. We just go and try to tell the story that we know took place.

You beat me to my next question. I was going to ask how you think about that work. Because, whatever the intention, it discombobulates many conceptions of who was involved in the American Revolution and the issues at the core of the dispute.

The sort of shortcut is to adopt a fashion of historiography and then superimpose that over stuff. And we just don’t believe in that. I have this neon sign in my editing room in lowercase cursive. It’s been there for years, and it says, “It’s complicated.” Every filmmaker, when a scene is working, you don’t want to change it. But we’re always changing it. And I’m insisting on changing it, [particularly] when you learn destabilizing and contradictory information.

I remember one time in our Jazz series, Wynton Marsalis said, “Sometimes a thing and the opposite of a thing are true at the same time.” We operate under that principle. The most important person to the creation of our country is George Washington. He is also very complicated, deeply flawed. He’s rash on the battlefield, risking his life and therefore the whole cause, and makes at least two gigantic tactical errors that lose two major battles of the revolution. But we don’t have a country without him.

And if you can’t handle that—I don’t mean you—but if one can’t handle that, then you don’t know what stories are. You can’t watch Yellowstone, say, supposedly the darling of the right. You can’t see a Shakespearean play. You can’t watch Succession. You can’t watch anything dramatic or anything historical because it’s going to always have that stuff. Lincoln was talking about colonizing Black people back to Africa or to South America.

Right. Liberia and the failed Linconia settlement in Panama.

Exactly. And doing so as late as April of 1861, when the guns were still going. And yet, who’s our greatest president after George Washington creates the country? Abraham Lincoln.

There are a couple ways of thinking about what it feels like we’re circling around. One, which is at the forefront of our national politics, is that any examination of our past that disparages the established heroes of the American narrative is inherently faulty, dangerous, invalid. But to my mind, there’s another equally salient line of thinking. And it's that, when we take a holistic view of these flawed, human figures, folks tend to have both a more enriching connection to them and find a trove of other individuals with whom they can identify.

Heroism isn’t perfection. You don’t have to just lament, “Oh, we have no more heroes because this person wasn’t 100 percent perfect.” We missed the whole point of it. It’s that we learn something about the human condition and what we may do.

I hope that the film raises questions. What would I have done? Would I have been willing to fight for a cause? Would I have been willing to die for a cause? Would I be willing to kill somebody for a cause? Would I have tried to keep my head down? What causes James Horton, the 9-year-old free Black kid who hears the first reading of the Declaration [of Independence] in Philadelphia and doesn’t for a moment think it doesn’t apply to him? He knows it applies to him.

Every film we made rhymes with the present because human nature doesn’t change.Burns

Especially in the early episodes, I was struck by the degree to which many, many people just want to get free by whatever means possible—including joining the British. And those dilemmas and decisions go far beyond just Black Americans.

You hit the nail on the head. Everybody is unique. Everybody’s wondering, what is the best thing for me to do? Am I going to be a loyalist? Where’s my best chance for freedom? This slavery business sucks. And maybe where I am in Virginia, the best thing is to go with the British. Maybe where I am in Philadelphia, the best thing is to fight for the patriots.

Everybody has agency. That’s a whole idea underpinning the American project: that we have agency, that each person has that right. And so, as the scholar Jane Kamensky says, "The liberty talk is leaky.” The people who are hearing it, who are serving, who are working, want it as much, if not more, than the people who are complaining that what the Brits are doing is akin to slavery.

How much, if ever—especially in this moment—do you consider the pushback that a commitment to the kind of historical nuance we’ve been going back and forth about can engender? Particularly living what you just lived through with PBS, seeing these executive orders about “patriotic history” and everything else?

You’re not going to believe it, but none.

You don’t think about it at all?

No. What we do think about—and we have to discipline ourselves almost like Odysseus tied to the mast, resisting Circe and the siren call—is how much it rhymes with the present. We get it. Every film we made rhymes with the present because human nature doesn’t change. Today’s a school day. I have a couple dozen films probably being shown today. Civil War, maybe. Hundreds of times in classrooms. Not the whole thing, but maybe 40 minutes on Abraham Lincoln or 40 minutes on the Battle of Gettysburg or 40 minutes on Black troops. Whatever it is, they’re being looked at all across the country. You don’t get a durability like that if you’ve spent your time saying, “Isn’t this so much like today?”

I used to say about a film that came out in 2011, “What if I told you I’ve been working for years about a film about a single-issue political campaign that metastasizes with horrible, unintended consequences? About the demonization of recent immigrant groups to the United States, about smear campaigns during a presidential election and anxieties by a group of people that they’d lost control of their country and wanted to take it back?” You would say, “2011, Ken: this is the Tea Party. This is what’s going on.” But this is the story of Prohibition.

Those rhymes always happen. And because this took 10 years, there were rhymes in 2015 and 2016 that don’t exist anymore. There are rhymes now that are louder than they were in 2015 or 2016, but I can’t pay them no mind. Then your next question is going to be about the political dynamic.

How’d you know?

The thing is that art is here to offset. A political dynamic is superficial. It’s binary. And there are no binaries in nature. If you believe in that white hat, black hat kind of thing, then you’ve got to cancel George Washington. But then you have to cancel everybody else, and no one’s left.

The Greeks used the gods as an example to tell about a negotiation within a person between their strengths and weaknesses. Washington knew slavery was wrong. Jefferson knew slavery was wrong. And as the historian Annette Gordon-Reed says about Jefferson, “How could you continue to do something if you knew it was wrong?” And then she says, “Well, that’s the human story for all of us.” She’s not letting Jefferson off the hook. She’s putting the rest on the hook for our own failings.

Take me through the challenge of bringing this all to life without any archival footage.

It became not a liability, but an opportunity. Making a film is a million problems. But I don’t see the word “problem” as pejorative. It’s just inevitable friction. So the inevitable friction of this project was that there are no photographs or newsreels. So what do you do? I get over my aversion to reenactments, and we do it differently.

Instead of filming somebody reenacting a battle, we spend years and years filming dozens of reenactment groups—from French to Native American to British to militia to Continental Black, whatever troops they are. One of my favorite shots is just a Black hand holding a musket in a Continental uniform. That one shot instantly is signaling something about this story. To shoot these impressionistically, not looking at faces, but to see hands, see details, see boots in the mud, see aerial stuff from drones, you just get a sense of what it was like.

Instead of reenacting, we collect a critical mass of footage to complement our paintings, our drawings, our maps, our documents, the signatures, the gravestones, the other live cinematography of the land itself, and mix it in with commentary. And not just the voices of the top-down people. We have 400 first-person voices in this film, and most of them are spoken by people I had never heard of, and I presume you had never heard of, either. Plus, I think I have to say, the greatest cast that’s ever been assembled for any movie or television show.

Art is here to offset. A political dynamic is superficial. It’s binary. And there are no binaries in nature.Burns

Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep and Josh Brolin and Samuel L. Jackson …

And Morgan Freeman and Laura Linney and Claire Danes and Damian Lewis. I’ve named, maybe, a tenth of the voices, and each one of them just can bring it alive. All of that overcomes whatever the particular recalibrations necessary were. We began to rejoice in the fact we have no photographs.

How do you land on who to approach? Give me your pitch to Hanks.

Well, there’s a lot of people that I’ve worked with before. Tom, for almost 25 years. Morgan, for more than 35 years. Sam for that long as well, Meryl maybe 15. And so there’s a lot of people that we use all the time. Just folks: They’re not celebrities. I always just get so pissed off when people say celebrities because I’m not asking Kim Kardashian.

They’re actors.

I'm asking the greatest actors in the world to do it. People who lose themselves in the portrayals. We do this over a 10-year period, so you can just say, “We’ll do it when you’re ready.” It’s very rare that someone turns us down. And most everybody is so wonderful and generous.

I remember in the mid-aughts, Tom had read some voices that we had collected for him of a newspaper editor in Luverne, Minnesota—one of the four towns that we were telling the entire story of World War II through. And he wrote me a letter saying, “I'm dreaming of Al McIntosh …”—that was the editor’s name—“... is there more?" And we went and found more and turned Al McIntosh into literally the Greek chorus of the film.

Jeffrey Goldberg, Sarah Botstein, Ken Burns, Annette Gordon-Reed, and Tom Hanks during the New York premiere of ‘The American Revolution’

One of the things this film made me think about again and again is the idea of a shared American past. To you, is a shared past everyone moving in the same direction? Or is it everyone brushing shoulders?

Everybody’s involved. I remember looking at this film last September [before the election], and I thought, Geez, there’s lots of places where folks are going to find a connection to this film. And I started first worrying about it, and then I said, Wait a second. That’s what I want. Everybody’s got a connection. This is our origin story.

I began this project when Barack Obama had 13 months to go in his presidency. There’s been a lot of water under the American bridge. And people like to say that history repeats itself. It never does. My favorite thing is something that Mark Twain is supposed to have said. “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” Because every film I’ve made, it’s like rhyming in the present. And this one perhaps even more because of the supposedly fraught moment that we’re in right now.

Another really compelling thread in the film—and one that may end up throwing folks’ understanding of the American Revolution for a loop—is the degree to which the war is revealed to be a dispute over land and westward and southern expansion. Was the question of how, exactly, to show that a running dialogue behind the scenes?

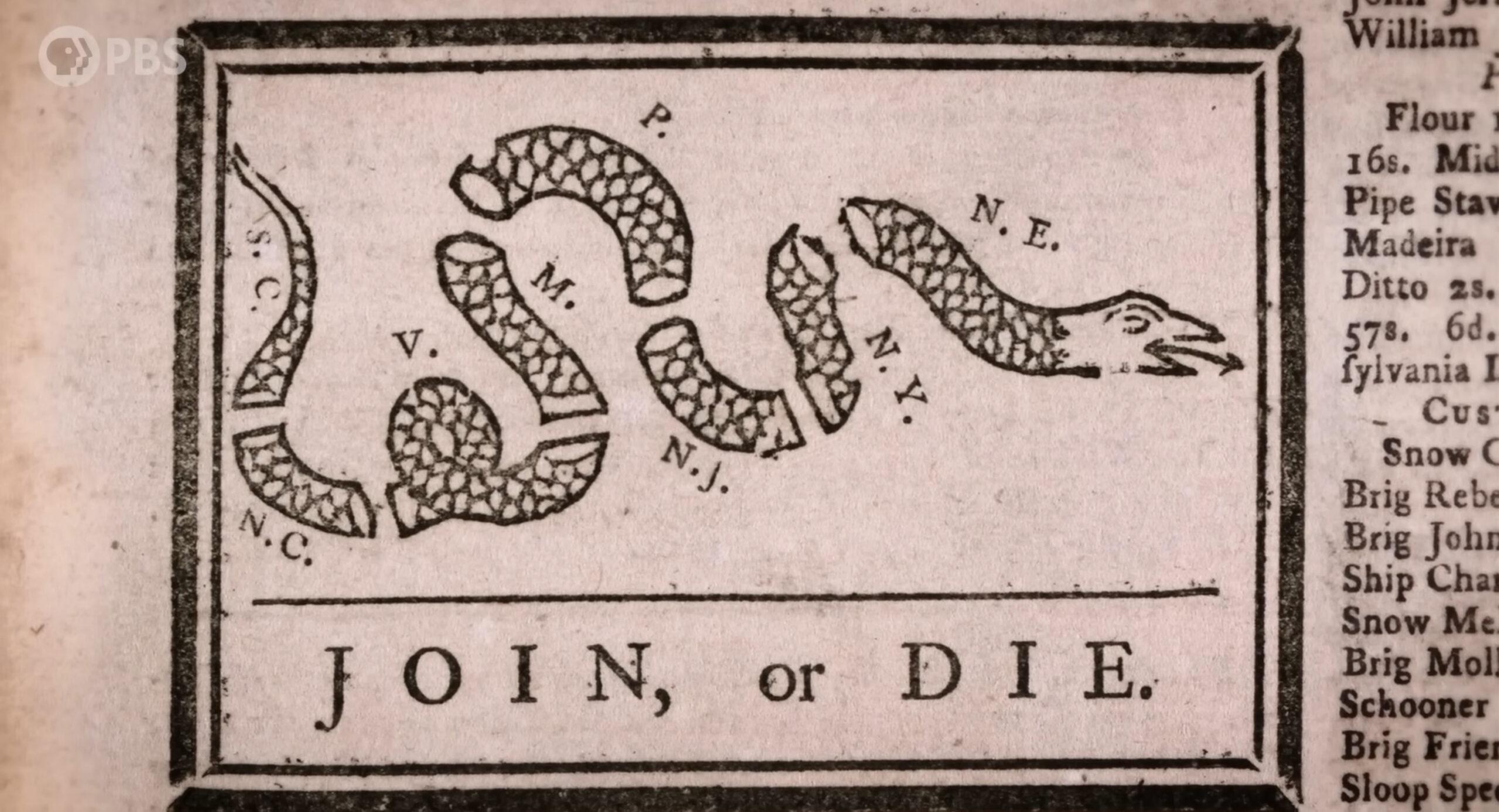

Yeah. I chose to center the Native American land moment at the very beginning of the film. I changed the opening sentence of the formal introduction after that prologue about Benjamin Franklin being inspired by the Iroquois Confederacy and trying to attempt the same thing. We had that, “This was not just a struggle between British citizens over taxes and representation.” And I added, “Indian land taxes and representation.”

Because of course it’s about land. This global war is the fourth war over the prize of North America. And what represents that prize? It’s that land. But the land has also been inhabited for, you pick the number, 12,000 to 22,000 years, by other people who do not have the same tradition of landownership. They’re not disinterested in the land. As we openly [quote in the first episode], “White people don’t think we know how valuable the land is. We know how valuable it is.” This is the open door to just say, “Well, they’re really savages, and they don’t really care about it.”

Everybody’s present moment is always the worst. And clearly, the revolution shows, it was much more divided then than it is right now.Burns

“We might as well take it.”

Someone points out in the film they didn’t call this the Eastern Seaboard Congress. They didn’t put George Washington in charge of the Eastern Seaboard Army. They called it the Continental Army, the Continental Congress. They knew what direction they were headed.

The Brits get a “be careful what you wish for” [moment] when they win what we call the French and Indian War and everyone else calls the Seven Years’ War. Their treasury is bankrupt, they’ve got the most far-flung empire on the earth, and they can’t protect people. So they say, “You can’t cross the Appalachians.”

The colonies are going, “What? That was our whole plan.” The new immigrants are going, “What? We were going to own land for the first time in 1,000 years.” And it’s enraging the mega-speculators like Franklin and Washington, who’ve bought up tens of thousands of lands to sell to those colonists. So this is a big deal. Land’s a big deal. You can still get an A on the test if you say, “Taxes and representation.” But it’s more complicated.

The thought that democracy wasn’t really an intention of the dispute but a by-product of it, some folks would call that a very radical contention.

Yeah, but it’s organic and it’s true. And it then becomes, to me, weirdly inspirational. John Adams does not intend to extend this to anybody that isn’t a white male who has property. And yet, if you’re going to win this war—he doesn’t fire a gun. George Washington does. Thomas Jefferson doesn’t. But Alexander Hamilton does, Aaron Burr does, James Madison does.

The people who are going to win it are the teenagers and the ne’er-do-wells and the felons and the recent immigrants without any property and the second and third sons without a chance of an inheritance. They’re going to win the war for Washington, and they have to be accommodated. And so what you find is that this elite aristocracy that will run things has got to also acknowledge that there is a bottom-up story of the people who did the fighting and the dying.

When your World War II documentary, The War, came out back in 2007, you talked about your desire to “unwrap it from this bloodless, gallant myth” that the narrative of the conflict had been bogged down in.

The Good War.

Exactly. I wonder, did you feel a similar impulse with this film?

Oh, totally. Even more so. Because of the fact that there are no photographs or newsreels. We know how bad World War II is. We’ve seen the consequences of the Holocaust. We’ve seen the bodies, the cities in rubble. But all we got here are some paintings, and they’re pretty romanticized. Because we’ve got such big ideas coming out of this conflict, we’ve had an unarticulated conspiracy to just say, “OK, let’s not diminish the big ideas in Philadelphia by reminding people that this was an incredibly bloody war.” I think the opposite is true. By understanding it as just a ghastly revolution—dying by bayonet or musket or cannon is terrible—those big ideas are not diminished. They’re actually made more inspirational.

Particularly today, everybody’s present moment is always the worst. And clearly, the revolution shows, it was much more divided then than it is right now. Maybe going back to that origin story and accepting all of the things that you’ve brought up, that democracy is a consequence, not an intention, of it, that there are a wide variety of people involved, gives [another perspective].

I’d like to put you through a little quiz. I want you to give me your five favorite living filmmakers, but they cannot be people you’ve worked with. All right?

Oh, Jesus. That’s impossible. OK, I love Werner Herzog. We’re friends, but we’ve never worked together. Does that count?

Yeah, that counts. I’ll allow it.

I love Michael Mann. I love Martin Scorsese. Francis Ford Coppola. They don’t have to be Americans, right?

They can be anybody.

Cristian Mungiu, who did 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days in 2007, about abortion. One of the great films of the last few decades. The Lives of Others by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. I go every year to the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado, and I just mainline 15 to 20 movies in a three-and-a-half-day span. None—save if I’m premiering a film of my own—are mine. There are other people’s documentaries and mostly feature films and mostly from another country.

God, this is an impossible thing. You can’t do that to me. I can give you a list of dead filmmakers. A lot easier: Luis Buñuel and Akira Kurosawa and Orson Welles come to mind.

You’ve said in the past, “When you’re doing an epic poem, you can’t be an encyclopedia or a textbook.” Do you still think about your work like this?

I think the biggest thing is to understand that the making of a film is not an additive thing, but a subtractive thing. There are 12 hours. You are constructing a narrative, but at the same time, the way it’s constructed is by subtracting all the material that you’ve collected. So if it’s 12 hours, we’ve got 50 times that in material, and the original version of it was 24 or 30 hours. You’re constantly whittling down and taking away.

The analogy that I use a lot is that I live in New Hampshire and have for the last 46 years. We make maple syrup there. It takes 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup. You don’t boil it. If you do that, you get rock candy. You evaporate it off just under boiling temperature, and you get this elixir.

The biggest thing is to understand that the making of a film is not an additive thing, but a subtractive thing.Burns

Now that the dust has settled a bit, how are you feeling about the future of PBS?

Well, I think the future of PBS is not in doubt. It will continue. The problem is that the killing of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting will affect my budget significantly. It’s at least 20 percent of every budget, sometimes more. It’s caused PBS to lay off 100 people. But the biggest thing is that the Corporation for Public Broadcasting supported sometimes much more than 20 percent—sometimes 50 percent, sometimes 75 percent—of its 338 individual member stations all across the country. And so those stations that are dependent on CPB money will either fold or have to do some kind of magic trick.

There are going to be people who are coming up, who don’t have the track record that I do or the contacts, that I could say, “Hey, look, you got to help. You got to dig deeper because we need you to do this next thing.” Where are they going to come [from]? And there are many other places that were affected where people had a chance to really cut their teeth as they’re coming up and then make a significant mark with films that are honorably produced and adhering to the highest journalistic and scholarly standards. Where are they going to go?

Last one. Is this the most important film you’ve ever made?

Here’s how I phrase it: [My films] are my children. And since these films are for PBS, I can take 10 years in this case—over 10 years to do Vietnam, almost eight years to do The War, and 10 years to do National Parks. I get to deliver a director’s cut. What I’ve said about this and one other film, The U.S. and the Holocaust a few years ago, was “I won’t work on a more important film.”

I'll stand by that. I know that many films that I’ve done—like The Civil War, maybe Jazz, maybe The War—are as important. And I hope to continue to be working on projects. But I know how important this story is: Understanding this story helps us. Having a real past, particularly about our origin, ensures that we have a richer and more dimensional understanding of our present. And, therefore, we may have the ability to deliver ourselves a better future, one that I think most people don’t feel right now.

History is the best teacher, and being armed with good history gives you a spectacular advantage and the ability not to just buy into our contemporary binaries, the one and the zero of the computer world, the yes and no of the political world, the good or bad of our false morality. It’s really complicated. And I think when people understand that, then in their own lives and with the people that they love, they tolerate contradictions and undertow.

The novelist Richard Powers said, “The best arguments in the world won’t change anyone’s point of view. The only thing that can do that is a good story.” And I think a good story, it’s still not trying to convince you. It’s just saying, “This is.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.