Life in the NBA comes at you extraordinarily fast. Two seasons ago, the Boston Celtics won their 18th title and seemed set to go on a dynastic run. Eleven months later, they were upset by the New York Knicks in Round 2 of the playoffs and watched Jayson Tatum, their 27-year-old, four-time first-team All-NBA superstar, rupture his Achilles tendon. Today, Neemias Queta is Boston’s second- or third-most important player, while Josh Minott was recently demoted out of the starting lineup and replaced by Jordan Walsh.

In other words, the dam has been breached.

Jrue Holiday, Kristaps Porzingis, Al Horford, and Luke Kornet are not walking through that door. That’s $170.7 million worth of talent crossed with an invaluable dose of championship experience. Left in their wake is a crater that’s filled by a mix of familiar faces, rookies, and cast-offs. Half the roster is in a role they either aren’t ready for or are incapable of occupying on a team that aspires to be anything more than a plucky out. We already knew that this was a gap year—a reality that makes on-court analysis pale in comparison with the big-picture questions about relying on the mercy of popping ping-pong balls—but many still believed that Boston’s infrastructure and 3-point mania would help patch together a respectably average team, perhaps even one that could make the playoffs.

My own stance was far more gloomy once the scale of Boston’s cost-cutting measures became clear. Talent talks. Size matters. Depth is critical. Coming into this season, it was hard to believe that Boston’s thin, raw, and vulnerable roster had enough to finish with a better record than the Cavaliers, Knicks, Pistons, Hawks, Bulls, Heat, Raptors, Bucks, or 76ers. Would they be worse than [gulp] the Hornets? Maybe!

So far, they’re 6-7, good for 11th in the conference, with more losses than all but the Wizards, Nets, and Pacers in the East. But many of their underlying metrics paint a more positive picture: Boston ranks top 10 in net, offensive, and defensive rating, and 30th in win differential, which means they have the largest gap in the league between their expected and actual record. (Cleaning the Glass has them on a 44.7-win pace, which is a little higher than their preseason over/under.)

With all of that said, though, and recognizing that it’s mid-November and there’s still a ton of basketball left to play, very little of what I’ve seen suggests that the Celtics are a 45-win team; in addition to some larger incentives Boston has that extend beyond this season, it’s fair to think this early in the year that they’re actually quite worse than their point differential suggests. In several ways, the Celtics have extracted the worst of Mazzulla Ball and then injected it into a lottery-level roster.

They rest at or near the league’s basement in fast break points, points in the paint, assist rate, opponent second-chance points, and, by an oceanic margin, free throw differential. They’re –129 at the charity stripe, while the Bucks rank 29th at –84. This is concerning stuff that gets even worse when you look at how their shot diet has changed without Tatum, Holiday, Porzingis, Horford, and Kornet.

Still jacking up a bunch of 3s—though much fewer from the corner—the Celtics now have the worst shot profile in the league. They rank 30th in at-rim frequency and first in midrange frequency and take more pull-up 2-point jumpers than every team except the Kings. This is not where you want to be. It’s a high-wire act; unless Jaylen Brown can continue to outperform Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, Kevin Durant, and every other NBA player from the midrange for an entire season, a critical chunk of Boston’s production will fizzle out.

The disciplined defense that propelled the Celtics to the NBA Finals by limiting their opponent’s free throw rate and dominating the glass has morphed, by necessity, into something more animated. They’re forcing turnovers at a rate they haven’t in a decade, pressing in the backcourt on 9.5 percent of their possessions—the fourth-highest mark in the league and way up from last year’s 2 percent. (Related to this: Minott and Hugo Gonzalez have been excellent in this role and might be long-term keepers if they can each hone a reliable outside shot and do stuff off the dribble.) The Celtics are turning those steals into transition opportunities at the 10th-highest rate in the league after finishing last season in 30th place and understand how important it is for them to avoid the half-court situations they’d been so devoted to over the past few years.

They compete like hell, irritate opposing ball handlers up and down the court, and still, on occasion, evoke the residue of a champion. Watch this peel switch between Derrick White and Payton Pritchard that completely flummoxed VJ Edgecombe:

When you combine that degree of pressure with an offense that takes care of the ball, you get a team that leads the NBA in shot differential by a significant margin. The Celtics have taken 122 more field goal attempts than their opponents this season. This was a key ingredient in the recipe Oklahoma City just followed to win a championship. The Celtics are also somehow protecting the rim as well as they did last year, and only the Pistons, Spurs, and Thunder are allowing fewer points in the paint. This is miraculous and, again, seems unsustainable—which is the case whenever Queta takes a seat.

In the aggregate, most of Boston’s lineups are beset by suspect personnel. In the season opener, Boston helped Edgecombe successfully mimic Dwyane Wade. They were then roasted by Keyonte George in a painfully close home loss against the Jazz and were completely outclassed by the Rockets, Knicks, and Magic.

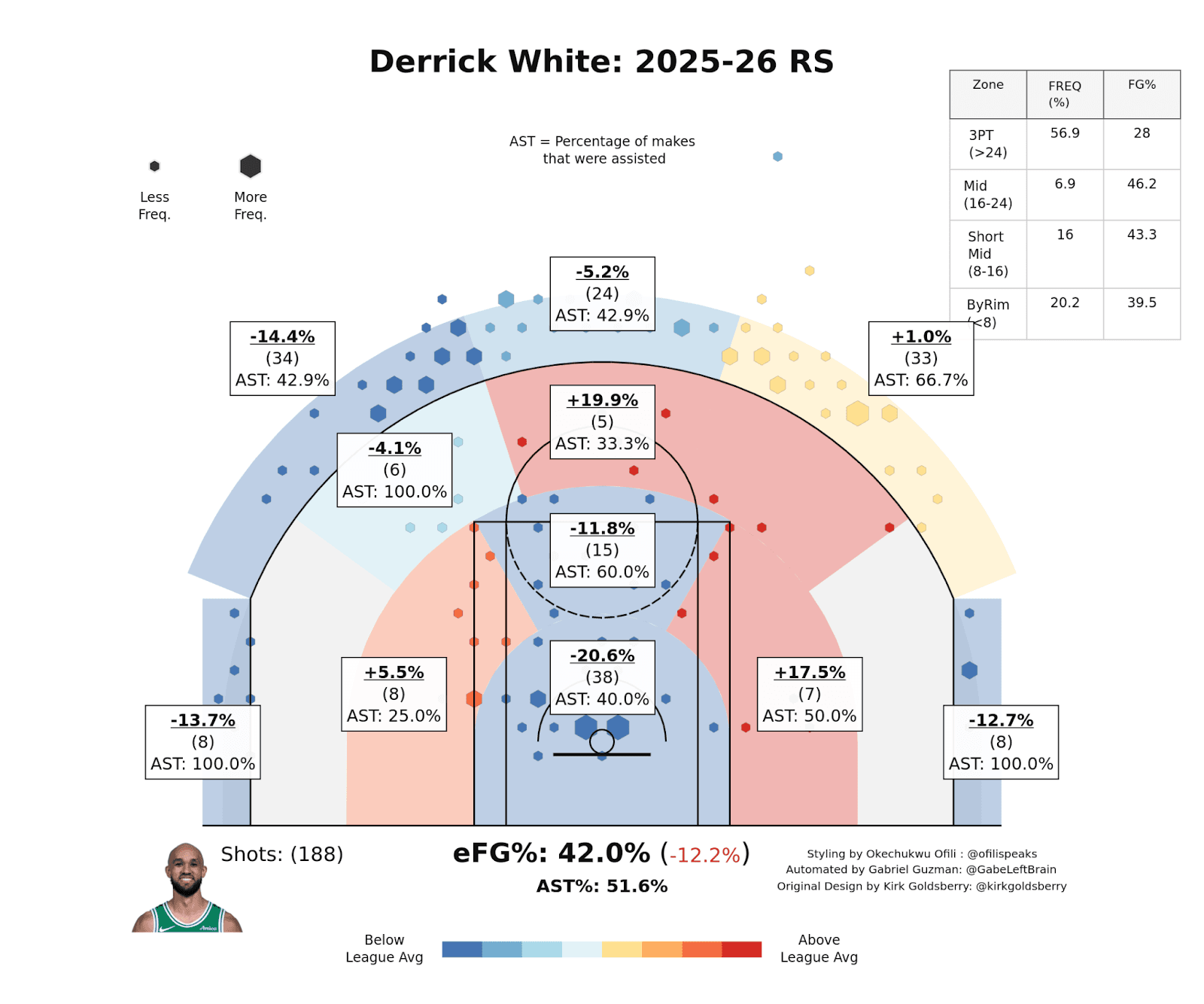

At their best, the Celtics look like a team that’s on the cusp of adjusting to a more practical identity, infusing the action with as much chaos as possible. Facing an average strength of schedule, they have two wins against quality opponents: at home against the Cavaliers and a narrow victory against the Magic. Boston has also blown out the Pelicans, Wizards, and Grizzlies—games that help explain its robust point differential. If you still think this is a playoff team—as some projection systems do—it’s probably because you expect them to snap out of their woeful outside shooting slump. Despite still employing several long-ball specialists, they’ve fallen from ninth to 24th in 3-point percentage. White has played better over the past couple of games but has still been, by almost any measure, one of the least efficient scorers in the league. Look at this shot chart. It’s not pretty:

Sam Hauser can’t shake a season-long cold streak, and Pritchard’s 3-point percentage is 9.7 percentage points below what an average player would convert with the looks he’s taken. (On the flip side, he’s shooting an absurd 68 percent in the nonrestricted area of the paint, unleashing a slew of fallaways and stepbacks that defenses have been unable to get a read on.)

Generally, instead of benefiting from the attention that was drawn by Tatum or Holiday—who’s currently averaging a career-high 8.5 assists per game in Portland—on drives to the basket, White and Pritchard find themselves having to create more for themselves inside the arc. Hauser’s limitations are pronounced.

Meanwhile, for the time being, Brown is striking an important balance between aggression and restraint. It’s early, but the 29-year-old has embraced difficult responsibilities that come with being a primary option for the first time in his career. Brown is actually running slightly fewer pick-and-rolls per game than last year but has the highest true shooting percentage and assist rate of his career. Nobody will confuse Brown with Tyus Jones, but for someone who suddenly has the third-highest usage rate in the entire league—and leads it in field goal attempts per 100 possessions—Brown has been composed and intentional, willing to give the ball up, get it back, and then attack a defense that’s suddenly bent out of shape:

He’s beyond comfortable curling off a wide pindown and either getting to the middle of the floor for a jumper or collapsing the defense and kicking out to an open shooter. In isolation, only SGA has finished more possessions than Brown, who’s been more efficient on those plays than the reigning MVP, James Harden, Luka Doncic, Anthony Edwards, Victor Wembanyama, and pretty much every other player who frequently eats one-on-one. The aesthetics and skill level Brown consistently displays are exquisite.

How much does any of it matter, though? With very little margin for error, this team is young, inexperienced, and deeply flawed. It still shoots 3s but can't rebound, defend without fouling, or rely on any elite playmakers to keep the floor raised on a nightly basis. And it’s all OK.

Nobody wants to hear this after a little more than a dozen games, but right now losses should be seen as wins; cleaning up a cap sheet and punching a ticket to the lottery should take precedence over anything that happens on the court. (One trade hypothetical that could work for everyone: Anfernee Simons to the Nets for Terance Mann. Boston adds $15.5 million to next season's payroll but ducks this year’s luxury tax. Conversely, Brooklyn takes on money over $12 million right now while clearing Mann’s money next year. It’s a win-win!)

Assuming Tatum will be back at full strength this time next year, it makes plenty of sense to add him and a blue-chip prospect to what already exists and see where it goes. Just ask the Spurs how that route went for them back in 1997.