The Enduring, Hedonistic Bromance of Robbie Robertson and Martin Scorsese

A new posthumous memoir by Robertson, ‘Insomnia,’ details his relationship with the director from the late 1970s until their final collaboration on ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’There is a posthumous memoir by Robbie Robertson out this week. It focuses on a sliver of time in the late 1970s, when the guitarist and songwriter best known for fronting the Band was involved in the following activities: (1) overseeing postproduction of The Last Waltz with Martin Scorsese; (2) watching movies and listening to music every night until the break of dawn with the director, who was also his roommate; (3) drinking and drugging with Scorsese and various other celebrities at locations all over the globe; and (4) bedding scores of beautiful women, including several famous actors.

It is called Insomnia. The cover features a photo of Robertson and Scorsese and a black-and-white color scheme, though it’s predominantly white. Neither the title nor the design is subtle. If you chopped this book up into a million little pieces, you could snort it and get a mild high.

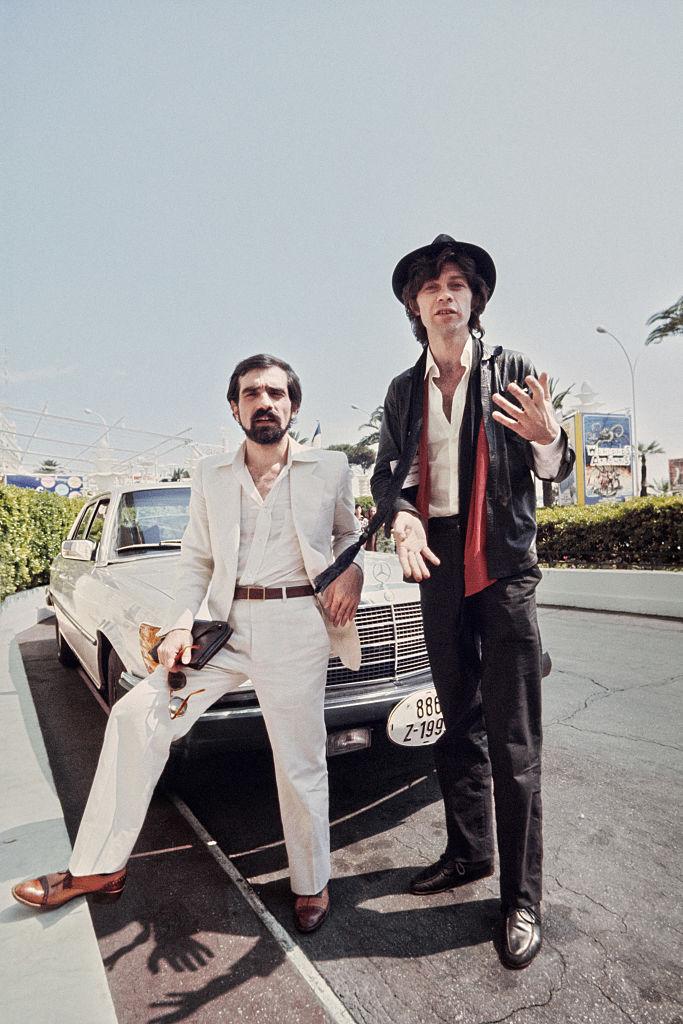

Does a book with such a narrow scope have much of an audience? I’m not sure. Robertson, who died in 2023, already has a memoir, 2016’s Testimony, that covers his life and career up until The Last Waltz, still his most famous and definitive project. I don’t know if there’s a big market for a second Robertson autobiography. What I do know is that the audience for Insomnia is me. I am a fan of Robbie Robertson, and I am a fan of Martin Scorsese. More importantly, I am a fan of Robbie Robertson and Martin Scorsese as pals, back when they lived together during tumultuous times in their marriages. They subsequently indulged in bad (and fun!) behavior for a few years while managing their respective personal and professional crises. “We became housemates, an odd couple, blood brothers, James brothers, and Marx Brothers all in one,” Robertson writes, with the same flair for elegant grandiosity that distinguishes his songs. “A blessed intervention against the banality of the ordinary and the obvious.”

Why do I, to a near-obsessive degree, care about this? It’s not like the period detailed in Insomnia corresponds with either man’s creative peak. Many of their greatest accomplishments occurred around the events of this book. Before he moved in with Scorsese, Robertson performed with Bob Dylan on one of the most historically important rock tours ever, participated in the informal sessions that birthed The Basement Tapes, and wrote and recorded “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “Up on Cripple Creek,” “It Makes No Difference,” and many other rock classics. Before he bunked with Robertson, Scorsese directed three of the greatest films of the greatest decade for American film—Mean Streets, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and Taxi Driver—all before the age of 35. And after Robertson moved out—a decision prompted, in part, by his hospitalization from too much partying—Scorsese made Raging Bull, possibly the best movie of the ’80s, while Robertson transitioned to work in Hollywood and, later, a solo recording career.

So why does this relatively aimless period in the middle of all that matter? Let’s start with this video, which you might have seen during one of its occasional rounds of virality. I don’t know how many times I have watched this, but I doubt any viewing has ever occurred before 10 p.m.

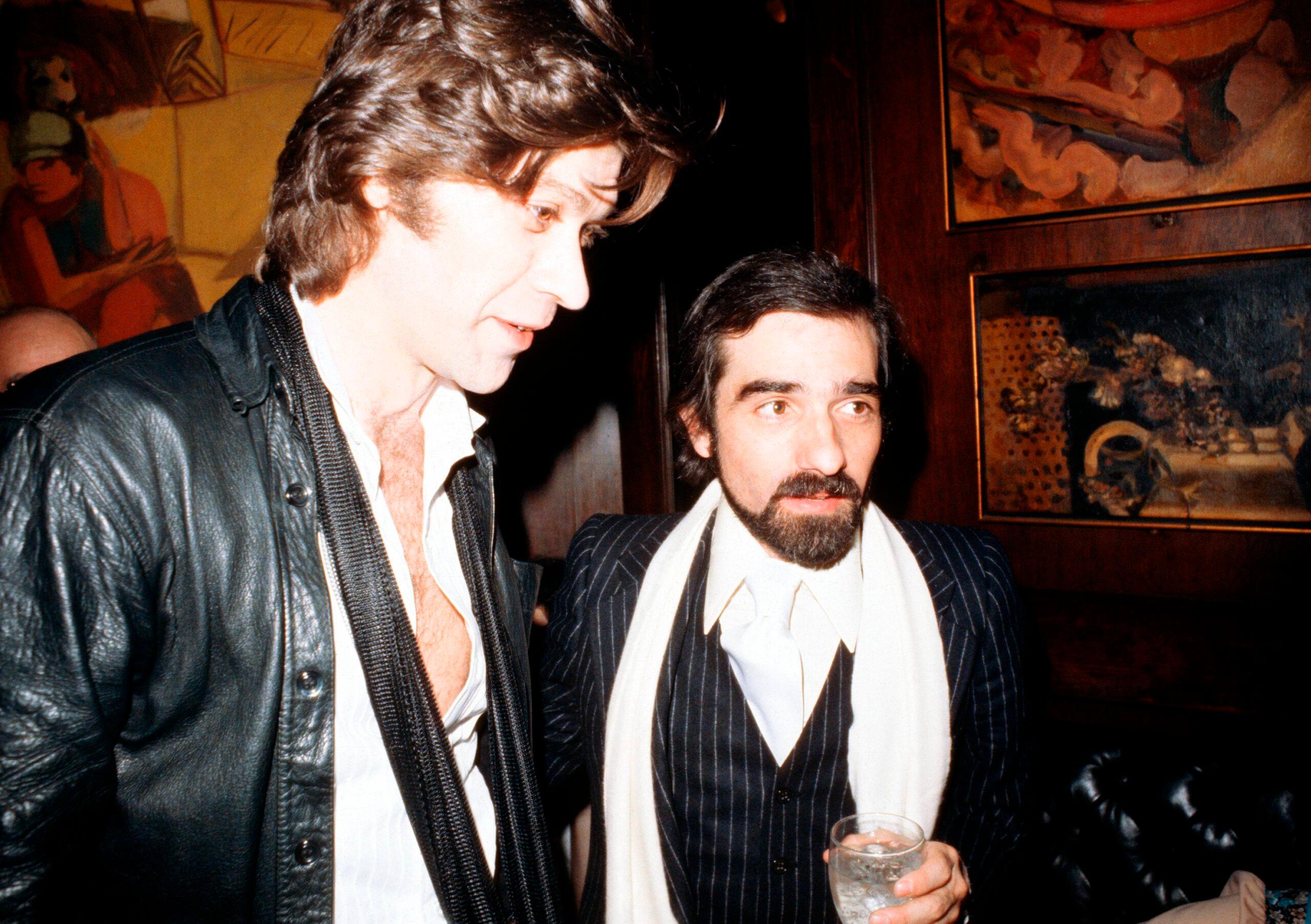

Here we have Robbie and Marty in a London hotel room. It’s 1978, and they’re on a promotional tour for The Last Waltz. Seated between them is Peter Hayden, an English director making a documentary about Scorsese for the BBC. It’s late, real late. So late that it’s almost morning, right before dawn. Robbie (tall, cool, handsome) is standing with a glass of what looks like white wine, and judging by his demeanor, it’s somewhere between his fifth and 15th helping.

“Maestro,” he says, referencing an affectionate nickname for his friend, “I want to play you a song before we knock off.”

Marty (short, jittery, also handsome) smiles. “Certainly,” he replies.

“This is by Van the Man,” says Robbie, who, upon pressing play on Van Morrison’s “Tupelo Honey,” immediately enters the kind of reverie that’s only possible when the human mind achieves the perfect balance of exhaustion, inebriation, and musical stimulation. He closes his eyes during the first verse, and when Van the Man hits the chorus, he takes a drag on his cigarette and smiles the sweetest smile. To his right, Marty also smiles while shaking his head and compulsively chewing on his pinky finger. Meanwhile, a gorgeous model, Lori Gleason, takes in the scene and yawns, a reasonable reaction given the hour. No matter. The universe at this very moment is composed only of Robbie, Marty, and “Tupelo Honey.”

When I received my promotional copy of Insomnia, I did a quick search for the “Tupelo Honey” incident. And here’s what Robbie wrote about it:

In this time that Marty and I had been hanging out, living together, working together, there were moments when we would be listening to something and we would look at each other to acknowledge: This is very special, this moment right now, listening to this music. The feeling sent a chill right through you. Here in our hotel, listening to “Tupelo Honey”—this was one of those moments. We were, as the Indians say, walking in the “beauty way.”

Reading this makes me understand why some people love Nancy Meyers rom-coms so much. For that audience, a love affair unfolding against a backdrop of immaculate kitchens and exquisite flower arrangements represents the pinnacle of romantic fantasy. For me, however, the ultimate bromantic fantasy is hanging out with Robbie and Marty in the late ’70s while vibing out to Van the Man. Walking in that “beauty way,” if you will. Can you imagine what that must have been like? The spell that video casts is more intoxicating than any drug.

Then, just like that, no matter how many times I watch it, the spell is inevitably broken.

“Dawn!” Robbie declares as Van the Man fades into the background and the video concludes. “We gotta pack! We gotta go!”

For a certain kind of person—a classic-rock partisan, a devotee of “New Hollywood” cinema, a reader of this very website, perhaps—Insomnia offers plenty of other vicarious, “hangout”-style pleasures. It opens with a vignette about Robertson attending a Muhammad Ali fight in New Orleans with Robert De Niro—sorry, I mean Bobby—Harvey Keitel, and Jake LaMotta. Later, the reader is whisked to London for a visit with Jack Nicholson during the making of The Shining, followed by a drop-in at George Harrison’s pad. Back home, Robbie and Marty encounter so many legendary filmmakers that their social calendar resembles a cinephile’s Letterboxd account: Sergio Leone, Akira Kurosawa, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Powell, Gillo Pontecorvo, Milos Forman, Wim Wenders, and so on.

If I weren’t a sucker for this sort of thing, I might accuse Robertson of being an inveterate name-dropper. But the bulk of Insomnia is centered on his relationship with Scorsese, which started with a meeting in 1973 at a screening of Mean Streets but didn’t begin in earnest until Robbie tapped Marty to direct The Last Waltz three years later. Robbie sensed, correctly, that Marty had an intense connection with music from the inventive ways he used songs of every genre in his previous films.

The filming of The Last Waltz was covered by Robertson in Testimony, so Insomnia picks up during the editing process, when Robbie suddenly needed a place to stay after an impasse in his marriage to his then-wife, Dominique Bourgeois. Scorsese, similarly, was having problems with Julia Cameron, his second spouse, whom he had just married in 1976. (They eventually divorced, while Robertson later reconciled with Dominique until their union ended in 2003.)

As Robertson recalls, Scorsese was quick to invite him to move in, even though they were more like professional collaborators than personal friends at that point. “As I registered the news, I thought, Wow, he’s kind of in the same sinking boat as me,” he writes.

They put their minds off this slow-motion drowning with nightly routines of movie watching and music listening. Marty would pick the films (Visconti or Buñuel, one of Robertson’s faves) and Robertson the tunes (Ray Charles or George Jones, even though Mean Streets cowriter Mardik Martin made fun of the latter). In each other, they saw what the other guy wanted to be. “He had a quiet yearning to be a great musician,” Robertson says. “And the magic of making movies had lived inside me for as far back as I could remember.”

Insomnia gets a lot of mileage out of exploring their so-called “odd couple” dynamic. Robertson describes Scorsese as “a cross between Che Guevara and George Patton—relaxed, but in control of the battlefield.” Marty, actually, doesn’t come off all that relaxed. Hints of his volatility linger throughout the book, though it’s not Robertson’s style to spell out the darkness in either man’s life with too much specificity. (Like how he refers to cocaine euphemistically as a “little pick me up.”) As Robertson tells it, Scorsese’s inner turmoil was rarely unleashed at his roommate’s expense, except when he turned up late for their evening screening and his dinner turned cold. (“I appreciated Marty’s concern about my nutritional well-being,” Robertson offers, dryly.) This slow-burning anger did, however, sometimes manifest in Scorsese’s relationships with women; Robertson recalls one busted-up hotel room in the aftermath of a spat with Liza Minnelli, Marty’s lover during the production of 1977’s New York New York. Elsewhere, Robbie spies his friend chasing “a nice-looking brunette I didn’t know” down the driveway in only his pajama top. “His white legs were just a blur going by,” he remembers.

If women could be a problem for Scorsese, they were a balm for Robertson. The topic he is most candid about in Insomnia is his way with the ladies. He names the famous actors he romanced while estranged from his first wife, including Geneviève Bujold, Tuesday Weld, and Summer of ’42 star Jennifer O’Neill. (He also attempted to hook up with Sophia Loren, who was married at the time, but was gently rebuffed.) No less an authority than Warren Beatty acknowledged Robertson’s long list of trysts, inviting him to stay at his new Mulholland Drive mansion. But Scorsese swiftly intervened. “Just then,” Robertson recalls, “Marty turned and said, ‘We’ve got a screening room. We’re all set up. Our own chef, incredible sound system ...’”

The bedroom tales speak to Robertson’s well-established egotism, which fans and detractors alike have recognized since (at least) witnessing all those worshipful glamour shots in The Last Waltz. (That was a particular topic of derision for Robbie’s onetime best friend and bandmate Levon Helm, who hated the movie for its focus on Robertson and referred to Scorsese in his own memoir as “the dummy.”) But the casual sexual escapades also underscore that the real love affair at the heart of Insomnia is, in fact, between Robertson and Scorsese.

To Marty, Robbie must have seemed like a figure out of the Westerns and film noir pictures he grew up on. With his smoky voice and dark hair, Robertson resembled the sexy, guitar-playing outlaw portrayed by Gregory Peck in 1946’s Duel in the Sun, a formative film of Scorsese’s youth. And then there’s the matter of Marty’s famous fanaticism for music, particularly guitar-heavy, bluesy rock. Robertson put this former asthmatic kid, forever the outsider aesthete who could listen to records but never live inside them, directly into the heart of the rock world in a way precious few non-musicians ever experience.

As for Robertson, Scorsese was his ticket out of that world. In the book, he alludes to potential reunions with his old partners in the Band that never materialized, culminating with a phone call to Helm, where the irascible drummer is dismissive about a possible role in the Loretta Lynn biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter. While Helm was later cast in the movie, Robertson identifies this moment as the catalyst for deciding he “wanted new challenges, new quests, new bloods, new roads.”

While Robertson doesn’t say it outright, the implication is that he was joining up with a new partner. And that collaboration, unlike his involvement with the Band, lasted well beyond the ’70s.

When I interviewed Robertson in 2018, I was struck by how much he talked about movies, even though the purpose of our talk was a recent reissue of the Band’s 1968 debut, Music From Big Pink. No matter the question, the answer always seemed to circle back to cinema. He recalled how, when he lived in New York City, he frequented a bookstore that sold screenplays, which prompted him to start collecting scripts. One day, he stopped to look for Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, and the clerk called out for a coworker to locate it. Her name was Fanny, a name Robertson filed away for when he later wrote “The Weight.” Though, when he looked back on the story more than 50 years later, he dwelled less on the iconic song than on a potential alternate career path. “If I hadn't gotten so caught up in music at such an early age and playing professionally by the time I was 16 years old, I would've probably veered into movie land,” he admitted.

Insomnia charts the beginning of that mid-career veer into movie land, with The Last Waltz and then Raging Bull, for which Scorsese recruited Robertson to write and record some incidental music for a nightclub scene. He also discusses 1980’s Carny, a mostly forgotten character study he starred in, produced, and cowrote. A real “They don’t make ’em like this anymore” kind of movie, it follows an unlikely love triangle involving Robertson, a low-level carnival operator; a clown played by Gary Busey; and a teenage runaway portrayed by Jodie Foster. If that sounds like the opposite of “commercial cinema,” it might explain the film’s paltry $1.8 million gross, about a third of its budget.

Robbie had better luck sticking with Marty. Had Robertson lived longer, it’s possible Insomnia would have further explored his work with Scorsese in the ’80s and beyond. (He was, according to his final published interview, still working on the book when he died in 2023.) They made, in all, 11 movies together. Sometimes Robbie served as a film composer, a role that began with 1986’s The Color Of Money. You hear Robertson’s soulful moan over the opening credits, and his guitar slashes and warbles throughout as Paul Newman and Tom Cruise hustle from one pool hall to the next. (He also cowrote the film’s signature song, the Eric Clapton Michelob rock standard “It's in the Way That You Use It.”) A more personal form of songwriting occurs on the soundtrack for 1983’s The King of Comedy, which Robertson produced. “Between Trains” was his first lead vocal on one of his own songs, revealing the limited but expressive throaty tenor he withheld when the Band’s trio of excellent vocalists was at his disposal. Lyrically, it outlines a state of transition that was more reflective of Robbie’s life at the time than Rupert Pupkin’s. “If I'm too young to learn / Or too old to change / I guess I'll always be / Between trains.”

More often than composing music for Scorsese, however, he was curating it, either as a consultant, music supervisor, or—as he was frequently billed—executive music producer. As someone who often rewatches Scorsese movies just to pay attention to the music, I can’t help but speculate on which tunes are “Robbie” songs and which ones are “Marty” tracks. On the Casino soundtrack—you can see Robbie pictured with Marty in the liner notes—you have Muddy Waters and the Staple Singers, both of whom appear in The Last Waltz. (There’s also Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s “I Ain’t Got No Home,” a song covered by the Band on 1973’s Moondog Matinee.) And then there’s Roger Waters’s The Wall—Live in Berlin version of “Comfortably Numb,” which was fairly obscure until it appeared in 2006’s The Departed. That rendition famously features Van Morrison on the soaring chorus, though if you listen close, you can also hear Robertson’s former bandmates Rick Danko and Levon Helm on the harmonies.

From the Marty side, as detailed in Rebecca Miller’s excellent 2025 documentary, Mr. Scorsese, he literally wrote Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” into the screenplay for Goodfellas. He was also a fan of Phil Collins’s “One More Night,” which he played late into the evening while making The Color of Money, according to Ian Christie and David Thompson’s book Scorsese on Scorsese. (This is, I contend, one of the great needle drops in the Scorsese canon.)

In 2014, while promoting The Wolf of Wall Street, Robertson offered some insight into their process. “I go through hundreds and hundreds of pieces of music over a period of months and build what I call Marty’s Juke Box,” he told Fast Company. “He has all these songs so he can try different things in different places. Some songs are for specific scenes, and certain things are just like ‘Marty you gotta hear this.’”

For Wolf, Robertson pushed for fire-and-brimstone blues numbers like Elmore James’s “Dust My Broom” and Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightning,” which play against the film’s late-’80s/early-’90s milieu while providing a sense of Old Testament–style reckoning. Those songs are also in Robbie’s stylistic wheelhouse, though he could pivot to different styles if the film demanded it. For 2010’s Shutter Island, he stacked Marty’s Juke Box with modern classical music pieces by composers like Krzysztof Penderecki and John Cage.

On each movie, Scorsese took the music Robertson collected and painstakingly matched it with his images, an undertaking that could take a long time. (Wolf, for example, was in the editing room for a year.) I wonder if this ever felt like those late-night “walking in the beauty way” hangs from the late ’70s. Was the work an excuse to be together, or vice versa?

In Mr. Scorsese, the ’80s are depicted as the filmmaker’s most trying decade, the period when he was furthest from the mainstream. The same can be said of Robertson and his proximity to the music world at that time. For years, he rented studio space at the West Hollywood studio Village Recorder—the same place where the Band backed Bob Dylan on 1974’s Planet Waves—for $12,000 a month. It was the start of him easing back into making a proper album again, but what was his place now?

By 1986, he was signed with Geffen, the label that would soon make a mint from Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction. That’s the kind of album most record executives could justify spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on, not a long-gestating song cycle from a 40-something-year-old boomer icon. Robertson plowed forward anyway, landing on Daniel Lanois as his producer. A French Canadian associate of Brian Eno, Lanois was newly rich and industry famous for coproducing a pair of prestige blockbusters, 1986’s So for Peter Gabriel and 1987’s The Joshua Tree for U2. Around the same time, Lanois clearly pulled from that work for Robbie’s self-titled solo debut, which radically broke from the rustic naturalism of the Band for an elaborate sonic tableau that resembled an amalgam of So’s and The Joshua Tree’s impeccable, cathedral-like art rock. (Gabriel and U2 both appear on the record.)

Upon its release in 1987, Robbie Robertson was greeted in some quarters as a masterpiece. (Rolling Stone named it one of the best albums of the ’80s.) But a lot of people hated the production, which seemed to purposefully obfuscate Robertson’s persona with the Band. Greil Marcus bemoaned that the album’s sound—so heavy on Lanois trademarks like reverb and processed effects—made it “hard to discern an actual human being behind any of it,” while Robert Christgau concluded that Robertson “always took himself too seriously.” Decades later, however, I would argue that Robbie Robertson not only slots next to the best of the Band but also holds up as an authentically important record in a subgenre I call “futurist Americana.” This refers to albums that Lanois subsequently produced for Bob Dylan (Oh Mercy, Time Out of Mind), Emmylou Harris (Wrecking Ball), and Willie Nelson (Teatro), as well as the next generation of acts inspired by those artists, like Wilco (Yankee Hotel Foxtrot) and the War on Drugs (Lost in the Dream). The common denominator is using the latest technology to create music that paradoxically sounds ancient, slightly broken, and reminiscent of a distant, dusty past.

Robbie Robertson is another chapter in the Robertson-Scorsese partnership. Marty directed the video for “Somewhere Down the Crazy River,” Robbie’s most cinematic song and the one where he flirts aggressively with self-parody, as he purrs lustily about “laying in the back seat listening to Little Willie John” while fondling the fetching Lone Justice singer Maria McKee. I also suspect that Scorsese’s decision to hire Gabriel to score The Last Temptation of Christ, which came out the following year, had something to do with that album, which has an ecstatic intensity similar to Gabriel’s music for the film.

But the most important aspect of Robbie Robertson, as it pertains to the Robbie-Marty union, is the Native American imagery. It’s most evident on the best song (and one of Robertson’s greatest overall compositions), a heartbreaking ballad couched in an Indigenous phrase for reconciliation: “Broken Arrow.” Born to a mother of Cayuga and Mohawk heritage who was raised on the Six Nations of the Grand River reservation outside of Toronto, Robertson explained to The Los Angeles Times in 1987 that his cultural background always “intrigued” him but that he “didn’t feel right imposing this on the Band.” However, for his cinematic work with Scorsese, it would become the subject of their last big collaboration more than 35 years after first teaming up.

For Killers of the Flower Moon, Robertson drew on memories of hearing music at Six Nations, “while I’m sitting there and my relatives are all sitting around with their instruments and singing and breathing,” he told Variety. That said, what he wrote for the film was not, he confessed, “stereotypical Indian music,” but rather gnarled-up blues with stinging guitar licks, like the tunes he stumped for during The Wolf of Wall Street. “A swarm of guitars,” was how he put it, “the sounds and textures and rhythmic feels, all just kind of swamping around one another.”

He knew, after all, that Marty likes guitars. But Scorsese also needed Robertson’s music to convey a constant feeling of underlying menace. “Give me something dangerous and fleshy” was Marty’s command, so that’s what Robbie gave him. That swarm of guitars constantly lurks in the sound mix, steadily pulsing and pounding, like a tiger hiding in the bushes. It’s the spine of a movie that has the feel and scope of a mythic Robbie Robertson song about the underbelly of America. Like “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” where he writes, without judgment or excuse, about a racist Southerner who is humiliated by the Confederacy’s defeat. In Killers, there’s a similar tension in how Scorsese treats his protagonist, the oafish serial murderer played by Leonardo DiCaprio who victimizes his wife in the worst possible ways but also sincerely loves her.

Killers of the Flower Moon is Robertson’s finest work as a film composer and eventually garnered an Oscar nomination. (He lost to Ludwig Goransson for Oppenheimer.) But Robbie didn’t live to see the film’s release. Robertson had been in remission from prostate cancer for 25 years, but the disease came back in 2022 and spread to his spine and brain. He died on August 9, 2023, two months before the film’s opening.

Scorsese dedicated it to him. Scorsese also offered a different kind of tribute to Rolling Stone, writing a stream-of-consciousness remembrance that unfolds more like a screenplay operating on dream logic than a normal eulogy. He calls himself the Bob Hope to Robbie’s Bing Crosby, an old movie geek reference his friend would have appreciated. He speaks of the art they experienced together—Visconti’s Senso, Samuel Fuller, Willie Dixon, even the Sex Pistols, which Marty used to blast around the house to Robbie’s annoyance. (“They have no musicianship!” he complained.) And he talks about how every Thanksgiving they would get on the phone to reminisce about The Last Waltz.

At one point, Marty puts himself back in that hotel room from 1978. “The sun is coming up. The only thing left to do was to put on ‘Tupelo Honey,’” he writes. “That’s what always happened. Van and ‘Tupelo Honey.’ It was sort of our sign off.” For his 80th birthday, Marty adds, Robbie even brought out Van the Man himself to sing as a surprise.

What a friend. What a love affair. But now it’s over. Marty concludes with this: “I don’t think I’m going to listen to ‘Tupelo Honey’ anymore.”