On Sunday, the Packers closed out the first half of their game against the Cardinals with a seven-second scoring drive. After a touchback put the Packers on their own 35-yard line, quarterback Jordan Love completed a 22-yard pass. And then, out came the field goal unit for a 61-yard attempt that went through the uprights with air to spare, setting a franchise record.

That make by 26-year-old Lucas Havrisik, en route to a 27-23 Green Bay win, wasn’t the only successful 61-yarder on Sunday. The Cowboys’ Brandon Aubrey hit one, too, for the fifth 60-plus-yard field goal of his 2.5-year career—already the most in NFL history. Aubrey, whom Tom Brady compared to Steph Curry and Shohei Ohtani, is a two-time All-Pro. Havrisik, by contrast, is newly employed. An injury replacement signed the day before his Packers debut on October 12, he is a few weeks removed from looking for part-time teaching jobs. As the top comment on the Reddit post about his long-distance kick said, “We’ve got substitute teachers kicking 61 yard field goals. What’s going on lmao.”

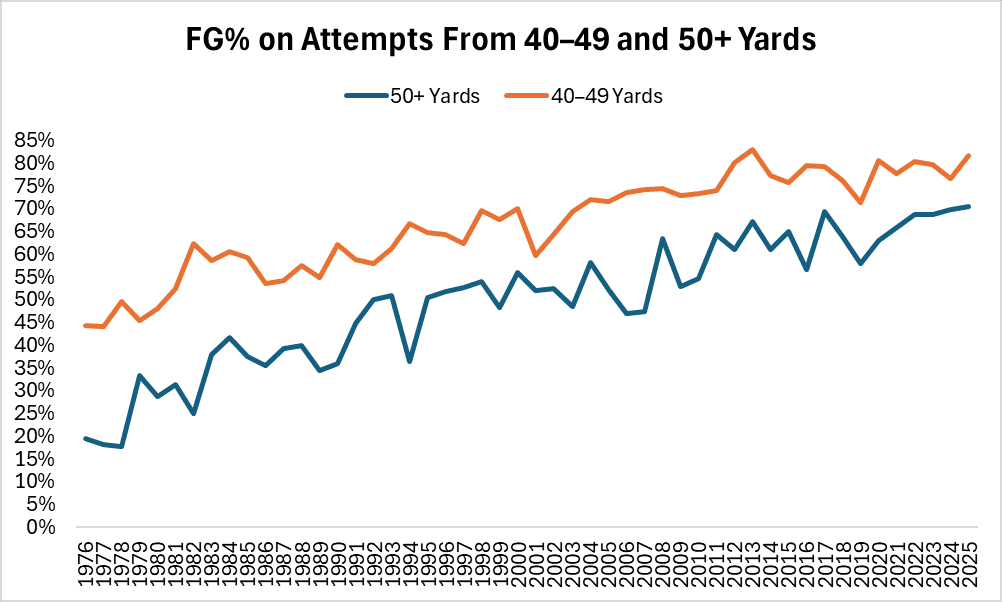

What’s going on is that kickers—even almost unknown ones—have gotten really good, thanks in part to their own talent and in part to new rules that allow for advance preparation of kicking footballs (a.k.a. K-balls). Consequently, as the AP put it earlier this month, “The 50-plus-yard field goals that once were a rarity in the NFL are now as routine as far shorter kicks a generation ago. The range for many kickers now exceeds 60 yards, changing late-game strategy in a major way.” A graph of field goal completion percentage from 40 to 49 yards and 50-plus yards over the past 50 seasons tells the same story.

Fifty seasons is a nice, round number, and conveniently, it also takes us back to 1976, a year of great significance to this story. That’s when Disney (accidentally) envisioned the future of football.

The league’s current kicking acumen may be unparalleled in the real-life NFL, but as I recently learned, it’s not without precedent in depictions of the fictional NFL. The movie Gus got there first.

On a late September podcast, I praised the NFL’s revamped dynamic kickoff rule (which has led to many more returns) while also lamenting that it’s summoned more manifestations of “my nightmare vision of football,” in which “you get the ball back and you immediately kick a field goal, and then the other team does the same thing.” Although I acknowledged that this dystopian football future hasn’t fully arrived, I noted that what qualifies as “field goal range” has expanded to such a degree that “every now and then, you have a [scoring] drive that just feels like, ‘That’s it? They barely drove anywhere!’”

A few days later, I got an email from listener Bobby Goldstein, who wrote, “About what you hinted at about teams just getting the ball and immediately kicking a field goal … there was a fictional treatment of this from my formative years, a Disney movie called Gus.”

Rocky, Network, Taxi Driver, All the President’s Men … Gus. These are all movies released in 1976, but that’s where the similarities among the first four and Gus end. Granted, Gus—a kid’s football flick about a mule who kicks field goals, directed by Disney regular Vincent McEveety, produced by Walt Disney’s son-in-law (and former NFL player) Ron Miller, and starring Ed Asner and the comedic acting duo of Don Knotts and Tim Conway—was the fourth-highest-grossing release of the summer of ’76. But that summer predated me by more than a decade, and I wasn’t aware of the movie before Bobby’s email. Once he made me aware of it, I interrupted my daughter’s Disney+ viewing of Frozen, Bluey, and Doc McStuffins to check out this sports not-quite-classic, glimpses of which can be seen in the jarringly modernized trailer below.

At the beginning of the movie, amid a montage of inept plays by the NFL’s lowly “California Atoms,” an assistant to cigar-chomping Atoms owner Hank Cooper (Asner) tells him about a miraculous mule from the former Yugoslavia who can “kick hundred-yard soccer goals,” which seems “kinda terrific.” The weary Cooper replies, “Yeah, especially since we got nobody that can kick any kind of ball 5 yards.”

Cooper grudgingly sends a scout to see the hooved hot prospect, the titular Gus (played by a 12-year-old, 700-pound, custom-jersey-wearing mule of the same name). The scout sends back a breathless report about Gus’s accuracy, and the desperate Atoms sign Gus, mostly as a halftime-show publicity stunt. But desperation sets in after they lose 41-0 to the Cleveland Browns (who had already morphed into symbols of football futility), after an easy field goal attempt goes awry as the Atoms’ kicker misses the ball and sends his own shoe flying through the uprights, complete with a slide-whistle sound effect.

Meanwhile, the compulsively gambling owner, who’s deeply in debt to his mobster bookies, makes his boldest bet: If the Atoms win the Super Bowl, his debt will be forgiven, but if they don’t, he’ll lose the team. The owner soon insists that Gus, his secret weapon, make a kick in a game against the Packers, which confounds his neurotic, hapless head coach (Knotts) and elicits an objection from an official. “The mule stays in, and he kicks,” Cooper declares.

Lo and behold, the refs decide in the Atoms’ favor, in a ruling read by a broadcaster played by Johnny Unitas, who appears in the film along with fellow football luminaries Dick Butkus and Dick Enberg. “The game is to be played by two teams of 11 players each,” Unitas relays. “The rule book does not define the word ‘player.’ Therefore, a player could be a man, a woman, or anyone a team chooses to represent them on the field. And so, ladies and gentlemen, the mule, Gus, will be allowed to play.”

Essentially, Gus kicked so that Buddy from Air Bud could dunk (and catch, shoot, hit, spike, and so on). High jinks ensue, love blooms between the owner’s assistant and Gus’s holder, and the Atoms win the Super Bowl, thanks mainly to the mule described as a four-legged George Blanda and inspired, perhaps, by the trailblazing, European, soccer-style NFL kickers of the ’60s and ’70s such as Pete Gogolak and Garo Yepremian.

I didn’t see Gus in my formative years, so I can say with clear eyes (and full hearts) that Gus isn’t good, even by children's movie standards. The acting is exaggerated, the editing is awkward, the rear projection is painfully dated, and the plot is predictable. Worst of all, it’s not funny, aside from the preposterous premise. Although the poster proclaims, “It’s the league’s leading laugh scorer,” it rarely made me smile. “Even the mule seems bored,” wrote Roger Ebert in his two-star review.

Although Gus is one of the few mules to make Wikipedia’s list of “Fictional mules” and the movie clearly lodged itself in the memories of the kids who saw it in theaters or on home video, it hasn’t really lingered in the cultural consciousness. In October 2020, Bill Maher invoked it to compare Donald Trump’s attempted exploitation of electoral loopholes to the California Atoms’ mule-related rules lawyering—and even Maher called it “that Disney movie from the ’70s I keep talking about that no one remembers.”

It would be a stretch to say that Gus predicted Trump, but the movie is looking pretty prescient on the football field these days, notwithstanding the minor matter of the mule. So are we heading for a real-life Gus scenario? Following in the footsteps of the makers of Gus, who thank the NFL in the film’s credits for “assistance in the football sequences,” I put my question to Michael Lopez, the NFL’s senior director of football data and analytics. Lopez explained:

There are several things at play right now in the NFL: Possessions per game (or drives per game) are at historic, all-time lows. This is largely because incomplete passes are at all-time lows, which means that the clock never stops. Teams get about one less possession per game than they did a decade ago. Average drive start (currently the 31-yard line) is at an all-time high. This is mostly the new kickoff rule/incentives for kickoff returns. All over the field, teams are going for it instead of kicking it. This means punts are at all-time lows (we've lost over a thousand punts versus a decade ago)! So, field goals are at all-time highs. But that's a function of several things besides kickers getting better ... and, of course, because kickers are better. It is very top of mind for league execs that we can't make field position too good, and some already bemoan that teams need one first down and can kick a field goal.

As Nate Silver, creator of the new ELWAY NFL forecasting system, noted on X last week, “If you're anywhere past the opponents' 45-yard line or so, it's riskier to gamble with downfield passes that may result in an interception because the expected value of the possession is higher when you're almost assured of a field goal. And really, these considerations apply even before then. With teams also starting out with better field position with the new kickoff rules, they're often in a position where two first downs = field goal range.”

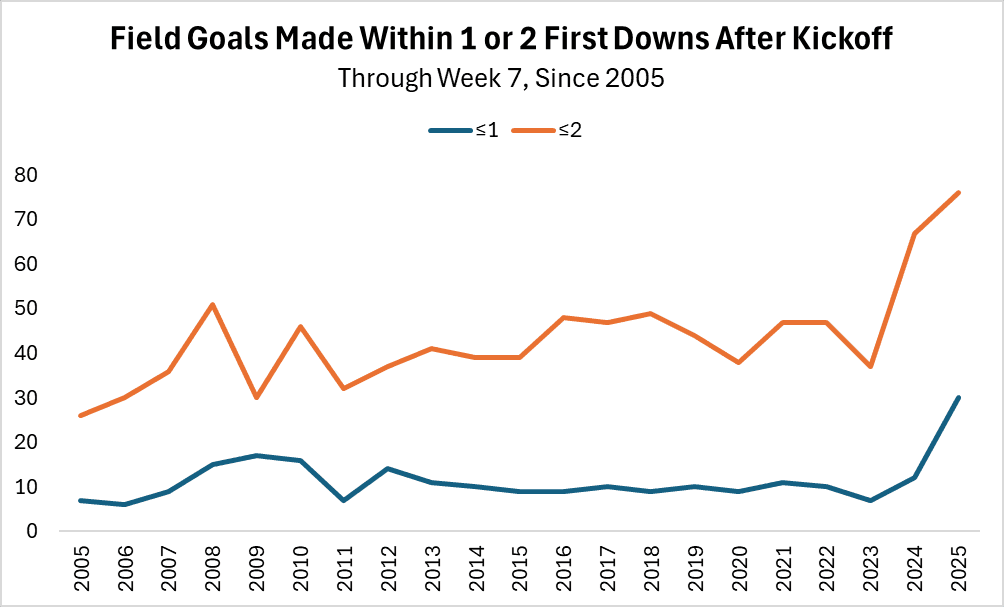

Lopez sent me some hard data on this. Through Week 7 of this season, there were 30 field goals made within one first down on a drive beginning after a kickoff, up from 12 last year and more than twice the highest number through the same point of any season since 2010. (The average total back to 2005 was only 10.4.) The number of field goals made within two first downs after a kickoff, 76, was also a new high, albeit only a modest uptick over last season, when the initial introduction of dynamic kickoffs caused a sharp spike.

In my quest to pester some of the finest football minds about whether a dumb Disney movie anticipated today’s NFL, I also bugged ESPN’s Bill Barnwell, my old Grantland colleague, who kindly called it an “excellent question.” Barnwell observed that a kicker who could drill a field goal from anywhere would be immensely valuable, which is obvious to anyone who watched the Atoms go from worst to first. He continued:

The more meaningful impact has been on late-game scenarios, where kickers can really be weaponized on short drives against prevent defenses in situations where a field goal either ties or wins the game. Combine that with the new league kicking rules, and you might realistically be able to pick up 20 yards and be in position where you have a very viable shot at hitting a field goal. Teams have quickly realized that the new meta with kickoffs is to kick deep without landing the ball inside the end zone for a touchback, forcing the other team to attempt a return. In 2025, the average drive that doesn't end in a touchdown or with time expiring starts on the 29-yard line and gains 22 yards, meaning it makes it to the opposing team's 49-yard line. That's a 67-yard field goal, which is very conveniently one yard past the NFL record for the longest field goal in a regular-season game.

So, right now, the average drive that doesn't produce a touchdown ends up in position to attempt what would be the most impressive kick in NFL history. That makes me believe that we're probably not close to a time where every drive ends up in position to make a field goal. But could we get to that point if kickers continue to improve, teams invest more in special teams coaching, and league ball rules continue to evolve in ways that favor kicking? Maybe. My instinct is that the league would respond to this by reducing the distance between the goalposts before we ever got to that point. But it's fun to consider.

It was certainly fun for me. (More fun than watching Gus, at least.) What wouldn’t be fun is a world where actual kickers render drives irrelevant by replicating Gus’s field goal feats: successfully going for three from his team’s 12-yard line on fourth-and-18 to beat the Packers; sniping from the 9-yard line on fourth-and-24 to top the 49ers; recording 14 field goals in one game.

So when will the kickers get Gus-like, if they haven’t yet? Field goal aficionado Stefan Fatsis, author of A Few Seconds of Panic (which documented his stint as a backup placekicker for the Denver Broncos), told me, “I think 75 is well within range, and I think we’ll see it pretty soon happening at the end of a game or the end of a half, when the opportunity is there.” After all, an about-to-be-fired Lane Kiffin sent the Raiders’ Sebastian Janikowski out to attempt a 76-yard kick, into the wind, in the comparatively kicking-challenged year of 2008.

“Inconceivable!” Jim Nantz exclaimed as he watched Janikowski line up. Back then, the record (which Janikowski later tied) was 63 yards. Now it’s 66, not counting the 67-yarder Evan McPherson nailed this month (which was disallowed due to a timeout) or the 70-yarder Cam Little made this preseason. Converting from 70-plus yards is still improbable, but it’s hardly inconceivable. And splitting the uprights from a team’s average starting position seems downright inevitable. Especially once you’ve watched Gus.