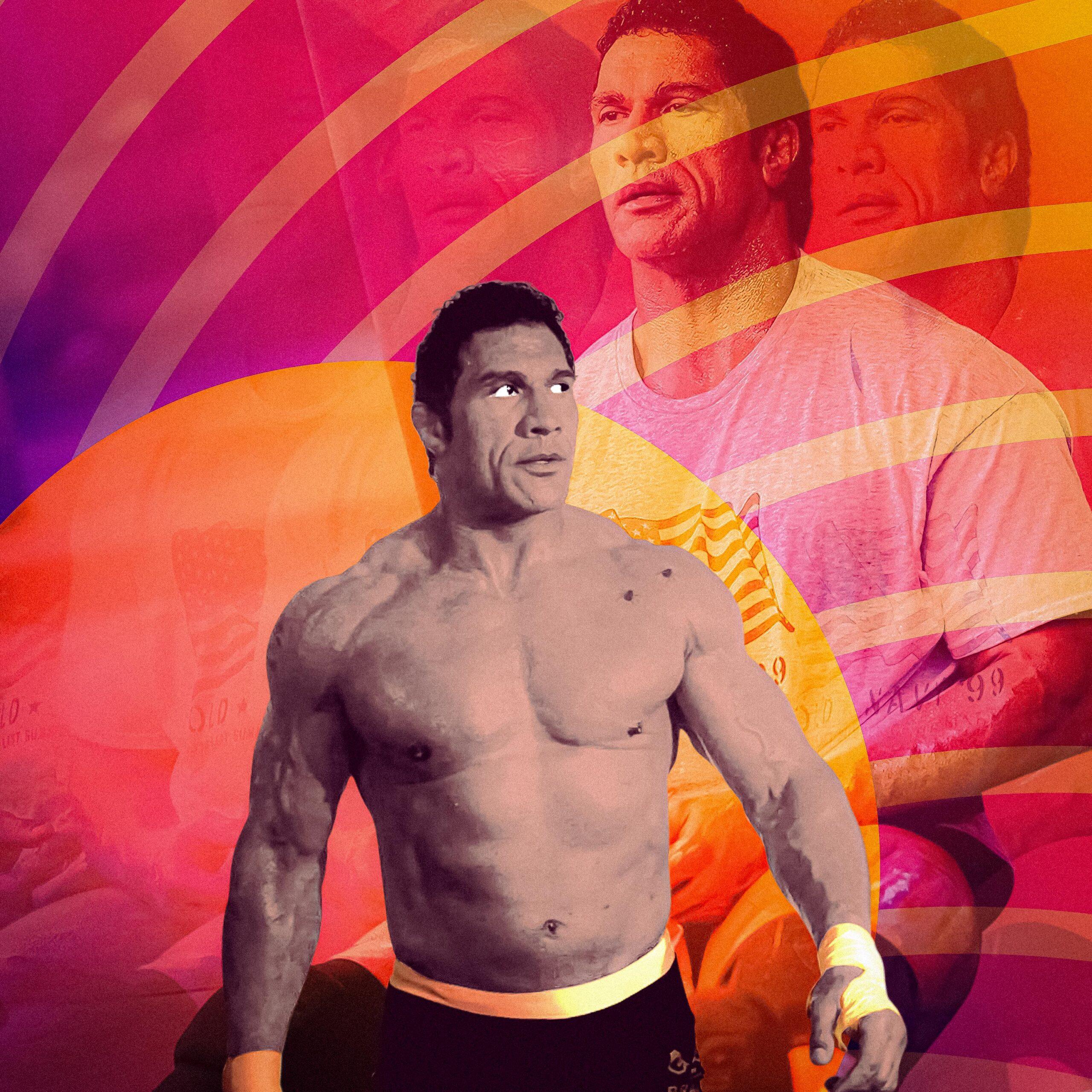

As the former UFC and Pride combatant Mark Kerr in Benny Safdie’s The Smashing Machine, Dwayne Johnson is a walking contradiction: He’s seriously bulked up yet somehow smaller than life, a stranger in his own tanned and tautly muscled skin. Whether working with a top-tier American director can redeem the Rock for having one of the most god-awful A-list filmographies in recent memory—fun fact: Red Notice and Red One are, in fact, different piles of streaming-service slop—there’s no doubt the film is Johnson’s best showcase since Pain & Gain. It’s also the first time he’s come anywhere close to disappearing into a role—no mean feat for a global icon who became famous by referring to himself in the third person. On one level, the casting of a brand-name pro wrestler as a well-known mixed martial artist is completely on the (prosthetic) nose. At the same time, it’s fascinating to watch a superstar work successfully to sublimate his charisma in the service of realism.

Authenticity is paramount in The Smashing Machine, which debuted at the Venice Film Festival and earned Safdie a Best Director prize in his solo filmmaking debut. The film is a fictionalized companion to John Hyams’s 2002 documentary of the same name, which introduced viewers outside the MMA bubble to its subject’s hard-luck story. It takes place from 1997 to 2000, during which time Kerr was arguably the most acclaimed MMA fighter in the world; it traces his trajectory from a crushing, high-profile loss in Tokyo to an attempted comeback imperiled by bad behavior out of the ring. In a 2021 interview with The New York Times, Hyams sized up Kerr—a former NCAA champion wrestler who arguably missed the Olympics due to injury and turned to mixed martial arts for cash—as a man who was “really good at something that [he hates],” a berserker on autopilot whose ambivalence didn’t make him any less effective at pulping his rivals.

It’s a fascinating observation, and even though he’s nearly 20 years older than Kerr was during the events depicted in the film, Johnson inhabits it fully from the inside out. The illusion begins with an uncanny hair and makeup job; the actor completes it by altering his body language from a front-running strut to a hapless amble and subtly pressurized line readings. “Do you hate each other when you fight?” asks an older woman waiting alongside Mark at a doctor’s office. “Absolutely not,” he replies from behind a black eye, sounding only semi-convincing and an awful lot like a guy doing his best to use his inside voice.

The reason Mark is at the clinic is to procure prescription pain medication. It turns out that he’s a regular visitor. The screenplay for The Smashing Machine (written by Safdie, who also edited the film) follows the contours of Hyams’s doc closely, dramatizing how Kerr’s career and celebrity status—and also his marriage to former Playboy model Dawn Staples (played by Emily Blunt)—were undermined by his clandestine and increasingly desperate dependence on opiates, an occupational hazard that dovetails with Johnson’s former day job working for Vince McMahon. The implication in both films is that this habit had as much to do with wounded pride as actual physical injuries. Like so many professional alpha males in the public spotlight, Kerr struggled to reconcile expressions (voluntary and not) of weakness against the self-willed myth of his own indestructibility. In one of The Smashing Machine’s funniest scenes, Mark is queried by a journalist about how he’d cope with losing an important fight. He struggles to answer the question; the thought never occurred to him. When he does lose—brutally, albeit abetted by some questionable refereeing by Japanese officials missing an illegal knee to the head—his entire conception of himself is threatened, and his response is to turn to self-abuse. He wants to prove that he can beat himself up more thoroughly than any opponent.

That The Smashing Machine is smartly made and well acted is not a surprise. Safdie’s track record as a filmmaker with his brother, Josh, is sterling stuff, comprising an empathetic rogues’ gallery of self-divided protagonists—some fictional, like Robert Pattinson’s petty hood in Good Time or Adam Sandler’s high-stakes gambler in Uncut Gems, and some authentic, like the eponymous subject of 2013’s Lenny Cooke. The latter film, which real heads recognize as one of the Safdie brothers’ best features (and a spiritual predecessor to the basketball mania of Uncut Gems) is a sobering and empathetic portrait of a high school hoops phenom who had to drastically recalibrate his expectations (and self-image) after going undrafted in 2002. There is a fine line between empathy and exploitation, and Lenny Cooke walks it so intrepidly—with such genuine curiosity about how that particular combination of hype, failure, and regret might feel—that it transcends Beyond the Glory–style clichés. The ragged multimedia mix of film and video formats alienated some critics even as it underlined the Safdie brothers’ own youthful, experimental exuberance.

The best thing about Lenny Cooke was how it felt like a collaboration—the way the Safdies managed to meet their subject on his own anxious, conflicted, and endearing terms. What’s strange about The Smashing Machine is how Safdie seems to be borrowing his terms from Hyams’s doc to the point of replicating them, sometimes shot for shot. This is not necessarily a bad thing. The Safdie brothers’ earlier films often blurred the line between fiction and documentary, and glancing, fly-on-the-wall observation is in Benny’s wheelhouse. The director and his cinematographer, Maceo Bishop, do fine work replicating the wobbly, nauseating textures of late ’90s video imagery. If Kerr’s faithfully reproduced downward spiral leaves little room for lyricism, Safdie makes the stray moments of beauty count. When Dawn gets plastered to the side of a vortex-like carnival attraction on date night—riding solo because Mark doesn’t like thrill rides—her giggling ecstasy aligns with John Secada’s 1992 soul ballad “Just Another Day,” a song whose tale of anguished devotion underscores the bad romance at the film’s center.

No less than Johnson, Blunt styles herself ably into a physical and behavioral doppelgänger for her real-life inspiration. You could superimpose her over footage of the real Dawn Staples without much confusion. The problem is that Safdie hasn’t given her much to do other than be convincing. As much as The Smashing Machine wants to be a portrait of a marriage on tilt, Dawn comes off as an afterthought. There’s a way to interpret this imbalance as reflecting Mark’s own point of view—the part of him that would just as soon have his slightly tarnished trophy wife out of sight and out of mind—but sometimes, biopic clichés are just biopic clichés. Every time Mark and Dawn begin sniping at each other, on topics ranging from his drug use to her desire to start a family, The Smashing Machine starts to resemble exactly the sort of conventional prestige-season drama that its aesthetic sensibility rejects. The intensity of the scenes is real but rote. Meanwhile, nearly every exchange between Kerr and his confidant and training partner Mark Coleman—played by former Bellator heavyweight champion Ryan Bader—rings true, to the point that it seems Safdie is focusing on the wrong pairing.

The purity of the friendship between the two Marks—and the possibility that the climactic tournament might force them to throw down despite their mutual admiration—gives The Smashing Machine some shape in the homestretch even as its fidelity to the facts guarantees an asymmetrical ending. Safdie is enough of a cinephile to recognize that the best movies about fighters—from Rocky to Raging Bull to The Wrestler—are, to some extent, meditations on failure or accounts of Pyrrhic victories, and he does his best to insert himself into that tradition. Yet it’s worth wondering what The Smashing Machine would have looked like if it had played faster and looser with the facts—if it weren’t trying to measure up to source material that already told this story comprehensively. Certainly, the Oscar buzz around Johnson’s performance will attract a mainstream audience beyond the one that saw Hyams’s doc, and Safdie’s desire to sanctify Kerr (and Coleman) as a slightly unheralded trailblazer for what has become a billion-dollar industry is honorable. What’s less clear is what The Smashing Machine accomplishes beyond being accomplished—an outcome that ultimately feels like a draw.